Rethinking Pelvic Morphological Variation and Its Relation to Parturition Status Kelly Navickas [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lab #23 Anal Triangle

THE BONY PELVIS AND ANAL TRIANGLE (Grant's Dissector [16th Ed.] pp. 141-145) TODAY’S GOALS: 1. Identify relevant bony features/landmarks on skeletal materials or pelvic models. 2. Identify the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments. 3. Describe the organization and divisions of the perineum into two triangles: anal triangle and urogenital triangle 4. Dissect the ischiorectal (ischioanal) fossa and define its boundaries. 5. Identify the inferior rectal nerve and artery, the pudendal (Alcock’s) canal and the external anal sphincter. DISSECTION NOTES: The perineum is the diamond-shaped area between the upper thighs and below the inferior pelvic aperture and pelvic diaphragm. It is divided anatomically into 2 triangles: the anal triangle and the urogenital (UG) triangle (Dissector p. 142, Fig. 5.2). The anal triangle is bounded by the tip of the coccyx, sacrotuberous ligaments, and a line connecting the right and left ischial tuberosities. It contains the anal canal, which pierced the levator ani muscle portion of the pelvic diaphragm. The urogenital triangle is bounded by the ischiopubic rami to the inferior surface of the pubic symphysis and a line connecting the right and left ischial tuberosities. This triangular space contains the urogenital (UG) diaphragm that transmits the urethra (in male) and urethra and vagina (in female). A. Anal Triangle Turn the cadaver into the prone position. Make skin incisions as on page 144, Fig. 5.4 of the Dissector. Reflect skin and superficial fascia of the gluteal region in one flap to expose the large gluteus maximus muscle. This muscle has proximal attachments to the posteromedial surface of the ilium, posterior surfaces of the sacrum and coccyx, and the sacrotuberous ligament. -

Approach to the Anterior Pelvis (Enneking Type III Resection) Bruno Fuchs, MD Phd & Franklin H.Sim, MD Indication 1

Approach to the Anterior Pelvis (Enneking Type III Resection) Bruno Fuchs, MD PhD & Franklin H.Sim, MD Indication 1. Tumors of the pubis 2. part of internal and external hemipelvectomy 3. pelvic fractures Technique 1. Positioning: Type III resections involve the excision of a portion of the symphysis or the whole pubis from the pubic symphysis to the lateral margin of the obturator foramen. The best position for these patients is the lithotomy or supine position. The patient is widely prepared and draped in the lithotomy position with the affected leg free to allow manipulation during the procedure. This allows the hip to be flexed, adducted, and externally rotated to facilitate exposure. 2. Landmarks: One should palpate the ASIS, the symphysis with the pubic tubercles, and the ischial tuberosity. 3. Incision: The incision may be Pfannenstiel like with vertical limbs set laterally along the horizontal incision depending on whether the pubic bones on both sides are resected or not. Alternatively, if only one side is resected, a curved incision following the root of the thigh may be used. This incision begins below the inguinal ligament along the medial border of the femoral triangle and extends across the medial thigh a centimeter distal to the inguinal crease and perineum, to curve distally below the ischium several centimeters (Fig.1). 4. Full thickness flaps are raised so that the anterior inferior pubic ramus is shown in its entire length, from the pubic tubercle to the ischial spine. Laterally, the adductor muscles are visualized, cranially the pectineus muscle and the pubic tubercle with the insertion of the inguinal ligament (Fig.2). -

Iliopectineal Ligament As an Important Landmark in Ilioinguinal Approach of the Anterior Acetabulum

International Journal of Anatomy and Research, Int J Anat Res 2019, Vol 7(3.3):6976-82. ISSN 2321-4287 Original Research Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.16965/ijar.2019.274 ILIOPECTINEAL LIGAMENT AS AN IMPORTANT LANDMARK IN ILIOINGUINAL APPROACH OF THE ANTERIOR ACETABULUM: A CADAVERIC MORPHOLOGIC STUDY Ayman Ahmed Khanfour *1, Ashraf Ahmed Khanfour 2. *1 Anatomy department Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University, Egypt. 2 Chairman of Orthopaedic surgery department Damanhour National Medical Institute Egypt. ABSTRACT Background: The iliopectineal ligament is the most stout anterior part of the iliopectineal membrane. It separates “lacuna musculorum” laterally from “lacuna vasorum” medially. This ligament is an important guide in the safe anterior approach to the acetabulum. Aim of the work: To study the detailed anatomy of the iliopectineal ligament demonstrating its importance as a surgical landmark in the anterior approach to the acetabulum. Material and methods: The material of this work included eight adult formalin preserved cadavers. Dissection of the groin was done for each cadaver in supine position with exposure of the inguinal ligament. The iliopectineal ligament and the three surgical windows in the anterior approach to the acetabulum were revealed. Results: Results described the detailed morphological anatomy of the iliopectineal ligament as regard its thickness, attachments and variations in its thickness. The study also revealed important anatomical measurements in relation to the inguinal ligament. The distance between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the pubic tubercle ranged from 6.7 to 10.1 cm with a mean value of 8.31±1.3. The distance between the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the blending point of the iliopectineal ligament to the inguinal ligament ranged from 1.55 to 1.92 cm with a mean value of 1.78±0.15. -

The Sacroiliac Problem: Review of Anatomy, Mechanics, and Diagnosis

The sacroiliac problem: Review of anatomy, mechanics, and diagnosis MYRON C. BEAL, DD., FAAO East Lansing, Michigan methods have evolved along with modifications in Studies of the anatomy of the the hypotheses. Unfortunately, definitive analysis sacroiliac joint are reviewed, of the sacroiliac joint problem has yet to be including joint changes associated achieved. with aging and sex. Both descriptive Two excellent reviews of the medical literature and analytical investigations of joint on the sacroiliac joint are by Solonen i and a three- movement are presented, as well as part series by Weisl. clinical hypotheses of sacroiliac joint The present treatise will review the anatomy of motion. The diagnosis of sacroiliac the sacroiliac joint, studies of sacroiliac move- joint dysfunction is described in ment, hypotheses of sacroiliac mechanics, and the detail. diagnosis of sacroiliac dysfunction. Anatomy The formation of the sacroiliac joint begins during the tenth week of intrauterine life, and the joint is fully developed by the seventh month. The joint In recent years it has been generally recognized surfaces remain flat until sometime after puberty; that the sacroiliac joints are capable of movement. smooth surfaces in the adult are the exception. The clinical significance of sacroiliac motion, or The contour of the joint surface continues to lack of motion, is still subject to debate. The role of change with age. 2m In the third and fourth decades the sacroiliac joints in body mechanics can be illus- there is an increase in the number and size of the trated by a mechanical analogy. A 1 to 2 mm. mal- elevations and depressions, which interlock and alignment of a bearing in a machine can cause ab- limit mobility. -

The Pelvis Structure the Pelvic Region Is the Lower Part of the Trunk

The pelvis Structure The pelvic region is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs. It includes several structures: the bony pelvis (or pelvic skeleton) is the skeleton embedded in the pelvic region of the trunk, subdivided into: the pelvic girdle (i.e., the two hip bones, which are part of the appendicular skeleton), which connects the spine to the lower limbs, and the pelvic region of the spine (i.e., sacrum, and coccyx, which are part of the axial skeleton) the pelvic cavity, is defined as the whole space enclosed by the pelvic skeleton, subdivided into: the greater (or false) pelvis, above the pelvic brim , the lesser (or true) pelvis, below the pelvic brim delimited inferiorly by the pelvic floor(or pelvic diaphragm), which is composed of muscle fibers of the levator ani, the coccygeus muscle, and associated connective tissue which span the area underneath the pelvis. Pelvic floor separate the pelvic cavity above from the perineum below. The pelvic skeleton is formed posteriorly (in the area of the back), by the sacrum and the coccyx and laterally and anteriorly (forward and to the sides), by a pair of hip bones. Each hip bone consists of 3 sections, ilium, ischium, and pubis. During childhood, these sections are separate bones, joined by the triradiate hyaline cartilage. They join each other in a Y-shaped portion of cartilage in the acetabulum. By the end of puberty the three bones will have fused together, and by the age of 25 they will have ossified. The two hip bones join each other at the pubic symphysis. -

7-Pelvis Nd Sacrum.Pdf

Color Code Important PELVIS & SACRUM Doctors Notes Notes/Extra explanation EDITING FILE Objectives: Describe the bony structures of the pelvis. Describe in detail the hip bone, the sacrum, and the coccyx. Describe the boundaries of the pelvic inlet and outlet. Identify the articulations of the bony pelvis. List the major differences between the male and female pelvis. List the different types of female pelvis. Overview: • check this video to have a good picture about the lecture: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PJOT1cQHFqA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3v5AsAESg1Q&feature=youtu.be • BONY PELVIS = 2 Hip Bones (lateral) + Sacrum (Posterior) + Coccyx (Posterior). • Hip bone is composed of 3 parts = Superior part (Ilium) + Lower anterior part (Pubis) + Lower posterior part (Ischium) only on the boys slides’ BONY PELVIS Location SHAPE Structure: Pelvis can be regarded as a basin with holes in its walls. The structure of the basin is composed of: Pelvis is the region of the Bowl shaped 4 bones 4 joints trunk that lies below the abdomen. 1-sacrum A. Two hip bones: These form the lateral and 2-ilium anterior walls of the bony pelvis. 3-ischium B. Sacrum: It forms most of the posterior wall. 4-pubic C. Coccyx: It forms most of the posterior wall. 5-pubic symphysis 6-Acetabulum Function # Primary: The skeleton of the pelvis is a basin-shaped ring of bones with holes in its wall connecting the vertebral column to both femora. Its primary functions are: bear the weight of the upper body when sitting and standing; transfer that weight from the axial skeleton to the lower appendicular skeleton when standing and walking; provide attachments for and withstand the forces of the powerful muscles of locomotion and posture. -

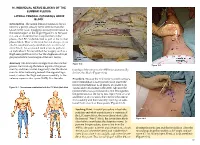

Chapter 16 – Individual Nerve Blocks of the Lumbar Plexus

16. INDIVIDUAL NERVE BLOCKS OF THE LUMBAR PLEXUS LATERAL FEMORAL CUTANEOUS NERVE BLOCK Introduction. The lateral femoral cutaneous (LFC) nerve is a purely sensory nerve derived from the L2–L3 nerve roots. It supplies sensory innervation to the lateral aspect of the thigh (Figure 16-1). Because it is one of six nerves that comprise the lumbar plexus, the LFC can be blocked as part of the lumbar plexus block. Most of the time, but not always, it can also be simultaneously anesthetized via a femoral nerve block. An occasional need arises to perform an individual LFC nerve block for surgery such as a thigh skin graft harvest or for the diagnosis of myal- gia paresthetica (a neuralgia of the LFC nerve). Anatomy. The LFC nerve emerges from the lumbar Figure 16-2 Figure 16-3 plexus, travels along the lateral aspect of the psoas muscle, and then crosses diagonally over the iliacus tionship of the nerve to the ASIS that anatomically muscle. After traversing beneath the inguinal liga- defines this block (Figure 16-2). ment, it enters the thigh and passes medially to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). It is the rela- Procedure. Because the LFC nerve is purely sensory, nerve stimulation is not typically used. Insert the needle perpendicular to all planes at a point 2 cm Figure 16-1. Dermatomes anesthetized with the LFC block (dark blue) caudal and 2 cm medial to the ASIS. Advance the needle until a loss-of-resistance is felt; this signifies the penetration of the fascia lata. Inject 5 mL of local anesthetic at this location, then redirect the needle first medially and then laterally, injecting an addi- tional 5 mL at each of these points (Figure 16-3). -

Anatomy and Physiology II

Anatomy and Physiology II Face and Head Review Name the following bones • A - Frontal bone • B - Parietal bone A • C - Sphenoid bone B • D - Temporal bone C E • E - Zygomatic bone D F • F - Maxilla G • G - Mandible Name the following bones and landmarks • Bones • A – Frontal bone B A • B – Parietal bone • C – Sphenoid bone • D – Temporal bone C • E – Occipital bone • Landmarks D • F – Mastoid process of E temporal bone F G • G – Styloid process of temporal bone Name the following landmarks • A – Temporal process of the zygomatic bone A • B – zygomatic process of the temporal bone B • These are collectively referred to as the zygomatic arch C • C – Foramen magnum Name the following landmarks and regions of the mandible • What muscle of mastication has an attachment at E? – Temporalis – Other attachment is at temporal E fossa D • What muscle of mastication has an attachment at B – Masseter – Other attachment at zygomatic arch • What are the other two C muscles of mastication? – Lateral and medial pterygoids B • Which has an attachment at A the condylar process – Lateral pterygoids Muscles of Mastication Temporalis attaching to the temporal fossa to the coranoid process of the mandible Masseter (cut) Muscles of Mastication Muscles of Mastication Muscles of Mastication Anatomy and Physiology II Pelvis Bones • The Pelvis includes the sacrum, coccyx, and the coxal bone – We will focus on the sacrum and coccyx when we look at the lumbar spine • The Hip joint includes the coxal bone and the femur • Coxal Bone – Aka Os Coxa or Innominate Bone – -

Bones of the Appendicular Skeleton

BONES OF THE APPENDICULAR SKELETON The appendicular skeleton is composed of the 126 bones of the appendages and the pectoral and pelvic girdles, which attach the limbs to the axial skeleton. Although the bones of the upper and lower limbs differ in their functions and mobility, they have the same fundamental plan – each limb is composed of three major segments connected by movable joints. LOWER LIMB Thirty-two (32) separate bones form the bony framework of each lower limb. The lower limbs carry the entire weight of the erect body and are subjected to exceptional forces when we jump or run. Thus, it is not surprising that the bones of the lower limb are thicker and stronger than the comparable bones of the upper limb. Each of the lower limb bones may be described regionally as a bone of the pelvic girdle, thigh, leg, or foot (Figure 7). Figure 7: Bones of the lower limb Pelvic (Hip) Girdle (Marieb / Hoehn – Chapter 7; Pgs. 234 – 238) The pelvic girdle is formed by the paired os coxae (coxal bones). Together with the sacrum and coccyx of the axial skeleton, this group of bones forms the bony pelvis. The ability to bear weight is more important in the pelvic girdle than the pectoral girdle. Thus, the os coxae are heavy and massive with a firm attachment to the axial skeleton. Each os coxa is a result of the fusion of three bones: the ilium, ischium, and pubis. These three bones fuse at the deep hemispherical socket, the acetabulum, which receives the femur. Figure 8: Right os coxa, lateral and medial views A. -

Digital Anatomical Measurements and Crucial Bending Areas of the Fixation

Bi et al. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders (2016) 17:125 DOI 10.1186/s12891-016-0974-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Digital anatomical measurements and crucial bending areas of the fixation route along the inferior border of the arcuate line for pelvic and acetabular fractures Chun Bi1, Xiaoxi Ji1, Fang Wang1, Dongmei Wang2 and Qiugen Wang1* Abstract Background: Better understanding of three-dimensional (3D) morphology of the pelvis at the area of inferior border of the arcuate line is very important, which could guide the surgeons to treat pelvic and acetabular fractures more efficiently. The objective of this study is to provide references for screw placement and design of anatomical internal fixators for the fixation route along the pelvic inferior border of the arcuate line. Methods: Seventy five cases of computed tomography (CT) scan data were collected using Medical Image Database in Shanghai General Hospital between December 2009 and November 2010. 44 males and 31 females, aging from 21 to 91 years (average: 57.8 years) were enrolled. Using MIMICS 13.0, these data were used for three dimensional (3D) reconstructions of pelvic model. A curve from the pubic tubercle, along the inferior border of the arcuate line, to the sacroiliac joint was depicted and then divided into 11 equal parts. The measurements of whole length of the curve, the radius of the curvature and the thickness of bone at each decile point were performed, respectively. Results: The thinnest bone thickness at acetabular area was 17.24 ± 2.90 mm and 9.94 ± 2.69 mm for male and female, respectively. -

Core Muscle Injuries

Core Muscle Injuries R. Robert Franks, D.O., FAOASM Director of Concussion Program Sports Medicine Rothman InsBtute Associate Professor Family Medicine Thomas Jefferson University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Please DO NOT Call Them Sports Hernias IntroducBon • Philadelphia athletes with core muscle injuries – Eagles’ Donovan McNabb – Eagles’ Zach Ertz – Eagles’ Kevin CurBs – Flyers’ Danny Briere IntroducBon • Incident of groin pain is 5 to 7% of all sports injuries • Most common in soccer, ice and field hockey, tennis and Australian Rules Football • Some studies have aributed increased diagnosis to more aggressive athleBc play but other studies have cited greater awareness of core muscle injuries by CerBfied AthleBc Trainers and Sports Medicine Physicians IntroducBon • One of least understood, inadequately defined and poorly researched affecBons of all sports medicine injuries • Core muscle injuries are actually several different condiBons lumped together under one common medical terminology • Can be acute, chronic, or acute on chronic variety • Found more commonly in male than female athletes DifferenBal Diagnosis • Adductor strain • OsteiBs Pubis • Iliopsoas Strains/BursiBs • Stress Fractures • Avulsion Fractures • Hip Pathology – Labral Tear, FAI, Snapping Hip • Nerve Compression Anatomy • Bony Pelvis – Ilium – Ischium – Pubis – Sacrum/Coccyx Anatomy Anatomy • So Tissue – Fibrous aachment of pubic symphysis – FibrocarBlage arBcular disc between pubic bones with aached ligaments – Most important is the arcuate ligament at the anterior, inferior -

Standardized Patient Exercise 3 IPM 1 2000

Introduction to the Practice of Medicine 1 ABDOMEN EXAM DETAILS FROM ABDOMEN VIDEO Preliminaries to the abdominal exam: S Patient should be supine for the abdomen exam. S Pull out the ledge for the patient’s legs. S Make sure the patient is appropriately draped. Let the patient lift up his/her gown to expose the abdomen. Drape the sheet across the pelvis. S Patient’s arms should be at his/her sides, NOT above his/her head. S Examiner should be on patient’s right side. This is the classic position for the abdomen exam. S Make sure the exam room door is closed. S Exam should be done on skin and not over the gown or an article of clothing. S Always inform the patient of what you are going to do before you do it. WASH HANDS 1. Identify and locate the costal margin The costal margin is made of the cartilaginous border of ribs: 7 – 10 anteriorly. 2. Identify and locate the xiphoid process The xiphoid process is a midline finger-like projection from the most inferior part of the body of the sternum. 3. Identify and locate the midline which is overlying the linea alba Linea alba runs from the xiphoid process inferiorly to the symphysis pubis. 4. Identify and locate the rectus abdominis muscle Student may ask patient to raise their head and shoulders from the supine position. These muscles run about 7-10 cm lateral to and parallel to the linea alba. The lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle is known as the linea semilunaris.