Toni Morrison: Defamiliarization and Metaphor in Song of Solomon And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHILIP ROTH and the STRUGGLE of MODERN FICTION by JACK

PHILIP ROTH AND THE STRUGGLE OF MODERN FICTION by JACK FRANCIS KNOWLES A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2020 © Jack Francis Knowles, 2020 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: Philip Roth and The Struggle of Modern Fiction in partial fulfillment of the requirements submitted by Jack Francis Knowles for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Examining Committee: Ira Nadel, Professor, English, UBC Supervisor Jeffrey Severs, Associate Professor, English, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Michael Zeitlin, Associate Professor, English, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Lisa Coulthard, Associate Professor, Film Studies, UBC University Examiner Adam Frank, Professor, English, UBC University Examiner ii ABSTRACT “Philip Roth and The Struggle of Modern Fiction” examines the work of Philip Roth in the context of postwar modernism, tracing evolutions in Roth’s shifting approach to literary form across the broad arc of his career. Scholarship on Roth has expanded in both range and complexity over recent years, propelled in large part by the critical esteem surrounding his major fiction of the 1990s. But comprehensive studies of Roth’s development rarely stray beyond certain prominent subjects, homing in on the author’s complicated meditations on Jewish identity, a perceived predilection for postmodern experimentation, and, more recently, his meditations on the powerful claims of the American nation. This study argues that a preoccupation with the efficacies of fiction—probing its epistemological purchase, questioning its autonomy, and examining the shaping force of its contexts of production and circulation— roots each of Roth’s major phases and drives various innovations in his approach. -

11 Th Grade American Literature Summer Assignment (20192020 School Y Ear)

6/26/2019 American Lit Summer Reading 2019-20 - Google Docs 11 th Grade American Literature Summer Assignment (20192020 School Y ear) Welcome to American Literature! This summer assignment is meant to keep your reading and writing skills fresh. You should choose carefully —select books that will be interesting and enjoyable for you. Any assignments that do not follow directions exactly will not be accepted. This assignment is due Friday, August 16, 2019 to your American Literature Teacher. This will count as your first formative grade and be used as a diagnostic for your writing ability. Directions: For your summer assignment, please choose o ne of the following books to read. You can choose if your book is Fiction or Nonfiction. Fiction Choices Nonfiction Choices Catch 22 by Joseph Heller The satirical story of a WWII soldier who The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace by Jeff Hobbs. An account thinks everyone is trying to kill him and hatches plot after plot to keep of a young African‑American man who escaped Newark, NJ, to attend from having to fly planes again. Yale, but still faced the dangers of the streets when he returned is, Bastard Out of Carolina by Dorothy Allison The story of an abusive “nuanced and shattering” ( People ) and “mesmeric” ( The New York Southern childhood. Times Book Review ) . The Known World by Edward P. Jones The story of a black, slave Outliers / Blink / The Tipping Point by Malcolm Gladwell Fascinating owning family. statistical studies of everyday phenomena. For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway A young American The Hot Zone: A Terrifying True Story by Richard Preston There is an anti‑fascist guerilla in the Spanish civil war falls in love with a complex outbreak of ebola virus in an American lab, and other stories of germs woman. -

SCI Newsletter XXXVI:2

2005 SCI Region V Conference An Interview with Steven Stucky Christopher Gable Ralph S. Kendrick Butler University RSK: Congratulations on winning the Indianapolis, Indiana Pulitzer Prize this year! How does one feel UPCOMING November 11–13 after winning such a distinguished award? co-hosted by Were you surprised by it, and has your life CONFERENCES Frank Felice and Michael Schelle been much different since? 2006 Region VII Conference During the second weekend of November, SS: I can’t pretend that I’m not pleased University of New Mexico 2005, approximately 48 composers from that this year my number came up. It’s not In conjunction with the John Donald all across the country converged on the that I think that objectively my piece was Robb Composers Symposium campus of Butler University for the SCI the “best” one, of course, but a committee April 2–5, 2006 Midwest Chapter (Region V) Conference. of respected peers found the piece worth Host: Christopher Shultis After nine full-length concerts in three discussing in the company of some of the E-mail: [email protected] days, we were all exhausted, but thrilled by other terrific pieces American composers the experience and warmed by the gave us over the past year. That’s enough 2006 National Conference generosity of the conference’s co-hosts, to encourage a composer to think he San Antonio, TX Frank Felice and Michael Schelle. There hasn’t been wasting his time, and to September 13-17, 2006 was networking, socializing, rehearsing, inspire him to keep trying to do his best. -

Opening the Rachel Carson Music and Campus Center

MiddlesexFall 2018 Opening the Rachel Carson Music and Campus Center MIDDLESEX FALL 2018 i From the Head of School Becoming through Bonding Last week, I heard a marvelous sentence attrib- delight, or any experience that reveals the uted to the American poet e e cummings— human spirit.” Issues can engage us, and that’s “It takes courage to grow up and become who important, the capacity to engage and want you really are”—and yes, when we articulate to contribute; and urgency can inspire us, the values of honesty, gratitude, kindness, galvanize our ability to organize, to plan, respect, and courage, that is the kind of cour- to strategize. But building relationships— age perhaps most important to the formation the real connections with others, based on of identity: the courage of integrity. At its understanding, respect, and yes, true affec- most basic, integrity requires a unity of mind, tion—is what will sustain us, motivate us, body, spirit, principles, and actions. Achieving and ultimately, over the hopefully long run that unity with consistency—building integ- of our lives, come to satisfy us. In the words rity into our lives as habit—makes us people of Carmen Beaton, our beloved, now-retired worthy of others’ trust. I would offer that any colleague, they are “the gift we give each definition of success in “finding the promise” other”—and they are the proverbial gifts that presupposes that we are worthy of trust. keep on giving, in that they join us together, Integrity is a significant challenge for all past, present, and future. -

2008 – 2009 Course Catalog

MIDDLESEX COUNTY COLLEGE CATALOG 08/09 imagine WWW.MIDDLESEXCC.EDU MIDDLESEX C O U N T Y COLLEGE 2600 Woodbridge Avenue P.O. Box 3050 Edison, New Jersey 08818-3050 732.548.6000 MIDDLESEX C O U N T Y COLLEGE Course Catalog 08 -09 MIDDLESEX COUNTY COLLEGE 2008 - 2009 Catalog MAIN CAMPus 2600 Woodbridge Avenue P.O. Box 3050 Edison, New Jersey 0888 732.548.6000 New BRUNswicK CENTER 40 New Street New Brunswick, NJ 0890 732.745.8866 PeRTH AmboY CENTER 60 Washington Street Perth Amboy, NJ 0886 732.324.0700 Foreword: The catalog is the contract between the College and the student. This catalog provides information for students, faculty, and administrators regarding the College’s policies. Requirements, course offerings, schedules, activities, tuition and fees in this catalog are subject to change without notice at any time at the sole discretion of the administration. Such changes may be of any nature, including but not limited to the elimination of programs, classes, or activities; the relocation or modification of the content of any of the foregoing; and the cancellation of a schedule of classes or other academic activities. Payment of tuition or attendance in any class shall constitute a student’s acceptance of the administration’s rights as set forth above. The Office of theR egistrar prepares the catalog. Any questions about its contents should be directed to the Registrar in Chambers Hall. Cover painting by Frank McGinley © 2007. Used by permission. The most current information can be found on the MCC website: www.middlesexcc.edu FINAL REVISED JULY , 2008, JULY 6, 2008, JULY 22, 2008, September , 2008 WWW.MIDDLESEXCC.EDU Middlesex County College MIDDLESEX COUNTY BOARD OF CHOSEN FREEHOLDERS Affirmative Action and Compliance David B. -

Pedagogical Practices Related to the Ability to Discern and Correct

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Pedagogical Practices Related to the Ability to Discern and Correct Intonation Errors: An Evaluation of Current Practices, Expectations, and a Model for Instruction Ryan Vincent Scherber Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC PEDAGOGICAL PRACTICES RELATED TO THE ABILITY TO DISCERN AND CORRECT INTONATION ERRORS: AN EVALUATION OF CURRENT PRACTICES, EXPECTATIONS, AND A MODEL FOR INSTRUCTION By RYAN VINCENT SCHERBER A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2014 Ryan V. Scherber defended this dissertation on June 18, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: William Fredrickson Professor Directing Dissertation Alexander Jimenez University Representative John Geringer Committee Member Patrick Dunnigan Committee Member Clifford Madsen Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Mary Scherber, a selfless individual to whom I owe much. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this journey would not have been possible without the care and support of my family, mentors, colleagues, and friends. Your support and encouragement have proven invaluable throughout this process and I feel privileged to have earned your kindness and assistance. To Dr. William Fredrickson, I extend my deepest and most sincere gratitude. You have been a remarkable inspiration during my time at FSU and I will be eternally thankful for the opportunity to have worked closely with you. -

Xtl /Vo0 , 6 Z Se

xtl /Vo0 , 6 Z se PERCEPTION OF TIMBRAL DIFFERENCES AMONG BASS TUBAS THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Gary Thomas Cattley, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1987 Cattley, Gary T., Perception of Timbral Differences among Bass Tubas. Master of Music (Music Education), August, 1987, 98 pp., 4 tables, 6 figures, bibliography, 74 titles. The present study explored whether musicians could (1) differentiate among the timbres of bass tubas of a single design, but constructed of different materials, (2) determine differences within certain ranges and articulations, and (3) possess different perceptual abilities depending on previous experience in low brass performance. Findings indicated that (1) tubas made to the same specifications and constructed of the same material differed as much as those of made to the same specifications, constructed of different materials; 2) significant differences in perceptibility which occurred among tubas were inconsistent across ranges and articulations, and differed due to phrase type and the specific tuba on which the phrase was played; 3) low brass players did not differ from other auditors in their perception of timbral differences. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . - . - . v LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . .*. ... .vi Chapter I. INTRODUCTION ............. Purpose of the Study Research Questions Definition Delimitations Chapter Bibliography II. REVIEW OF THE RELATED LITERATURE . 14 The Perception of Timbre Background Acoustical Attributes of Timbre Subjective Aspects of Timbre Subjective Measurement of Timbre Contextual Presentation of Stimuli The Influence of Materials on Timbre Chapter Bibliography III. METHODS AND PROCEDURES . -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Pearl Buck Is One of the Most Popular Novelists of Early Twentieth Century

ELK Asia Pacific Journals – Special Issue ISBN: 978-81-930411-2-3 TRAJECTORIES OF MULTICULTURAL CONSCIOUSNESS IN PEARL BUCK’S NOVEL ‘COME, MY BELOVED’ Dr.Jeyashree G.Iyer. Associate Professor/ HOD, English Department, Dr. Ambedkar College, Wadala. Mumbai. ABSTRACT: Pearl Buck is one of the most popular novelists of twentieth century. Her novel ‘The Good Earth’ fetched her Pulitzer Prize and the Howells medal in 1935. She was the first American woman to win Nobel Prize for Literature in 1938. Her father was in Christian Missionary who lived in China for forty two years to teach Christianity. Her visit to different countries facilitated her to infuse the essence of multiculturalism in her novels. Her novel ‘Come, My Beloved’ portrays colonial Indian society and duly records the religious confrontation of the east and the west. The dialectical presentation of the motif reveals the expertise of the novelist. The novel registers life journey of three generations of a rich American family, in India during colonial period. This paper attempts to exude how multicultural environment of India confuses a foreigner and also reveals how the west perceives Indian culture and society. Most part of the novel is engaged in intercultural dialogue illuminating clash of ideologies pertaining to culture and religion. The novel displays diverse points of view, plurality of descriptions of the same events. The theme of the novel is chronologically arranged highlighting cultural tensions prevail in India during colonial period. The theme is very relevant today as scholars and philosophers attempt to establish religious tolerance for better society. Pearl Buck’s sincere efforts to create the democratic utopia are lucidly evident but the novel ends with the blatant truth that social inequality and racial discrimination cannot be eradicated from a society easily. -

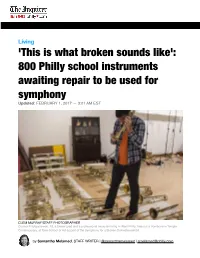

'This Is What Broken Sounds Like': 800 Philly School Instruments Awaiting Repair to Be Used for Symphony Updated: FEBRUARY 1, 2017 — 3:01 AM EST

Living 'This is what broken sounds like': 800 Philly school instruments awaiting repair to be used for symphony Updated: FEBRUARY 1, 2017 — 3:01 AM EST CLEM MURRAY/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER Connor Przybyszewski, 28, a Drexel grad and a professional musician living in West Philly, tries out a trombone in Temple Contemporary, at Tyler School of Art as part of the Symphony for a Broken Orchestra exhibit. by Samantha Melamed, STAFF WRITER | @samanthamelamed | [email protected] As a small corps of musicians arrived on a recent morning, Jeremy Thal gathered them into a loose huddle and laid out the day’s mission. “We know what one broken tuba sounds like,” he said. “Now, we’re kind of curious what four broken tubas sound like. So, everyone grab a horn that has a leak -- a sizable leak like this one, that’s missing a valve.” A half-hour later, a quartet was assembled: a French horn, 'This is what broken sounds like': approximately one-and-a-half trombones, and a French 800 Philly school instruments awaiting repair to be used for horn-meets- trumpet Frankenstein they were calling a symphony French hornet. “We’ll do two normal notes, and two notes of weirds,” Thal suggested. Then they played -- a sound that was a little bit Billie Holiday, a little bit pack of feral cats. This sonic strangeness is the result of a ragtag harvest from classrooms and storage spaces across the School District of Philadelphia, where a backlog of broken instruments has piled up since funding was slashed in 2013. Today, there are more than 800 of them out of a total instrument inventory of 10,000. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

Oprah's Book Club Titles

Oprah’s 1998 1996 Paradise by Toni Morrison The Deep End of the Ocean by Here on Earth by Alice Hoffman Jacquelyn Mitchard Book Club Black and Blue by Anna Quindlen Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison Breath, Eyes, Memory by Edwidge The Book of Ruth by Jane Hamilton Danticat She's Come Undone by Wally Lamb I Know This Much Is True by Wally titles Lamb What Looks Like Crazy on an Ordinary 1996 - 2010 Day by Pearl Cleage Midwives by Chris Bohjalian Where the Heart Is by Billie Letts 1997 Stones from the River by Ursula Hegi The Rapture of Canaan by Sheri Reynolds The Heart of a Woman by Maya Angelou Songs In Ordinary Time by Mary McGarry Morris The Meanest Thing To Say by Bill Cosby A Lesson Before Dying by Ernest J. Gaines Mount Vernon City Library Mount Vernon A Virtuous Woman by Kaye Gibbons 315 Snoqualmie Street Ellen Foster by Kaye Gibbons Mount Vernon, WA 9827 City Library The Treasure Hunt by Bill Cosby 360-336-6209 The Best Way To Play by Bill Cosby 2010 2005 2001 Freedom by Jonathan Franzen Light in August by William Faulkner We Were the Mulvaneys by Joyce Carol A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens The Sound and the Fury by William Oates Great Expectations by Charles Dickens Faulkner Icy Sparks by Gwyn Hyman Rubio As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner Stolen Lives: Twenty Years in a Desert A Million Little Pieces by James Frey Jail by Malika Oufkir 2009 Cane River by Lalita Tademy The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen Say You’re One of Them by Uwem 2004 A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry Akpan One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez The Heart is a Lonely Hunter 2008 by Carson McCullers 2000 A New Earth by Eckhart Tolle Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy Gap Creek by Robert Morgan The Story of Edgar Sawtelle by David The Good Earth by Pearl S.