Arxiv:1801.09253V1 [Cond-Mat.Soft] 28 Jan 2018 Eral Basic Viscoelastic Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Accidental Discoveries

Accidental discoveries Part of the British Science Association’s British Science Week activity pack series. www.britishscienceweek.org British Science British British Science www.britishscienceweek.org 0 Accidental discoveries: Bakelite plastic Making silly putty More than one hundred years ago, electric wires were covered with ‘shellac’. It stopped people getting an electric shock if they touched the wire. It was very expensive because it was made from beetles that came from Asia. So, a man called Leo Baekeland decided to make a new type of covering. However, instead he discovered how to make the first plastic, called Bakelite. Plastics can be moulded into all kinds of shapes. They are used to make all sorts of things. You can have a go at making a bouncy plastic, called silly putty. You will need: 2 containers (such as plastic cups), a wooden stick (for This 1950s telephone is made from Bakelite stirring), some food colouring, PVA glue, borax solution (about 1 tablespoon of borax to a cup of water) What you do Put about one tablespoon of borax into one cup of water. Stir until it dissolves. Stir in two or three drops of food colouring. Put some PVA glue into the other container – just enough to cover the bottom. Pour some of the borax solution into the PVA glue. Stir the mixture until it makes a soft lump. By now the mixture should be joining together like putty. Take it out of the container and mould it into a ball in your hands. If it is still sticky, wash your hands with water and rinse the ball. -

Understanding Silly Putty, Snail Slime and Other Funny Fluids

IMA Annual Program Year Tutorial An Introduction to Funny (Complex) Fluids: Rheology, Modeling and Theorems September 12-13, 2009 Understanding silly putty, snail slime and other funny fluids Chris Macosko Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science NSF- MRSEC (National Science Foundation sponsored Materials Research Science and Engineering Center) IPRIME (Industrial Partnership for Research in Interfacial and Materials Engineering) What is rheology? ρειν (Greek) = to flow τα παντα ρει = every thing flows rheology = study of flow?, i.e. fluid mechanics? honey and mayonnaise honey and mayo stress= viscosity = f/area stress/rate rate of deformation rate of deformation What is rheology? ρειν (Greek) = to flow τα παντα ρει = every thing flows rheology = study of flow?, i.e. fluid mechanics? honey and mayo rubber band and silly putty viscosity modulus = f/area rate of deformation time of deformation 4 key rheological phenomena rheology = study of deformation of complex materials fluid mechanician: simple fluids complex flows materials chemist: complex fluids complex flows rheologist: complex fluids simple flows rheologist fits data to constitutive equations which - can be solved by fluid mechanician for complex flows - have a microstructural basis from: Rheology: Principles, Measurement and Applications, VCH/Wiley (1994). ad majorem Dei gloriam Goal: Understand Principles of Rheology: (stress, strain, constitutive equations) stress = f (deformation, time) Simplest constitutive relations: Newton’s Law: Hooke’s Law: dγ τ = η = ηγ τ = Gγ dt Key Rheological Phenomena • shear thinning (thickening) h ( g ) • time dependent modulus G(t) • normal stresses in shear N1 η η • extensional > shear stress u > k k 1 ELASTIC SOLID 1 2 The power of any spring L´ is in the same proportion with the tension thereof. -

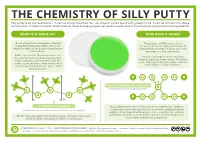

THE CHEMISTRY of SILLY PUTTY Silly Putty Is an Odd Substance – It Can Be Slowly Stretched Out, but Snaps If Pulled Apart with Greater Force

THE CHEMISTRY OF SILLY PUTTY Silly putty is an odd substance – it can be slowly stretched out, but snaps if pulled apart with greater force. It can be molded into shape, but bounces if rolled into a ball. What’s behind these strange properties? Here’s a quick look at the chemical composition and explanation. WHAT IS IT MADE OF? HOW DOES IT WORK? The most important compound in silly putty The presence of PDMS alone, and its is polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS). This is the viscoelasticity, doesn’t fully explain how silly simplest member of the polymer family known putty behaves. Another ingredient, boric acid, as the silicones. also makes a telling contribution. PDMS is viscoelastic. This means that it acts The boric acid helps to create ‘crosslinks’ like a viscous liquid and flows over long time between adjacent polymer chains. These help scales. However, over short time scales (for to give silly putty its putty-like nature, and also example, being rolled into a ball and thrown at help explain its strange behaviour. a hard surface), its behaviour is elastic, and it will bounce back. R Si O O Si R – EXAMPLE BORON-MEDIATED CROSSLINK B Si Si Si (R represents the rest of the PDMS polymer chain) O O R Si O O Si R n A POLYDIMETHYLSILOXANE The polydimethylsiloxanes in silly putty end in Si-OH groups. The boric (solid filled atoms represent carbon; smaller outlined atoms represent hydrogen) acid reversibly reacts with these to form short-lived crosslinks between polymer chains. Slow deformation gives these crosslinks time to break and reform, allowing viscous flow, but rapid, forceful deformation does At high molecular weights, the flexible polymer chains become loosely not, so elastic behaviour is instead seen. -

Fourteen K-12 Outreach Activities for Materials Scientists and Engineers

FOURTEEN K-12 OUTREACH ACTIVITIES FOR MATERIALS SCIENTISTS AND ENGINEERS Foreward The activities described in this document were performed by volunteers from ASM International chapters as part of our volunteer leader training in 2007. The event took place in an elegant room with carpet, drapes, and wallpaper so heat treating was done in advance. A similar approach could be used to make the “heat treating” activities safe for younger students. Please take the utmost care to consider safety aspects as you plan your outreach event. Safety glasses that fit over corrective lenses are needed for many of these activities, and you may have trouble finding them small enough to fit young students. Many of the activities were gleaned from the ASM Materials Education Foundation’s “Teachers Camp” curriculum and have been proven in classrooms. I’m particularly grateful to Debbie Goodwin (Master Teacher) and Matt Perricone for their contributions to this compilation, and to Dr. Kathy Hayrynen of the Detroit Chapter of ASM International for her ongoing contributions to ASM’s outreach projects at many levels. All of the experimental descriptions in this compilation are either free of copyright protection, or have been used in accordance with the use restrictions of the original source. Original sources for each activity have been noted in the appendices. Commercial sources for some supplies have been mentioned as a convenience, and are not an endorsement of the particular company by ASM International, The ASM Foundation, or me. I hope you’ll have as much fun sharing our profession with students and teachers as I do. -

Gak and Non-Newtonian Fluid

1) A polymer consists of long chained molecules that are bound together. 2) Non-Newtonian fluids are those that have viscosities that change with conditions of stress or time. Background Gak – Glue consists of long chained molecules that are very loosely tied together, which explains why it has a higher viscosity than water. When mixed with Borax, the molecules are “tangled” and a chemical reaction takes place. The tangled chains are polymers which is what plastics are and other man made substances such as nylon. http://www.petervaldivia.com/technology/plastics/i mage/polymer.gif&imgrefurl=http://www.peterval divia.com/technology/plastics/index A Non-Newtonian fluid is one that is not characterized by one viscosity. Such fluids have viscosities that change as a function of stress, time or both. A mixture of cornstarch and water flows when little stress is applied, yet acts like a solid when a lot of stress is applied – for example, hitting the surface with your hand or even jumping quickly on it. Uses of such fluids may be in body armor. There are other non-Newtonian fluids that have the opposite reaction to stress. Fluids such as ketchup become less viscous when stress is applied (hence hitting the bottle of ketchup allows the ketchup to flow out). Cornstarch and water mixture Cornstarch and water mixture on a speaker http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/common s/f/f0/Non-Newtonian_fluid.PNG Materials Demonstration – polymers Gak (per group) Various plastic containers. Dixie cup for mixing Wooden stirrer Small plastic ziplock bag for storing Demonstration – Viscosity Borax/water mixture Glue/water mixture Plastic board Food Coloring if desired Various liquids of different viscosity to drip on slanted board and watch run them run off Non Newtonian fluid (per group) Ketchup in a glass bottle Dixie cup for mixing Wooden stirrer Demonstration – Pool of Small plastic ziplock bag for storing Cornstarch/water Cornstarch Water Kiddie pool of cornstarch/water. -

Groomstick: a Study to Determine Its Potential to Deposit Residues Author(S): Sara A

Article: Groomstick: A study to determine its potential to deposit residues Author(s): Sara A. Moy Source: Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Eleven, 2004 Pages: 29-42 Compilers: Virginia Greene and Patricia Griffin th © 2007 by The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works, 1156 15 Street NW, Suite 320, Washington, DC 20005. (202) 452-9545 www.conservation-us.org Under a licensing agreement, individual authors retain copyright to their work and extend publications rights to the American Institute for Conservation. Objects Specialty Group Postprints is published annually by the Objects Specialty Group (OSG) of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works (AIC). A membership benefit of the Objects Specialty Group, Objects Specialty Group Postprints is mainly comprised of papers presented at OSG sessions at AIC Annual Meetings and is intended to inform and educate conservation-related disciplines. Papers presented in Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Eleven, 2004 have been edited for clarity and content but have not undergone a formal process of peer review. This publication is primarily intended for the members of the Objects Specialty Group of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works. Responsibility for the methods and materials described herein rests solely with the authors, whose articles should not be considered official statements of the OSG or the AIC. The OSG is an approved division of the AIC but does not necessarily represent the AIC policy or opinions. AIC Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume 11, 2004 GROOMSTICK: A STUDY TO DETERMINE ITS POTENTIAL TO DEPOSIT RESIDUES Sara A. Moy Abstract The use of kneadable eraser products for dry surface cleaning on works of art is a common practice adopted from paper and book conservation, but questions as to their suitability consistently arise with the availability of each new product. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2014/0261026 A1 Mcclure Et Al

US 20140261026A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2014/0261026 A1 McClure et al. (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 18, 2014 (54) COMPOSITIONS AND METHODS FOR (52) U.S. Cl. MAKING PUTTY TRANSFER BOOKS CPC ..................................... B4IM 5/025 (2013.01) USPC ............................................. 101/35; 101/492 (71) Applicant: CRAYOLA LLC, Easton, PA (US) (57) ABSTRACT (72) Inventors: David McClure, Roanoke, VA (US); The present invention provides kits and methods for selec Keith Ketchman Rosemont IL (US); tively transferringaportion of an image from a substrate (e.g., Michael Craig Sciota, PA (US) s paper) to a dough (e.g., Silly Putty R) comprising pressing the s s dough onto an image printed on the Substrate. The image comprises transferable ink and non-transferable ink. At least (73) Assignee: Crayola LLC, Easton, PA (US) a portion of the image comprising transferable ink transfers from the substrate to the dough and the non-transferable ink (21) Appl. No.: 13/800,780 does not transfer from the substrate to the dough. The dough can be used to reveal an image that was “hidden within the (22) Filed: Mar 13, 2013 visible image printed on the substrate. The present invention also provides methods for making a Substrate with an image Publication Classification comprising transferable ink (e.g., cold-set web ink) and non transferable ink (e.g., sheet-fed offset ink) printed thereon, (51) Int. Cl. comprising using a sheet-fed offset press to print the image B4LM 5/025 (2006.01) onto the substrate. US 2014/0261026 A1 Sep. 18, 2014 COMPOSITIONS AND METHODS FOR substrate to the dough. -

Silly Science (Target Audience: Ages 9–12)

Silly Science (Target Audience: Ages 9–12) Recommended Silly Science Books You do not need these books to do this program. Any fun science experiment books will do. You can use them for display, to promote the science experiments collection, and for the kids to check out. Or you can use them to get other ideas for science program activities. Bill Nye the Science Guy’s Consider the Following: A Way Cool Set of Science Questions, Answers and Ideas to Ponder by Bill Nye Science Fun: Hands-on Science with Dr. Zed by Gordon Penrose First Science Experiments: The Amazing Human Body by Shar Levine and Leslie Johnstone Really Rotten Experiments by Nick Arnold Silly Science Tricks by Peter Murray Silly Science: Strange and Startling Projects to Amaze Your Family and Friends by Shar Levine and Leslie Johnstone Science Experiments You can choose one or more of the following activities for your program (approximate times for each activity are given so you can plan accordingly). Experiment #1: Make Gooey Slime and Play Putty (Similar To Silly Putty®) Have lots of fun doing this science project. Talk about slime in children’s films and books – even Harry Potter. The polymers we make here are non-toxic; however, eating the stuff is definitely not recommended! Time: 30 minutes Materials: • White glue (Elmer’s white glue preferred here) • Borax (a laundry booster available at the supermarket) • Water • Sealable plastic bags • Popsicle sticks or disposable spoons (unused and clean) • Large jar and lid (clean) • Medium-sized bowl 128 • Food colouring • Measuring cup • Sheets of newspaper to keep your work area clean • Paper towels for cleaning up Directions: 1. -

Silly Putty Lab Chemistry

Name: _____________________________________ Partner____________________________________ Silly Putty Lab Chemistry: Elmer’s Glue is made up of polyvinyl acetate. The borax molecules react with glue molecules (relatively long polymer chains) to form new bonds between one borax and two glue molecules. The linking of two glue molecules via one borax molecule is called polymer cross-linking and it makes a bigger polymer molecule, which is now less liquid-like and more solid. The silly putty is held together by very weak intermolecular bonds that provide flexibility around the bond and rotation about the chain of the cross-linked polymer Directions: 1. Wear goggles. 2. Add one cup of glue and one cup of water to empty, clean plastic milk jug. 3. Mix thoroughly with popsicle stick. 4. Add 2-3 drops of food coloring. 5. Mix thoroughly with popsicle stick. 6. Add one cup of borax solution. 7. Mix thoroughly with popsicle stick. 8. Take silly putty out of jug and knead with hands Observations: 1. Observations of pulling the silly putty slowly: 2. Observations of pulling the silly putty quickly: Questions: 1. How do the physical properties of the glue/water mixture change as a result of adding the borax solution? 2. What would be the effect (your thoughts) of adding more borate solution? 3. Press the silly putty against your hand. Describe what happens. Don’t forget to clean up and wash your hands! 4. Try to roll the silly putty into a ball on the table. Describe what happens. 5. Stretch the silly putty slowly. How long can you stretch it? (cm) 6. -

The Cambridge Polymer Group Silly Putty™ “Egg” Silly Putty™ Is a Registered Trademark of Binney and Smith

CPGAN #026 Characterization of Silly Putty ©Cambridge Polymer Group, Inc. (2014). All rights reserved The Cambridge Polymer Group Silly Putty™ “Egg” Silly Putty™ is a registered trademark of Binney and Smith Introduction Silly Putty™ is a material that vividly demonstrates the richness and complexity of behavior that apparently simple materials can produce. When first handled, the initial impression given by Silly Putty™ is that of a plastic material. It can be easily kneaded, much like dough, into any shape desired. On short time scales these complex shapes appear to be permanent distortions of the material. However, upon longer inspection the material is seen to sag under its own weight although the putty does not flow indefinitely on a flat surface. If rolled into a ball and dropped, the material bounces like an elastic material. In addition, if a shock or impulsive load is applied to the putty, it will shatter. The behavior of this fascinating material gives insight into the rheological behavior of many materials. In rheological terms the experimenter is distorting the Silly Putty™ over a range of Deborah numbers. This non-dimensional parameter describes the ratio of the fluid relaxation time scale to that of the experimental time scale. A high Deborah number therefore corresponds to a fast experiment in which the load or impulse is applied over a very short time scale. Composition Silly Putty™ is a silicone material produced by Dow Corning® Corporation (under the name of Dow Corning® 3179 Dilatant Compound). According to Dow Corning the composition (by weight percentage) is as outlined in the table below. -

Non-Newtonian Fluids How Slow Can You Go?

Student Name: ____________________________ Date: ____________ Non-Newtonian Fluids How slow can you go? Background Have you heard of Sir Isaac Newton? Newton (1643-1727) is a famous scientist and mathematician who discovered gravity! In addition, he created the three laws of motion, contributed to creating calculus and predicted the shape of the earth. Newton also did a lot of work with fluids. Newton described how “normal” fluids, like water, behave. For example, these fluids have a constant viscosity. For Newtonian fluids (or “normal” fluids), viscosity only changes with temperature. Viscosity refers to a fluid’s resistance to flow. A highly viscous substance flows slowly. For example, peanut butter is more viscous than water because it is more difficult to pour. There are some fluids that do not have a constant viscosity, and these are called non-Newtonian fluids. These fluids can be affected by other factors besides temperature, such as stress. Applying -

Crosslinked Polymers Based on Polyborosiloxanes: Synthesis and Properties

Journal of Organometallic Chemistry 891 (2019) 72e77 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Organometallic Chemistry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jorganchem Crosslinked polymers based on polyborosiloxanes: Synthesis and properties * Fedor V. Drozdov a, , Sergey A. Milenin a, Vadim V. Gorodov a, Nina V. Demchenko a, Michail I. Buzin b, Aziz M. Muzafarov a, b a N.S. Enikolopov Institute of Synthetic Polymer Materials, Russian Academy of Sciences, 117393, Moscow, Russian Federation b A.N. Nesmeyanov Institute of Organic Element Compounds, Russian Academy of Sciences, 119991, Moscow, Russian Federation article info abstract Article history: In current work, crosslinked polyborosiloxanes (PBS) were synthesized by the Piers-Rubinsztajn reaction Received 13 February 2019 based on polydimethylsiloxanes (PDMS) with terminal dimethylhydrosilyl or distributed methylhy- Received in revised form drosilyl groups in the polymer chain and boronic or phenyl boronic acid methyl esters. Depending on the 9 April 2019 number and location of the methylhydrosilyl groups in the initial PDMS, as well as on the functionality of Accepted 18 April 2019 the boronic component (2 for phenyl boronic and 3 for boronic acid methyl esters), PBS with different Available online 20 April 2019 macromolecular architecture and crosslinking density were obtained. PBS based on PDMS with terminal dimethylhydrosilyl groups, crosslinked with trimethyl borate, are soluble in common solvents such as THF, toluene and chloroform, whereas PBS based on PDMS with distributed methylhydrosilyl groups are non-soluble. Investigations in an environmental chamber showed hydrolytic stability of the PBS samples under experimental conditions, which was confirmed by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) and infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). In the investigations of thermal stability of obtained PBS, 5% weight loss was observed at 380e430 C.