(PRODUCT) RED Campaign Cindy N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Actions from 2012-2016 to Begin to End the HIV/AIDS Pandemic

An Action Agenda to End AIDS EMBARGOED Critical Actions UNTIL THURSDAY, JULY 19 AT NOON ET from 2012-2016 to Begin to End the HIV/AIDS Pandemic JULY 2012 ver the last year, the conversation about the AIDS transmission. We emphasize, too, that comprehensive • Focused, Evidence-Based Prevention Programs epidemic has dramatically changed. We’re now harm reduction, decriminalization and human rights for Key Populations—to ensure that drivers of O beginning to talk about how to end it. The hope protections must be combined to effectively address the the epidemic are addressed. stems from research breakthroughs as well as an epidemics among injection drug users, men who have accumulation of evidence on the potential impact of sex with men (MSM) and sex workers around the world. To end the epidemic, we cannot do everything in “combination prevention,” which the US government Failure to implement these strategies at scale remains every setting. Nor can we look to limited AIDS has defined as including voluntary medical male a major missed opportunity of HIV prevention to date. funding to address all the many ills that undermine circumcision, the use of ART treatment in HIV-positive health and development. Core interventions people to reduce risk of transmission prevention of As the concept of combination prevention takes should be complemented, where indicated by pediatric infections and HIV testing. hold, there will inevitably be debates about which local circumstances, by other strategies, such as “America’s combination prevention strategy focuses on a interventions to prioritize. We believe the test should condom promotion, harm reduction, behavior set of interventions that have been proven most effective To begin to end the epidemic, we need to be strategic be to identify the cost-effective approaches that will best change strategies, demonstration projects for pre- — ending mother-to-child transmission, expanding and ambitious in using what is available today. -

Brand Guidelines for Partners 2019

BRAND GUIDELINES 2019 P. 2 (RED) BRAND GUIDELINES 2019 HELLO. Good to have you! (RED) is a nonprofit organization that fights AIDS. 100% of all proceeds generated from Partners go directly to The Global Fund, which distributes the money to work on the ground in Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Rwanda, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, and Zambia. We believe a strong brand keeps us inspiring and relevant, and can help you tell your story better, too. These guidelines should educate you on (RED) and equip you to message about us in the best ways possible. P. 3 (RED) BRAND GUIDELINES 2019 (RED) CONTENT OVERVIEW ABOUT FOR PARTNERS 4. Our Story 23. Partner Logos 6. Our Progress 24. Partnership Language 8. Our Partners 27. Packaging Guidelines 29. Partner Cheat Sheet THE BRAND 11. Brand Lens ASSETS + CONTACT 12. Our Logos 30. Assets 14. Registration 31. Say Hello 15. Copyright 16. Typefaces 17. Color 18. The Parentheses 19 (RED) Words 20. Language & Tone P. 4 OUR STORY (RED) was created by Bono and Bobby Shriver in 2006 to transform the collective power of consumers into a global force of critical, lifesaving aid. (RED) BRAND GUIDELINES 2019 We work with the world’s most iconic brands— including Apple, Starbucks, Belvedere Vodka, Bank of America, and more—to develop (PRODUCT)RED branded products and experiences that, when purchased, trigger corporate giving to the Global Fund. With these contributions, the Global Fund finances programs in sub-Saharan Africa, which provide HIV+ pregnant women access to the lifesaving medication they need to ensure their babies are born HIV-free. -

Abstract Supplement

ONLINE ONLINE OPEN PEER-REVIEWD PEER-REVIEWD ONLINE A PEER-REVIEWD OPEN ACCESS OPEN HIV/AIDS JOURNAL HIV/AIDS JOURNAL CCESS ONLINEONLINE CCESS A OPEN OPEN PEER-REVIEWD ONLINE HIV/AIDS JOURNAL HIV/AIDS HIV/AIDS JOURNAL PEER-REVIEWD PEER-REVIEWD OPEN ACCESSONLINEPEER-REVIEWD A ONLINEPEER-REVIEWD CCESS HIV/AIDS JOURNALPEER-REVIEWD OPEN ACCESS CCESS A OPEN ONLINE ONLINE HIV/AIDS JOURNAL ONLINE PEER-REVIEWDHIV/AIDS JOURNALONLINEONLINE PEER-REVIEWDOPEN ACCESS PEER-REVIEWD ONLINE ONLINE OPEN ACCESSONLINE OPEN HIV/AIDS JOURNAL CCESS OPEN ACCESS HIV/AIDS JOURNAL PEER-REVIEWD PEER-REVIEWD PEER-REVIEWD HIV/AIDS JOURNAL PEER-REVIEWD A HIV/AIDS JOURNAL OPEN ACCESS PEER-REVIEWD PEER-REVIEWD PEER-REVIEWDONLINE HIV/AIDS JOURNAL HIV/AIDS JOURNAL OPEN ACCESS ONLINE ONLINEONLINE HIV/AIDS JOURNAL HIV/AIDS PEER-REVIEWD A PEER-REVIEWD ONLINE ONLINE HIV/AIDS JOURNAL CCESS HIV/AIDS JOURNALOPEN ONLINE PEER-REVIEWDONLINE PEER-REVIEWD HIV/AIDS JOURNAL OPEN PEER-REVIEWDJOURNAL HIV/AIDS HIV/AIDS JOURNAL HIV/AIDS JOURNAL CCESS ONLINE A A ONLINE OPEN ACCESS HIV/AIDS JOURNAL ONLINE HIV/AIDS JOURNAL CCESS PEER-REVIEWD OPEN ACCESS HIV/AIDS JOURNAL OPEN ACCESS ONLINE HIV/AIDS JOURNAL HIV/AIDS ONLINE OPEN OPEN ACCESS HIV/AIDS JOURNAL PEER-REVIEWD OPEN HIV/AIDS JOURNALPEER-REVIEWD PEER-REVIEWD OPEN ACCESS PEER-REVIEWD CCESS A OPEN PEER-REVIEWDONLINE PEER-REVIEWD PEER-REVIEWD HIV/AIDS JOURNALAbstractHIV/AIDS JOURNAL SupplementHIV/AIDS JOURNAL PEER-REVIEWD OPEN ACCESS CCESS PEER-REVIEWD A PEER-REVIEWD Oral abstracts of the 21st International AIDS Conference A CCESS OPEN ACCESS -

UNAIDS/WHO (2008) Report on the Global HIV/AIDS Epidemic

Report on the 08 global AIDS epidemic Executive summary UNAIDS/08.27E / JC1511E (English original, July 2008) © Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2008. All rights reserved. Publications produced by UNAIDS can be obtained from the UNAIDS Content Management Team. Requests for permission to reproduce or translate UNAIDS publications—whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution—should also be addressed to the Content Management Team at the address below, or by fax, at +41 22 791 4187, or e-mail: [email protected]. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNAIDS concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specifi c companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by UNAIDS in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. UNAIDS does not warrant that the information contained in this publication is complete and correct and shall not be liable for any damages incurred as a result of its use. Cover photo: UNAIDS / N. Lieber WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic 2008: executive summary. “UNAIDS/08.27E / JC1511E”. 1.HIV infections − epidemiology. 2.HIV infections − therapy. 3.Acquired immunodefi ciency syndrome − epidemiology. 4.Acquired immunodefi ciency syndrome − prevention and control. -

Better (Red)™ Than Dead? Celebrities, Consumption and International Aid Richey, Lisa Ann; Ponte, Stefano

Better (Red)™ Than Dead? Celebrities, Consumption and International Aid Richey, Lisa Ann; Ponte, Stefano Document Version Accepted author manuscript Published in: Third World Quarterly DOI: 10.1080/01436590802052649 10.1080/01436590802052649 Publication date: 2008 License Unspecified Citation for published version (APA): Richey, L. A., & Ponte, S. (2008). Better (Red)™ Than Dead? Celebrities, Consumption and International Aid. Third World Quarterly, 29(4), 711-729. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590802052649, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590802052649 Link to publication in CBS Research Portal General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us ([email protected]) providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Post-print of Richey, L. A. and Ponte, S. (2008) “Better REDTM than Dead? Celebrities, Consumption and International Aid”, Third World Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 711-729. DOI: 10.1080/01436590802052649 Stable URL to publisher: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01436590802052649#.VCp9Fi5_sgE BETTER (RED)™ THAN DEAD? CELEBRITIES, CONSUMPTION AND INTERNATIONAL AID Introduction Bono’s launch of Product (RED)TM at Davos in 2006 opens a new frontier for development aid. Product RED is ‘a brand created to raise awareness and money for The Global Fund by teaming up with iconic brands to produce RED-branded products’.1 Consumption, trade, and aid wed dying Africans with designer goods. -

Macrophages Provide a Transient Muscle Stem Cell Niche Via NAMPT Secretion

Article Macrophages provide a transient muscle stem cell niche via NAMPT secretion https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03199-7 Dhanushika Ratnayake1,2, Phong D. Nguyen3,4,11, Fernando J. Rossello1,5,11, Verena C. Wimmer6,7,11, Jean L. Tan1,2,11, Laura A. Galvis1,9, Ziad Julier1,2, Alasdair J. Wood1,2, Received: 20 June 2019 Thomas Boudier6,7, Abdulsalam I. Isiaku1, Silke Berger1,2, Viola Oorschot8,10, Accepted: 7 January 2021 Carmen Sonntag1,2, Kelly L. Rogers6,7, Christophe Marcelle1,9, Graham J. Lieschke1, Mikaël M. Martino1,2,12, Jeroen Bakkers3,4,12 .& Peter D Currie1,2 ✉ Published online: xx xx xxxx Check for updates Skeletal muscle regenerates through the activation of resident stem cells. Termed satellite cells, these normally quiescent cells are induced to proliferate by wound-derived signals1. Identifying the source and nature of these cues has been hampered by an inability to visualize the complex cell interactions that occur within the wound. Here we use muscle injury models in zebrafsh to systematically capture the interactions between satellite cells and the innate immune system after injury, in real time, throughout the repair process. This analysis revealed that a specifc subset of macrophages ‘dwell’ within the injury, establishing a transient but obligate niche for stem cell proliferation. Single-cell profling identifed proliferative signals that are secreted by dwelling macrophages, which include the cytokine nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (Nampt, which is also known as visfatin or PBEF in humans). Nampt secretion from the macrophage niche is required for muscle regeneration, acting through the C-C motif chemokine receptor type 5 (Ccr5), which is expressed on muscle stem cells. -

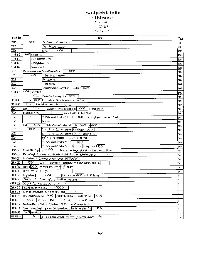

DBA Inteliigence Publications Titles with Fol Exemptions Second

DBA IntelIigence Publications Titles with FOl Exemptions Second Section 1997 - 2015 As of july 25. 2015 Prod- No. Title Year 01005 (b)(7')(A) Coca Cultivation & Cocaine Base Production 2001 01015 Cultivio de Coca y Producción 2001 studies in (b)(7)(A) | 02036 2002 NPMP-142 (b)(7)(A) Marijuana Routes 2003 NPMP-142 Money Laundering Routes 2003 NPMP-142 Methamphetamine Routes 2003 NPMP-142 Pharmaceutical Routes 2003 04039 Methamphetamine and Chemical Diverson Situation! (b)7)(A) | 2004 05007 (b)(7)(A) Technical Notes, First Edition 2005 05019 |(b)(7 )Coca Yields 2005 06002 Technical Motes 2006 06019 Opium Poppy Cultivation and Heroin Production inf (b)(7)(A) 2006 NPMP-102 (b)(7)(A) | Cocaine Routes 2006 (b)(7)(A) | Cocaine Base Processing m the| (b)(7)(A) | 07022 2007 DIB-004-07 |an^ (b)(7)(A) Traffickers Expand Ties in the Methamphetamine Trade 2007 DIB-005-07 (b)(7)(A) The New Front Line in the Battle for the Border 2007 Jo t (b)(7)(A) |5tudy to Estimate Coca Leaf Yields in the| (b)(r)(A) Region of (b)(7)(A) 08014 in 2008 08024 Drug Related Deaths (b)(''HA) |Aiea of Responsibility (Unclassified) 2008 08027 (b)(7)(A) Studies to Estimate Coca Leaf Yields in the (b)(7)(A) Growing Regions of Arauca and Vichada 2008 08029 Dictionary 2008 Joint (b)(7)(A) Study to Estimate Coca Leaf Yields in he (b)(7)(A) of (b)(7)(A) 08041 t 2008 09005 (b)( 7 )(A) Study to Estimate Coca Leaf YieIds i n the (b)(7)( | Regio ns of (b)(7)(A) ] 2009 09010 Study to Estimate Coca Leaf Yields in the) (b)(7)(A) |Regian of| (b)(7)(A) | 2009 09014 (b)(7) |Heroin Assessment -

Lost AIDS: Luc Montagnier's

Friday, June 18, 2010 Home Get Audio/Vide The Board Contact Us Q&A Languages Donate to RA About Involved! o Part I · Part II · Part III · Part IV NoName TV interviews RA board member Dr. Etienne de Harven and Jean-Claude Roussez, authors of "Ten Lies about AIDS" An Interview with Tommy Morrison Former World Boxing Organization Champion February 10, 2010 — On top of the world in 1996, heavyweight boxing champion, star of Rocky V with Sylvester Stallone, winner of almost every fight, his life was turned upside down when he tested positive for HIV antibodies just before a fight. In 2006 he re-tested negative and has tested negative many times since. In an interview with Celia Farber, RA president David Crowe and Terry Michael, Morrison states: "HIV doesn't hurt anybody...It's a passenger virus, it doesn't do anything...I thought the medication was what was killing people." Listen to the entire interview at HowPositiveAreYou.com: Recently, another renowned athlete, Olympic Gold Medalist Lee Evans, spoke of AIDS and Africa, expressing his doubts about widely accepted beliefs: "I have been all over Africa for almost 30 years and when I first heard there was a new sexually transmitted disease epidemic I was alarmed...All I ever saw was more and more of the same diseases we saw in 1975...but nobody except the media and the people living off AIDS money ever called that AIDS." Djamel Tahi January, 2010 Speak out, Monsieur le Professeur Montagnier! A few days ago, a video clip was posted on the Internet, which produced the kind of buzz that is shaking the world of AIDS research. -

A Biopolitical and Rhetorical Mosaic of HIV Stigma in a Time of Prep-Aration

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2017 Governmentality/Animacy/Mythology: A Biopolitical and Rhetorical Mosaic of HIV Stigma in a Time of PrEP-aration Brendan Geoffrey Aaron Hughes University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons, and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hughes, Brendan Geoffrey Aaron, "Governmentality/Animacy/Mythology: A Biopolitical and Rhetorical Mosaic of HIV Stigma in a Time of PrEP-aration" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1352. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1352 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Governmentality/Animacy/Mythology: A Biopolitical and Rhetorical Mosaic of HIV Stigma in a Time of PrEP-aration __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Brendan G.A. Hughes August 2017 Advisor: Dr. Christina R. Foust, PhD ©Copyright by Brendan G.A. Hughes 2017 All Rights Reserved Author: Brendan G.A. Hughes Title: Governmentality/Animacy/Mythology: A Biopolitical and Rhetorical Mosaic of HIV Stigma in a Time of PrEP-aration Advisor: Dr. Christina R. Foust, PhD Degree Date: August 2017 Abstract Since 1981, roughly 35 million people have died from the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), the end stages of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), and an estimated 39 million are living with HIV today. -

Philanthropic Support to Address Hiv/Aids in 2015 Our Mission

PHILANTHROPIC SUPPORT TO ADDRESS HIV/AIDS IN 2015 OUR MISSION The mission of Funders Concerned About AIDS (FCAA) is to mobilize the leadership, ideas, and resources of funders to eradicate the global HIV/AIDS pandemic and to address its social and economic dimensions. FCAA envisions a world without AIDS, facilitated by a philanthropic sector that works collaboratively, transparently, and urgently to ensure focused and robust funding for: Evidence-based interventions in the treatment and prevention of HIV infection; Advocacy, research, and exploration of new methods to hasten the end of AIDS; and, Investments that address the social inequities, health disparities, and human rights abuses that fueled the spread of the epidemic. FCAA BOARD OF DIRECTORS J. Channing Wickham Lisa Bohmer Gregorio Millett Chair Conrad N. Hilton Foundation amfAR, The Foundation Washington AIDS Partnership for AIDS Research Andrea Flynn Alice Lin Fabiano M•A•C AIDS Fund Kathy Palumbo Vice Chair The Community Foundation Julia Greenberg Johnson & Johnson for Greater Atlanta Open Society Foundations John Edmiston Shari Turitz Shane Jenkins Secretary American Jewish World Service Magic Johnson Foundation Kaiser Permanente Louise van Deth Michael N. Joyner Daniel Jae-Won Lee Aids Fonds/STOP AIDS NOW! ViiV Healthcare Treasurer Korab Zuka Levi Strauss Foundation Brook Kelly-Green Gilead Sciences Ford Foundation FCAA STAFF John L. Barnes Sarah Hamilton Caterina Gironda Executive Director Director of Operations Research & Communications Associate THANK YOU FCAA wishes to thank Broadway Erika Baehr, primary author private philanthropic funders engaged Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, Open Society in HIV/AIDS in Southern Africa, as well The FCAA Resource Tracking Advisory Foundations, and the Ford Foundation as all those funding organizations that Committee: Alicia Carbaugh, The for their generous funding of this participated. -

The Fourth Wave Violence, Gender, Culture & HIV in The

The Fourth Wave Violence, Gender, Culture & HIV in the 21st Century The Fourth Wave Violence, Gender, Culture & HIV in the 21st Century editors Jennifer F. Klot and Vinh-Kim Nguyen series editors Saniye Gülser Corat and Lydia Ruprecht A publication developed in the context of a project led by the UNESCO Division for Gender Equality of the Bureau of Strategic Planning in collaboration with the Division for Cultural Policies and Intercultural Dialogue of the Culture Sector. © 2009 UNESCO All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. Published by UNESCO The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNESCO and its Member States. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The fourth wave : violence, gender, culture, and HIV in the 21st century / edited by Jennifer F. Klot and Vinh-Kim Nguyen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-9841257-1-5 1. AIDS (Disease)—Social aspects. 2. Sex customs. 3. Sexual abuse victims. I. Klot, Jennifer F. II. Nguyen, Vinh-Kim. RC606.6.F68 2009 362.196’9792—dc22 2009040366 Contents foreword 11 Saniye Gülser Corat and Lydia Ruprecht introduction 15 Jennifer F. Klot and Vinh-Kim Nguyen section i: the new geography of hiv introductory essay 29 Veena Das chapter 1 37 Globalization and gendered vulnerabilities to HIV and AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa Colleen O’Manique chapter 2 53 Social exclusion: The gendering of adolescent HIV risk in South Africa Kelly K. -

Celebrity Power: Spotlighting and Persuasion in the Media

Celebrity Power: Spotlighting and Persuasion in the Media BY ©2014 Mark Harvey Submitted to the graduate degree program in Political Science and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Committee: ____________________________________ Chairperson Mark R. Joslyn ____________________________________ Donald P. Haider-Markel ____________________________________ Burdett A. Loomis ____________________________________ John J. Kennedy ____________________________________ James F. Daugherty Defended April 1, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Mark Harvey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Celebrity Power: Spotlighting and Persuasion in the Media ____________________________________ Chairperson Mark R. Joslyn Date Approved: April 1, 2014 ii Abstract As technological and business demands have transformed the operation and demands on news and entertainment media, celebrity activists have proliferated. Only a few years ago, the notion that these celebrities were anything other than opportunistic was laughable. Less likely was the prospect that celebrities might have real power to change minds or affect outcomes. It is difficult enough for politicians to set public agendas. Can celebrities compete? This dissertation compares celebrities to politicians and focuses upon one key area of potential power: media agenda setting. If celebrities hope to change the public agenda to focus on the issues they think are important, can they gain attention for those issues and are they persuasive? The results of a time series analysis and an experimental study conclude that they are capable of not only competing with politicians in “spotlighting” and persuasion on political issues, but may at times, exceed their abilities. These findings potentially upend what many political scientists assume about power, particularly scholars who study policymaking, policy entrepreneurship, and social movements.