Artistic Data Visualization: Beyond Visual Analytics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue Description

INF 454: Data Visualization and User Interface Design Spring 2016 Syllabus Day/Times: TBD (4 Units) Location: TBD Instructor: Dr. Luciano Nocera Email: [email protected] Phone: (213) 740-9819 Office: PHE 412 Course TA: TBD Email: TBD Office Hours: TBD IT Support: TBD Email: TBD Office Hours: TBD Instructor’s Office Hours: TBD; other hours by appointment only. Students are advised to make appointments ahead of time in any event and be specific with the subject matter to be discussed. Students should also be prepared for their appointment by bringing all applicable materials and information. Catalogue Description One of the cornerstones of analytics is presenting the data to customers in a usable fashion. When considering the design of systems that will perform data analytic functions, both the interface for the user and the graphical depictions of data are of utmost importance, as it allows for more efficient and effective processing, leading to faster and more accurate results. To foster the best tools possible, it is important for designers to understand the principles of user interfaces and data visualization as the tools they build are used by many people - with technical and non-technical background - to perform their work. In this course, students will apply the fundamentals and techniques in a semester-long group project where they design, build and test a responsive application that runs on mobile devices and desktops and that includes graphical depictions of data for communication, analysis, and decision support. Short description: Foundational course focusing on the design, creation, understanding, application, and evaluation of data visualization and user interface design for communicating, interacting and exploring data. -

Rosenblum: Photographers at Work: a Sociology of Photographic Styles

Studies in Visual Communication Volume 6 Issue 1 Spring 1980 Article 13 1980 Rosenblum: Photographers at Work: A Sociology of Photographic Styles Dan Schiller Centre for Mass Communication Research, University of Leicester; Temple University Recommended Citation Schiller, D. (1980). Rosenblum: Photographers at Work: A Sociology of Photographic Styles. 6 (1), 87-90. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol6/iss1/13 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol6/iss1/13 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rosenblum: Photographers at Work: A Sociology of Photographic Styles This reviews and discussion is available in Studies in Visual Communication: https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol6/ iss1/13 Reviews and Discussion 87 derlying assumptions of the system or the powerful analytic capacity that it has. Nahumck is successful in this book to the extent Barbara Rosenblum. Photographers at Work: A that she introduces Laban's concepts and gives the Sociology of Photographic Styles. New York and reader some idea of the scope and conceptual power London: Holmes and Meier Publishers, 1978, 144 pp. of his system. She clearly documents her belief, which I share, in the primacy of Laban's system as the most $19.50. precise one available for analyzing movement in its Reviewed by Dan Schiller own terms. The book is particularly useful for readers Centre for Mass Communication Research, University of interested in a purely structural application of the nota tion system independent of the kinesthetic context, Leicester; Temple University. such as the comparative analysis of the steps of two related dance forms. -

Volume Rendering

Volume Rendering 1.1. Introduction Rapid advances in hardware have been transforming revolutionary approaches in computer graphics into reality. One typical example is the raster graphics that took place in the seventies, when hardware innovations enabled the transition from vector graphics to raster graphics. Another example which has a similar potential is currently shaping up in the field of volume graphics. This trend is rooted in the extensive research and development effort in scientific visualization in general and in volume visualization in particular. Visualization is the usage of computer-supported, interactive, visual representations of data to amplify cognition. Scientific visualization is the visualization of physically based data. Volume visualization is a method of extracting meaningful information from volumetric datasets through the use of interactive graphics and imaging, and is concerned with the representation, manipulation, and rendering of volumetric datasets. Its objective is to provide mechanisms for peering inside volumetric datasets and to enhance the visual understanding. Traditional 3D graphics is based on surface representation. Most common form is polygon-based surfaces for which affordable special-purpose rendering hardware have been developed in the recent years. Volume graphics has the potential to greatly advance the field of 3D graphics by offering a comprehensive alternative to conventional surface representation methods. The object of this thesis is to examine the existing methods for volume visualization and to find a way of efficiently rendering scientific data with commercially available hardware, like PC’s, without requiring dedicated systems. 1.2. Volume Rendering Our display screens are composed of a two-dimensional array of pixels each representing a unit area. -

Introduction to Geospatial Data Visualization

Introduction to Geospatial Data Visualization Lecturers: Viktor Lagutov, Katalin Szende, Joszef Laszlovsky. Ruben Mnatsakanian Duration: Fall term (September – December) Credits: 2 Course level: PhD / MA Maximum number of students: 15 Pre-requisites: none Software: GoogleEarthPro, qGIS, online mapping tools (e.g. GoogleMaps, ArcGISonline) Rapidly growing cross-disciplinary recognition and availability made Geospatial Methods in general, and Mapping, in particular, a popular approach in many research areas. Till recently, maps development had been a prerogative of cartographers and, later, experts in specialized mapping packages. Latest advances in hardware and software have opened this area to researchers in other disciplines and allowed them to enhance traditional research methods. The wide spectrum of such technologies and approaches is often referred as Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and includes, among others, mapping packages, geospatial analysis, crowdsourcing with mobile technologies, drones, online interactive data publishing. The geospatial literacy is becoming not an optional advantage for researchers and policy officers, but a basic requirement for many employers. The aim of the course is to develop basic understanding of spatially referenced data use and to explore potential applications of GIS in various research areas. The sessions provide both theoretical understanding and practical use of geospatial data and technologies for mapping societal and environmental phenomena. Students will learn basic features of GIS packages and the ways to utilize them for own research. The course is focused on practical skills in geospatial data visualization (mapping) and consists of • Theoretical sessions on principles of geospatial data visualization, cartography and GIS basics; • Practicals on learning GIS methods and getting mapping skills using free open source packages; • Supervised and independent students’ work on individual course projects. -

Visual Literacy of Infographic Review in Dkv Students’ Works in Bina Nusantara University

VISUAL LITERACY OF INFOGRAPHIC REVIEW IN DKV STUDENTS’ WORKS IN BINA NUSANTARA UNIVERSITY Suprayitno School of Design New Media Department, Bina Nusantara University Jl. K. H. Syahdan, No. 9, Palmerah, Jakarta 11480, Indonesia [email protected] ABSTRACT This research aimed to provide theoretical benefits for students, practitioners of infographics as the enrichment, especially for Desain Komunikasi Visual (DKV - Visual Communication Design) courses and solve the occurring visual problems. Theories related to infographic problems were used to analyze the examples of the student's infographic work. Moreover, the qualitative method was used for data collection in the form of literature study, observation, and documentation. The results of this research show that in general the students are less precise in the selection and usage of visual literacy elements, and the hierarchy is not good. Thus, it reduces the clarity and effectiveness of the infographic function. This is the urgency of this study about how to formulate a pattern or formula in making a work that is not only good and beautiful but also is smart, creative, and informative. Keywords: visual literacy, infographic elements, Visual Communication Design, DKV INTRODUCTION Desain Komunikasi Visual (DKV - Visual Communication Design) is a term portrayal of the process of media in communicating an idea or delivery of information that can be read or seen. DKV is related to the use of signs, images, symbols, typography, illustrations, and color. Those are all related to the sense of sight. In here, the process of communication can be through the exploration of ideas with the addition of images in the form of photos, diagrams, illustrations, and colors. -

Tree-Map: a Visualization Tool for Large Data

TREE-MAP: A VISUALIZATION TOOL FOR LARGE DATA Mahipal Jadeja Kesha Shah DA-IICT DA-IICT Gandhinagar,Gujarat Gandhinagar,Gujarat India India Tel:+91-9173535506 Tel:+91-7405217629 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION Traditional approach to represent hierarchical data is to use Tree-Maps are used to present hierarchical information on directed tree. But it is impractical to display large (in terms 2-D[1] (or 3-D [2]) displays. Tree-maps offer many features: of size as well complexity) trees in limited amount of space. based upon attribute values users can specify various cate- In order to render large trees consisting of millions of nodes gories, users can visualize as well as manipulate categorized efficiently, the Tree-Map algorithm was developed. Even file information and saving of more than one hierarchy is also system of UNIX can be represented using Tree-Map. Defi- supported [3]. nition of Tree-Maps is recursive: allocate one box for par- Various tiling algorithms are known for tree-maps namely: ent node and children of node are drawn as boxes within Binary tree, mixed treemaps, ordered, slice and dice, squar- it. Practically, it is possible to render any tree within prede- ified and strip. Transition from traditional representation fined space using this technique. It has applications in many methods to Tree-Maps are shown below. In figure 1 given fields including bio-informatics, visualization of stock port- hierarchical data and equivalent tree representation of given folio etc. This paper supports Tree-Map method for data data are shown. One can consider nodes as sets, children integration aspect of knowledge graph. -

The Importance of Vision Linda Lawrence MD, Richard D House

The Importance of Vision Linda Lawrence MD, Richard D House, BFA, BA, Lauren E Vaughan, BFA, Namita Jacob PhD December 2017 Introduction Why is the vision so important? What special role does it play in learning and guiding development from the moment of birth? What is the value of good visual functioning? How does vision affect and impact the development and activities of daily living of children and adolescents? The peripheral organs responsible for vision in humans are the eyes. Through a complex pathway that begins with focusing of the image by the eye, reception and transformation of light rays into neurological information is transmitted to the brain where we “see”. The information is then stored in the occipital lobe (the brain’s visual processing center) and is in turn transferred to other regions of the brain, where interpretation and use for motor (movement), cognition (thinking), learning and social interactions take place. Taste via the tongue’s gustatory pathways, smell through the nose’s olfactory pathways, hearing from the ears’ auditory pathways, and touch from the skin’s somatosensory pathways are the other peripheral senses that gather information from the environment and ultimately may rely on vision for interpretation. All this information is transported via complex biochemical and electrochemical pathways through the body, and integrated it into a meaningful context in the brain that is eventually acted upon by the person. Vision, as experienced through the visual system and visual perception, allows us to observe and extract information from the outside environment. Vision provides information that is not available through the other senses, and works in conjunction with different systems to help orient us in the environment, in time and space and at different ages and stages. -

Connected 2D and 3D Visualizations for the Interactive Exploration of Spatial Information

CONNECTED 2D AND 3D VISUALIZATIONS FOR THE INTERACTIVE EXPLORATION OF SPATIAL INFORMATION S. Bleisch *, S. Nebiker FHNW, University of Applied Sciences Northwestern Switzerland, Institute of Geomatics Engineering, CH-4132 Muttenz, Switzerland - (susanne.bleisch, stephan.nebiker)@fhnw.ch KEY WORDS: Geovisualization, Three-dimensional representation, Interactive, Spatial Data Exploration, Virtual globe, Development ABSTRACT: This paper describes the concepts and the successful prototypal implementation of interactively connected 2D information visualizations and data displays in 3D virtual environments for the interactive exploration of spatial data and information. Virtual globes or earth viewers such as Google Earth have become very popular over the last few years. They are used for looking at holiday destinations but more importantly also for scientific visualizations. From a geovisualization point of view we might regard 3D data or information displays as yet another representation type that adds to the multitude of information visualization methods. Combining 3D views of data sets with traditional 2D displays offers the advantage of being able to use 3D if and when this type of representation is considered useful or effective for finding new insights into a data set. The traditional and newer displays of mainly 2D information visualization may be enhanced and new insights into the data may be generated by displays of the data in a 3D virtual environment. On the other hand, data in 3D displays might be better understood by simultaneously reading and querying connected 2D representations.The paper presents a prototypal implementation of the interactively connected visualizations of spatial information in 2D views and 3D virtual environments using the brushing technique. -

From Surface Rendering to Volume

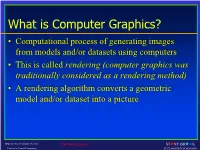

What is Computer Graphics? • Computational process of generating images from models and/or datasets using computers • This is called rendering (computer graphics was traditionally considered as a rendering method) • A rendering algorithm converts a geometric model and/or dataset into a picture Department of Computer Science CSE564 Lectures STNY BRK Center for Visual Computing STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK What is Computer Graphics? This process is also called scan conversion or rasterization How does Visualization fit in here? Department of Computer Science CSE564 Lectures STNY BRK Center for Visual Computing STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Computer Graphics • Computer graphics consists of : 1. Modeling (representations) 2. Rendering (display) 3. Interaction (user interfaces) 4. Animation (combination of 1-3) • Usually “computer graphics” refers to rendering Department of Computer Science CSE564 Lectures STNY BRK Center for Visual Computing STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Computer Graphics Components Department of Computer Science CSE364 Lectures STNY BRK Center for Visual Computing STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Surface Rendering • Surface representations are good and sufficient for objects that have homogeneous material distributions and/or are not translucent or transparent • Such representations are good only when object boundaries are important (in fact, only boundary geometric information is available) • Examples: furniture, mechanical objects, plant life • Applications: video games, virtual reality, computer- aided design Department of -

Chapter 6: Visual Communication

Chapter 6: Visual Communication This chapter will introduce you to some basic concepts in communicating with an audience through computer graphics. It will discuss the use of shapes, color, lighting, viewing, labels and legends, and motion, present issues in creating meaningful interaction and taking cultural differences into account in communication, and describe several techniques for presenting higher-dimensional information to the user. These discussions use a number of examples, and the chapter shows you how to implement many of these in OpenGL. This is something of an eclectic collection of information but it will give you valuable background on communication that can help you create more effective computer graphics programs. When you have completed this chapter, you should be able to see the difference between effective and ineffective graphics presentations and be able to identify many of the graphical techniques that make a graphic presentation effective. You should also be able to implement these techniques in your own graphics programming. In order to benefit from this chapter, you need an understanding of the basic concepts of communication, of visual vocabularies for different kinds of users, and of shaping information with the knowledge of the audience and with certain goals. You also need enough computer graphics skills to understand how these communications are created and to create them yourself. Introduction Computer graphics has achieved remarkable things in communicating information to specialists, to informed communities, and to the public at large. This is different from the entertainment areas where computer graphics gets a lot of press because it has the goal of helping the user of the interactive system or the viewer of a well-developed presentation to have a deeper understanding of a complex topic. -

Infovis and Statistical Graphics: Different Goals, Different Looks1

Infovis and Statistical Graphics: Different Goals, Different Looks1 Andrew Gelman2 and Antony Unwin3 20 Jan 2012 Abstract. The importance of graphical displays in statistical practice has been recognized sporadically in the statistical literature over the past century, with wider awareness following Tukey’s Exploratory Data Analysis (1977) and Tufte’s books in the succeeding decades. But statistical graphics still occupies an awkward in-between position: Within statistics, exploratory and graphical methods represent a minor subfield and are not well- integrated with larger themes of modeling and inference. Outside of statistics, infographics (also called information visualization or Infovis) is huge, but their purveyors and enthusiasts appear largely to be uninterested in statistical principles. We present here a set of goals for graphical displays discussed primarily from the statistical point of view and discuss some inherent contradictions in these goals that may be impeding communication between the fields of statistics and Infovis. One of our constructive suggestions, to Infovis practitioners and statisticians alike, is to try not to cram into a single graph what can be better displayed in two or more. We recognize that we offer only one perspective and intend this article to be a starting point for a wide-ranging discussion among graphics designers, statisticians, and users of statistical methods. The purpose of this article is not to criticize but to explore the different goals that lead researchers in different fields to value different aspects of data visualization. Recent decades have seen huge progress in statistical modeling and computing, with statisticians in friendly competition with researchers in applied fields such as psychometrics, econometrics, and more recently machine learning and “data science.” But the field of statistical graphics has suffered relative neglect. -

Designing for Social Data Analysis

IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VISUALIZATION AND COMPUTER GRAPHICS, VOL. 12, NO. 4, JULY/AUGUST 2006 549 Designing for Social Data Analysis Martin Wattenberg and Jesse Kriss Abstract—The NameVoyager, a Web-based visualization of historical trends in baby naming, has proven remarkably popular. We describe design decisions behind the application and lessons learned in creating an application that makes do-it-yourself data mining popular. The prime lesson, it is hypothesized, is that an information visualization tool may be fruitfully viewed not as a tool but as part of an online social environment. In other words, to design a successful exploratory data analysis tool, one good strategy is to create a system that enables “social” data analysis. We end by discussing the design of an extension of the NameVoyager to a more complex data set, in which the principles of social data analysis played a guiding role. Index Terms—Design study, time-varying data visualization, human-computer interaction, social data analysis. æ 1INTRODUCTION N February of 2005, Laura Wattenberg, the wife of the first self-reports also lead to an observation about the Name- Iauthor, published a guide to American baby names called Voyager: Usage patterns are strongly social and seem more The Baby Name Wizard [16]. To help call attention to the closely related to those of online multiplayer games than to book, a Web-based visualization applet, the NameVoyager a conventional single-user statistical tool. Indeed, users [10], was launched. The NameVoyager lets users interac- seem to fall neatly into Richard Bartle’s well-known tively explore name data—specifically, historical name popularity figures.