TFEB Links MYC Signaling to Epigenetic Control of Myeloid Differentiation and Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise and Fall of the Bovine Corpus Luteum

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC Theses & Dissertations Graduate Studies Spring 5-6-2017 The Rise and Fall of the Bovine Corpus Luteum Heather Talbott University of Nebraska Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd Part of the Biochemistry Commons, Molecular Biology Commons, and the Obstetrics and Gynecology Commons Recommended Citation Talbott, Heather, "The Rise and Fall of the Bovine Corpus Luteum" (2017). Theses & Dissertations. 207. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd/207 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE BOVINE CORPUS LUTEUM by Heather Talbott A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the University of Nebraska Graduate College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Graduate Program Under the Supervision of Professor John S. Davis University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, Nebraska May, 2017 Supervisory Committee: Carol A. Casey, Ph.D. Andrea S. Cupp, Ph.D. Parmender P. Mehta, Ph.D. Justin L. Mott, Ph.D. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation was supported by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Pre-doctoral award; University of Nebraska Medical Center Graduate Student Assistantship; University of Nebraska Medical Center Exceptional Incoming Graduate Student Award; the VA Nebraska-Western Iowa Health Care System Department of Veterans Affairs; and The Olson Center for Women’s Health, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nebraska Medical Center. -

Implications in Parkinson's Disease

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Lysosomal Ceramide Metabolism Disorders: Implications in Parkinson’s Disease Silvia Paciotti 1,2 , Elisabetta Albi 3 , Lucilla Parnetti 1 and Tommaso Beccari 3,* 1 Laboratory of Clinical Neurochemistry, Department of Medicine, University of Perugia, Sant’Andrea delle Fratte, 06132 Perugia, Italy; [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (L.P.) 2 Section of Physiology and Biochemistry, Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Perugia, Sant’Andrea delle Fratte, 06132 Perugia, Italy 3 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Perugia, Via Fabretti, 06123 Perugia, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 January 2020; Accepted: 20 February 2020; Published: 21 February 2020 Abstract: Ceramides are a family of bioactive lipids belonging to the class of sphingolipids. Sphingolipidoses are a group of inherited genetic diseases characterized by the unmetabolized sphingolipids and the consequent reduction of ceramide pool in lysosomes. Sphingolipidoses include several disorders as Sandhoff disease, Fabry disease, Gaucher disease, metachromatic leukodystrophy, Krabbe disease, Niemann Pick disease, Farber disease, and GM2 gangliosidosis. In sphingolipidosis, lysosomal lipid storage occurs in both the central nervous system and visceral tissues, and central nervous system pathology is a common hallmark for all of them. Parkinson’s disease, the most common neurodegenerative movement disorder, is characterized by the accumulation and aggregation of misfolded α-synuclein that seem associated to some lysosomal disorders, in particular Gaucher disease. This review provides evidence into the role of ceramide metabolism in the pathophysiology of lysosomes, highlighting the more recent findings on its involvement in Parkinson’s disease. Keywords: ceramide metabolism; Parkinson’s disease; α-synuclein; GBA; GLA; HEX A-B; GALC; ASAH1; SMPD1; ARSA * Correspondence [email protected] 1. -

Defining Functional Interactions During Biogenesis of Epithelial Junctions

ARTICLE Received 11 Dec 2015 | Accepted 13 Oct 2016 | Published 6 Dec 2016 | Updated 5 Jan 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms13542 OPEN Defining functional interactions during biogenesis of epithelial junctions J.C. Erasmus1,*, S. Bruche1,*,w, L. Pizarro1,2,*, N. Maimari1,3,*, T. Poggioli1,w, C. Tomlinson4,J.Lees5, I. Zalivina1,w, A. Wheeler1,w, A. Alberts6, A. Russo2 & V.M.M. Braga1 In spite of extensive recent progress, a comprehensive understanding of how actin cytoskeleton remodelling supports stable junctions remains to be established. Here we design a platform that integrates actin functions with optimized phenotypic clustering and identify new cytoskeletal proteins, their functional hierarchy and pathways that modulate E-cadherin adhesion. Depletion of EEF1A, an actin bundling protein, increases E-cadherin levels at junctions without a corresponding reinforcement of cell–cell contacts. This unexpected result reflects a more dynamic and mobile junctional actin in EEF1A-depleted cells. A partner for EEF1A in cadherin contact maintenance is the formin DIAPH2, which interacts with EEF1A. In contrast, depletion of either the endocytic regulator TRIP10 or the Rho GTPase activator VAV2 reduces E-cadherin levels at junctions. TRIP10 binds to and requires VAV2 function for its junctional localization. Overall, we present new conceptual insights on junction stabilization, which integrate known and novel pathways with impact for epithelial morphogenesis, homeostasis and diseases. 1 National Heart and Lung Institute, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 2 Computing Department, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 3 Bioengineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 4 Department of Surgery & Cancer, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Understanding the Molecular Pathobiology of Acid Ceramidase Deficiency

Understanding the Molecular Pathobiology of Acid Ceramidase Deficiency By Fabian Yu A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto © Copyright by Fabian PS Yu 2018 Understanding the Molecular Pathobiology of Acid Ceramidase Deficiency Fabian Yu Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto 2018 Abstract Farber disease (FD) is a devastating Lysosomal Storage Disorder (LSD) caused by mutations in ASAH1, resulting in acid ceramidase (ACDase) deficiency. ACDase deficiency manifests along a broad spectrum but in its classical form patients die during early childhood. Due to the scarcity of cases FD has largely been understudied. To circumvent this, our lab previously generated a mouse model that recapitulates FD. In some case reports, patients have shown signs of visceral involvement, retinopathy and respiratory distress that may lead to death. Beyond superficial descriptions in case reports, there have been no in-depth studies performed to address these conditions. To improve the understanding of FD and gain insights for evaluating future therapies, we performed comprehensive studies on the ACDase deficient mouse. In the visual system, we reported presence of progressive uveitis. Further tests revealed cellular infiltration, lipid buildup and extensive retinal pathology. Mice developed retinal dysplasia, impaired retinal response and decreased visual acuity. Within the pulmonary system, lung function tests revealed a decrease in lung compliance. Mice developed chronic lung injury that was contributed by cellular recruitment, and vascular leakage. Additionally, we report impairment to lipid homeostasis in the lungs. ii To understand the liver involvement in FD, we characterized the pathology and performed transcriptome analysis to identify gene and pathway changes. -

Down Regulation of Membrane-Bound Neu3 Constitutes a New

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Publications of the IAS Fellows IJC International Journal of Cancer Down regulation of membrane-bound Neu3 constitutes a new potential marker for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and induces apoptosis suppression of neoplastic cells Chandan Mandal1, Cristina Tringali2, Susmita Mondal1, Luigi Anastasia2, Sarmila Chandra3, Bruno Venerando2 and Chitra Mandal1 1 Infectious Diseases and Immunology Division, Indian Institute of Chemical Biology, A Unit of Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Govt of India, 4, Raja S. C. Mullick Road, Kolkata 700032, India 2 Department of Medical Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biotechnology, University of Milan, and IRCCS Policlinico San Donato, San Donato, Milan, Italy 3 Department of Hematology, Kothari Medical Centre, Kolkata 700027, India Membrane-linked sialidase Neu3 is a key enzyme for the extralysosomal catabolism of gangliosides. In this respect, it regulates pivotal cell surface events, including trans-membrane signaling, and plays an essential role in carcinogenesis. In this report, we demonstrated that acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), lymphoblasts (primary cells from patients and cell lines) are characterized by a marked down-regulation of Neu3 in terms of both gene expression (230 to 40%) and enzymatic activity toward ganglioside GD1a (225.6 to 30.6%), when compared with cells from healthy controls. Induced overexpression of Neu3 in the ALL-cell line, MOLT-4, led to a significant increase of ceramide (166%) and to a parallel decrease of lactosylceramide (255%). These events strongly guided lymphoblasts to apoptosis, as we assessed by the decrease in Bcl2/ Bax ratio, the accumulation of Neu3 transfected cells in the sub G0–G1 phase of the cell cycle, the enhanced annexin-V positivity, the higher cleavage of procaspase-3. -

Predicting Coupling Probabilities of G-Protein Coupled Receptors Gurdeep Singh1,2,†, Asuka Inoue3,*,†, J

Published online 30 May 2019 Nucleic Acids Research, 2019, Vol. 47, Web Server issue W395–W401 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz392 PRECOG: PREdicting COupling probabilities of G-protein coupled receptors Gurdeep Singh1,2,†, Asuka Inoue3,*,†, J. Silvio Gutkind4, Robert B. Russell1,2,* and Francesco Raimondi1,2,* 1CellNetworks, Bioquant, Heidelberg University, Im Neuenheimer Feld 267, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany, 2Biochemie Zentrum Heidelberg (BZH), Heidelberg University, Im Neuenheimer Feld 328, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany, 3Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Tohoku University, Sendai, Miyagi 980-8578, Japan and 4Department of Pharmacology and Moores Cancer Center, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA Received February 10, 2019; Revised April 13, 2019; Editorial Decision April 24, 2019; Accepted May 01, 2019 ABSTRACT great use in tinkering with signalling pathways in living sys- tems (5). G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) control multi- Ligand binding to GPCRs induces conformational ple physiological states by transducing a multitude changes that lead to binding and activation of G-proteins of extracellular stimuli into the cell via coupling to situated on the inner cell membrane. Most of mammalian intra-cellular heterotrimeric G-proteins. Deciphering GPCRs couple with more than one G-protein giving each which G-proteins couple to each of the hundreds receptor a distinct coupling profile (6) and thus specific of GPCRs present in a typical eukaryotic organism downstream cellular responses. Determining these coupling is therefore critical to understand signalling. Here, profiles is critical to understand GPCR biology and phar- we present PRECOG (precog.russelllab.org): a web- macology. Despite decades of research and hundreds of ob- server for predicting GPCR coupling, which allows served interactions, coupling information is still missing for users to: (i) predict coupling probabilities for GPCRs many receptors and sequence determinants of coupling- specificity are still largely unknown. -

SUMF1 Enhances Sulfatase Activities in Vivo in Five Sulfatase Deficiencies

SUMF1 enhances sulfatase activities in vivo in five sulfatase deficiencies Alessandro Fraldi, Alessandra Biffi, Alessia Lombardi, Ilaria Visigalli, Stefano Pepe, Carmine Settembre, Edoardo Nusco, Alberto Auricchio, Luigi Naldini, Andrea Ballabio, et al. To cite this version: Alessandro Fraldi, Alessandra Biffi, Alessia Lombardi, Ilaria Visigalli, Stefano Pepe, et al.. SUMF1 enhances sulfatase activities in vivo in five sulfatase deficiencies. Biochemical Journal, Portland Press, 2007, 403 (2), pp.305-312. 10.1042/BJ20061783. hal-00478708 HAL Id: hal-00478708 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00478708 Submitted on 30 Apr 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Biochemical Journal Immediate Publication. Published on 8 Jan 2007 as manuscript BJ20061783 SUMF1 enhances sulfatase activities in vivo in five sulfatase deficiencies Alessandro Fraldi*1, Alessandra Biffi*2,3¥, Alessia Lombardi1, Ilaria Visigalli2, Stefano Pepe1, Carmine Settembre1, Edoardo Nusco1, Alberto Auricchio1, Luigi Naldini2,3, Andrea Ballabio1,4 and Maria Pia Cosma1¥ * These authors contribute equally to this work 1TIGEM, via P Castellino, 111, 80131 Naples, Italy 2San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy (HSR-TIGET), H. San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan 20132, Italy 3Vita Salute San Raffaele University Medical School, H. -

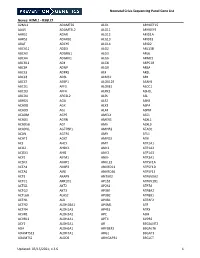

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, C12Q 1/68 (2018.01) A61P 31/18 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, C12Q 1/70 (2006.01) HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (21) International Application Number: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, PCT/US2018/056167 OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (22) International Filing Date: SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 16 October 2018 (16. 10.2018) TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (26) Publication Language: English GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 62/573,025 16 October 2017 (16. 10.2017) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, ΓΕ , IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, (71) Applicant: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, TECHNOLOGY [US/US]; 77 Massachusetts Avenue, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (US). -

Variation in Protein Coding Genes Identifies Information

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/679456; this version posted June 21, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Animal complexity and information flow 1 1 2 3 4 5 Variation in protein coding genes identifies information flow as a contributor to 6 animal complexity 7 8 Jack Dean, Daniela Lopes Cardoso and Colin Sharpe* 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Institute of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 25 School of Biological Science 26 University of Portsmouth, 27 Portsmouth, UK 28 PO16 7YH 29 30 * Author for correspondence 31 [email protected] 32 33 Orcid numbers: 34 DLC: 0000-0003-2683-1745 35 CS: 0000-0002-5022-0840 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 Abstract bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/679456; this version posted June 21, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Animal complexity and information flow 2 1 Across the metazoans there is a trend towards greater organismal complexity. How 2 complexity is generated, however, is uncertain. Since C.elegans and humans have 3 approximately the same number of genes, the explanation will depend on how genes are 4 used, rather than their absolute number. -

Cloning of an Alpha-TFEB Fusion in Renal Tumors Harboring the T(6;11)(P21;Q13) Chromosome Translocation

Cloning of an Alpha-TFEB fusion in renal tumors harboring the t(6;11)(p21;q13) chromosome translocation Ian J. Davis*†, Bae-Li Hsi‡, Jason D. Arroyo*, Sara O. Vargas§, Y. Albert Yeh§, Gabriela Motyckova*, Patricia Valencia*, Antonio R. Perez-Atayde§, Pedram Argani¶, Marc Ladanyiʈ, Jonathan A. Fletcher*‡, and David E. Fisher*†** *Department of Pediatric Oncology, Dana–Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA 02115; Departments of †Medicine and §Pathology, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA 02115; ‡Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115; ʈDepartment of Pathology, Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10021; and ¶Department of Pathology, The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD 21287 Communicated by Phillip A. Sharp, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, March 12, 2003 (received for review January 28, 2003) MITF, TFE3, TFEB, and TFEC comprise a transcription factor family Among members of the MiT family, TFE3 has previously been (MiT) that regulates key developmental pathways in several cell implicated in cancer-associated translocations. TFE3 transloca- lineages. Like MYC, MiT members are basic helix-loop-helix-leucine tions occur in distinctive renal carcinomas of childhood and zipper transcription factors. MiT members share virtually perfect young adults and in alveolar soft part sarcoma. In these trans- homology in their DNA binding domains and bind a common DNA locations, the DNA binding domain of TFE3 is fused to various motif. Translocations of TFE3 occur in specific subsets of human N-terminal partners, including PRCC, NonO (p54nrb), PSF, or renal cell carcinomas and in alveolar soft part sarcomas. Although ASPL (15–20). Although the mechanism through which these multiple translocation partners are fused to TFE3, each transloca- fusions contribute to oncogenesis remains unclear, several stud- tion product retains TFE3’s basic helix–loop–helix leucine zipper.