Art After 9/11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libeskind's Jewish Museum Berlin

Encountering empty architecture: Libeskind’s Jewish Museum Berlin Henrik Reeh Preamble In Art Is Not What You Think It Is, Claire Farago and Donald Preziosi observe how the architecture of contemporary museums inspires active relationships between exhibitions and visitors.1 Referring to the 2006 Denver Art Museum by Daniel Libeskind, they show the potentials germinating in a particular building. When artists and curators are invited to dialog with the spaces of this museum, situations of art-in-architecture may occur which go beyond the ordinary confrontation of exhibitions and spectatorship, works and visitors. Libeskind’s museum is no neutral frame in the modernist tradition of the white cube, but a heterogeneous spatiality. These considerations by Farago and Preziosi recall the encounter with earlier museums by Libeskind. Decisive experiences particularly date back to the year 1999 when his Jewish Museum Berlin was complete as a building, long before being inaugurated as an exhibition hall in 2001. Open to the public for guided tours in the meantime, the empty museum was visited by several hundred thousand people who turned a peripheral frame of future exhibitions into the center of their sensory and mental attention. Yet, the Libeskind building was less an object of contemplation than the occasion for an intense exploration of and in space. Confirming modernity’s close connection between exhibition and architecture, Libeskind’s Jewish Museum Berlin unfolds as a strangely dynamic and fragmented process, the moments of which call for elaboration and reflection. I. Architecture/exhibition Throughout modernity, exhibitions and architecture develop in a remarkably close relationship to one another. -

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project Lynne B. Sagalyn THREE YEARS after the terrorist attack of September 11,2001, plans for four key elements in rebuilding the World Trade Center (WC) site had been adopted: restoring the historic streetscape, creating a new public transportation gate- way, building an iconic skyscraper, and fashioning the 9/11 memorial. Despite this progress, however, what ultimately emerges from this heavily argued deci- sionmakmg process will depend on numerous design decisions, financial calls, and technical executions of conceptual plans-or indeed, the rebuilding plan may be redefined without regard to plans adopted through 2004. These imple- mentation decisions will determine whether new cultural attractions revitalize lower Manhattan and whether costly new transportation investments link it more directly with Long Island's commuters. These decisions will determine whether planned open spaces come about, and market forces will determine how many office towers rise on the site. In other words, a vision has been stated, but it will take at least a decade to weave its fabric. It has been a formidable challenge for a city known for its intense and frac- tious development politics to get this far. This chapter reviews the emotionally charged planning for the redevelopment of the WTC site between September 2001 and the end of 2004. Though we do not yet know how these plans will be reahzed, we can nonetheless examine how the initial plans emerged-or were extracted-from competing ambitions, contentious turf battles, intense architectural fights, and seemingly unresolvable design conflicts. World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project 25 24 Contentious City ( rebuilding the site. -

Tree of Life Selects Daniel Libeskind As Its Lead Architect

EXCERPTED FROM THE PAGES OF May 04, 2021 Tree of Life selects Daniel Libeskind as its lead architect The internationally renowned architect designed the World Trade Master Plan in New York City following 9/11. By Toby Tabachnick Daniel Libeskind, the internationally renowned architect who designed the World Trade Master Plan in New York following 9/11, has been chosen as the lead architect to reimagine the site of the Tree of Life building. Libeskind was selected unanimously by Tree of Life’s board of trustees and steering committee. The renovation of the Tree of Life building is part of the congregation’s REMEMBER. REBUILD. RENEW. campaign to commemorate the events of Oct. 27, 2018, when an antisemitic gunman murdered 11 worshippers at the three congregations housed in the building: Tree of Life, Dor Hadash and New Light. It was the most violent antisemitic attack in U.S. history. “It is with a great sense of photo by Tree of Life urgency and meaning that I “When my parents, survivors of our time and affirm the join the Tree of Life to create of the Holocaust, and I came as democratic values of our country.” a new center in Pittsburgh,” immigrants to America, we felt Libeskind’s previous projects said Libeskind in a prepared an air of freedom as Jews in this include the Jewish Museum in statement. “Our team is country,” he continued. “That Berlin and the National Holocaust committed to creating a powerful is why this project is not simply Monument in Ottawa, Canada. He and memorable space that about ‘Never Again.’ It is a project told The New York Times that he addresses the worst antisemitic that must address the persistence would be visiting the site for the first attack in United States history. -

MO Invites Visitors to Discover Animals and Robots

MO invites visitors to discover animals and robots MO is about to open its second major exhibition "Animal – Human – Robot", which hopes to foster a re-examination of the human relationship with other living beings. The purpose of the exhibition is to reveal how art features the change in the behaviour of humans towards animals and predict what kind of creatures will dominate in the future? “This is an exhibition on change. What have animals and other forms of life, including non-human creatures, become in our life, and what have we become for them? Who will survive, who will win, and who will determine the future? Relationship with other life forms and man-made artificial intelligence tells a lot about us, people, so we invite everybody to rediscover themselves and experience it at MO Museum,” says Milda Ivanauskienė, Director at MO. “So far, representation of the relationship between human and other beings in Lithuanian art has not been thoroughly analysed. Rapidly developing bio-based and information technologies have generated particular interest in various life forms. That is why it was very interesting to take a look at the MO collection from this perspective,” says art historian, one of the exhibition curators Erika Grigoravičienė, explaining the motives of the exhibition. "As our own lives are taken over by technologies, the issue of human co-existence with others seems even more interesting to us. It looks like people will have to abandon the idea of their supremacy, recognise biodiversity, and try out hybrid models of the society,” adds the second curator of the exhibition Ugnė Paberžytė. -

APC WTC Thesis V8 090724

A Real Options Case Study: The Valuation of Flexibility in the World Trade Center Redevelopment by Alberto P. Cailao B.S. Civil Engineering, 2001 Wentworth Institute of Technology Submitted to the Center for Real Estate in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2009 ©2009 Alberto P. Cailao All rights reserved. The author hereby grants MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author________________________________________________________________________ Center for Real Estate July 24, 2009 Certified by_______________________________________________________________________________ David Geltner Professor of Real Estate Finance, Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by_____________________________________________________________________________ Brian A. Ciochetti Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development A Real Options Case Study: The Valuation of Flexibility in the World Trade Center Redevelopment by Alberto P. Cailao Submitted to the Center for Real Estate on July 24, 2009 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development Abstract This thesis will apply the past research and methodologies of Real Options to Tower 2 and Tower 3 of the World Trade Center redevelopment project in New York, NY. The qualitative component of the thesis investigates the history behind the stalled development of Towers 2 and 3 and examines a potential contingency that could have mitigated the market risk. The quantitative component builds upon that story and creates a hypothetical Real Options case as a framework for applying and valuing building use flexibility in a large-scale, politically charged, real estate development project. -

September 11, Ground Zero As It Is 15 Years Later

September 11, Ground Zero as it is 15 years later - Pictures As it appears today the site affected by the 2001 terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers in New York September 11, 2016 Where for almost 30 years - from 1973 until September 11, 2001 - the Twin Towers have excelled on the southern part of Manhattan, after the two hijacked planes by militants of Al Qaeda will crashed into, for many years there has been Ground Zero, the site of destruction (a term mediated by the cold war designating an area affected by an atomic explosion). The area in the southern part of Manhattan in New York where, before the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers once stood the World Trade Center became the "Ground Zero" by definition. A political and human tragedy that, in addition to inflicting a blow to the heart of the US, has scarred the face of the city. More than hurt, she appeared as an "amputated" cities, until the Renaissance, in 2013, the One World Trade Center, also known as the Freedom Tower, the fourth tallest building in the world and symbol of the worst for almost 10 years New York terrorist massacre in American history. For the reorganization of the area and the construction of new buildings was a competition, won by the Polish-American architect Daniel Libeskind, which led to the construction of the "Tower of Freedom." At its base are located historical museum area - which extends over seven floors, mostly underground - and an outside area of the Islamist commemorating victims of the attack. -

Kevin Rampe, Interim President for the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) Opened the Meeting by Welcoming the Advisory Council Members in Attendance

LMDC ALL ADVISORY COUNCIL MEETING ON THE STUDIO DANIEL LIBESKIND’S PLAN THURSDAY, MARCH 20, 2003 5:30-8:30PM HELD AT THE OFFICES OF THE PORT AUTHORITY OF NEW YORK AND NEW JERSEY TH 111 EAST 18 STREET, NEW YORK, NY Kevin Rampe, Interim President for the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) opened the meeting by welcoming the Advisory Council members in attendance. He explained that the LMDC and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) are going to jointly retain Daniel Libeskind as the master design architect for the overall rebuilding of the World Trade Center site. Mr. Rampe introduced Alex Garvin, Vice President for Planning, Design and Development for the LMDC. Mr. Garvin went on to say that when the LMDC launched the Innovative Design Study process, New York New Visions supplied the LMDC with a list of names of architects they should contact to participate in the competition, and Daniel Libeskind was one of them. Mr. Garvin called Nina Libeskind, Daniel Libeskind’s wife, and they agreed to submit a proposal. Mr. Garvin was happy to say that Mr. Libeskind became one of the semi-finalists, and he is finally here at the end of the process with a magnificent site plan. Mr. Garvin then introduced Mr. Libeskind. Mr. Libeskind thanked all the attendees for their interest in his plan and for the chance to be involved in this spectacular process, to rebuild Ground Zero. He mentioned that the process is an exemplary democratic process because it involves citizens from all walks of life. -

Daniel Libeskind Traces of the Unborn Foreword

Second Edition CO 1995 Tlw University of :\·fichigan Cnllcp;<" of .\rchit{Yturc +Urban Plcmning & Danic!J.ibc~kinrl Editor: ;\nncttc· \\'.LeCuyer l3oo_k Desig-n : Christian LTnnTzagt I ma ge~: with the cooperation of Elizabeth G o,·a n I Stud in I .ibcskind Priming: Goetzcraft Primers, Inc·: Ann :\rhor I'rinll·d ami bound in the Lnitcd State ~ ol' :\mcrica ·}) 'J H'sc t in ~- l o n o t yp<.· U as: k nyill ~,... ~ nd Futura Book ISR'\- 0 96 14792 I 3 The Lnivcrsity or ~li c hi gan College or Architecture + Urban Pl anning 2000 Bonistccl Boukvard ,\nn Arbor. :\licltigan -Ill I 09-~069 CS.\ Daniel Libeskind traces of the unborn foreword Raoul \'Vallenberg, who graduated from the College of Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Michigan in 1935, has been called one of the century's most outstanding heroes. In 1944, as First Secretary of the Swedish legation in Budapes t, he is credited with saving more than I 00,000 Jews from death at the hands of the Nazis. The following year, Wallenberg was captured by the Russians. His fate is not known, although rumors persist that he is held in Russia even today. To honor and remember this outstanding alumnus, Sol King, a former classmate of Wallenberg's, initiated the Wallenberg lecture series in 1971. In 1976, an endowment was established to ensure that an annual lecture be offered in Raoul's honor to focus on architecture as a humane social art. Since that series began, we have been honored to have at the college a number of distinguished speakers: Nikolaus Pevsner, Rudolf Arnheim, Joseph Rykwert, Spiro Kostof, Denise Scott Brown,James Marston Fitch, Joseph Esherick, and many more. -

The Park 51/Ground Zero Controversy and Sacred Sites As Contested Space

Religions 2011, 2, 297-311; doi:10.3390/rel2030297 OPEN ACCESS religions ISSN 2077-1444 www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Article The Park 51/Ground Zero Controversy and Sacred Sites as Contested Space Jeanne Halgren Kilde University of Minnesota, 245 Nicholson Hall, 216 Pillsbury Dr. SE., Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: 612-625-6393 Received: 9 June 2011; in revised form: 14 July 2011 / Accepted: 19 July 2011 / Published: 25 July 2011 Abstract: The Park 51 controversy swept like wildfire through the media in late August of 2010, fueled by Islamophobes who oppose all advance of Islam in America. Yet the controversy also resonated with many who were clearly not caught up in the fear of Islam. This article attempts to understand the broader concern that the Park 51 project would somehow violate the Ground Zero site, and, thus, as a sign of "respect" should be moved to a different location, an argument that was invariably articulated in “spatial language” as groups debated the physical and spatial presence of the buildings in question, their relative proximity, and even the shadows they cast. This article focuses on three sets of spatial meanings that undergirded these arguments: the site as sacred ground created through trauma, rebuilding as retaliation for the attack, and the assertion of American civil religion. The article locates these meanings within a broader civic discussion of liberty and concludes that the spatialization of the controversy opened up discursive space for repressive, anti-democratic views to sway even those who believe in religious liberty, thus evidencing a deep ambivalence regarding the legitimate civic membership of Muslim Americans. -

Negotiating the Mega-Rebuilding Deal at the World Trade Center: Plans for Redevelopment

NEGOTIATING THE MEGA-REBUILDING DEAL AT THE WORLD TRADE CENTER: PLANS FOR REDEVELOPMENT DARA M. MCQUILLAN* & JOHN LIEBER ** Good morning. The current state of Lower Manhattan is the result of multiple years of planning and refinement of designs. Later I will spend a couple of minutes discussing the various buildings that we are constructing. First, to give you a little sense of perspective, Larry Silverstein,1 a quintessential New York developer, first got involved at the World Trade Center and with the Port Authority, owner of the World Trade Center,2 in 1980 when he won a bid to build 7 World Trade Center.3 In 1987, Silverstein completed the seventh tower, just north of the World Trade Center site.4 As Alex mentioned, 7 World Trade Center was not the most attractive building in New York and completely cut off Greenwich Street. Greenwich Street is the main street running through Tribeca and connects one of the most dynamic and interesting neighborhoods in New York to the financial district.5 Greenwich serves as a major link to Wall Street. I used to live in SoHo. I would walk to work at the Twin Towers every morning down Greenwich Street past the Robert DeNiro Film Center, Bazzini‘s Nuts, the parks, and the lofts of movie stars, and all of a sudden I would be in front of a 656-foot brick wall of a building. There were huge wind vortexes which often swept garbage all over the place, you could never get a cab, and it was a very * Vice President of Marketing and Communications for World Trade Center Properties, LLC, and Silverstein Properties, Inc. -

Today's News - June 20, 2003 Taking Down Damaged Building No Small Task

Home Yesterday's News Contact Us Subscribe Today's News - June 20, 2003 Taking down damaged building no small task. -- Opinions continue to fly around Ground Zero design. -- Smart bricks? -- Finding greenbacks in brownfields. -- Urban developments panned and praised in Syracuse, Toronto, Washington, DC suburbs, Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Chicago. -- Big box stores have an eye on Manhattan. -- Alliance for US/UK healthcare design firms. -- What really created the "Holyrood fiasco." -- New courthouse praised and panned. -- Renaming and reshaping a museum. To subscribe to the free daily newsletter click here Last Days for a Survivor of Sept. 11: The battered and disfigured Deutsche Bank building...deemed beyond repair- New York Times On a New Path: Daniel Libeskind has backed off demands for direct design control over a new Ground Zero PATH terminal...- NY Post Opinion: Free Larry! My analysis unveiled no hidden groundswell of support for opera houses or housing projects to replace dense commercial real estate at the site.- NY Post Smart Bricks, or a Dumb Idea? ...part of the movement toward "smart buildings"- Wired magazine Squeezing Green Out of Brownfield Development- National Real Estate Investor Developer With Stealth Reputation Changes Tactics: proposed supermall DestiNY USA planned for Syracuse...- New York Times Toronto architect Raymond Moriyama lauds community development corporation to oversee the evolution of south downtown- Canada.com Urban Experiment Revisited: After 15 Years, Planners Sharpen Their Vision of Kentlands. By Benjamin Forgey - Duany Plater-zyberk & Co.; Leon Krier; Congress for the New Urbanism- Washington Post Phoenix ready to start promoting Plaza perks: $600 million expansion of the Phoenix Civic Plaza- Arizona Republic City Observed: Transit Villages: Maybe, at long last, we will start taking mass transit seriously.. -

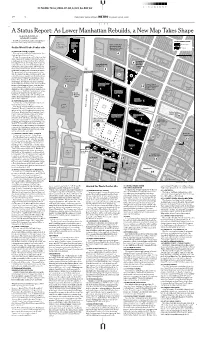

As Lower Manhattan Rebuilds, a New Map Takes Shape

ID NAME: Nxxx,2004-07-04,A,024,Bs-BW,E2 3 7 15 25 50 75 85 93 97 24 Ø N THE NEW YORK TIMES METRO SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2004 CITY A Status Report: As Lower Manhattan Rebuilds, a New Map Takes Shape By DAVID W. DUNLAP and GLENN COLLINS Below are projects in and around ground DEVELOPMENT PLAN zero and where they stood as of Friday. Embassy Goldman Suites Hotel/ Sachs Bank of New York BUILDINGS UA Battery Park Building Technology and On the World Trade Center site City theater site 125 Operations Center PARKS GREENWICH ST. 75 Park Place Barclay St. 101 Barclay St. (A) FREEDOM TOWER / TOWER 1 2 MURRAY ST. Former site of 6 World Trade Center, the 6 United States Custom House 0Feet 200 Today, the cornerstone will be laid for this WEST BROADWAY skyscraper, with about 60,000 square feet of retail space at its base, followed by 2.6 mil- Fiterman Hall, lion square feet of office space on 70 stories, 9 Borough of topped by three stories including an obser- Verizon Building Manhattan PARK PL. vation deck and restaurants. Above the en- 4 World 140 West St. Community College closed portion will be an open-air structure Financial 3 5 with wind turbines and television antennas. Center 7 World The governor’s office is a prospective ten- VESEY ST. BRIDGE Trade Center 100 Church St. ant. Occupancy is expected in late 2008. The WASHINGTON ST. 7 cost of the tower, apart from the infrastruc- 3 World 8 BARCLAY ST. ture below, is estimated at $1 billion to $1.3 Financial Center billion.