Soviet Partisan 1941–44

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50 CALIBER (12.7MM) HEAVY MACHINE GUN Reliable, Accurate, Effective

M2HB .50 CALIBER (12.7MM) HEAVY MACHINE GUN Reliable, accurate, effective SPECIFICATIONS s General Dynamics Ordnance and Tactical Systems produc- Caliber .50 caliber / 12.7mm (NATO) es the .50 Caliber M2 Heavy Barrel (M2HB) machine gun, Weight (complete gun) 84 pounds (38.2 kg) a belt-fed, recoil operated, air-cooled, crew-served weapon Length 65.13 inches (1,654mm) capable of right or left-hand feed. The weapon’s lethality, durability and versatility make it ideal for offensive and Width 9 inches (230mm) defensive operations. Cyclic rate of fire 450-600 rounds per minute Maximum effective The M2 machine gun is one of the world’s most reliable, 2,000 yards (1,830m) range highly accurate and effective weapons. Maximum range 7,400 yards (6,766m) The M2HB fires a variety of NATO .50 Caliber ammuni- 3,050 feet per second Muzzle velocity (M33) (930 meters per second) tion to include: ball, tracer, armor-piercing, incendiary, and Barrel weight 26 pounds (11.79 kg) saboted light armor penetrator. The M2HB will deliver lethal Barrel construction cobalt-chromium alloy liner effects against multiple target types. The maximum effec- tive range of the M2HB is 1,830 meters for area targets and 1,500 meters for point targets. M2HB .50 CALIBER (12.7MM) HEAVY MACHINE GUN KEY FEATURES - Sustained automatic or single-shot firing - Durable, rugged design - Fires from the closed bolt for single-shot accuracy - Replaceable heavy barrel assembly - Simple design for ease of maintenance - Adjustable headspace and timing - Converts from left-hand to right-hand feed - Barrel life exceeds 10,000 rounds - Variety of mounting applications - Trigger block safety 11399 16th Court North - Suite 200 - St. -

Trade Marks Inter Parte Decision O/526/20

O-526-20 TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATION NO. 3389020 BY EFE TEMIZEL TO REGISTER: AS A TRADE MARK IN CLASS 25 AND IN THE MATTER OF OPPOSITION THERETO UNDER NO. 417707 BY HANES INNERWEAR AUSTRALIA PTY LTD Background & Pleadings 1. On 2 April 2019, Efe Temizel (“the applicant”) applied to register the above trade mark for a variety of goods in class 25, laid out in their entirety at annex 1 of this decision. The application was published for opposition purposes on 14 June 2019. 2. On 16 September 2019, the application was opposed in full by Hanes Innerwear Australia Pty Ltd (“the opponent”). The opposition is based upon section 5(2)(b) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (“the Act”), in relation to which the opponent relies upon the marks laid out below and all goods for which each is registered: United Kingdom Trade Mark (“UKTM”) 3154319 BOND Class 25: Clothing; footwear; headgear; swimwear; sportswear; leisurewear. Filed on 11 March 2016 Registered on 30 December 2016 International Registration (“IR”) 1377504 Class 25: Clothing; footwear; headgear. Designated the UK on 1 November 2017 Granted protection in the UK on 3 May 2018 IR 801821 Class 25: Clothing, footwear and headgear. Designated the UK on 9 November 2017 Granted protection in the UK on 24 May 2018 1 European Union Trade Mark (“EUTM”) 17459371 BONDS Class 25: Clothing, footwear, headgear. Filed on 10 November 2017 Registered on 8 May 2018 3. In its Notice of Opposition, the opponent submits that the similarity between the respective trade marks, coupled with the similarity, or identity, between the respective goods would result in a likelihood of confusion on the part of the relevant public. -

Machine Guns

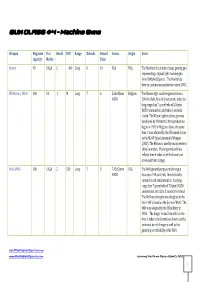

GUN CLASS #4 – Machine Guns Weapon Magazine Fire Recoil ROF Range Reloads Reload Ammo Origin Notes capacity Modes Time Morita 99 FA,SA 2 400 Long 6 10 N/A N/A The Morita is the standard issue gaming gun representing a typical light machine gun from Battlefield Sports. The Morita has been in continuous manufacture since 2002. FN Minimi / M249 200 FA 2 M Long 7 6 5.56x45mm Belgium The Minimi light machine gun features a NATO 200 shot belt, fires fully automatic only, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 5.56mm NATO ammunition, and takes 6 seconds reload. The Minimi light machine gun was developed by FN Herstal. Mass production began in 1982 in Belgium. About the same time it was adopted by the US Armed forces as the M249 Squad Automatic Weapon (SAW). The Minimi is used by many western allied countries. The longer reload time reflects time it takes to let the barrel cool down and then change. M60 GPMG 100 FA,SA 2 550 Long 7 8 7.62x51mm USA The M60 general purpose machine gun NATO features a 100 shot belt, fires both fully automatic and semiautomatic, has long range, has 7 spare belts of 7.62mm NATO ammunition and takes 8 seconds to reload. The M60 machine gun was designed in the late 1940's based on the German MG42. The M60 was adopted by the US military in 1950. .The longer reload time reflects the time it takes to let barrel cool down and the awkward barrel change as well as the general poor reliability of the M60. -

”Shoes”: a Componential Analysis of Meaning

Vol. 15 No.1 – April 2015 A Look at the World through a Word ”Shoes”: A Componential Analysis of Meaning Miftahush Shalihah [email protected]. English Language Studies, Sanata Dharma University Abstract Meanings are related to language functions. To comprehend how the meanings of a word are various, conducting componential analysis is necessary to do. A word can share similar features to their synonymous words. To reach the previous goal, componential analysis enables us to find out how words are used in their contexts and what features those words are made up. “Shoes” is a word which has many synonyms as this kind of outfit has developed in terms of its shape, which is obviously seen. From the observation done in this research, there are 26 kinds of shoes with 36 distinctive features. The types of shoes found are boots, brogues, cleats, clogs, espadrilles, flip-flops, galoshes, heels, kamiks, loafers, Mary Janes, moccasins, mules, oxfords, pumps, rollerblades, sandals, skates, slides, sling-backs, slippers, sneakers, swim fins, valenki, waders and wedge. The distinctive features of the word “shoes” are based on the heels, heels shape, gender, the types of the toes, the occasions to wear the footwear, the place to wear the footwear, the material, the accessories of the footwear, the model of the back of the shoes and the cut of the shoes. Keywords: shoes, meanings, features Introduction analyzed and described through its semantics components which help to define differential There are many different ways to deal lexical relations, grammatical and syntactic with the problem of meaning. It is because processes. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Army Guide Monthly • Issue #3 (102)

Army G uide monthly # 3 (102) March 2013 Savings Served Up for Bradley Armor Plates Tachanka Hwacha Patria Delivered 1st Batch of NextGen Armoured Wheeled Vehicles to Sweden Micro-robotics Development Furthered with ARL Contract Extension Textron Marine & Land Systems to Build 135 Additional Mobile Strike Force Vehicles Saab Acquires Ballistic Protection Technology Scale Armour Textron Awarded Contract to Produce Turrets and Provide Support for Colombia's APCs US Army Developing New 120mm AMP Tank Round Siege Engine Heavy Tank Medium Tank Tanegashima Super-Heavy Tank www.army-guide.com Army Guide Monthly • #3 (102) • March 2013 Army to change the armor tile box material from titanium to Savings Served Up for Bradley Armor aluminum for more than 800 reactive armor tile sets. Plates "They wanted to change the material for several reasons," said Peter Snedeker, a contracting officer with ACC-New Jersey. "It was easier to manufacture with aluminum rather than titanium, so there would be shorter lead times. Aluminum was also more readily available and cheaper." However, changing a contract isn't a simple matter. The change can't have a material effect on the design, nor can performance be less than what the contract requires. The aluminum must perform just as well or better than titanium to support the demands of the Soldier. When a military contractor approached the Army ACC-New Jersey's technical team performed an with a proposal for significant savings on armor extensive analysis of the change proposal and continued tiles for the Bradley Fighting Vehicle, the impulse to to work with General Dynamics to determine if the quickly go for the savings had to be postponed: The Bradley played such an important role in saving material switch served the form, fit and function lives that keeping a steady flow of contracts was specified in the technical data package. -

American Army

ASSAULT PLATOON AMERICAN ARMY MASSIMO TORRIANI – VALENTINO DEL CASTELLO - Copyright 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, including mechanical and/or electronic methods, without the author’s prior written permission. For updates: www.torrianimassimo.it Version December 2013 1 AMERICAN ARMY (1943-1945) BASIC INFANTRY PLATOON The Platoon comprises: 0-1 Infantry HQ Squad (180 points), 2-3 Infantry Squads (370 points each) INFANTRY HQ SQUAD Infantry Unit, HQ Breakpoint: 2 TV: 3 No. Model Weapon Characteristics M1 semi-automatic carbine, Colt 1911A1 pistol, MKII 1 Lieutenant HQ leader Pineapple grenades 1 Second Lieutenant M1 semi-automatic carbine, MKII Pineapple grenades HQ leader 1 Sergeant M1 semi-automatic carbine, MKII Pineapple grenades HQ leader 2 Riflemen Garand M1 semi-automatic rifle, MKII Pineapple grenades INFANTRY SQUAD Infantry Unit Breakpoint: 5 TV: 3 No. Model Weapon Characteristics 1 Sergeant M1 semi-automatic carbine, MKII Pineapple grenades leader 1 Corporal M1 semi-automatic carbine, MKII Pineapple grenades leader 1 Machine-gunner BAR M1918A2 automatic rifle, MKII Pineapple grenades 9 Riflemen Garand M1 semi-automatic rifle, MKII Pineapple grenades SPLITTING UP AN INFANTRY SQUAD Each Infantry Squad can be split up into two Sections: the first comprising a Sergeant and 6 Riflemen (BRK 3) and the other comprising the Corporal, the Machine-gunner and 3 Riflemen (BRK 2). VARIANTS: You can add a radio to the HQ Squad for +10 points. One of the riflemen in the Squad gets the radio characteristic. Leaders can replace their M1 semi-automatic carbines with M3A1 Grease Gun sub-machine guns for free. -

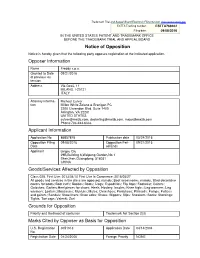

Notice of Opposition Opposer Information Applicant Information

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA769402 Filing date: 09/08/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Notice of Opposition Notice is hereby given that the following party opposes registration of the indicated application. Opposer Information Name Freddy s.p.a. Granted to Date 09/21/2016 of previous ex- tension Address Via Gesù, 11 MILANO, I-20121 ITALY Attorney informa- Michael Culver tion Millen White Zelano & Branigan PC 2200 Clarendon Blvd. Suite 1400 Arlington, VA 22201 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Phone:703-243-6333 Applicant Information Application No 86857876 Publication date 05/24/2016 Opposition Filing 09/08/2016 Opposition Peri- 09/21/2016 Date od Ends Applicant Lingsu Qiu 29B,Building 6,Weipeng Garden,No.1 Shenzhen,Guangdong, 518031 CHINA Goods/Services Affected by Opposition Class 025. First Use: 2013/04/10 First Use In Commerce: 2015/05/27 All goods and services in the class are opposed, namely: Boot accessories, namely, fitted decorative covers for boots; Boot cuffs; Booties; Boots; Clogs; Espadrilles; Flip flops; Footwear; Gaiters; Galoshes; Garters;Heel pieces for shoes; Heels; Hosiery; Insoles; Knee highs; Leg-warmers; Leg warmers; Loafers; Moccasins; Mukluks; Mules; Overshoes; Pantyhose; Plimsolls; Pumps; Puttees and gaiters; Sandals; Shoe liners; Shoe soles; Shoes; Slippers; Slips; Sneakers; Socks; Stockings; Tights; Toe caps; Valenki; Zori Grounds for Opposition Priority and likelihood of confusion Trademark Act Section 2(d) Marks Cited by Opposer as Basis for Opposition U.S. -

Mg 34 and Mg 42 Machine Guns

MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS MC NAB © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com MG 34 AND MG 42 MACHINE GUNS CHRIS McNAB Series Editor Martin Pegler © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 DEVELOPMENT 8 The ‘universal’ machine gun USE 27 Flexible firepower IMPACT 62 ‘Hitler’s buzzsaw’ CONCLUSION 74 GLOSSARY 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY & FURTHER READING 78 INDEX 80 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com INTRODUCTION Although in war all enemy weapons are potential sources of fear, some seem to have a deeper grip on the imagination than others. The AK-47, for example, is actually no more lethal than most other small arms in its class, but popular notoriety and Hollywood representations tend to credit it with superior power and lethality. Similarly, the bayonet actually killed relatively few men in World War I, but the sheer thought of an enraged foe bearing down on you with more than 30cm of sharpened steel was the stuff of nightmares to both sides. In some cases, however, fear has been perfectly justified. During both world wars, for example, artillery caused between 59 and 80 per cent of all casualties (depending on your source), and hence took a justifiable top slot in surveys of most feared tools of violence. The subjects of this book – the MG 34 and MG 42, plus derivatives – are interesting case studies within the scale of soldiers’ fears. Regarding the latter weapon, a US wartime information movie once declared that the gun’s ‘bark was worse than its bite’, no doubt a well-intentioned comment intended to reduce mounting concern among US troops about the firepower of this astonishing gun. -

Nestor Makhno in the Russian Civil War.Pdf

NESTOR MAKHNO IN THE RUSSIAN CIVIL WAR Michael Malet THE LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE TeutonicScan €> Michael Malet \982 AU rights reserved. No parI of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, wilhom permission Fim ed/lIOn 1982 Reprinted /985 To my children Published by lain, Saffron, and Jonquil THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London rind BasingSloke Compafl/u rind reprutntatiW!S throughout the warld ISBN 0-333-2S969-6 Pnnted /II Great Bmain Antony Rowe Ltd, Ch/ppenham 5;landort � Signalur RNB 10043 Akz.·N. \d.·N. I, "'i • '. • I I • Contents ... Acknowledgements VIII Preface ox • Chronology XI .. Introduction XVII Glossary xx' PART 1 MILITARY HISTORY 1917-21 1 Relative Peace, 1917-18 3 2 The Rise of the Balko, July 19I5-February 1919 13 3 The Year 1919 29 4 Stalemate, January-October 1920 54 5 The End, October I92O-August 1921 64 PART 2 MAKHNOVSCHYNA-ORGAN1SATION 6 Makhno's Military Organisation and Capabilities 83 7 Civilian Organisation 107 PART 3 IDEOLOGY 8 Peasants and Workers 117 9 Makhno and the Bolsheviks 126 10 Other Enemies and Rivals 138 11 Anarchism and the Anarchists 157 12 Anti-Semitism 168 13 Some Ideological Questions 175 PART 4 EXILE J 4 The Bitter End 183 References 193 Bibliography 198 Index 213 • • '" Acknowledgements Preface My first thanks are due to three university lecturers who have helped Until the appearance of Michael PaJii's book in 1976, the role of and encouraged me over the years: John Erickson and Z. A. B. Nestor Makhno in the events of the Russian civil war was almost Zeman inspired my initial interest in Russian and Soviet history, unknown. -

Classic Arms (Pty) Ltd Is Proud to Present Its 60Th Auction of Collectable, Classic, Sporting & Other Arms, Accoutrements and Edged Weapons

Classic Arms (Pty) Ltd Is proud to present its 60th Auction Of Collectable, Classic, Sporting & Other Arms, Accoutrements and Edged Weapons. The Portuguese Club, Nita Street, Del Judor X4, Witbank on 24 March 2018 Viewing will start at 09:00 and Auction at 12:00 Enquiries: Tel: 013 656 2923 Fax: 013 656 1835 Email: [email protected] CATEGORY A ~ COLLECTABLES Lot # Lot Description Estimate A1 British Mk111 WW1 Flare Pistol R 1500.00 Brass pistol with wooden grips. Marked to, "Chubb London & Wolverhampton". Various British military acceptance & ownership stamps, dated 1915. Good plus condition but for missing latch spring. A2 Webley Senior No. 2 Air Pistol R 1500.00 Dark brown chequered grips, 6,7" barrel, blued finish. All good original condition. A3 US Military Pattern Colt 1911 & P-38 Holster R 400.00 Hinged swivel US marked flap with holster allowing left or right handed use. Appears to be a good repro. Used German military type P-38 Walther holster with mag pouch & flap cover. Both good used condition. A4 Martini Fore-Ends x 3 R 1750.00 Martini-Enfield fore-ends x 2, one with fore-end cap. One x Martini-Henry rifle fore- end. A5 Zeiss Conquest HD5 5-25X50 Rifle Scope R 12500.00 In manufacturer's box with RZ Varmint reticule. Complete with instruction manual etc. Scope appears to be brand new. A6 Nikon Monarch 2,5-10 x 42 Rifle Scope R 4500.00 Mildot model with a matte finish. In manufacturer's box with warranty forms etc. Scope appears to be brand new. -

Ukraine 2014

TheRaising Chinese Red Flags: QLZ87 Automatic Grenade An Examination of Arms & Munitions in the Ongoing LauncherConflict in Ukraine 2014 Jonathan Ferguson & N.R. Jenzen-Jones RESEARCH REPORT No. 3 COPYRIGHT Published in Australia by Armament Research Services (ARES) © Armament Research Services Pty. Ltd. Published in November 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Armament Research Services, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organisation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Armament Research Services: [email protected] CREDITS Authors: Jonathan Ferguson & N.R. Jenzen-Jones Contributors: Yuri Lyamin & Michael Smallwood Technical Review: Yuri Lyamin, Ian McCollum & Hans Migielski Copy Editor: Jean Yew Layout/Design: Yianna Paris, Green Shell Media ABOUT ARMAMENT RESEARCH SERVICES Armament Research Services (ARES) is a specialist consultancy which offers technical expertise and analysis to a range of government and non-government entities in the arms and munitions field.ARES fills a critical market gap, and offers unique technical support to other actors operating in the sector. Drawing on the extensive experience and broad-ranging skillsets of our staff and contractors, ARES delivers full-spectrum research and analysis, technical review, training, and project support services, often in support of national, regional, and international initiatives. ARMAMENT RESEARCH SERVICES Pty. Ltd. t + 61 8 6365 4401 e [email protected] w www.armamentresearch.com Jonathan Ferguson & N.R.