Why Tensions in the South Caucasus Remain Unresolved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best of Belarus and the Baltics in 11 Days

THE BEST OF BELARUS AND THE BaLTICS IN 11 DAYS ALL TOURS WITH GUARANTEED www.baltictours.com DEPARTURE! 1 TRAVEL SPECIALISTS Vilnius, Lithuania SINCE 1991 Baltic Tours has been among the ranks of the best for 27 years! Since 2007 Baltic Tours in collaboration with well experienced tourism partners have guaranteed departure tour services offering for over 30 tour programs and more than 300 guaranteed departures per year. Our team believes in the beauty of traveling, in the vibe of adventure and the pleasure of gastronomy. Traveling is a pure happiness - it has become our way of living! I have a degree in tourism management and I encourage our guests to explore the Northeastern region of Europe in its most attractive way. I’ve been working in tourism industry since 2013 and I’m assisting customers from 64 countries. Take a look at my personally selected tours and grab your best deal now! SERVICE STANDARDS MORE VALUE GUARANTEED ESCORTED TOURS QUALITY, SAFETY AND SECURITY SPECIAL FEATURES PRE- AND POST- STAYS www.baltictours.com 3 Kadriorg Park, Tallinn, Estonia JUNE-August, 2021 INCLUDING 11 days/10 nights THE BEST OF TALLINN ● ESTONIA 10 overnight stays at centrally located 4* GBE11: 03 Jun - 13 Jun, 2021 BELARUS AND hotels GBE15: 01 Jul - 11 Jul, 2021 10 x buffet breakfast GBE19: 29 Jul - 08 Aug, 2021 RIGA LATVIA Welcome meeting with champagne-cocktail GBE21: 12 Aug - 22 Aug, 2021 or juice THE BALTICS Personalised welcome package LITHUANIA Entrances to Peter and Paul Church in Vilnius, Rundale Palace and medieval Great Guild IN 11 DAYS VILNIUS Hall in Tallinn MINSK Service of bilingual English-German speaking tour leader on all tours BELARUS Service of 1st class buses or 1st class minivans throughout the itinerary Train tickets Minsk-Vilnius, 2nd class, OW Portage at hotels -Charlotte- National Library of Belarus, Minsk, Belarus “First of all, I would like to say a lot of good words for Rasa. -

LISTING Armenia Securities Exchange

Armenia Securities Exchange Monthly Bulletin | March 2019 See Inside For: Securities Listed and Delisted in March, 2019 Equities Market Financial Highlights of the Issuers Listed on Armenia Securities Exchange Corporate & Government Bonds Market REPO/SWAP Market Overview of Depository Activities LISTING As of March, 2019, 83 securities of 23 issuers were listed and admitted to trading at Armenia Securities Exchange: 10 stocks of 10 issuers and 73 bonds of 16 issuers. Please find below information about securities, listed and/or admitted to trading during this month. List / Free Number of Date listed/ N Ticker Company Nominal value Market securities issued admitted to trading 1 Bbond FNCAB4 FINCA UCO CJSC 80,000 USD25 18.03.2019 2 Abond ANLBB7 IDBank CJSC 50,000 USD100 27.03.2019 In February, 2019 the following securities were redemed from trading at Armenia Securities Exchange. Number of N List Stock symbol Company Nominal value Termination Date securities issued 1 Abond ANLBB3 IDBank CJSC 50,000 AMD20,000 15.03.2019 1 amx.am EXCHANGE TRADING All financial figures are in Armenian Drams (AMD) unless otherwise noted. Exchange rates established by the Central Bank of Armenia as of March, 2019 were as follows: USD - 486AMD, EUR - 545AMD Equities Market In March, 2019, 3 trades with total value of AMD 1,219,200 were concluded in the equities market. 548 stocks of 2 issuers were traded. Compared to the same period of the previous year (Mar-18) the number of trades, the number of stocks traded and the total value traded decreased by -57.143%, -99.446% and -95.070%, respectively,. -

Keeping Gunpowder Dry Minsk Hosts the Council of Defence Ministers of the Commonwealth of Independent States

FOCUS The Minsk Times Thursday, June 13, 2013 3 Keeping gunpowder dry Minsk hosts the Council of Defence Ministers of the Commonwealth of Independent States By Dmitry Vasiliev Minsk is becoming ever more a centre for substantive discussions on integration. Following close on the heels of the Council of CIS Heads of Government and the Forum of Busi- nessmen, Minsk has hosted the CIS Council of Defence Ministers. The President met the heads of delegations before the Council began its work, noting, “We pay special im- portance to each event which helps strengthen the authority of our integra- tion association and further develop co-operation among state-partici- pants in all spheres.” Issues of defence and national security are, naturally, of great importance. The President added, “Bearing in mind today’s dif- ficult geopolitical situation worldwide, this area of integration is of particular importance for state stability and the sustainable development of the Com- monwealth.” Belarus supports the further all- round development of the Common- BELTA Prospective issues of co-operation discussed in Minsk at meeting of Council of CIS Defence Ministers wealth, strengthening its defence capa- bility and authority: a position shared any independence... We, Belarusians mark event in the development of close the military sphere is a component of sites in Russia and Kazakhstan and an by many heads of state considering and Russians, don’t have any secrets partnerships in the military sphere. integration, with priorities defined by international competition for the pro- integration. The President emphasised, from each other. If we don’t manage to Last year, the CIS Council of De- the concerns of friendly countries re- fessional military is planned: Warriors “Whether we like it or not, life forces achieve anything (Russia also has prob- fence Ministers — a high level inter- garding sudden complications in the of the Commonwealth. -

The Travel Guide

Travel 1. Arriving by airplane Minsk National Airport (MSQ) There are several Airlines that operate at Minsk National Airport, such as Belavia, Aeroflot, Airbaltic and Lufthansa. The airport is about 50 km from Minsk. An alternative low-budget connection to Minsk is to fly to Vilnius International Airport (VNO) and take the train from Vilnius to Minsk. Several low-cost airlines operate at Vilnius International Airport. The Vilnius International airport is about 200 km from Minsk and train are frequently operating between Minsk and Vilnius (see information below). Important! If you will choose this option you need to have a valid visa or a valid passport allowing to stay visa-free in Belarus. Information about visa process is in General information. Transport from the airport (MSQ) to the Minsk Central station (Minsk Tsentralnyi) Minsk Tsentralnyi is a bus stop near Minsk Central Train station (Babrujskaja 6). By bus: BUS № 300Э You can buy a ticket via the ticket machine at the airport, at the bus station by credit card, from a ticket agent at the bus stop or from bus driver by cash (BYN only). You can exchange money at the airport. The bus stop is located in front of Gate 5-6 (arrival hall). Journey time: 1 hour. Bus timetable: From National Airport Minsk (MSQ) to Minsk Central (Minsk Tsentralnyi) 4:50, 6:25, 7:20, 8:00, 9:00, 9:40, 10:20, 11:20, 12:00, 12:40, 13:20, 14:20, 15:00, 15:40, 16:20, 17:00, 17:40, 18:20, 19:00, 20:00, 20:40, 21:20, 22:05, 23:00, 00:05, 1:45, 3:15 By taxi: You can pay by credit card and order taxi online. -

Note N°57/20 Russia's Policy Towards Belarus During Alyaksandr

Note n°57/20 August 3, 2020 Milàn Czerny Graduated from the Department of War Studies, King’s College London Analyst – Le Grand Continent (GEG), Paris Russia’s policy towards Belarus during Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s fifth presidential term Introduction Belarus and Ukraine compose the core of the « Russian world » (Russkiy Mir), a geopolitical and ideologically constructed space centered around Moscow and based on common civilizational, historical, linguistic, and spiritual ties between the three countries1. Russia’s depiction of this space as a united whole has been deeply shattered since 2014 and the beginning of the war in Ukraine opposing Russian-backed rebels to Ukrainian forces. In this context, Belarus holds a significant symbolic and strategic value for Russia’s policy towards post-Soviet states. Indeed, because of the close historical and civilizational ties between Russia and Belarus, the Belarusian president, Alyaksandr Lukashenka, is a show-case ally necessary for Moscow’s status as a regional leader in the post-Soviet space2. Despite some tensions between Russia and Belarus in the 2000s, for instance around trade issues in 2009, a bargain was established between the two 1 Vladimir Putin has put forward the concept of « Russian world » during his second presidential term (2004-2008) with the support of the Russian Orthodox Church with a view to stressing the ties between Russia and its neighbors based on an essentialist representation of Russian language and culture. The concept serves to legitimize Russian foreign policy toward Ukraine and Belarus by relativizing the borders between the three state and stress Russia’s role as a « natural » leader in the region. -

Public Opinion Survey: Residents of Armenia

Public Opinion Survey: Residents of Armenia February 2021 Detailed Methodology • The survey was conducted on behalf of “International Republican Institute’s” Center for Insights in Survey Research by Breavis (represented by IPSC LLC). • Data was collected throughout Armenia between February 8 and February 16, 2021, through phone interviews, with respondents selected by random digit dialing (RDD) probability sampling of mobile phone numbers. • The sample consisted of 1,510 permanent residents of Armenia aged 18 and older. It is representative of the population with access to a mobile phone, which excludes approximately 1.2 percent of adults. • Sampling frame: Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia. Weighting: Data weighted for 11 regional groups, age, gender and community type. • The margin of error does not exceed plus or minus 2.5 points for the full sample. • The response rate was 26 percent which is similar to the surveys conducted in August-September 2020. • Charts and graphs may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding. • The survey was funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development. 2 Weighted (Disaggregated) Bases Disaggregate Disaggregation Category Base Share 18-35 years old n=563 37% Age groups 36-55 years old n=505 34% 56+ years old n=442 29% Male n=689 46% Gender Female n=821 54% Yerevan n=559 37% Community type Urban n=413 27% Rural n=538 36% Primary or secondary n=537 36% Education Vocational n=307 20% Higher n=665 44% Single n=293 19% Marital status Married n=1,059 70% Widowed or divorced n=155 10% Up -

YRV-Yerevan-092619.Pdf

English | Dutch English | Dutch U.S. Embassy E Yerevan, Armenia n g Contact information English | Dutch Please follow the steps below before your immigrant visa interview at the U.S. Embassy in Yerevan, Armenia. U.S. Embassy i 1 American Avenue s Yerevan 0082, h Register your appointment online Step 1: Republic of Armenia | You need to register your appointment online. Registering your appointment Phone: G provides us with the information we need to return your passport to you after your (+37410) 464-700 e r interview. Registration is free. Click the “Register” button below to register. Email: m [email protected] If you want to cancel or reschedule your appointment, you will be able to do so after a you register your appointment. Website: n armenia.usembassy.gov Cancel and Reschedule: Register ais.usvisa-info.com Map: Step 2: Get a medical exam in Armenia As soon as you receive your appointment date, you must schedule a medical exam in Armenia. Click the “Medical Exam Instructions” button below for a list of designated doctors’ offices in Armenia. Please schedule and attend a medical exam with one of these doctors before your interview. Medical Exam Instructions Other links Diversity visa instructions After your interview Step 3: Complete your pre-interview checklist Frequently asked questions It is important that you bring all required original documents to your interview. We’ve Where to find civil documents created a checklist that will tell you what to bring. Please print the checklist below and bring it to your interview along with the listed documents. -

PRESS RELEASE 18.09.2020 GPW Intends to Take Over the Armenia Securities Exchange · the Warsaw Stock Exchange (GPW) Has S

PRESS RELEASE 18.09.2020 GPW Intends to Take Over the Armenia Securities Exchange · The Warsaw Stock Exchange (GPW) has signed a term sheet with the Central Bank of Armenia (CBA) on negotiations concerning the acquisition of 65% of the Armenia Securities Exchange (AMX) from CBA · GPW’s potential acquisition of AMX requires among others a due diligence and necessary corporate approvals · The preliminary estimated valuation of 100% of AMX is approx. PLN 6 million (USD 1.6 million) On 18 September 2020, the Warsaw Stock Exchange (GPW) Management Board and the Central Bank of Armenia (CBA) signed a term sheet concerning negotiations to purchase 65% majority interest in the Armenia Securities Exchange (AMX) by GPW. The agreement is not binding. The final terms of the acquisition will depend among others on results of due diligence and necessary corporate approvals. “The relations established between GPW and the Central Bank of Armenia spell good news for both parties of the agreement. Many sectors of Armenia’s economy are looking for quality investments so the country has a huge growth potential. Investments are a driver of economic growth, especially in the emerging markets. In my opinion, GPW’s acquisition of AMX would put the Armenian capital market on fast track to growth while the Warsaw Stock Exchange could make satisfying returns on the investment. It is relevant, as well, that Poland is promoting emerging markets. This is a good direction,” said Jacek Sasin, Poland’s Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of State Assets. The term sheet signed by GPW and CBA defines the framework conditions of further negotiations aiming at a potential investment agreement. -

THE BALTICS Oct 22 - Nov 4, 2015

Join Rabbi Stephanie Bernstein & Temple Rodef Shalom on a Jewish Heritage tour of THE BALTICS Oct 22 - Nov 4, 2015 This amazing tour includes... 3 nights at the Radisson Blue Hotel in Riga 2 nights at Park Inn Radisson in Kaunus 2 nights at the Kempinski Hotel in Vilnius 5 nights at the Renaissance Hotel in Minsk Breakfast daily Old Riga Shabbat dinner in Riga Shabbat dinner & farewell dinner in Minsk Arrival & departure transfers with main group Entrance fees & porterage per itinerary Touring in a deluxe air-conditioned vehicle Vilnius Expert English-speaking guide throughout MInsk On This Outstanding Journey, together we will… Explore the Jewish Heritage story and enrich our knowledge of Jewish History in Riga, Kaunus, Vilnius & Minsk. Experience all that the Baltics have to offer. Confront the stories of the past and celebrate the re-birth of the communities of today and tomorrow in the region. Complete attached registration or register online at: www.ayelet.com P 800-237-1517 • F 518-783-6003 www.ayelet.com/BernsteinOct2015.aspx 19 Aviation Rd., Albany, NY 12205 ® On our adventure together, we will... • Visit the important historical places of Riga’s Jewish community including the museum “Jews in Latvia” and places of commemoration of the holocaust of World War II, Bikernieki and Salaspils • Enjoy the splendors of the Dome Cathedral, the Castle of Riga & St. Peter’s Church • Tour Slobodka, a Jewish suburb of pre-war Kaunas and the site of the ghetto during WWII TOUR PRICING Full Discounted Price per person • See the home of Leah Goldberg -

Colliers CEE Report

EX DING BORDERS OFFICE MARKET IN 15 CEE COUNTRIES October 2019 OFFICE MARKET IN 15 CEE COUNTRIES INTRODUCTION CONTENTS 2 Welcome to our publication about the office sector in Central and Eastern Europe. The report presents the situation in the office markets in 15 CEE countries (Albania, Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, INTRODUCTION Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Ukraine). In the study, we focused on key market indicators such as total office stock, take-up and leasing conditions, vacancy levels, space under construction and a forecast for the upcoming years. The presentation of the office market in each country is also enriched with a short commentary, an interesting fact from the market and photos of modern office projects. 4-5 The report has been divided into 3 parts: • A map presenting 15 CEE countries with key economic data; ECONOMIC DATA • The comparative part, where on aggregated charts we present H1 2019 office market data for 15 CEE countries; • Presentation of the office market in each country. In recent years, the CEE region has been characterized by dynamic development, which goes hand in hand with the growth of modern office projects. We forecast that by 2021 the total office stock in the 2 6-7 15 CEE countries will exceed 30 million m . More and more office buildings can boast of prestigious certificates, modern technological and environmental solutions or an innovatively designed space. OFFICE MARKET We believe that thanks to this publication the potential of the 15 CEE countries will be rediscovered IN 15 CEE COUNTRIES IN H1 2019 and will be further developed. -

NEWSLETTER July 2018 FEAS New Members WELCOME OUR NEW MEMBERS

FEAS NEWSLETTER July 2018 FEAS New Members WELCOME OUR NEW MEMBERS. THANKS FOR JOINING FEAS! On June 29th, 2018 FEAS held it's 25th Extraordinary General Assembly. Participating Members: Abu Dhabi Stock Exchange, Amman Stock Exchange, Athens Stock Exchange, Belarusian Currency and Stock Exchange, Bucharest Stock Exchange, Cyprus Stock Exchange, Damascus Securities Exchange, Egyptian Exchange, Iran Fara Bourse, Iran Mercantile Exchange, Iraq Stock Exchange, Kazakhstan Stock Exchange, Muscat Securities Market, NASDAQ OMX Armenia, Palestine Stock Exchange, Republican Stock Exchange "Toshkent", Tehran Stock Exchange, EBRD, Central Depository of Armenia, CSD Iran, Securities and Exchange Brokers Association (SEBA), Securities Depository Center of Jordan and Tehran Stock Exchange Tech. Mgnt. Co. We are very happy to inform that during the General Assembly it was decided to: 1. Admit Boursa Kuwait and Misr for Central Clearing, Depository and Registry (MCDR) full member status. 2. Admit Moldova Stock Exchange as an Observer. 3. Change the status of Central Depository of Armenia /CDA from affiliate member to full member. 2 July 2018 FEAS FULL MEMBERS FEAS AFFILIATE MEMBERS Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange The European Bank for Reconstruction Amman Stock Exchange and Development (EBRD) Athens Stock Exchange SA Central Securities Depository of Iran Belarusian Currency and Stock Securities & Exchange Brokers Exchange Association Securities Depository Center of Jordan Boursa Kuwait Tehran Securities Exchange Technology Bucharest Stock Exchange Management -

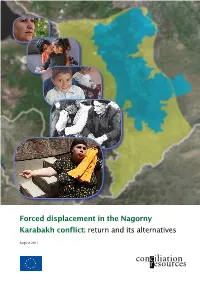

Forced Displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh Conflict: Return and Its Alternatives

Forced displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict: return and its alternatives August 2011 conciliation resources Place-names in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict are contested. Place-names within Nagorny Karabakh itself have been contested throughout the conflict. Place-names in the adjacent occupied territories have become increasingly contested over time in some, but not all (and not official), Armenian sources. Contributors have used their preferred terms without editorial restrictions. Variant spellings of the same name (e.g., Nagorny Karabakh vs Nagorno-Karabakh, Sumgait vs Sumqayit) have also been used in this publication according to authors’ preferences. Terminology used in the contributors’ biographies reflects their choices, not those of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. For the map at the end of the publication, Conciliation Resources has used the place-names current in 1988; where appropriate, alternative names are given in brackets in the text at first usage. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. Altered street sign in Shusha (known as Shushi to Armenians). Source: bbcrussian.com Contents Executive summary and introduction to the Karabakh Contact Group 5 The Contact Group papers 1 Return and its alternatives: international law, norms and practices, and dilemmas of ethnocratic power, implementation, justice and development 7 Gerard Toal 2 Return and its alternatives: perspectives