Headaches in the Whiplash Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neck Pain Exercises

Information and exercise sheet NECK PAIN Neck pain usually gets better in a few weeks. You with your shoulders and neck back. Don’t wear a neck can usually treat it yourself at home. It’s a good idea collar unless your doctor tells you to. Neck pain usually to keep your neck moving, as resting too much could gets better in a few weeks. Make an appointment with make the pain worse. your GP or a physiotherapist if your pain does not improve, or you have other symptoms, such as: This sheet includes some exercises to help your neck pain. It’s important to carry on exercising, even • pins and needles when the pain goes, as this can reduce the chances • weakness or pain in your arm of it coming back. Neck pain can also be helped by • a cold arm sleeping on a firm mattress, with your head at the • dizziness. same height as your body, and by sitting upright, Exercises Many people find the following exercises helpful. 1 If you need to, adjust the position so that it’s comfortable. Try to do these exercises regularly. Do each one a few times to start with, to get used to them, and gradually increase how much you do. 1. Neck stretch Keeping the rest of the body straight, push your chin forward, so your throat is stretched. Gently tense your neck muscles and hold for five seconds. Return your head to the centre and push it backwards, keeping your chin up. Hold for five seconds. Repeat five times. -

Neck Pain Begins

www.southeasthealth.org Where Neck Pain Begins Overview Neck pain is a common problem that severely impacts the quality of your life. It can limit your ability to be active. It can cause you to miss work. Many different causes may lead to pain in your neck. About the Cervical Spine Let's learn about the structure of the cervical spine to better understand neck pain. Your cervical spine is made up of seven cervical vertebrae. Between these vertebrae are discs. They cushion the bones and allow your neck to bend and twist. Spinal Cord and Nerves The spine protects your spinal cord, which travels through a space called the spinal canal. Branches of spinal nerves exit the spine through spaces on both sides of your spine. These travel down to your shoulders and arms. Common Causes of Pain In many cases, neck pain is muscle-related. Muscle tension, cramps and strains can all cause discomfort. Neck pain can also be caused by compression of the spinal nerves. Herniated discs or bone growths caused by osteoarthritis can press against the nerves. Fractures of the spine can reduce the amount of space around them. This type of pain may not go away, even after weeks. Symptoms Symptoms of neck pain can vary depending on the cause of your pain and the severity of your injury. You may have muscle spasms. You may have headaches. You may have trouble bending and rotating your neck. These symptoms may get worse with movement. Problems in the neck can also cause pain in your shoulders. -

Pain Management in Ehlers Danlos Syndrome

Ehlers-Danlos Naonal Foundaon August 2013 Conference Pain management in Ehlers Danlos Syndrome Pradeep Chopra, MD, MHCM Director, Pain Management Center, Assistant Professor, Brown Medical School, Rhode Island Assistant Professor (Adjunct), Boston University Medical Center [email protected] [email protected] Pradeep Chopra, MD 1 Disclosure and disclaimer • I have no actual or poten.al conflict of interest in relaon to this presentaon or program • This presentaon will discuss “off-label” uses of medicaons • Discussions in this presentaon are for a general informaon purposes only. Please discuss with your physician your own par.cular treatment. This presentaon or discussion is NOT meant to take the place of your doctor. Pradeep Chopra, MD 2 All rights reserved. 1 Ehlers-Danlos Naonal Foundaon August 2013 Conference Introduc.on • Training and Fellowship, Harvard Medical school • Pain Medicine specialist • Assistant Professor – Brown Medical School, Rhode Island Pradeep Chopra, MD 3 Pain in EDS by body parts • Head and neck • Shoulders • Jaws • Chest • Abdomen • Hips • Lower back • Legs • Complex Regional Pain Syndrome – CRPS or RSD Pradeep Chopra, MD 4 All rights reserved. 2 Ehlers-Danlos Naonal Foundaon August 2013 Conference Pain in EDS • From nerves – neuropathic • From muscles – Myofascial • From Joints – nocicep.ve pain • Headaches Pradeep Chopra, MD 5 Muscle pain Myofascial pain Pradeep Chopra, MD 6 All rights reserved. 3 Ehlers-Danlos Naonal Foundaon August 2013 Conference Muscle Pain • Muscles are held together by fascia – ‘saran wrap’ which is made of collagen • Muscle spasms or muscle knots develop to compensate for unbalanced forces from the joints Pradeep Chopra, MD 7 Muscle pain 1 • Most chronic pain condi.ons are associated with muscle spasms • Oben more painful than the original pain • Muscles may .ghten reflexively, guarding of a painful area, nerve irritaon or generalized tension Pradeep Chopra, MD 8 All rights reserved. -

Neck Pain, Joint Quality of Life (2)

National Health Statistics Reports Number 98 October 12, 2016 Use of Complementary Health Approaches for Musculoskeletal Pain Disorders Among Adults: United States, 2012 by Tainya C. Clarke, M.P.H., Ph.D., National Center for Health Statistics; Richard L. Nahin, M.P.H., Ph.D., National Institutes of Health; Patricia M. Barnes, M.A., National Center for Health Statistics; and Barbara J. Stussman, National Institutes of Health Abstract Introduction Objective—This report examines the use of complementary health approaches Pain is a leading cause of disability among U.S. adults aged 18 and over who had a musculoskeletal pain disorder. and a major contributor to health care Prevalence of use among this population subgroup is compared with use by persons utilization (1). Pain is often associated without a musculoskeletal disorder. Use for any reason, as well as specifically to treat with a wide range of injury and disease. musculoskeletal pain disorders, is examined. It is also costly to the United States, not Methods—Using the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, estimates of the just in terms of health care expenses use of complementary health approaches for any reason, as well as use to treat and disability compensation, but musculoskeletal pain disorders, are presented. Statistical tests were performed to also with respect to lost productivity assess the significance of differences between groups of complementary health and employment, reduced incomes, approaches used among persons with specific musculoskeletal pain disorders. lost school days, and decreased Musculoskeletal pain disorders included lower back pain, sciatica, neck pain, joint quality of life (2). The focus of this pain or related conditions, arthritic conditions, and other musculoskeletal pain report is on somatic pain affecting disorders not included in any of the previous categories. -

The Global Spine Care Initiative: a Summary of the Global Burden of Low Back and Neck Pain Studies

European Spine Journal https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5432-9 REVIEW The Global Spine Care Initiative: a summary of the global burden of low back and neck pain studies Eric L. Hurwitz1 · Kristi Randhawa2,3 · Hainan Yu2,3 · Pierre Côté2,3 · Scott Haldeman4,5,6 Received: 9 July 2017 / Accepted: 16 December 2017 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract Purpose This article summarizes relevant fndings related to low back and neck pain from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) reports for the purpose of informing the Global Spine Care Initiative. Methods We reviewed and summarized back and neck pain burden data from two studies that were published in Lancet in 2016, namely: “Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015” and “Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.” Results In 2015, low back and neck pain were ranked the fourth leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally just after ischemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and lower respiratory infection {low back and neck pain DALYs [thousands]: 94 941.5 [95% uncertainty interval (UI) 67 745.5–128 118.6]}. In 2015, over half a billion people worldwide had low back pain and more than a third of a billion had neck pain of more than 3 months duration. -

Cervicogenic Headaches: a Pain in the Neck

www.drayerpt.com VOLUME 12,10, ISSUEISSUE 24 Cervicogenic Headaches: A Pain in the Neck By Jessica Heath and Neal Goulet This study also indicated If you stick your neck out that CGH affects four times for someone, the saying suggests, more women than men. Neck then you’ve taken some risk. positions and specific occupa- In this technology-driven tions, such as hairdressing, car- age, we’re literally sticking our pentry and truck/tractor driv- necks out at the risk of causing ing, have been linked to CGH. very real headache pain. An Diagnosis of CGH can be article in Men’s Journal used tricky because it can resemble the term “the desk worker’s other headaches and can trig- malady,” while a BBC story ger other headaches, such as called it “text neck.” a migraine. “The problem is that we’re Doctors may look for the craning our heads forward over source of the pain by attempt- our screens,” according to the ing to use a nerve block. This BBC, “and it’s creating intense involves an injection into the pressure on the front and backs neck of an anesthetic that can of our necks.” What feels like a dull, achy pain in the head really has its roots help determine which nerve is That pressure can cause in the neck. causing the pain. pain that manifests as a Those suffering from headache. This pain actually spine, comprising seven bones Common causes of CGH headaches try many remedies. isn’t in the head but rather is more commonly known as the can be chronic: poor posture, Medication, massage and even “referred” from the neck. -

Neck Pain WHAT YOU CAN DO

neck pain WHAT YOU CAN DO Neck pain Neck pain is a common problem. Nearly 25 percent of adults will experience neck pain at some time in their lives. Even though neck problems can be painful and frustrating, they are rarely caused by serious diseases. The good news is that most of the time neck pain improves within 4 to 6 weeks. Follow the tips in this booklet to help you feel better and get back to your normal activities. Where does neck pain come from? The neck is made up of many different parts, including bones, joints, ligaments, discs, muscles, and nerves. Neck pain can begin in any of these areas. It can be felt in the neck, upper back, shoulders, or sometimes down the arm. Neck problems can also cause headaches. Bones – The bones in the neck are called vertebrae. Joints – A joint is formed where the vertebrae meet. These joints allow the spine to bend and move. Joints lose some of their ability to move as you age. Ligaments – Ligaments are strong bands that hold the bones together. When ligaments are pulled or over-stretched, it is called a sprain. Discs – Discs are made up of many layers. They separate the vertebrae and allow the neck to bend. Like joints, discs can wear down as you age. Muscles – The muscles surrounding your neck give it support and allow you to move. The muscles in the neck and upper back area are very important in helping to maintain good posture. When muscles are pulled or overworked, it is called a strain. -

Cognitive and Mind-Body Therapies for Chronic Low Back and Neck Pain: Effectiveness and Value

Cognitive and Mind-Body Therapies for Chronic Low Back and Neck Pain: Effectiveness and Value Final Evidence Report November 6, 2017 Prepared for ©Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, 2017 AUTHORS: Jeffrey A. Tice, MD Professor of Medicine University of California, San Francisco Varun Kumar, MBBS, MPH, MSc Health Economist, Institute for Clinical and Economic Review Ifeoma Otuonye, MPH Research Associate, Institute for Clinical and Economic Review Margaret Webb, BA Research Assistant, Institute for Clinical and Economic Review Matt Seidner, BS Program Manager, Institute for Clinical and Economic Review David Rind, MD, MSc Chief Medical Officer, Institute for Clinical and Economic Review Rick Chapman, PhD, MS Director of Health Economics, Institute for Clinical and Economic Review Daniel A. Ollendorf, PhD Chief Scientific Officer, Institute for Clinical and Economic Review Steven D. Pearson, MD, MSc President, Institute for Clinical and Economic Review DATE OF PUBLICATION: November 6, 2017 We would also like to thank Patty Synnott, Geri Cramer, Foluso Agboola, Molly Morgan, and Aqsa Mugal for their contributions to this report. ©Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, 2017 Page i Chronic Low Back and Neck Pain – Final Evidence Report About ICER The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) is an independent non-profit research organization that evaluates medical evidence and convenes public deliberative bodies to help stakeholders interpret and apply evidence to improve patient outcomes and control costs. ICER receives funding from government grants, non-profit foundations, health plans, provider groups, and health industry manufacturers. For a complete list of funders, visit http://www.icer- review.org/about/support/. Through all its work, ICER seeks to help create a future in which collaborative efforts to move evidence into action provide the foundation for a more effective, efficient, and just health care system. -

The Burden of Pain Among Adults in the United States

PFIZER FACTS The Bu rden of Pain Among Adults in the United St ates Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, the National Health Care Surveys, and the National Health Interview Survey Medical Division PG283560 © 2008 Pfizer Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in USA/December 2008 The burden of pain among adults in the United States ver 100 million adults in the United States—51% of the estimated 215 million population aged 20 years and older—report pain at one or more body sites including the joints, low back, neck, face/jaw, or experience dental pain or headaches/migraines. OOver one-quarter of adults aged 40 years and older report low back pain in the past 3 months. One-quarter of women aged 20–39 years report having severe headaches or migraines in the past 3 months. Numerous diseases and conditions are also associated with pain, including arthritis, peripheral neuropathy, fibromyalgia, and shingles. Annually, there are 5.4 million ambulatory and inpatient health care visits with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, 1.9 million diabetic neuropathy visits, and 1.5 million shingles visits. 50% of adults with diabetes who have peripheral neuropathy report symptoms of pain/tingling in their feet or numbness/loss of feeling in the past 3 months. 44% of adults with arthritis report limitations in their usual activities due to their arthritis or joint pain. Pain may also be caused by bodily injury or harm. In 2006, there were approximately 34 million injury-related physician office visits. Analgesic drug therapy was reported at 40% of these injury- related visits. -

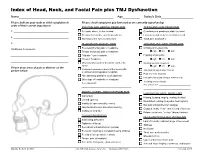

Index of Head, Neck, and Facial Pain Plus TMJ Dysfunction Name______Age______Today’S Date______

Index of Head, Neck, and Facial Pain plus TMJ Dysfunction Name________________________________________________________ Age__________ Today’s Date___________________ Please indicate your main or chief complaints in Please check symptoms you have had or are currently experiencing: order of their current importance: EYE PAIN AND ORBITAL PROBLEMS TEETH AND GUM PROBLEMS 1. _______________________________________ Eye pain, above, below, behind Clenching and grinding at night (bruxism) Pressure behind the eyes (retro-orbital) Looseness and or soreness of back teeth 2. _______________________________________ Watering of the eyes (lacrimation) Tooth pain (toothache) 3. _______________________________________ HEAD AND HEADACHE PAIN JAW AND JAW JOINT PROBLEMS Forehead (frontal) pain or headache Clicking of the jaw joints Additional Comments: Temple (temporal) pain or headache right left both _________________________________________ “Migraine” type headache Popping of jaw joints “Cluster” headache right left both _________________________________________ Maxillary sinus pain or headache (under the Grating sounds (crepitus) eyes) right left both Please draw areas of pain or distress on the Posterior headaches (back of the head) with picture below: Jaw locking opened or closed or without shooting pains (occipital) Pain in cheek muscles Hair and scalp painful to touch (parietal) Uncontrollable jaw, tongue movements Other type of headache or head pain Avoiding certain foods If so, please list: ______________________________ If so, please list: ____________________________ -

Trapezius Myalgia: Making Dentistry a Pain in the Neck — Or Head

Trapezius Myalgia: Making Dentistry a Pain in the Neck — or Head By Bethany Valachi, PT, MS, CEAS By midmorning, it starts ... again; the all-too-familiar "tension headache" that soon evolves into a headache behind the dentist's right eye and pain in his right temple. In an adjacent operatory, the hygienist experiences burning pain on the left side of her neck. Why does this happen? Both clinicians recently embarked upon diligent exercise programs with their personal trainers in an effort to improve their musculoskeletal health and avoid such painful episodes. Does this sound familiar? If so, you're in good company — the incidence of neck pain among dentists and hygienists has been reported as high as 71% and 82% respectively. The causes of headaches and neck pain are multifactorial; however, in dentistry, the upper trapezius muscle is the culprit in a myriad of head and neck pain syndromes. The delivery of dental care places high demands on this muscle and can result in a painful condition called trapezius myalgia. Symptoms include pain, spasms, or tenderness in the upper trapezius muscle, often on the side of the mirror, or retracting arm (Fig. 1). Trigger points in this muscle result in headaches behind the eye, into the temple, and in back of the neck. Fig. 1 The upper left trapezius muscle (shaded). The upper trapezius muscles are responsible for elevating the shoulders and rotating the neck. In rounded shoulder posture, the upper trapezius and neck muscles largely support the arm's weight, increasing muscular strain on the neck and shoulder. In dentistry, trapezius myalgia is caused by static, prolonged elevation of the shoulders, mental stress, infrequent breaks, and poor head posture. -

Visual Index of Head, Neck and Facial Pain and Tmj Dysfunction

VISUAL INDEX OF HEAD, NECK AND FACIAL PAIN AND TMJ DYSFUNCTION A Eye Pain and Eye (orbit) Problems: 1. Eye (orbital) pain; above, below, behind. 2. Bloodshot eyes (hyperemia). 3. Blurring of vision. 4. Bulging appearance (exophthalmia). 5. Pressure behind the eyes (retro-orbital pressure). 6. Light sensitivity (photophobia). 7. Watering of the eyes (lacrimation). 8. Drooping of the eyelid (ptosis). B Head Pain, Headache Problems, Facial Pain: 1. Forehead (frontal) pain. F 2. Temple (temporal) pain. Ear Pain, Ear Problems and Postural 3. “Migraine” type headache. Imbalances: 4. “Cluster-type” Headache. 1. Hissing, buzzing, ringing or roaring sounds 5. Maxillary sinus headache under the eyes (maxillary (tinnitus). sinus pain). 2. Diminished hearing (subjective hearing loss). 6. Posterior, back of head, headaches with or without 3. Ear pain – without infection (otalgia). shooting pains (occipital or parietal headaches). 4. Clogged, stuffy, “itchy” ears, feeling of 7. Hair and/or scalp painful to touch. fullness. 5. Balance problems, “vertigo,” dizziness or C disequilibrium (subjective or objective). Mouth, Face, Cheek and Chin Problems: 1. Discomfort or pain to any of these areas. G 2. Limited opening. Throat Problems: 3. Inability to open the jaw smoothly or evenly. 1. Swallowing difficulties. 4. Jaw deviates to one side when opening. 2. Tightness of throat. 5. Inability to “find bite.” 3. Sore throat without infection (coryza). 4. Voice fluctuations. D 5. Laryngitis. Teeth and Gum Problems: 6. Frequent coughing or constant clearing of 1. Clenching or grinding at night (bruxism). throat. 2. Looseness and or soreness of back teeth. 7. Feeling of foreign object in throat.