OFFICIAL REPORT of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 27

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Report of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL — 5 February 1986 565 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 5 February 1986 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR EDWARD YOUDE, G.C.M.G., M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR DAVID AKERS-JONES, K.B.E., C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY SIR JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, K.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. MICHAEL DAVID THOMAS, C.M.G., Q.C. THE HONOURABLE LYDIA DUNN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEN SHOU-LUM, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER C. WONG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRADE AND INDUSTRY DR. THE HONOURABLE HO KAM-FAI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HU FA-KUANG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JOHN JOSEPH SWAINE, O.B.E., Q.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE STEPHEN CHEONG KAM-CHUEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG YAN-LUNG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MRS. SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE MARIA TAM WAI-CHU, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HENRIETTA IP MAN-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN NAI-KEONG, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR LANDS AND WORKS THE HONOURABLE CHAN YING-LUN, J.P. -

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL―26 October 1983 81

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL―26 October 1983 81 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 26 October 1983 The Council met at half past two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR EDWARD YOUDE, G.C.M.G., M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR CHARLES PHILIP HADDON-CAVE, K.B.E., C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY SIR JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, K.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. MICHAEL DAVID THOMAS, Q.C. THE HONOURABLE ROGERIO HYNDMAN LOBO, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE DENIS CAMPBELL BRAY, C.M.G., C.V.O., J.P. SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS THE HONOURABLE DAVID AKERS-JONES, C.M.G., J.P. SECRETARY FOR DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION THE HONOURABLE LO TAK-SHING, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRANCIS YUAN-HAO TIEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALEX WU SHU-CHIH, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEN SHOU-LUM, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LYDIA DUNN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALAN JAMES SCOTT, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRANSPORT THE HONOURABLE PETER C. WONG, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE THONG KAH-LEONG, C.B.E., J.P. DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRADE AND INDUSTRY THE HONOURABLE CHARLES YEUNG SIU-CHO, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JOHN MARTIN ROWLANDS, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE DR. THE HONOURABLE HO KAM-FAI, O.B.E., J.P. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 29

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 29 March 2001 4355 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Thursday, 29 March 2001 The Council met at half-past Two o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE MRS RITA FAN HSU LAI-TAI, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KENNETH TING WOO-SHOU, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TIEN PEI-CHUN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE DAVID CHU YU-LIN THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN IR DR THE HONOURABLE RAYMOND HO CHUNG-TAI, J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE MARTIN LEE CHU-MING, S.C., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ERIC LI KA-CHEUNG, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE DAVID LI KWOK-PO, J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRED LI WAH-MING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE NG LEUNG-SING 4356 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 29 March 2001 PROF THE HONOURABLE NG CHING-FAI THE HONOURABLE MARGARET NG THE HONOURABLE MRS SELINA CHOW LIANG SHUK-YEE, J.P. THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHEUNG MAN-KWONG THE HONOURABLE HUI CHEUNG-CHING THE HONOURABLE CHAN KWOK-KEUNG THE HONOURABLE CHAN YUEN-HAN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM THE HONOURABLE MRS SOPHIE LEUNG LAU YAU-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE SIN CHUNG-KAI THE HONOURABLE ANDREW WONG WANG-FAT, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PHILIP WONG YU-HONG THE HONOURABLE WONG YUNG-KAN THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE HOWARD YOUNG, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE YEUNG SUM THE HONOURABLE YEUNG YIU-CHUNG THE HONOURABLE LAU CHIN-SHEK, J.P. -

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 27 February 1985 671

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 27 February 1985 671 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 27 February 1985 The Council met at half past two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR EDWARD YOUDE, G.C.M.G., M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY (Acting) MR. DAVID AKERS-JONES, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY SIR JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, K.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. MICHAEL DAVID THOMAS, C.M.G., Q.C. THE HONOURABLE SIR ROGERIO HYNDMAN LOBO, C.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HARRY FANG SIN-YANG, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRANCIS YUAN-HAO TIEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALEX WU SHU-CHIH, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEN SHOU-LUM, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LYDIA DUNN, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER C. WONG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG LAM, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE THONG KAH-LEONG, C.B.E., J.P. DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRADE AND INDUSTRY DR. THE HONOURABLE HO KAM-FAI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALLEN LEE PENG-FEI, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW SO KWOK-WING, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE HU FA-KUANG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG PO-YAN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE DONALD LIAO POON-HUAI, C.B.E., J.P. -

OFFICIAL REPORT of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 25 April 1979 the Council Met at Half Past Two O'clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY the GO

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 25 April 1979 777 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 25 April 1979 The Council met at half past two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR CRAWFORD MURRAY MACLEHOSE, GBE, KCMG, KCVO THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR JACK CATER, KBE, JP THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY MR CHARLES PHILIP HADDON CAVE, CMG, JP THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR JOHN WILLIAM DIXON HOBLEY, CMG, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS MR LI FOOK-KOW, CMG, JP THE HONOURABLE DAVID AKERS-JONES, CMG, JP SECRETARY FOR THE NEW TERRITORIES THE HONOURABLE LEWIS MERVYN DAVIES, CMG, OBE, JP SECRETARY FOR SECURITY THE HONOURABLE DAVID WYLIE MCDONALD, CMG, JP DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS THE HONOURABLE KENNETH WALLIS JOSEPH TOPLEY, CMG, JP DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION THE HONOURABLE DAVID GREGORY JEAFFRESON, JP SECRETARY FOR ECONOMIC SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ALAN JAMES SCOTT, JP SECRETARY FOR HOUSING THE HONOURABLE EDWARD HEWITT NICHOLS, OBE, JP DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE AND FISHERIES THE HONOURABLE THOMAS LEE CHUN-YON, CBE, JP DIRECTOR OF SOCIAL WELFARE THE HONOURABLE DEREK JOHN CLAREMONT JONES, CMG, JP SECRETARY FOR THE ENVIRONMENT DR THE HONOURABLE THONG KAH-LEONG, JP DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, JP SECRETARY FOR SOCIAL SERVICES THE HONOURABLE JOHN MARTIN ROWLANDS, JP SECRETARY FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE 778 HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 25 April 1979 THE HONOURABLE JAMES NEIL HENDERSON, JP COMMISSIONER FOR LABOUR THE HONOURABLE OSWALD VICTOR CHEUNG, CBE, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE ROGERIO HYNDMAN LOBO, CBE, JP THE HONOURABLE JAMES WU MAN-HON, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE HILTON CHEONG-LEEN, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE LI FOOK-WO, CBE, JP THE HONOURABLE JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE LO TAK-SHING, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE ALEX WU SHU-CHIH, OBE, JP THE REV. -

28 July 1982 1073

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL―28 July 1982 1073 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 28 July 1982 The Council met at half past two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE ACTING GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR CHARLES PHILIP HADDON-CAVE, K.B.E., C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY MR. JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, O.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. JOHN CALVERT GRIFFITHS, Q.C. THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS (Acting) MR. DAVID AKERS-JONES, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE DAVID GREGORY JEAFFRESON, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR ECONOMIC SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ALAN JAMES SCOTT, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRANSPORT THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR SOCIAL SERVICES THE HONOURABLE JAMES NEIL HENDERSON, J.P. COMMISSIONER FOR LABOUR THE HONOURABLE JOHN MORRISON RIDDELL-SWAN, O.B.E., J.P. DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE AND FISHERIES THE HONOURABLE DONALD LIAO POON-HUAI, O.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR HOUSING THE HONOURABLE GRAHAM BARNES, J.P. REGIONAL SECRETARY (HONG KONG AND KOWLOON), CITY AND NEW TERRITORIES ADMINISTRATION THE HONOURABLE COLVYN HUGH HAYE, J.P. SECRETARY FOR EDUCATION (Acting) DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION THE HONOURABLE IAN FRANCIS CLUNY MACPHERSON, J.P. SECRETARY FOR CITY AND NEW TERRITORIES ADMINISTRATION (Acting) REGIONAL SECRETARY (NEW TERRITORIES), CITY AND NEW TERRITORIES ADMINISTRATION THE HONOURABLE MRS. ANSON CHAN, J.P. DIRECTOR OF SOCIAL WELFARE (Acting) THE HONOURABLE CHAN NAI-KEONG, J.P. SECRETARY FOR LANDS AND WORKS (Acting) DR. THE HONOURABLE LAM SIM-FOOK, O.B.E., J.P. -

OFFICIAL REPORT of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 26

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL―26 March 1980 609 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 26 March 1980 The Council met at half past two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR CRAWFORD MURRAY MACLEHOSE, G.B.E., K.C.M.G., K.C.V.O. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR JACK CATER, K.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY SIR CHARLES PHILIP HADDON-CAVE, K.B.E., C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. JOHN CALVERT GRIFFITHS, Q.C. THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS MR. LI FOOK-KOW, C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE DAVID AKERS-JONES, C.M.G., J.P. SECRETARY FOR THE NEW TERRITORIES THE HONOURABLE LEWIS MERVYN DAVIES, C.M.G., O.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR SECURITY THE HONOURABLE DAVID WYLIE McDONALD, C.M.G., J.P. DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS THE HONOURABLE KENNETH WALLIS JOSEPH TOPLEY, C.M.G., J.P. DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION THE HONOURABLE DAVID GREGORY JEAFFRESON, J.P. SECRETARY FOR ECONOMIC SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ALAN JAMES SCOTT, J.P. SECRETARY FOR HOUSING THE HONOURABLE THOMAS LEE CHUN-YON, C.B.E., J.P. DIRECTOR OF SOCIAL WELFARE THE HONOURABLE DEREK JOHN CLAREMONT JONES, C.M.G., J.P. SECRETARY FOR THE ENVIRONMENT DR. THE HONOURABLE THONG KAH-LEONG, C.B.E., J.P. DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, J.P. SECRETARY FOR SOCIAL SERVICES THE HONOURABLE JOHN CHARLES CREASEY WALDEN, J.P. DIRECTOR OF HOME AFFAIRS THE HONOURABLE JOHN MARTIN ROWLANDS, J.P. -

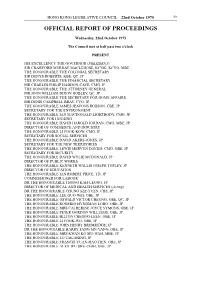

Official Report of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL—22nd October 1975 59 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 22nd October 1975 The Council met at half past two o'clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR CRAWFORD MURRAY MACLEHOSE, KCMG, KCVO, MBE THE HONOURABLE THE COLONIAL SECRETARY SIR DENYS ROBERTS, KBE, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY MR CHARLES PHILIP HADDON-CAVE, CMG, JP THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR JOHN WILLIAM DIXON HOBLEY, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS MR DENIS CAMPBELL BRAY, CVO, JP THE HONOURABLE JAMES JEAVONS ROBSON, CBE, JP SECRETARY FOR THE ENVIRONMENT THE HONOURABLE IAN MACDONALD LIGHTBODY, CMG, JP SECRETARY FOR HOUSING THE HONOURABLE DAVID HAROLD JORDAN, CMG, MBE, JP DIRECTOR OF COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY THE HONOURABLE LI FOOK-KOW, CMG, JP SECRETARY FOR SOCIAL SERVICES THE HONOURABLE DAVID AKERS-JONES, JP SECRETARY FOR THE NEW TERRITORIES THE HONOURABLE LEWIS MERVYN DAVIES, CMG, OBE, JP SECRETARY FOR SECURITY THE HONOURABLE DAVID WYLIE MCDONALD, JP DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS THE HONOURABLE KENNETH WALLIS JOSEPH TOPLEY, JP DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION THE HONOURABLE IAN ROBERT PRICE, TD, JP COMMISSIONER FOR LABOUR DR THE HONOURABLE THONG KAH-LEONG, JP DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES (Acting) DR THE HONOURABLE CHUNG SZE-YUEN, CBE, JP THE HONOURABLE LEE QUO-WEI, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE OSWALD VICTOR CHEUNG, OBE, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE ROGERIO HYNDMAN LOBO, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE MRS CATHERINE JOYCE SYMONS, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE PETER GORDON WILLIAMS, OBE, JP THE HONOURABLE HILTON CHEONG-LEEN, -

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 23 March 1983 659

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 23 March 1983 659 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 23 March 1983 The Council met at half past two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR EDWARD YOUDE, G.C.M.G., M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY (Acting) THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS MR. DENIS CAMPBELL BRAY, C.M.G., C.V.O., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY MR. JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, O.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. JOHN CALVERT GRIFFITHS, Q.C. THE HONOURABLE ROGERIO HYNDMAN LOBO, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE DAVID AKERS-JONES, C.M.G., J.P. SECRETARY FOR DISTRICT ADMINISTRATION THE HONOURABLE DAVID WYLIE MCDONALD, C.M.G., J.P. SECRETARY FOR LANDS AND WORKS DR. THE HONOURABLE HARRY FANG SIN-YANG, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LO TAK-SHING, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRANCIS YUAN-HAO TIEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE KENNETH WALLIS JOSEPH TOPLEY, C.M.G., J.P. SECRETARY FOR EDUCATION AND MANPOWER THE REVD. THE HONOURABLE JOYCE MARY BENNETT, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEN SHOU-LUM, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE HENRY HU HUNG-LICK, O.B.E., J.P. THE REVD. THE HONOURABLE PATRICK TERENCE MCGOVERN, O.B.E., S.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALAN JAMES SCOTT, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRANSPORT THE HONOURABLE PETER C. WONG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG LAM, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE THONG KAH-LEONG, C.B.E., J.P. -

Official Report of Proceedings

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL—10th August 1977 1181 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 10th August 1977 The Council met at half past two o'clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR CRAWFORD MURRAY MACLEHOSE, GBE, KCMG, KCVO THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY (Acting) MR CHARLES PHILIP HADDON-CAVE, CMG, JP THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY (Acting) MR DAVID GREGORY JEAFFRESON, JP THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR JOHN WILLIAM DIXON HOBLEY, CMG, QC, JP THE HONOURABLE THE SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS MR LI FOOK-KOW, CMG, JP THE HONOURABLE DAVID AKERS-JONES, JP SECRETARY FOR THE NEW TERRITORIES THE HONOURABLE LEWIS MERVYN DAVIES, CMG, OBE, JP SECRETARY FOR SECURITY THE HONOURABLE GARTH CECIL THORNTON, QC SOLICITOR GENERAL THE HONOURABLE THOMAS LEE CHUN-YON, CBE, JP DIRECTOR OF SOCIAL WELFARE DR THE HONOURABLE THONG KAH-LEONG, JP DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, JP SECRETARY FOR SOCIAL SERVICES THE HONOURABLE PETER BARRY WILLIAMS, JP COMMISSIONER FOR LABOUR THE HONOURABLE RONALD GEORGE BLACKOR BRIDGE, JP SECRETARY FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE THE HONOURABLE WILLIAM DORWARD, OBE, JP DIRECTOR OF TRADE, INDUSTRY & CUSTOMS (Acting) THE HONOURABLE COLVYN HUGH HAYE, JP DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION (Acting) THE HONOURABLE DONALD LIAO POON-HUAI, OBE, JP SECRETARY FOR HOUSING (Acting) THE HONOURABLE DAVID T. K. WONG, JP SECRETARY FOR ECONOMIC SERVICES (Acting) THE HONOURABLE WILLIAM COLLINS BELL, OBE, JP DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC WORKS (Acting) THE HONOURABLE GRAHAM BARNES, JP SECRETARY FOR THE ENVIRONMENT -

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 5 October 1983 9

HONG KONG LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ― 5 October 1983 9 OFFICIAL REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 5 October 1983 The Council met at half past two o’clock PRESENT HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR (PRESIDENT) SIR EDWARD YOUDE, G.C.M.G., M.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE CHIEF SECRETARY SIR CHARLES PHILIP HADDON-CAVE, K.B.E., C.M.G., J.P. THE HONOURABLE THE FINANCIAL SECRETARY SIR JOHN HENRY BREMRIDGE, K.B.E. THE HONOURABLE THE ATTORNEY GENERAL MR. MICHAEL DAVID THOMAS, Q.C. THE HONOURABLE ROGERIO HYNDMAN LOBO, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE DENIS CAMPBELL BRAY, C.M.G., C.V.O., J.P. SECRETARY FOR HOME AFFAIRS DR. THE HONOURABLE HARRY FANG SIN-YANG, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LO TAK-SHING, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FRANCIS YUAN-HAO TIEN, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALEX WU SHU-CHIH, C.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHEN SHOU-LUM, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LYDIA DUNN, C.B.E., J.P. THE REVD. THE HONOURABLE PATRICK TERENCE McGOVERN, O.B.E., S.J., J.P. THE HONOURABLE PETER C. WONG, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG LAM, O.B.E., J.P. DR. THE HONOURABLE THONG KAH-LEONG, C.B.E., J.P. DIRECTOR OF MEDICAL AND HEALTH SERVICES THE HONOURABLE ERIC PETER HO, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR TRADE AND INDUSTRY THE HONOURABLE CHARLES YEUNG SIU-CHO, O.B.E., J.P. THE HONOURABLE JOHN MARTIN ROWLANDS, C.B.E., J.P. SECRETARY FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE DR.