The Drift of Ice Island WH-5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dukes County Intelligencer

Journal of History of Martha’s Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands THE DUKES COUNTY INTELLIGENCER VOL. 55, NO. 1 WINTER 2013 Left Behind: George Cleveland, George Fred Tilton & the Last Whaler to Hudson Bay Lagoon Heights Remembrances The Big One: Hurricane of ’38 Membership Dues Student ..........................................$25 Individual .....................................$55 (Does not include spouse) Family............................................$75 Sustaining ...................................$125 Patron ..........................................$250 Benefactor...................................$500 President’s Circle ......................$1000 Memberships are tax deductible. For more information on membership levels and benefits, please visit www.mvmuseum.org To Our Readers his issue of the Dukes County Intelligencer is remarkable in its diver- Tsity. Our lead story comes from frequent contributor Chris Baer, who writes a swashbuckling narrative of two of the Vineyard’s most adventur- ous, daring — and quirky — characters, George Cleveland and George Fred Tilton, whose arctic legacies continue to this day. Our second story came about when Florence Obermann Cross suggested to a gathering of old friends that they write down their childhood memories of shared summers on the Lagoon. The result is a collective recollection of cottages without electricity or water; good neighbors; artistic and intellectual inspiration; sailing, swimming and long-gone open views. This is a slice of Oak Bluffs history beyond the more well-known Cottage City and Campground stories. Finally, the Museum’s chief curator, Bonnie Stacy, has reminded us that 75 years ago the ’38 hurricane, the mother of them all, was unannounced and deadly, even here on Martha’s Vineyard. — Susan Wilson, editor THE DUKES COUNTY INTELLIGENCER VOL. 55, NO. 1 © 2013 WINTER 2013 Left Behind: George Cleveland, George Fred Tilton and the Last Whaler to Hudson Bay by Chris Baer ...................................................................................... -

Visitor Guide Photo Pat Morrow

Visitor Guide Photo Pat Morrow Bear’s Gut Contact Us Nain Office Nunavik Office Telephone: 709-922-1290 (English) Telephone: 819-337-5491 Torngat Mountains National Park has 709-458-2417 (French) (English and Inuttitut) two offices: the main Administration Toll Free: 1-888-922-1290 Toll Free: 1-888-922-1290 (English) office is in Nain, Labrador (open all E-Mail: [email protected] 709-458-2417 (French) year), and a satellite office is located in Fax: 709-922-1294 E-Mail: [email protected] Kangiqsualujjuaq in Nunavik (open from Fax: 819-337-5408 May to the end of October). Business hours Mailing address: Mailing address: are Monday-Friday 8 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. Torngat Mountains National Park Torngat Mountains National Park, Box 471, Nain, NL Box 179 Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik, QC A0P 1L0 J0M 1N0 Street address: Street address: Illusuak Cultural Centre Building 567, Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik, QC 16 Ikajutauvik Road, Nain, NL In Case Of Emergency In case of an emergency in the park, Be prepared to tell the dispatcher: assistance will be provided through the • The name of the park following 24 hour emergency numbers at • Your name Jasper Dispatch: • Your sat phone number 1-877-852-3100 or 1-780-852-3100. • The nature of the incident • Your location - name and Lat/Long or UTM NOTE: The 1-877 number may not work • The current weather – wind, precipitation, with some satellite phones so use cloud cover, temperature, and visibility 1-780-852-3100. 1 Welcome to TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Torngat Mountains National Park 1 Welcome 2 An Inuit Homeland The spectacular landscape of Torngat Mountains Planning Your Trip 4 Your Gateway to Torngat National Park protects 9,700 km2 of the Northern Mountains National Park 5 Torngat Mountains Base Labrador Mountains natural region. -

Forest Sustainability in the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada

Forest sustainability in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada Client: Engie - Electrabel boulevard Simon Bolívar B-1000 Bruxelles Project No.: 130373 Juin 2018 SGS Belgium SA/NV Parc Créalys – Rue Phocas Lejeune, 4 – B5032 Gembloux (Belgium) Tel. +32 (0)81/ 715.160 – e-mail : [email protected] www.sgs.com Member of SGS Group (Société Générale de Surveillance) Engie – Electrabel Forest sustainability in Newfoundland and Labrador CONTENTS 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 4 2 Newfoundland and Labrador forests overview ................................................................................ 4 2.1 Location and distribution .......................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Ecological zones ...................................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Forest ownership ................................................................................................................... 14 2.4 Competent authorities ........................................................................................................... 15 2.5 Overview of wood-related industry ........................................................................................ 18 3 Sustainability of Newfoundland and Labrador forest ..................................................................... 20 3.1 Evolution -

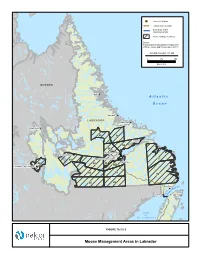

Moose Management Areas in Labrador !

"S Converter Station Transmission Corridor Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor Moose Management Area Source: Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation (2011) FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_550 0 75 150 Kilometres QUEBEC Nain ! A t l a n t i c O c e a n Hopedale ! LABRADOR Makkovik ! Postville ! Schefferville! 85 56 Rigolet ! 55 54 North West River ! ! Churchill Falls Sheshatshiu ! Happy Valley-Goose Bay 57 51 ! ! Mud Lake 48 52 53 53A Labrador City / Wabush ! "S 60 59 58 50 49 Red Bay Isle ! elle f B o it a tr Forteau ! S St. Anthony ! G u l f o f St. Lawrence ! Sept-Îles! Portland Creek! Cat Arm FIGURE 10.3.5-2 Twillingate! ! Moose Management Areas in Labrador ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Port Hope Simpson ! Mary's Harbour ! LABRADOR "S Converter Station Red Bay QUEBEC ! Transmission Corridor ± Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor Forteau ! 1 ! Large Game Management Areas St. Anthony 45 National Park 40 Source: Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation (2011) 39 FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_551 0 50 100 Kilometres 2 A t l a n t i c 3 O c e a n 14 4 G u l f 41 23 Deer Lake 15 22 o f ! 5 41 ! Gander St. Lawrence ! Grand Falls-Windsor ! 13 42 Corner Brook 7 24 16 21 6 12 27 29 43 17 Clarenville ! 47 28 8 20 11 18 25 29 26 34 9 ! St. John's 19 37 35 10 44 "S 30 Soldiers Pond 31 33 Channel-Port aux Basques ! ! Marystown 32 36 38 FIGURE 10.3.5-3 Moose and Black Bear Management Areas in Newfoundland Labrador‐Island Transmission Link Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 10 Existing Biophysical Environment Moose densities on the Island of Newfoundland are considerably higher than in Labrador, with densities ranging from a low of 0.11 moose/km2 in MMA 19 (1997 survey) to 6.82 moose/km2 in MMA 43 (1999) (Stantec 2010d). -

Ice Navigation in Canadian Waters

Ice Navigation in Canadian Waters Published by: Icebreaking Program, Maritime Services Canadian Coast Guard Fisheries and Oceans Canada Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0E6 Cat. No. Fs154-31/2012E-PDF ISBN 978-1-100-20610-3 Revised August 2012 ©Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada 2012 Important Notice – For Copyright and Permission to Reproduce, please refer to: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/notices-avis-eng.htm Note : Cette publication est aussi disponible en français. Cover photo: CCGS Henry Larsen in Petermann Fjord, Greenland, by ice island in August 2012. Canadian Coast Guard Ice Navigation in Canadian Waters Record of Amendments RECORD OF AMENDMENTS TO ICE NAVIGATION IN CANADIAN WATERS (2012 VERSION) FROM MONTHLY NOTICES TO MARINERS NOTICES TO INSERTED DATE SUBJECT MARINERS # BY Note: Any inquiries as to the contents of this publication or reports of errors or omissions should be directed to [email protected] Revised August 2012 Page i of 153 Canadian Coast Guard Ice Navigation in Canadian Waters Foreword FOREWORD Ice Navigation in Canadian Waters is published by the Canadian Coast Guard in collaboration with Transport Canada Marine Safety, the Canadian Ice Service of Environment Canada and the Canadian Hydrographic Service of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The publication is intended to assist ships operating in ice in all Canadian waters, including the Arctic. This document will provide Masters and watchkeeping crew of vessels transiting Canadian ice-covered waters with the necessary understanding of the regulations, shipping support services, hazards and navigation techniques in ice. Chapter 1, Icebreaking and Shipping Support Services, pertains to operational considerations, such as communications and reporting requirements as well as ice advisories and icebreaker support within Canadian waters. -

Low Arctic Tundra

ECOREGION Forest Barren Tundra Bog L1 Low Arctic Tundra NF 1 he Low Arctic This is also the driest region in Labrador; TTundra ecoregion the average annual precipitation is only 500 mm, 2 is located at the very which occurs mainly in the form of snow. Not n o r t h e r n t i p o f surprisingly, human habitation in this ecoregion Labrador. It extends south from Cape Chidley to is limited and non-permanent. 3 the Eclipse River, and is bordered by Quebec on In most years, coastal ice continues well the west and the Labrador Sea on the east. This into summer (sometimes not breaking up until region is characterized by a severe, stark beauty: August), which is longer than anywhere else on 4 vast stretches of exposed bedrock, boulders, the Labrador coast. Permafrost is continuous in and bare soil are broken only by patches of the valleys and mountains inland, and moss and lichens. There are no trees or discontinuous in coastal areas. 5 tall shrubs here and other vegetation is The large amount of exposed soil and extremely limited. bedrock, combined with the harsh climate, 6 The topography of the Low Arctic results in sparse vegetation throughout the Tundra includes flat coastal plains in the entire ecoregion. Seasonal flooding also north near Ungava Bay, and low steep- restricts the distribution of plants on valley 7 sided hills in the south with elevation up to floors. Because this area has no forests, 630 metres above sea level. In hilly it is true tundra. -

EXERCISE CARIBE WAVE 11 a Caribbean Tsunami Warning Exercise Participant Handbook 23 March 2011

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Technical Series 93 EXERCISE CARIBE WAVE 11 A Caribbean Tsunami Warning Exercise Participant Handbook 23 March 2011 UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission technical series 93 EXERCISE CARIBE WAVE 11 A Caribbean Tsunami Warning Exercise 23 March 2011 Prepared by the Intergovernmental Coordination Group for the Tsunami and other Coastal Hazards Warning System for the Caribbean Sea and Adjacent Regions UNESCO 2010 IOC Technical Series, 93 Paris, Novembre 2010 English/ French/ Spanish ∗ The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariats of UNESCO and IOC concerning the legal status of any country or territory, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of the frontiers of any country or territory. For bibliographic purposes, this document should be cited as follows: Commission océanographique intergouvernementale. Exercise Caribe Wave 11.A Caribbean Tsunami Warning Exercise, 23 March 2011. IOC Technical Series No. 93. Paris, UNESCO, 2011. (English/ French/ Spanish) (IOC/2010/TS/93) Printed in 2010 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP UNESCO 2010 Printed in France ∗ Appendices III, IV, V and VI are available in English only IOC Technical Series No. 93 page (i) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. BACKGROUND..........................................................................................................1 -

Investigating the Certifiability of Nunatsiavut's Commercial Fisheries

Investigating the Certifiability of Nunatsiavut’s Commercial Fisheries: The Case of the Marine Stewardship Council By Justin Schaible Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Marine Management at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia December, 2019 © Justin Schaible, 2019 Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................................................... III LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................................................................... IV ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................................................. V LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................................... VI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................................ VII CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. MANAGEMENT PROBLEM .................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2. RESEARCH QUESTION ...................................................................................................................................... -

Gray-Cheeked Thrush (Catharus Minimus)

The Status of Gray-cheeked Thrush (Catharus minimus) in Newfoundland and Labrador Gray-cheeked Thrush, Gull Island, Witless Bay Photo by Dave Fifield prepared for THE SPECIES STATUS ADVISORY COMMITTEE by Kate Dalley, Kristin Powell, and Darroch Whitaker Biology Department, Acadia University Wolfville Nova Scotia, B4P 2R6 Submitted 18 March, 2005 STATUS REPORT Catharus minimus (Lafresnaye 1848) [previously Hylocichla minima] Common Name: Other Common Names: Gray-cheeked Thrush French – Grive à joues grises Newfoundland –Wild Eyes, Wide Eyes Inuit– Ittipornipippiok, Viu Name of population(s) or subspecies: C. minimus minimus – Newfoundland Gray-cheeked Thrush C. minimus aliciae – Northern Gray-cheeked Thrush Family: Turdidae (Thrushes) Life Form: Bird (Aves) Note: Gray-cheeked Thrush and Bicknell’s Thrush were once considered to be conspecific (AOU 1957). Recently, they have been split into two distinct species (AOU 1998) – Bicknell’s Thrush (C. bicknelli), breeding in the Maritime provinces and New England, and Gray-cheeked Thrush, breeding in Newfoundland, the Labrador Peninsula, and west to Alaska (Ouellet 1993). Gray-cheeked Thrush is distinguishable from Bicknell’s Thrush by both morphometrics and song (Marshall 2001) and recent genetic analyses support the distinct species status of Bicknell’s Thrush (Outlaw et al. 2003, McEachen et al. 2004). Many authors (Godfrey 1986, Phillips 1991, Ouellet 1996, Pyle 1997, Lowther et al. 2001) consider Gray-cheeked Thrush breeding on insular Newfoundland and the lower north shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence as a distinct subspecies, Newfoundland Gray- cheeked Thrush (C. m. minimus (Lafresnaye)). Those occupying the remainder of the species’ range are then classified as Northern Gray-cheeked Thrush (C. -

Birds of the Bowdoin-Macmillan Arcticexpedition [Jan.Auk

12 GRoss,Birds of the Bowdoin-MacMillan ArcticExpedition [Jan.Auk BIRDS 01½ THE BOWDOIN-MACMILLAN ARCTIC EX•PEDITION 1934 BY ALFRED O. GROSS Plates 2-5 THE Bowdoin-MacMillanArctic Expeditionof 1934 was for the purpose of studyingand collectingbirds and plantson the coastof Labradorand the Button Islands. The latter lie between Gray and Hudson Bay Straits off the northernend of the Labradorpeninsula. They were discoveredby Sir ThomasButton as early as 1614 but as far as I know no biologicalsurvey had been made of them previousto the presentexpedition. Certain birds suchas Fulmars and I•ittiwakes were known to be very abundantabout the islandsbut their nestingsites were unknownin that vicinity. It had been suggestedthat they probablybred on the cliffsof the Buttonsbut what life existed on those bleak and inhospitableislands was merely conjectural. Landingon the Button Islandsis extremelydifficult because of the strong tides and currents,the impenetrableice packsas well as densefogs and treacherousstorms which prevail off Cape Chidley, the "Cape Horn" of the North. CommanderDonald B. MacMillan, famousArctic explorerand alumnus of BowdoinCollege, said he couldland a party on the islands. His staunch eighty-eight-footschooner, the "Bowdoin,"was made ready for the expedi- tion. Seven Bowdoin students volunteered their services to assist in the biologicalwork and to aid in the navigationof the vesselunder MacMillan's command. Dr. David Potter, professorof botany at Clark University,and two of his studentsjoined us with the purposeof making collectionsof plants of the Labradorcoast. With thesemajor objectivesthe "Bowdoin" sailedfrom Portland, Maine, on June 16, 1934, with a personnelof fifteen men including Captain MacMillan, a first mate, an engineer,and a cook. -

Investing in Students

STUDENTS ON ICE ARCTIC YOUTH EXPEDITION 2011 Iceland • Greenland • Labrador • Nunavik PROGRAM REPORT STUDENTS ON ICE STUDENTS ON ICE is an award-winning organization POLAR EDUCATION offering unique educational expeditions to the FOUNDATION Antarctic and the Arctic. Our mandate is to provide Natural Heritage Building students, educators and scientists from around the 1740 chemin Pink world with inspiring educational opportunities at the Gatineau, Québec J9J 3N7 ends of the Earth and, in doing so, help them foster a CANADA new understanding and respect for the planet. +1 819 827 3300 studentsonice.com TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. THANK YOU .................................................................... 2 2. STUDENT TESTIMONIALS ................................................. 3-4 3. SUMMARY OF THE EXPEDITION ..................................... 5-15 a) Educational Goals, Objectives and Format b) Expedition Itinerary c) Highlights, Challenges and Student Learning Outcomes 4. POLAR AMBASSADORS PROGRAM .................................. 16 5. MEDIA ............................................................................... 17 6. PARTNERS…….……………..………………………………... 18 Page 1 Dear Government of Nunavut – Department of Environment, The Students on Ice Arctic Youth Expedition 2011 was a tremendous success! The program and experiences shared over the two-week journey exceeded my every expectation. 74 students had life-changing experiences exploring Iceland, Greenland, Labrador, and Nunavik (Northern Québec) that will undoubtedly help to shape their perspectives and their futures. The highlights were abundant: meeting the President of Iceland, visiting glaciers, waterfalls and geysers, seeing polar bears in the wild, connecting with the natural world, learning from Inuit elders, fishing for Arctic char, Inuit throat singing and drum dancing, riding in a zodiac for the first time, making new friends, discussions with education team members and touching ice bergs were just some of the many highlights experienced by the inspiring youth on our team. -

A Catch History for Atlantic Walruses (Odobenus Rosmarus Rosmarus)

A catch history for Atlantic walruses (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus ) in the eastern Canadian Arctic D. Bruce Stewart 1,* , Jeff W. Higdon 2, Randall R. Reeves 3, and Robert E.A. Stewart 4 1 Arctic Biological Consultants, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3V 1X2, Canada * Corresponding author; Email: [email protected] 2 Higdon Wildlife Consulting, 912 Ashburn Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3G 3C9, Canada 3 Okapi Wildlife Associates, 27 Chandler Lane, Hudson, Quebec, J0P 1H0, Canada 5 501 University Crescent, Freshwater Institute, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Central and Arctic Region, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3T 2N6, Canada ABSTRACT Knowledge of changes in abundance of Atlantic walruses ( Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus ) in Canada is important for assessing their current population status. This catch history collates avail - able data and assesses their value for modelling historical populations to inform population recov - ery and management. Pre-historical (archaeological), historical (e.g., Hudson’s Bay Company journals) and modern catch records are reviewed over time by data source (whaler, land-based commercial, subsistence etc.) and biological population or management stock. Direct counts of walruses landed as well as estimates based on hunt products (e.g., hides, ivory) or descriptors (e.g., Peterhead boatloads) support a minimum landed catch of over 41,300 walruses in the eastern Canadian Arctic between 1820 and 2010, using the subsample of information examined. Little is known of Inuit catches prior to 1928, despite the importance of walruses to many Inuit groups for subsistence. Commercial hunting from the late 1500s to late 1700s extirpated the Atlantic walrus from southern Quebec and the Atlantic Provinces, but there was no commercial hunt for the species in the Canadian Arctic until ca.