@Fernando De Araujo Prisoner of Conscience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Ori Inal Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 481 305 FL 027 837 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph, Ed. TITLE Voices from Phnom Penh. Development & Language: Global Influences & Local Effects. ISBN ISBN-1-876768-50-9 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 362p. AVAILABLE FROM Language Australia Ltd., GPO Box 372F, Melbourne VIC 3001, Australia ($40). Web site: http://languageaustralia.com.au/. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College School Cooperation; Community Development; Distance Education; Elementary Secondary Education; *English (Second Language); Ethnicity; Foreign Countries; Gender Issues; Higher Education; Indigenous Populations; Intercultural Communication; Language Usage; Language of Instruction; Literacy Education; Native Speakers; *Partnerships in Education; Preservice Teacher Education; Socioeconomic Status; Student Evaluation; Sustainable Development IDENTIFIERS Cambodia; China; East Timor; Language Policy; Laos; Malaysia; Open q^,-ity; Philippines; Self Monitoring; Sri Lanka; Sustainability; Vernacular Education; Vietnam ABSTRACT This collection of papers is based on the 5th International Conference on Language and Development: Defining the Role of Language in Development, held in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in 2001. The 25 papers include the following: (1) "Destitution, Wealth, and Cultural Contest: Language and Development Connections" (Joseph Lo Bianco); (2) "English and East Timor" (Roslyn Appleby); (3) "Partnership in Initial Teacher Education" (Bao Kham and Phan Thi Bich Ngoc); (4) "Indigenous -

Tuberculosis – R-GLC Mission Report: 2018

Tuberculosis – r-GLC Mission Report: 2018 Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Dr Malik M Parmar (MD), National Professional Officer – Drug Resistant TB, WHO Country Office for India, New Delhi 8/31/2018 Regional Advisory Committee on MDR-TB SEAR (r-GLC) Secretariat WHO South East Asia Regional Office Tuberculosis – r-GLC Mission Report: 2018 2018 Regional Advisory Committee on MDR-TB SEAR (r-GLC) Secretariat WHO South East Asia Regional Office TB r-GLC MISSION REPORT 2018 Programme: Country: Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Lead implementing agency: National Tuberculosis Programme, Ministry of Health, Government of Timor-Leste Inclusive dates of mission: 27th - 30th August 2018 Author: Dr Malik M Parmar, National Professional Officer – Drug Resistant TB, WHO Country Office for India, New Delhi Acknowledgments: Ministry of Health, Government of Timor-Leste, Dili National TB Programme, Government of Timor-Leste, Dili WHO Timor-Leste, Dili and India, New Delhi WHO South East Asia Regional Office, New Delhi Dr S Anand, WHO-RNTCP National Consultant TB Labs, New Delhi 1 Tuberculosis – r-GLC Mission Report: 2018 2018 Contents Acknowledgments: ............................................................................................................... 3 Abbreviations and acronyms: ............................................................................................ 4 I. Executive summary: ...................................................................................................... 6 Findings/Observation......................................................................................................... -

Turkish President Turgut Özal's Impact on Nursultan

TURKISH PRESIDENT TURGUT ÖZAL’S IMPACT ON NURSULTAN NAZARBAYEV’S PERCEPTION OF TURKEY* Nursultan Nazarbayev'ın Türkiye Algısına Tugut Özal'ın Etkisi Din Muhammed AMETBEK** Abstract Nursultan Nazarbayev as the founding President of Kazakhstan played a determinant role in the formation of Kazakh foreign policy. In this respect, the article examines Nazarbayev’s perception of Turkey as a decision maker in foreign policy are based on observation rather than realities. Nazarbayev is aware of the fact that the national identity of Kazakhstan is divided between two competing poles; Russian and Kazakh, in a broader sense; Slavic and Turkic. From this perspective, Nazarbayev’s perception of Turkey is significant as it is not only related to foreign policy but at the same time the national identity of Kazakhstan. The study argues that the President of Republic of Turkey of early 1990s Turgut Özal with his active diplomacy towards Kazakhstan contributed to the positive image of Turkey. The research concludes that close and reliable relations between Nazarbayev and Özal became the basis of a strategic part- nership between Kazakhstan and Turkey. Keywords: Turgut Özal, Nursultan Nazarbayev, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Perception, National Identity Özet Kazakistan’ın kurucu Cumhurbaşkanı Nursultan Nazarbayev’in, Kazak dış politi- kasının oluşumunda belirleyici rol üstlendiği kesindir. Bu bağlamda, makale, Nazarba- yev’in Türkiye algısını ele almaktadır. Çünkü inşacı ekolün iddiasına dış politika kararları gerçeklere değil algı üzerine alınmaktadır. Nazarbayev Kazakistan’ın ulusal kimliğinin Rus ve Kazak olarak, daha geniş kapsamda Slav ve Türk olarak yarışan iki kutba ayrıldığının farkındadır. Buradan hareketle, Nazarbayev’in Türkiye algısı, yal- nızca dış politika açısından değil aynı zamanda Kazakistan’ın ulusal kimliği açısından da önemlidir. -

Indonesia: Travel Advice MANILA

Indonesia: Travel Advice MANILA B M U M KRUNG THEP A R (BANGKOK) CAMBODIA N M T International Boundary A E Medan I PHNOM PENH V Administrative Boundary 0 10 miles Andaman National Capital 0 20 km Sea T Administrative Centre H South A SUMATERA PHILIPPINES Other Town I L UTARA A Major Road N D China Sea MELEKEOKRailway 0 200 400 miles Banda Aceh Mount Sinabung 0 600 kilometres BANDAR SERI BEGAWAN A Langsa BRUNEI I ACEH MALAYSIA S Celebes Medan Y KALIMANTAN A Tarakan KUALA LUMPUR UTARA Pematangsiantar L Tanjung Selor SeaSULAWESI A UTARA PACIFIC SUMATERA M Tanjungredeb GORONTALO Dumai UTARA SINGAPORE Manado SINGAPORE Tolitoli Padangsidempuan Tanjungpinang Sofifi RIAU Pekanbaru KALIMANTAN OCEAN Nias Singkawang TIMUR KEPULAUAN Pontianak Gorontalo Sumatera RIAU Borneo Payakumbuh KALIMANTAN Samarinda SULAWESI Labuha Manokwari Padang (Sumatra) BARAT TENGAH KEPULAUAN Palu MALUKU Sorong SUMATERA Jambi BANGKA BELITUNG KALIMANTAN Maluku Siberut Balikpapan UTARA PAPUA BARAT TENGAH Sulawesi BARAT JAMBI Pangkalpinang Palangkaraya SULAWESI Sungaipenuh Ketapang BARAT Bobong (Moluccas) Jayapura SUMATERA Sampit (Celebes) SELATAN KALIMANTAN Mamuju Namlea Palembang SELATAN Seram Bula Lahat Prabumulih Banjarmasin Majene Bengkulu Kendari Ambon PAPUA Watampone BENGKULU LAMPUNG INDONESIA Bandar JAKARTA Java Sea Makassar New Lampung JAKARTA SULAWESI Banda JAWA TENGAH SULAWESI MALUKU Guinea Serang JAWA TIMUR SELATAN TENGGARA Semarang Kepulauan J Sumenep Sea Aru PAPUA BANTEN Bandung a w a PAPUA ( J a v Surabaya JAWA a ) NUSA TENGGARA Lumajang BALI BARAT Kepulauan -

Countries and Their Capital Cities Cheat Sheet by Spaceduck (Spaceduck) Via Cheatography.Com/4/Cs/56

Countries and their Capital Cities Cheat Sheet by SpaceDuck (SpaceDuck) via cheatography.com/4/cs/56/ Countries and their Captial Cities Countries and their Captial Cities (cont) Countries and their Captial Cities (cont) Afghani stan Kabul Canada Ottawa Federated States of Palikir Albania Tirana Cape Verde Praia Micronesia Algeria Algiers Cayman Islands George Fiji Suva American Samoa Pago Pago Town Finland Helsinki Andorra Andorra la Vella Central African Republic Bangui France Paris Angola Luanda Chad N'Djamena French Polynesia Papeete Anguilla The Valley Chile Santiago Gabon Libreville Antigua and Barbuda St. John's Christmas Island Flying Fish Gambia Banjul Cove Argentina Buenos Aires Georgia Tbilisi Cocos (Keeling) Islands West Island Armenia Yerevan Germany Berlin Colombia Bogotá Aruba Oranjestad Ghana Accra Comoros Moroni Australia Canberra Gibraltar Gibraltar Cook Islands Avarua Austria Vienna Greece Athens Costa Rica San José Azerbaijan Baku Greenland Nuuk Côte d'Ivoire Yamous‐ Bahamas Nassau Grenada St. George's soukro Bahrain Manama Guam Hagåtña Croatia Zagreb Bangladesh Dhaka Guatemala Guatemala Cuba Havana City Barbados Bridgetown Cyprus Nicosia Guernsey St. Peter Port Belarus Minsk Czech Republic Prague Guinea Conakry Belgium Brussels Democratic Republic of the Kinshasa Guinea- Bissau Bissau Belize Belmopan Congo Guyana Georgetown Benin Porto-Novo Denmark Copenhagen Haiti Port-au -P‐ Bermuda Hamilton Djibouti Djibouti rince Bhutan Thimphu Dominica Roseau Honduras Tegucig alpa Bolivia Sucre Dominican Republic Santo -

Bayu-Undan No Timor-Leste Servisu Hamutuk Ba Dezenvolvimentu

Bayu-Undan no Timor-Leste Servisu hamutuk ba Dezenvolvimentu Maiu 2015 Bayu-Undan kontinua hetan di’ak hosi Timoroan sira nia partisipasaun Elementu xave ida ne’e be kontinua nafatin ba atividade Bayu-Undan sira involve entrega planus Kapasidade Lokál hodi fó empregu no formasaun prosionál ba Timoroan no rezidente permanente sira, ho objetivu atu hadi’ak koñesimentu no harii kapasidade ho nasaun. ENJEÑEIRU TIMOROAN SIRA IHA DALAN SEMO MENON NARUK Fornesedór servisus elikópteru CHC CONOCOPHILLIPS nian fó formasaun prosionál nafatin ba empregadu Timor-Leste sira. Foin daudaun ne’e enjeñeiru nain tolu manutensaun aeronave tama iha kursu semana neen ida ne’e be foka manutensaun ba aviaun tipu AS332. Konkluzaun kursu ne’e hakat importante ida tan iha sira nia dalan atu sai enjeñeirus lisensiadus hosi Autoridade ba Seguransa Aviasaun Sivil(ASAS) iha maizumenus tinan HOSI karukt: Atoy (Antonio Jonando Vicente rua. Souza), Elvis (Elves Tilman Da Cruz Soares) no Tito (Tito Manuel Exposto) DISTRIBUIDÓR TIMOROAN SIRA ASISTE SESAUN INFORMASAUN HOSI BAYUUNDAN Sesaun informasaun no osina administrasaun balu tuir hosi distribuidór Timoroan sira tulun informa estudu ida hosi ConocoPhillips ho objetivu atu aumenta kapasidade lokál. Ema liu 120 mak tuir sesaun no osina administrasaun sira ne’e hala’o iha Dili, ne’e be distribuidór lokál sira bele simu informasaun no diskute kapasidade indústria nian diretamente ho reprezentante Cono- coPhillips nian sira. Distribuidór Timor-Leste sira halibur malu iha Dili atu rona diretamente kona-ba esforsu ConocoPhillips atu aumenta oportunidade kapasidade lokál ConocoPhillips halo daudaun estudu fornesimentu iha Timor-Leste, ho apoiu hosi Worley Parsons. Estudu ne’e sei fó-hatene ba kompañia, hanesan Operadór, kapasidade ne’ ebe iha ona no potensiál iha Timor-Leste atu apoia liuliu rekizitus Bayu-Undan nian ba material no servisus. -

Global Epidemiology of Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI)

Current Hepatology Reports (2019) 18:274–279 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-019-00475-z DRUG-INDUCED LIVER INJURY (P HAYASHI, SECTION EDITOR) Global Epidemiology of Drug-Induced Liver Injury (DILI) Einar S. Björnsson1,2,3 Published online: 16 July 2019 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose of Review Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is not an uncommon liver disease in many parts of the world. DILI is one of the most common causes of acute liver failure in most countries. The current review summarizes the global epidemiology of DILI. Recent Findings The number need to harm in terms of DILI due to amoxicillin-clavulanate was approximately 1 out 2300, but was higher for azathioprine (1 out of 133) and infliximab (1 out of 148). A retrospective Chinese study showed the highest rate of DILI in hospitalized patients with an incidence of approximately 24 patients per 100,000 annually with a more favorable prognosis in the DILI cohort than previously reported from Europe, the USA, and Asia. Summary Although large DILI registries from Europe and the USA have collected much data, more prospective studies with continual enrollment are needed particularly as new therapies such as immune modulatory and oncological medications with longer half-lives and latencies come to market. Keywords DILI . Hepatotoxicity . Epidemiology . Incidence . Prognosis . Global Introduction performed. Two in Europe and one recently in the USA are notable [13, 14, 15•]. Hepatotoxicity, drug-induced liver injury (DILI), and adverse With growing registry and cohort data, some recurring liver reactions are terms used interchangeably. -

Dili Bulletin: About ADB Country Partnership Strategies

October 2011 Edition No. 4 www.adb.org/Timor-Leste About ADB Country Project Milestones The government signed contracts in September 2011 Partnership Strategies to rehabilitate the Liquica–Maubara section of the national road network and to maintain the Maliana– Country partnership strategies (CPSs) are the Asian Batugarde section. The government also issued a Development Bank’s (ADB) primary platform for designing tender for rehabilitation of the Loes–Batugarde operations to deliver development results at the country section. An existing ADB grant will fund most of the level. The CPS ensures ADB country operations align with works. government development priorities, reflect ADB’s core A contract was issued by the government in areas of specialization, and complement the work of other September 2011 for the rehabilitation of the water development partners. system in three subzones of Dili. The works will be The CPS cycle mirrors the government’s own strategic largely funded by an existing ADB grant. planning cycle (as summarized in the figure overleaf). This The government and ADB signed a grant in October enhances synergies and reduces transaction costs for the 2011 worth $11 million to improve the safety and government and other stakeholders. quality of drinking water in the district capitals of The country operations business plan is a key Manatuto and Pante Macasar. Upon completion, the component of the CPS cycle. Based on the CPS, this plan is rehabilitated water supply systems will provide clean updated annually to provide a 3‐year rolling pipeline of water to about 30,500 people. The grant will also help activities and the resources needed to support them. -

Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED)

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 9/13/2021 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan FMO Inna Rotenberg ICASS Chair CDR David Millner IMO Cem Asci KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ISO Aaron Smith Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: https://af.usembassy.gov/ Algeria Officer Name DCM OMS Melisa Woolfolk ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- ALT DIR Tina Dooley-Jones 2000, Fax +213 (23) 47-1781, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, CM OMS Bonnie Anglov Website: https://dz.usembassy.gov/ Co-CLO Lilliana Gonzalez Officer Name FM Michael Itinger DCM OMS Allie Hutton HRO Geoff Nyhart FCS Michele Smith INL Patrick Tanimura FM David Treleaven LEGAT James Bolden HRO TDY Ellen Langston MGT Ben Dille MGT Kristin Rockwood POL/ECON Richard Reiter MLO/ODC Andrew Bergman SDO/DATT COL Erik Bauer POL/ECON Roselyn Ramos TREAS Julie Malec SDO/DATT Christopher D'Amico AMB Chargé Ross L Wilson AMB Chargé Gautam Rana CG Ben Ousley Naseman CON Jeffrey Gringer DCM Ian McCary DCM Acting DCM Eric Barbee PAO Daniel Mattern PAO Eric Barbee GSO GSO William Hunt GSO TDY Neil Richter RSO Fernando Matus RSO Gregg Geerdes CLO Christine Peterson AGR Justina Torry DEA Edward (Joe) Kipp CLO Ikram McRiffey FMO Maureen Danzot FMO Aamer Khan IMO Jaime Scarpatti ICASS Chair Jeffrey Gringer IMO Daniel Sweet Albania Angola TIRANA (E) Rruga Stavro Vinjau 14, +355-4-224-7285, Fax +355-4- 223-2222, Workweek: Monday-Friday, 8:00am-4:30 pm. -

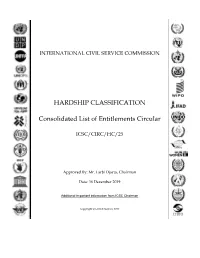

HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular

INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION HARDSHIP CLASSIFICATION Consolidated List of Entitlements Circular ICSC/CIRC/HC/25 Approved By: Mr. Larbi Djacta, Chairman Date: 16 December 2019 Additional important information from ICSC Chairman Copyright © United Nations 2017 United Nations International Civil Service Commission (HRPD) Consolidated list of entitlements - Effective 1 January 2020 Country/Area Name Duty Station Review Date Eff. Date Class Duty Station ID AFGHANISTAN Bamyan 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG002 AFGHANISTAN Faizabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG003 AFGHANISTAN Gardez 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG018 AFGHANISTAN Herat 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG007 AFGHANISTAN Jalalabad 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG008 AFGHANISTAN Kabul 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG001 AFGHANISTAN Kandahar 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG009 AFGHANISTAN Khowst 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 E AFG010 AFGHANISTAN Kunduz 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG020 AFGHANISTAN Maymana (Faryab) 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG017 AFGHANISTAN Mazar-I-Sharif 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG011 AFGHANISTAN Pul-i-Kumri 01/Jan/2020 01/Jan/2020 E AFG032 ALBANIA Tirana 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ALB001 ALGERIA Algiers 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ALG001 ALGERIA Tindouf 01/Jan/2018 01/Jan/2018 E ALG015 ALGERIA Tlemcen 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 C ALG037 ANGOLA Dundo 01/Jul/2018 01/Jul/2018 D ANG047 ANGOLA Luanda 01/Jul/2018 01/Jan/2018 B ANG001 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA St. Johns 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ANT010 ARGENTINA Buenos Aires 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 A ARG001 ARMENIA Yerevan 01/Jan/2019 01/Jan/2019 -

Tragedy in East Timor

TRAGEDY IN EAST TIMOR Report on the Trials in Dili and Jakarta International Commission of Jurists Geneva, Switzerland The ICJ permits free reproduction of extracts from any of its publications provided that due acknowledgement is given and a copy of the publication carrying the extract is sent to its headquarters at the following address: P.O. Box 160, CH -1216 Cointrin, Geneva, Switzerland. Copyright ©, International Commission of Jurists, 1992 ISBN 92 9037 062 9 TRAGEDY IN EAST TIMOR Report on the Trials in Dili and Jakarta International Commission of Jurists (IC'J) Geneva, Switzerland J U W -#-sv ti'r > | ^ I International Commission of Jurists Geneva, Switzerland CONTENTS Abbreviations and terms ................................................................................9 P re fac e ............................................................................................................... 11 Introduction ...................................................................................................13 Integration and Self-Determination ......................................................... 13 The Role of the A rm y ..................................................................................18 The Gadjah Mada S tu d y ............................................................................. 21 Human Rights Violations Prior to 12 November 1991..................................................................... 22 The Events of 12 November 1991..............................................................23 -

KOMUNITAS ADAT MUARA TAE Indonesia

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. KOMUNITAS ADAT MUARA TAE Indonesia Equator Initiative Case Studies Local sustainable development solutions for people, nature, and resilient communities UNDP EQUATOR INITIATIVE CASE STUDY SERIES Local and indigenous communities across the world are 126 countries, the winners were recognized for their advancing innovative sustainable development solutions achievements at a prize ceremony held in conjunction that work for people and for nature. Few publications with the United Nations Convention on Climate Change or case studies tell the full story of how such initiatives (COP21) in Paris. Special emphasis was placed on the evolve, the breadth of their impacts, or how they change protection, restoration, and sustainable management over time. Fewer still have undertaken to tell these stories of forests; securing and protecting rights to communal with community practitioners themselves guiding the lands, territories, and natural resources; community- narrative. The Equator Initiative aims to fill that gap. based adaptation to climate change; and activism for The Equator Initiative, supported by generous funding environmental justice. The following case study is one in from the Government of Norway, awarded the Equator a growing series that describes vetted and peer-reviewed Prize 2015 to 21 outstanding local community and best practices intended to inspire the policy dialogue indigenous peoples initiatives to reduce poverty, protect needed to take local success to scale, to improve the global nature, and