Transcript of an Audio Interview with Professor Salima Hashmi (SH) Conducted by AAA Project Researcher Samina Iqbal (SI) on 23 M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smiles, Sweets and Flags Pakistanis Celebrate Country's 71St Birthday

Volume VIII, Issue-8,August 2018 August in History Smiles, sweets and flags Pakistanis celebrate country's 71st birthday August 14, 1947: Pakistan came ment functionaries and armed into existence. forces' officials took part. August 21, 1952: Pakistan and Schools and colleges also organised India agree on the boundary pact functions for students, and a rally between East Bengal & West Bengal. was held in the capital to mark August 22, 1952: A 24 hour Independence Day. telegraph telephone service is established between East Pakistan Border security forces both on the and West Pakistan. Indian side at Wagah, and the August 16, 1952: Kashmir Afghan side at Torkham exchanged Martyrs' Day observed throughout sweets and greetings with each Pakistan. other as a gesture of goodwill. August 7, 1954: Government of Pakistan approves the National President Mamnoon Hussain and Smiles are everywhere and the official functions and ceremonies a Anthem, written by Abul Asar caretaker PM Nasirul Mulk issued atmosphere crackles with 31-gun salute in the capital and Hafeez Jullundhri and composed by separate messages addressing the excitement as Pakistanis across the 21-gun salutes in the provincial Ahmed G. Chagla. nation on August 14. country celebrate their nation's 71st capitals, as well as a major event in August 17, 1954: Pakistan defeats Courtesy: Dawn anniversary of independence. Islamabad in which top govern - England by 24 runs at Oval during its maiden tour of England. Major cities have been decked out August 1, 1960: Islamabad is in bright, colourful lights, creating declared the principal seat of the a cheery and festive atmosphere. -

Sindh Police Shaheed List

List of Shuhada of Sindh Police since 1942 to 2014 Date of Ser # Rank No. NAME Father Name Surname DSTT: Shahadat 1 IP K/1296 Ghazanfar Kazmi Syed Sarwar Ali Syed Kazmi South, Karachi 13.08.2014 2 PC 11049 Muhammad Siddiq Zer Muhammad Court Police 18.12.2013 3 PC 188 PC/188 Muhammad Khalid Muhammad Siddique Arain SBA, District 07.06.2014 4 HC 20296 HC/20296 Zulfqar Ali Unar s/o M Sachal Muhammad Sachal Unar Crime Br. Sukkur 29.07.2014 5 HC 17989 HC/17989 Haji Wakeel Ali Khair Muhammad West Karachi 17.08.2014 6 HC 13848 HC/ 13848 Tahir Mehmood Muhammad Aslam SRP-1, Karachi 19.08.2014 7 HC 19323 HC/19323 Azhar Abbas Muhammad Shafi Malir, Karachi 19.08.2014 8 PC 19386 PC/19386 Muhammad Azam Mir Muhammad Malir, Karachi 19.08.2014 9 PC 24318 PC/24318 Junaid Akbar Javed Akbar West Karachi 27.08.2014 10 PC 18442 PC/18442 Lutufullah Charann Muhammad Waris Charann Malir, Karachi 29.08.2014 11 ASI ASI Jamil Ahmed Babar Haji Ali Nawaz Babar Jamshoro 03.09.2014 12 HC 9636 HC/9636 Yousuf Khan Khushhal Khan Security-II 04.09.2014 13 SI K-5431 SI (K-5431) Ghulam Sarwar Gulsher Ali Central, Karachi 16.09.2014 14 PC 14491 PC/14491 Aijaz Ahmed Niaz Ahmed Central, Karachi 16.09.2014 15 HC 41 HC/41 Bashir Qureshi Allah Rakhio Qureshi Jamshoro 19.09.2014 16 PC 247 PC/247 Ameer Ali Junejo Roshan Ali Junejo Larkana 22.09.2014 17 PC 16150 PC/16150 Muhammad Tahir Farooq Muhammad Alam Central, Karachi 23.09.2014 18 DPC 18908 DPC/18908 Waqar Hashmi Shafiq Hashmi Hashmi Muhafiz Force, Karachi 16.10.2014 19 ASI K-2272 ASI/ K-2272 Qalandar Bux Malhan Khan Chandio -

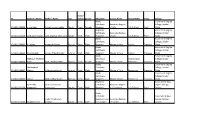

Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.No Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID

Details of Employees (Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID Women Medical 1 Dr. Afroze Khan Muhammad Chang (NULL) (NULL) Officer Women Medical 2 Dr. Shahnaz Abdullah Memon (NULL) 4130137928800 (NULL) Officer Muhammad Yaqoob Lund Women Medical 3 Dr. Saira Parveen (NULL) 4130379142244 (NULL) Baloch Officer Women Medical 4 Dr. Sharmeen Ashfaque Ashfaque Ahmed (NULL) 4140586538660 (NULL) Officer 5 Sameera Haider Ali Haider Jalbani Counselor (NULL) 4230152125668 214483656 Women Medical 6 Dr. Kanwal Gul Pirbho Mal Tarbani (NULL) 4320303150438 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 7 Dr. Saiqa Parveen Nizamuddin Khoso (NULL) 432068166602- (NULL) Officer Tertiary Care Manager 8 Faiz Ali Mangi Muhammad Achar (NULL) 4330213367251 214483652 /Medical Officer Women Medical 9 Dr. Kaneez Kalsoom Ghulam Hussain Dobal (NULL) 4410190742003 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 10 Dr. Sheeza Khan Muhammad Shahid Khan Pathan (NULL) 4420445717090 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 11 Dr. Rukhsana Khatoon Muhammad Alam Metlo (NULL) 4520492840334 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 12 Dr. Andleeb Liaqat Ali Arain (NULL) 454023016900 (NULL) Officer Badin S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID 1 MUHAMMAD SHAFI ABDULLAH WATER MAN unknown 1350353237435 10334485 2 IQBAL AHMED MEMON ALI MUHMMED MEMON Senior Medical Officer unknown 4110101265785 10337156 3 MENZOOR AHMED ABDUL REHAMN MEMON Medical Officer unknown 4110101388725 10337138 4 ALLAH BUX ABDUL KARIM Dispensor unknown -

South Asia Program

SOUTH ASIA PROGRAM 2018 BULLETIN Ali Kazim (Pakistan), Lover’s Temple Ruins (2018). Site-specific installation in Lawrence Gardens, Lahore TABLE OF CONTENTS FEATURES 2 TRANSITIONS 28 Are You Even Indian? ANNOUNCEMENTS 29 Island Country, Global Issues The Sri Lankan Vernacular The First Lahore Biennale Tilism Rohingya Refugee camps Chai and Chat 170 Uris Hall NEWS 10 50 Years of IARD Cornell University President Pollack visits India Ithaca, New York 14853-7601 ACHIEVEMENTS 32 Embodied Belongings Phone: 607-255-8923 Faculty Publications Sri Lanka Graduate Conference Fax: 607-254-5000 TCI scholars Urban South Asia Writ Small [email protected] FLAS fellows South Asian Studies Fellowships Recently Graduated Students Iftikhar Dadi, Director EVENTS 17 Visiting Scholars Phone: 607-255-8909 Writing Myself into the Diaspora [email protected] Arts Recaps SAP Seminars & Events Daniel Bass, Manager Phone: 607-255-8923 OUTREACH 22 [email protected] Going Global Global Impacts of Climate Change sap.einaudi.cornell.edu UPCOMING EVENTS 26 Tagore Lecture South Asian Studies Fellows Ali Kazim (detail) From the Director Iftikhar Dadi uring the 2017-2018 generously supported by the United I express deep appreciation to academic year, the South States Department of Education under Professor Anne Blackburn for her strong Asia Program (SAP) the Title VI program. The Cornell and leadership, vision, and commitment mounted a full program Syracuse consortium constitutes one of to SAP during her tenure as director of talks and lectures, only eight National Resource Centers during the past five years. The Program hosted international for the study of South Asia. I am very has developed many new initiatives Dscholars and artists, and supported pleased to note that our application under her able guidance, including the faculty and student research. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

ID Student's Name Father's Name Fresh

Fresh/ ID Student's Name Father's Name Type Failure gender Objection Course Name Group Name Value College Marks Goverment Degree Certificate Associate Degree College, Bozdar KD-0821-00600 dua e zahra parvez ahmed mallah Regular Fresh Female Required of Arts A.D.A (Pass) Part-I Wada Elligibility Goverment Degree Certificate Associate Degree College, Bozdar QP-0821-02420 syed zarar hussain syed ali gohar shah syed Regular Fresh Male Required of Arts A.D.A (Pass) Part-I Wada Marks Goverment Degree Certificate College, Bozdar KD-0821-00883 Ali Abbas Anwar Ali Bozdar External Fresh Male Required Master of Arts English Previous Wada Marks Goverment Degree Certificate College, Bozdar KD-0821-00884 Ghulam Qadir parvez Ahmed Bozdar External Fresh Male Required Master of Arts English Previous Wada Marks Goverment Degree Mehwish RAsheed Certificate International College, Bozdar KD-0821-00890 Khan Abdul Rasheed Khan External Fresh Female Required Master of Arts Relations Previous Wada Marks Goverment Degree Muhammad Certificate College, Bozdar KD-0821-00887 Mohsin Muhammad amin External Fresh Male Required Master of Arts Economics Previous Wada Marks Goverment Degree Certificate College, Bozdar KD-0821-00886 sumair Abdul Sattar Shaikh External Fresh Male Required Master of Arts Economics Previous Wada Elligibility Government Boys syed talha syed muhammad Certificate Associate Degree Degree College, QP-0821-02360 mehmood mehmood Regular Fresh Male Required of Commerce A.D.C (Pass) Part-I Daharki Marks Certificate Government Boys muhammad aslam Required, -

Alhamra Arts Council Lahore, Pakistan

The Aga Khan Award for Architecture Alhamra Arts Council Lahore, Pakistan Architect: Nayyar Ali Dada Lahore, Pakistan Client: Lahore Arts Council Lahore, Pakistan Date of Completion: 1992 0405.PAK Table of Contents Technical Review Summary (37 pages) Feature from the 1998 Award Book (12 pages) 1998 Architect’s Record (5 pages) Nomination Forms (6 forms, 12 pages) Architect's Presentation Panels (16 pages) Images and Drawings (25 pages) Thumbnail Images of Scanned Slides (14 pages) List of Visual Materials (15 pages) List of Additional Materials (2 pages) Alhamra Arts Council, Lahore, Pakistan Alhamra Arts Council Lahore, Pakistan Acc No: S063738 VM Title: Date: 15.03.1983 Photographer: BETANT Jacques Copyright: Y Technical Infos: Notes: Location: C1 VM Link: 0405 Alhamra Arts Council Acc No: S063739 VM Title: Date: 15.03.1983 Photographer: BETANT Jacques Copyright: Y Technical Infos: Notes: Location: C1 VM Link: 0405 Alhamra Arts Council Acc No: S063754 VM Title: Date: 15.03.1983 Photographer: BETANT Jacques Copyright: Y Technical Infos: Notes: Location: C1 VM Link: 0405 Alhamra Arts Council Acc No: S063755 VM Title: Date: 15.03.1983 Photographer: BETANT Jacques Copyright: Y Technical Infos: Notes: Location: C1 VM Link: 0405 Alhamra Arts Council Acc No: S063760 VM Title: Date: 15.03.1983 Photographer: BETANT Jacques Copyright: Y Technical Infos: Notes: Location: C1 VM Link: 0405 Alhamra Arts Council Acc No: S063762 VM Title: Date: 15.03.1983 Photographer: BETANT Jacques Copyright: Y Technical Infos: Notes: Location: C1 VM Link: 0405 Alhamra -

Situation Analysis Union Council Bandhi, District Nawabshah

NRSP Situation Analysis of U n i o n C o u n c i l B a n d h i Taluka Daur District Nawabshah October 2009 Monitoring Evaluation & Research Section National Rural Support Programme Situation Analysis of U n i o n C o u n c i l B a n d h i Taluka Daurr, District Nawabshah October 2009 Monitoring Evaluation & Research Section National Rural Support Programme ii Table of Contents Background ..............................................................................................................2 Objectives ................................................................................................................2 Methodology .............................................................................................................2 Summary of Socio-Economic Findings ..............................................................3 Introduction to the Area ............................................................................................3 Demography .............................................................................................................4 Agriculture ................................................................................................................4 Farming and Landholding Pattern ............................................................................4 Livestock ..................................................................................................................5 Education & Health ..................................................................................................5 -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

Faizghar Newsletter

Issue: January Year: 2016 NEWSLETTER Content Faiz Ghar trip to Rana Luxury Resort .............................................. 3 Faiz International Festival ................................................................... 4 Children at FIF ............................................................................................. 11 Comments .................................................................................................... 13 Workshop on Thinking Skills ................................................................. 14 Capacity Building Training workshops at Faiz Ghar .................... 15 [Faiz Ghar Music Class tribute to Rasheed Attre .......................... 16 Faiz Ghar trip to [Rana Luxury Resort The Faiz Ghar yoga class visited the Rana Luxury Resort and Safari Park at Head Balloki on Sunday, 13th December, 2015. The trip started with live music on the tour bus by the Faiz Ghar music class. On reaching the venue, the group found a quiet spot and spread their yoga mats to attend a vigorous yoga session conducted by Yogi Sham- shad Haider. By the time the session ended, the cold had disappeared, and many had taken o their woollies. The time was ripe for a fruit eating session. The more sporty among the group started playing football and frisbee. By this time the musicians had got their act together. The live music and dance session that followed became livelier when a large group of school girls and their teachers joined in. After a lot of food for the soul, the group was ready to attack Gogay kay Chaney, home made koftas, organic salads, and the most delicious rabri kheer. The group then took a tour of the jungle and the safari park. They enjoyed the wonderful ambience of the bamboo jungle, and the ostriches, deers, parakeet, swans, and many other wild animals and birds. Some members also took rides on the train and colour- ful donkey carts. -

Samina Iqbal Art History Department Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia

Samina Iqbal Art History Department Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia AIPS Short Term Fellowship Report Grant Period: August 3rd – October 3rd, 2014 Location: Lahore and Islamabad The AIPS short-term fellowship grant enabled me to travel to Pakistan for two months this summer and conduct my dissertation research, which focuses on the Modern Art of Pakistan. More specifically, my research examines the modern trends in Pakistani art beginning in 1947 and the pivotal role of the five founding artists of Lahore Art Circle (LAC) in constructing modernist sensibilities and secular trends in Pakistani art from 1950-1957. LAC, founded in 1952 included artists: Ahmed Pervaiz (1926-1979), Ali Imam (1924-2002), Anwar Jalal Shemza (1928 -1985), Moyene Najmi (1926-1997), and Sheikh Safdar (1924-1983). Since my focus is on the first decade of Pakistani modern art after its independence, it is incredibly difficult to locate any archival material on this era especially in the field of Fine Arts. Locating the actual works of LAC artists, which are mostly in private collections, is the challenging task that I set for myself for the two-month research in Pakistan. I arrived in Lahore, intending to look at a few libraries for archival material and a few museums for actual works of arts. However, this research trip turned out to be extremely productive in finding and locating much more than I anticipated. I divided my research into three parts: a. I conducted a number of semiformal and informal interviews with art critics, friends and immediate family members of LAC artists. This included renowned writers such as Intizar Husain, Kishwar Naheed, Salima Hashmi, Nazish Attaullah, Quddus Mirza, Attiya Najmi, Shahnaz Imam, Anwar Saeed, Dr. -

Sindh Public Service Commission Thandi Sarak Hyderabad

SINDH PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION THANDI SARAK HYDERABAD NO.PSC/EXAM:(S.S)2017/30 Hyderabad: Dated: 05.06.2017 PRESS RELEASE The Sindh Public Service Commission interviewed eligible candidates for the post of Women Medical Officer BPS-17 in Health Department, Government of Sindh in the months of June, July, August, September & October 2016 and May 2017 and found the following candidates fit and suitable for appointment against the said post. WOMEN MEDICAL OFFICER BPS-17 MERIT ROLL RURAL / NAME OF CANDIDATE FATHER’S NAME NO. NO. URBAN 01 13097 Dr. Nuzhat Parveen D/o. Musurrat Hussain Urban 02 13804 Dr. Sumera Khan D/o. Muhammad Gulzar Khan Urban 03 12765 Dr. Lubna Aman D/o. Amanullah Urban 04 11966 Dr. Uzma Aslam D/o Mohammad Aslam Arain Rural 05 13274 Dr. Roshila Shamim D/o Shamim Ahmed Urban 06 14682 Dr. Rumana D/o. Panjal Khan Sangi Rural 07 14491 Dr. Nagina D/o Sahib Dino Shaikh Rural 08 10854 Dr. Mahrukh Shah D/o Syed Sharfuddin Shah Urban 09 10615 Dr. Hanna Naeem D/o Abdul Naeem Khan Rural 10 12545 Dr. Gul Anum D/o Muhammad Iqbal Urban 11 12699 Dr. Javeria Ashfaq D/o. Ashfaq Ahmed Urban 12 11663 Dr. Shafia Memon D/o Bashir Ahmed Rural 13 13372 Dr. Safia Shaikh D/o Gul Nawaz Urban 14 14555 Dr. Kanwal D/o. Abdul Razzak Khuhro Rural 15 13106 Dr. Paras Bachal D/o. Bachal Rural 16 12963 Dr. Nabiya Sandeelo D/o. Mohammad Aslam Sandeelo Rural 17 15195 Dr. Romana Pirah D/o Muhammad Nawaz Channa Urban 18 13302 Dr.