Web Pages-Optical Properties

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Zns(Ag) Zinc Sulfide Scintillation Material

ZnS(Ag) ® Zinc Sulfide Scintillation Material Properties – Density [g/cm3] ............................................... 4.09 Silver activated zinc sulfide has a very high scintillation efficiency Cleavage plane ........................... polycrystalline comparable to that of NaI(Tl). It is only available as a polycrystalline Wavelength of emission max. [nm] ........ 450 powder. Lower wavelength cutoff [nm] ................ 330 Refractive index @ emission max .......... 2.36 Photoelectron yield [% of NaI(Tl)] (for γ-rays) ZnS(Ag) has a maximum in the incident α-particles. The broad peak is ................................................................................ 130 scintillation emission spectrum at clearly above the electronic noise. Decay constant [ns] ....................................... 110 450nm. The light conversion efficiency ZnS(Ag) can be used to detect thermal is relatively poor for fast electrons neutrons if a lithium compound which may be an advantage when enriched in 6Li is incorporated. The detecting heavy ionizing particles in a alpha particle and triton from the 6Li relatively intense γ-ray background. (n, α) 3H reaction produce scintilla- Scintillation decay times between tions upon interacting with the several hundreds of ns and 10µs are ZnS(Ag). The figure also shows a reported and phosphorescence of still thermal neutron spectrum. longer duration has been noted. Another use for ZnS(Ag) is for the Thicknesses greater than about 25 detection of fast neutrons. A fast mg/cm2 become unusable because of neutron detector is made by imbed- the opacity of the multicrystalline ding the ZnS(Ag) in a clear hydrog- layer to its own luminescence. enous compound. The neutrons are Its use is limited to thin screens used detected by measuring the recoiling primarily for α-particles or other proton from a neutron proton heavy ion detection. -

Enhanced Total Internal Reflection Using Low-Index Nanolattice Materials

Letter Vol. 42, No. 20 / October 15 2017 / Optics Letters 4123 Enhanced total internal reflection using low-index nanolattice materials XU A. ZHANG,YI-AN CHEN,ABHIJEET BAGAL, AND CHIH-HAO CHANG* Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27695, USA *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received 4 August 2017; revised 14 September 2017; accepted 16 September 2017; posted 19 September 2017 (Doc. ID 303972); published 9 October 2017 Low-index materials are key components in integrated Although naturally occurring materials with low refractive photonics and can enhance index contrast and improve per- indices are limited, there are significant research efforts to formance. Such materials can be constructed from porous artificially create low-index materials close to the index of materials, which generally lack mechanical strength and air. These new materials consist of porous structures through are difficult to integrate. Here we demonstrate enhanced to- various conventional fabrication techniques, such as oblique tal internal reflection (TIR) induced by integrating robust deposition [5–9], the sol-gel process [10], and chemical vapor nanolattice materials with periodic architectures between deposition [11]. Due to the air voids, the fabricated porous high-index media. The transmission measurement from structures can have effective refractive indices lower than the the multilayer stack illustrates a cutoff at about a 60° inci- solid material components. However, such materials typically dence angle, indicating an enhanced light trapping effect lack mechanical stability and can induce optical scattering be- through TIR. Light propagation in the nanolattice material cause of the random architectures of the structures. -

PHYSICS Glossary

Glossary High School Level PHYSICS Glossary English/Haitian TRANSLATION OF PHYSICS TERMS BASED ON THE COURSEWORK FOR REGENTS EXAMINATIONS IN PHYSICS WORD-FOR-WORD GLOSSARIES ARE USED FOR INSTRUCTION AND TESTING ACCOMMODATIONS FOR ELL/LEP STUDENTS THE STATE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT / THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, ALBANY, NY 12234 NYS Language RBERN | English - Haitian PHYSICS Glossary | 2016 1 This Glossary belongs to (Student’s Name) High School / Class / Year __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ NYS Language RBERN | English - Haitian PHYSICS Glossary | 2016 2 Physics Glossary High School Level English / Haitian English Haitian A A aberration aberasyon ability kapasite absence absans absolute scale echèl absoli absolute zero zewo absoli absorption absòpsyon absorption spectrum espèk absòpsyon accelerate akselere acceleration akselerasyon acceleration of gravity akselerasyon pezantè accentuate aksantye, mete aksan sou accompany akonpaye accomplish akonpli, reyalize accordance akòdans, konkòdans account jistifye, eksplike accumulate akimile accuracy egzatitid accurate egzat, presi, fidèl achieve akonpli, reyalize acoustics akoustik action aksyon activity aktivite actual reyèl, vre addition adisyon adhesive adezif adjacent adjasan advantage avantaj NYS Language RBERN | English - Haitian PHYSICS Glossary | 2016 3 English Haitian aerodynamics ayewodinamik air pollution polisyon lè air resistance -

Introduction 1

1 1 Introduction . ex arte calcinati, et illuminato aeri [ . properly calcinated, and illuminated seu solis radiis, seu fl ammae either by sunlight or fl ames, they conceive fulgoribus expositi, lucem inde sine light from themselves without heat; . ] calore concipiunt in sese; . Licetus, 1640 (about the Bologna stone) 1.1 What Is Luminescence? The word luminescence, which comes from the Latin (lumen = light) was fi rst introduced as luminescenz by the physicist and science historian Eilhardt Wiede- mann in 1888, to describe “ all those phenomena of light which are not solely conditioned by the rise in temperature,” as opposed to incandescence. Lumines- cence is often considered as cold light whereas incandescence is hot light. Luminescence is more precisely defi ned as follows: spontaneous emission of radia- tion from an electronically excited species or from a vibrationally excited species not in thermal equilibrium with its environment. 1) The various types of lumines- cence are classifi ed according to the mode of excitation (see Table 1.1 ). Luminescent compounds can be of very different kinds: • Organic compounds : aromatic hydrocarbons (naphthalene, anthracene, phenan- threne, pyrene, perylene, porphyrins, phtalocyanins, etc.) and derivatives, dyes (fl uorescein, rhodamines, coumarins, oxazines), polyenes, diphenylpolyenes, some amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine), etc. + 3 + 3 + • Inorganic compounds : uranyl ion (UO 2 ), lanthanide ions (e.g., Eu , Tb ), doped glasses (e.g., with Nd, Mn, Ce, Sn, Cu, Ag), crystals (ZnS, CdS, ZnSe, CdSe, 3 + GaS, GaP, Al 2 O3 /Cr (ruby)), semiconductor nanocrystals (e.g., CdSe), metal clusters, carbon nanotubes and some fullerenes, etc. 1) Braslavsky , S. et al . ( 2007 ) Glossary of terms used in photochemistry , Pure Appl. -

Chapter 4 Reflected Light Optics

l CHAPTER 4 REFLECTED LIGHT OPTICS 4.1 INTRODUCTION Light is a form ofelectromagnetic radiation. which may be emitted by matter that is in a suitably "energized" (excited) state (e.g.,the tungsten filament ofa microscope lamp emits light when "energized" by the passage of an electric current). One ofthe interesting consequences ofthe developments in physics in the early part of the twentieth century was the realization that light and other forms of electromagnetic radiation can be described both as waves and as a stream ofparticles (photons). These are not conflicting theories but rather complementary ways of describing light; in different circumstances. either one may be the more appropriate. For most aspects ofmicroscope optics. the "classical" approach ofdescribing light as waves is more applicable. However, particularly (as outlined in Chapter 5) when the relationship between the reflecting process and the structure and composition ofa solid is considered. it is useful to regard light as photons. The electromagnetic radiation detected by the human eye is actually only a very small part of the complete electromagnetic spectrum, which can be re garded as a continuum from the very low energies and long wavelengths characteristic ofradio waves to the very high energies (and shortwavelengths) of gamma rays and cosmic rays. As shown in Figure 4.1, the more familiar regions ofthe infrared, visible light, ultraviolet. and X-rays fall between these extremes of energy and wavelength. Points in the electromagnetic spectrum can be specified using a variety ofenergy or wavelength units. The most com mon energy unit employed by physicists is the electron volt' (eV). -

Optical Properties of Tio2 Based Multilayer Thin Films: Application to Optical Filters

Int. J. Thin Fil. Sci. Tec. 4, No. 1, 17-21 (2015) 17 International Journal of Thin Films Science and Technology http://dx.doi.org/10.12785/ijtfst/040104 Optical Properties of TiO2 Based Multilayer Thin Films: Application to Optical Filters. M. Kitui1, M. M Mwamburi2, F. Gaitho1, C. M. Maghanga3,*. 1Department of Physics, Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, P.O. Box 190, 50100, Kakamega, Kenya. 2Department of Physics, University of Eldoret, P.O. Box 1125 Eldoret, Kenya. 3Department of computer and Mathematics, Kabarak University, P.O. Private Bag Kabarak, Kenya. Received: 6 Jul. 2014, Revised: 13 Oct. 2014, Accepted: 19 Oct. 2014. Published online: 1 Jan. 2015. Abstract: Optical filters have received much attention currently due to the increasing demand in various applications. Spectral filters block specific wavelengths or ranges of wavelengths and transmit the rest of the spectrum. This paper reports on the simulated TiO2 – SiO2 optical filters. The design utilizes a high refractive index TiO2 thin films which were fabricated using spray Pyrolysis technique and low refractive index SiO2 obtained theoretically. The refractive index and extinction coefficient of the fabricated TiO2 thin films were extracted by simulation based on the best fit. This data was then used to design a five alternating layer stack which resulted into band pass with notch filters. The number of band passes and notches increase with the increase of individual layer thickness in the stack. Keywords: Multilayer, Optical filter, TiO2 and SiO2, modeling. 1. Introduction successive boundaries of different layers of the stack. The interface formed between the alternating layers has a great influence on the performance of the multilayer devices [4]. -

Determination of Zinc Sulfide Solubility to High Temperatures

Downloaded from orbit.dtu.dk on: Sep 25, 2021 Determination of Zinc Sulfide Solubility to High Temperatures Carolina Figueroa Murcia, Diana; Fosbøl, Philip Loldrup; Thomsen, Kaj; Stenby, Erling Halfdan Published in: Journal of Solution Chemistry Link to article, DOI: 10.1007/s10953-017-0648-1 Publication date: 2017 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link back to DTU Orbit Citation (APA): Carolina Figueroa Murcia, D., Fosbøl, P. L., Thomsen, K., & Stenby, E. H. (2017). Determination of Zinc Sulfide Solubility to High Temperatures. Journal of Solution Chemistry, 46(9-10), 1805-1817. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10953-017-0648-1 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Determination of Zinc Sulfide Solubility to High Temperatures Diana Carolina Figueroa Murcia1, Philip L. Fosbøl1, Kaj Thomsen1*, Erling H. Stenby2 1Center for Energy Resources Engineering, CERE, Department of Chemical and Biochemical Engineering, Technical University of Denmark, DTU 2Department of Chemistry, Technical University of Denmark, DTU * Corresponding author: Kaj Thomsen [email protected] Abstract A new experimental set-up and methodology for the measurement of ZnS solubility in aqueous solutions at 40, 60 and 80 ˚C (atmospheric pressure) is presented. -

Negative Refractive Index in Artificial Metamaterials

1 Negative Refractive Index in Artificial Metamaterials A. N. Grigorenko Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK We discuss optical constants in artificial metamaterials showing negative magnetic permeability and electric permittivity and suggest a simple formula for the refractive index of a general optical medium. Using effective field theory, we calculate effective permeability and the refractive index of nanofabricated media composed of pairs of identical gold nano-pillars with magnetic response in the visible spectrum. PACS: 73.20.Mf, 41.20.Jb, 42.70.Qs 2 The refractive index of an optical medium, n, can be found from the relation n2 = εμ , where ε is medium’s electric permittivity and μ is magnetic permeability.1 There are two branches of the square root producing n of different signs, but only one of these branches is actually permitted by causality.2 It was conventionally assumed that this branch coincides with the principal square root n = εμ .1,3 However, in 1968 Veselago4 suggested that there are materials in which the causal refractive index may be given by another branch of the root n =− εμ . These materials, referred to as left- handed (LHM) or negative index materials, possess unique electromagnetic properties and promise novel optical devices, including a perfect lens.4-6 The interest in LHM moved from theory to practice and attracted a great deal of attention after the first experimental realization of LHM by Smith et al.7, which was based on artificial metallic structures -

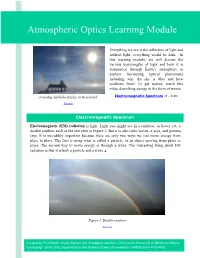

Atmospheric Optics Learning Module

Atmospheric Optics Learning Module Everything we see is the reflection of light and without light, everything would be dark. In this learning module, we will discuss the various wavelengths of light and how it is transmitted through Earth’s atmosphere to explain fascinating optical phenomena including why the sky is blue and how rainbows form! To get started, watch this video describing energy in the form of waves. A sundog and halo display in Greenland. Electromagnetic Spectrum (0 – 6:30) Source Electromagnetic Spectrum Electromagnetic (EM) radiation is light. Light you might see in a rainbow, or better yet, a double rainbow such as the one seen in Figure 1. But it is also radio waves, x-rays, and gamma rays. It is incredibly important because there are only two ways we can move energy from place to place. The first is using what is called a particle, or an object moving from place to place. The second way to move energy is through a wave. The interesting thing about EM radiation is that it is both a particle and a wave 1. Figure 1. Double rainbow Source 1 Created by Tyra Brown, Nicole Riemer, Eric Snodgrass and Anna Ortiz at the University of Illinois at Urbana- This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Champaign. 2015-2016. Supported by the National Science Foundation CAREER Grant #1254428. There are many frequencies of EM radiation that we cannot see. So if we change the frequency, we might have radio waves, which we cannot see, but they are all around us! The same goes for x-rays you might get if you break a bone. -

Optical Properties of Materials JJL Morton

Electrical and optical properties of materials JJL Morton Electrical and optical properties of materials John JL Morton Part 5: Optical properties of materials 5.1 Reflection and transmission of light 5.1.1 Normal to the interface E z=0 z E E H A H C B H Material 1 Material 2 Figure 5.1: Reflection and transmission normal to the interface We shall now examine the properties of reflected and transmitted elec- tromagnetic waves. Let's begin by considering the case of reflection and transmission where the incident wave is normal to the interface, as shown in Figure 5.1. We have been using E = E0 exp[i(kz − !t)] to describe waves, where the speed of the wave (a function of the material) is !=k. In order to express the wave in terms which are explicitly a function of the material in which it is propagating, we can write the wavenumber k as: ! !n k = = = nk0 (5.1) c c0 where n is the refractive index of the material and k0 is the wavenumber of the wave, were it to be travelling in free space. We will therefore write a wave as the following (with z replaced with whatever direction the wave is travelling in): Ex = E0 exp [i (nk0z − !t)] (5.2) In this problem there are three waves we must consider: the incident wave A, the reflected wave B and the transmitted wave C. We'll write down the equations for each of these waves, using the impedance Z = Ex=Hy, and noting the flip in the direction of H upon reflection (see Figure 5.1), and the different refractive indices and impedances for the different materials. -

Atmospheric Optics

53 Atmospheric Optics Craig F. Bohren Pennsylvania State University, Department of Meteorology, University Park, Pennsylvania, USA Phone: (814) 466-6264; Fax: (814) 865-3663; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Colors of the sky and colored displays in the sky are mostly a consequence of selective scattering by molecules or particles, absorption usually being irrelevant. Molecular scattering selective by wavelength – incident sunlight of some wavelengths being scattered more than others – but the same in any direction at all wavelengths gives rise to the blue of the sky and the red of sunsets and sunrises. Scattering by particles selective by direction – different in different directions at a given wavelength – gives rise to rainbows, coronas, iridescent clouds, the glory, sun dogs, halos, and other ice-crystal displays. The size distribution of these particles and their shapes determine what is observed, water droplets and ice crystals, for example, resulting in distinct displays. To understand the variation and color and brightness of the sky as well as the brightness of clouds requires coming to grips with multiple scattering: scatterers in an ensemble are illuminated by incident sunlight and by the scattered light from each other. The optical properties of an ensemble are not necessarily those of its individual members. Mirages are a consequence of the spatial variation of coherent scattering (refraction) by air molecules, whereas the green flash owes its existence to both coherent scattering by molecules and incoherent scattering