The Story of the Pine House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top of the World in the Style of Carpenters Mp3 Download

Top of the world in the style of carpenters mp3 download click here to download Watch the video for Top of the World from Carpenters's Love Songs for free, and see the artwork, lyrics and similar artists. Buy Top Of The World ( Remix): Read 36 Digital Music Reviews - Amazon. com. Read or print original Top Of The World lyrics updated! Such a feelin's comin' over me / There is wonder in most everything I see. "Top of the World" is a song written and composed by Richard Carpenter and John Bettis and first recorded by American pop duo the Carpenters. It was a . Download Top Of The World sheet music instantly - Piano (big note) sheet music by The Carpenters: Hal Leonard - Digital Sheet Music. Purchase, download. Buy the CD album for £ and get the MP3 version for FREE. .. The first CD is GOLD - the single song set of the Carpenters' hits. sounded fantastic - for me, she had (still has) one of the greatest singing voices the popular music world has The clothes also run the gamut from to - a lot of different styles. Find a Carpenters - MP3 first pressing or reissue. Complete MP3 (CD, CD- ROM, Compilation, Unofficial Release) album cover. More Images Genre: Jazz, Rock, Pop, Folk, World, & Country. Style: Pop Rock, Ballad, Vocal, Soft Rock, Easy Listening () A Song For You. 24, A Song For You. 25, Top Of The World. "Top Of The World" by The Carpenters ukulele tabs and chords. Album, A Song for You I'm on the top of the world lookin' down on creation C . -

Lycra, Legs, and Legitimacy: Performances of Feminine Power in Twentieth Century American Popular Culture

LYCRA, LEGS, AND LEGITIMACY: PERFORMANCES OF FEMININE POWER IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE Quincy Thomas A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Francisco Cabanillas, Graduate Faculty Representative Bradford Clark Lesa Lockford © 2018 Quincy Thomas All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor As a child, when I consumed fictional narratives that centered on strong female characters, all I noticed was the enviable power that they exhibited. From my point of view, every performance by a powerful character like Wonder Woman, Daisy Duke, or Princess Leia, served to highlight her drive, ability, and intellect in a wholly uncomplicated way. What I did not notice then was the often-problematic performances of female power that accompanied those narratives. As a performance studies and theatre scholar, with a decades’ old love of all things popular culture, I began to ponder the troubling question: Why are there so many popular narratives focused on female characters who are, on a surface level, portrayed as bastions of strength, that fall woefully short of being true representations of empowerment when subjected to close analysis? In an endeavor to answer this question, in this dissertation I examine what I contend are some of the paradoxical performances of female heroism, womanhood, and feminine aggression from the 1960s to the 1990s. To facilitate this investigation, I engage in close readings of several key aesthetic and cultural texts from these decades. While the Wonder Woman comic book universe serves as the centerpiece of this study, I also consider troublesome performances and representations of female power in the television shows Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the film Grease, the stage musical Les Misérables, and the video game Tomb Raider. -

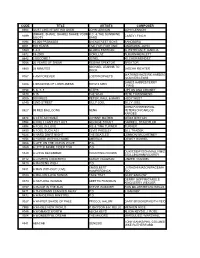

Code Title Artists Composer 8664 (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon John Lennon (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your K.C

CODE TITLE ARTISTS COMPOSER 8664 (JUST LIKE) STARTING OVER JOHN LENNON JOHN LENNON (SHAKE, SHAKE, SHAKE) SHAKE YOUR K.C. & THE SUNSHINE 8699 CASEY / FINCH BOOTY BAND 8094 10,000 PROMISES BACKSTREET BOYS SANDBERG 8001 100 YEARS FIVE FOR FIGHTING ONDRASIK, JOHN 8563 1-2-3 GLORIA ESTEFAN G. ESTEFAN/ E. GARCIA 8572 19-2000 GORILLAZ ALBARN/HEWLETT 8642 2 BECOME 1 JEWEL KILCHER/MENDEZ 9058 20 YEARS OF SNOW REGINA SPEKTOR SPEKTOR MICHAEL LEARNS TO 8865 25 MINUTES JASCHA RICHTER ROCK WATKINS/GAZE/RICHARDSO 8767 4 AM FOREVER LOSTPROPHETS N/OLIVER/LEWIS JAMES HARRIS/TERRY 8208 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS BOYZ II MEN LEWIS 9154 5, 6, 7, 8 STEPS LIPTON AND CROSBY 9370 5:15 THE WHO PETE TOWNSHEND 9005 500 MILES PETER, PAUL & MARY HEDY WEST 8140 52ND STREET BILLY JOEL BILLY JOEL JOEM FAHRENKROG- 8927 99 RED BALLOONS NENA PETERSON/CARLOS KARGES 8674 A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS WEBSTER/FAIN 8554 A FIRE I CAN'T PUT OUT GEORGE STRAIT DARRELL STAEDTLER 8594 A FOOL IN LOVE IKE & TINA TURNER TURNER 8455 A FOOL SUCH AS I ELVIS PRESLEY BILL TRADER 9224 A HARD DAY'S NIGHT THE BEATLES LENNON/ MCCARTNEY 8054 A HORSE WITH NO NAME AMERICA DEWEY BUNNEL 9468 A LIFE ON THE OCEAN WAVE P.D. 9469 A LITTLE MORE CIDER TOO P.D. DURITZ/BRYSON/MALLY/MIZ 8320 A LONG DECEMBER COUNTING CROWS E/GILLINGHAM/VICKREY 9112 A LOVER'S CONCERTO SARAH VAUGHAN LINZER / RANDEL 9470 A MAIDENS WISH P.D. ENGELBERT LIVRAGHI/MASON/PACE/MA 8481 A MAN WITHOUT LOVE HUMPERDINCK RIO 9183 A MILLION LOVE SONGS TAKE THAT GARY BARLOW GERRY GOFFIN/CAROLE 8073 A NATURAL WOMAN ARETHA FRANKLIN KING/JERRY WEXLER 9157 A PLACE IN THE SUN STEVIE WONDER RON MILLER/BRYAN WELLS 9471 A THOUSAND LEAGUES AWAY P.D. -

Peter Cincotti East of Angel Town

CD | DMD Peter Cincotti East Of Angel Town East Of Angel Town, the first album of HOMETOWN all original material from 25-year-old New York, NY singer-songwriter-pianist Peter Cincotti, PRODUCERS FEATURED TRACK teams him with l4-time Grammy® winning David Foster Goodbye Philadelphia producer David Foster, producer Jochem van der Saag SELECTIONS (TENTATIVE) Humberto Gatica, producer/sound Humberto Gatica Angel Town designer Jochem van der Saag—all of FILE UNDER Goodbye Philadelphia whom have worked with such stars as Pop Be Careful Josh Groban and Michael Bublé—and Cinderella Beautiful award-winning lyricist John Bettis RADIO FORMAT AC/Hot AC Make It Out Alive (Michael Jackson, Pointer Sisters, December Boys Madonna, Carpenters). Blending pop, ON THE WEB U B U rock, blues, funk and jazz, and marked by petercincotti.com Another Falling Star an expressive voice and prodigious piano myspace.com/petercincotti Broken Children talent, East Of Angel Town is the place warnerbrosrecords.com Man On A Mission where mainstream music fans will finally STREET DATE Always Watching You discover Peter Cincotti. 1/13/09 Witch’s Brew The Country Life I SINGLE/VIDEO: “Goodbye Philadelphia” is the Love Is Gone first single. A video is available as well. Come Tomorrow I PUBLICITY: Radio events for AC stations and high profile TV appearances will support the CD’s release. I TOUR: Plans for a spring tour are underway. I RECENT SUCCESS: The album and single saw huge success with Top 100 hits throughout Europe. I HISTORY: After touring with Harry Connick, Jr., and appearing at the Montreux Jazz Festival, Cincotti at age 18 became the youngest performer to headline the prestigious Oak Room of the Algonquin Hotel in New York. -

Skinny Blues: Karen Carpenter, Anorexia Nervosa and Popular Music

Skinny blues: Karen Carpenter, anorexia nervosa and popular music George McKay We might locate that colloquial inauguration of anorexia on a Las Vegas nightclub stage in the fall of 1975, when the popular musician Karen Carpenter collapsed while singing ‘Top of the world’; or on the morning of 5 February 1983, when news [broke] of Carpenter’s death from a ‘starvation diet’…. [I]n the 1970s and 1980s [anorexia] … became a vernacular, an everyday word, an idiom. Patrick Anderson, So Much Wasted (2010, 32) The words come out of yr mouth but yr eyes say other things, ‘Help me, please, I’m lost in my own passive resistance, something went wrong’…. Did anyone ever ask you that question—what’s it like being a girl in music? Kim Gordon, ‘Open letter to Karen’ (n.d.) This article discusses an extraordinary body (Thomson 1997) in popular music, that belonging to the person with anorexia which is also usually a gendered body—female—and that of the singer or frontperson. I explore the relation between the anorexic body and popular music, which is more than simply looking at constructions of anorexia in pop. It involves contextually thinking about the (medical) history and the critical reception and representation, the place of anorexia across the creative industries more widely, and a particular moment when pop played a role in the public awareness of anorexia. Following such context I will look in more detail at a small number of popular music artists who had experience of anorexia, their stage and media presentations (of it), and how they did or apparently did not explore their experience of it in their own work and public appearances. -

Pre-Owned 1970S Sheet Music

Pre-owned 1970s Sheet Music 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 PLEASE NOTE THE FOLLOWING FOR A GUIDE TO CONDITION AND PRICES PER TITLE ex No marks or deterioration Priced £15. good As appropriate for age of the manuscript. Slight marks on front cover (shop stamp or owner's name). Possible slight marking (pencil) inside. Priced £12. fair Some damage such as edging tears. Reasonable for age of manuscript. Priced £5 Album Contains several songs and photographs of the artist(s). Priced £15+ condition considered. Year Year of print. Usually the same year as copyright (c) but not always. Photo Artist(s) photograph on front cover. n/a No artist photo on front cover LOOKING FOR THESE ARTISTS? You’ve come to the right place for The Bee Gees, Eric Clapton, Russ Conway, John B.Sebastian, Status Quo or even Wings or “Woodstock”. Just look for the artist’s name on the lists below. 1970s TITLE WRITER & COMPOSER CONDITION PHOTO YEAR $7,000 and you Hugo & Luigi/George David Weiss ex The Stylistics 1977 ABBA – greatest hits Album of 19 songs from ex Abba © 1992 B.Andersson/B.Ulvaeus After midnight John J.Cale ex Eric Clapton 1970 After the goldrush Neil Young ex Prelude 1970 Again and again Richard Parfitt/Jackie Lynton/Andy good Status Quo 1978 Bown Ain’t no love John Carter/Gill Shakespeare ex Tom Jones 1975 Airport Andy McMaster ex The Motors 1976 Albertross Peter Green fair Fleetwood Mac 1970 Albertross (piano solo) Peter Green ex n/a ©1970 All around my hat Hart/Prior/Knight/Johnson/Kemp ex Steeleye Span 1975 All creatures great and -

Thriller” (1982) by Michael Jackson (1982) Added to the National Recording: 2007 Essay by Joe Vogel (Guest Post)*

“Thriller” (1982) by Michael Jackson (1982) Added to the National Recording: 2007 Essay by Joe Vogel (guest post)* Original album Original label Michael Jackson Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” changed the trajectory of music—the way it sounded, the way it felt, the way it looked, the way it was consumed. Only a handful of albums come anywhere close to its seismic cultural impact: the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper,” Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon,” Nirvana’s “Nevermind.” Yet “Thriller” remains, by far, the best-selling album of all time. Current estimates put U.S. sales at close to 35 million, and global sales at over 110 million. Its success is all the more remarkable given the context. In 1982, the United States was still in the midst of a deep recession as unemployment reached a four-decade high (10.8 percent). Record companies were laying people off in droves. Top 40 radio had all but died, as stale classic rock (AOR) dominated the airwaves. Disco had faded. MTV was still in its infancy. As “The New York Times” puts it: “There had never been a bleaker year for pop than 1982.” And then came “Thriller.” The album hit record stores in the fall of ‘82. It’s difficult to get beyond the layers of accolades and imagine the sense of excitement and discovery for listeners hearing it for the first time--before the music videos, before the stratospheric sales numbers and awards, before it became ingrained in our cultural DNA. The compact disc (CD) was made commercially available that same year, but the vast majority of listeners purchased the album as an LP or cassette tape (the latter of which outsold records by 1983). -

Proof of Mechanical Music Licensing

11/30/2017 Proof of Licensing November 30, 2017 PROOF OF MECHANICAL MUSIC LICENSING Acting as a licensing agent, Legacy Productions Inc. d/b/a Easy Song Licensing ("ESL") has acquired Compulsory Mechanical Licenses on behalf of the licensee for each song below marked "Licensed". The licenses cover the format and quantity for the specified release only, identified by the unique Release ID: Release ID: LPL032364 (cover-song-project.aspx?p=32364) Artist: Angelina Graziano-Straus Title: HOPE (for the Angel In A Rose Project) Format: 1,000 Compact Discs Date: April, 2016 Licensee Laura Graziano PO Box 425 Harvard, Illinois 60033 United States License # Song Status 108848 Because You Loved Me Licensed By Diane Warren Copyright Realsongs And Touchstone Pictures Music & Songs, Inc. 108839 I Will Always Love You Licensed By Dolly Parton Copyright Velvet Apple Music 108840 The Prayer Licensed By Carole Sager, David Foster, Alberto Testa, and Tony Renis Copyright 1998, Songs Of Universal, Inc Obo Warner-Barham Music, Llc And S.I.A.E. Direzione Generale https://www.easysonglicensing.com/pages/account/projects/cover-songs/proof-of-licensing.aspx?p=32364 1/3 11/30/2017 Proof of Licensing 108841 At Last Licensed By Mack Gordon and Harry Warren Copyright Emi Feist Catalog Inc 108842 One Moment in Time Licensed By John Bettis and Albert Hammond Copyright Albert Hammond Music, Bettis John Music And W B Music Corp 108844 The Star Spangled Banner Licensed By Francis Scott Key and John Stafford Smith Arranged by Henry Fillmore Copyright Carl Fischer, Llc 108845 When You Believe Licensed By Kenneth Babyface Edmonds and Stephen Lawrence Schwartz Copyright Almo Music Corp. -

SWV Best of SWV Mp3, Flac, Wma

SWV Best Of SWV mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop / Funk / Soul Album: Best Of SWV Country: Europe Released: 2001 Style: RnB/Swing, Rhythm & Blues, Soul, Funk, New Jack Swing, Contemporary R&B MP3 version RAR size: 1793 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1412 mb WMA version RAR size: 1944 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 719 Other Formats: FLAC TTA DXD MMF MP1 MP3 WAV Tracklist Hide Credits Anything 1 2:48 Producer, Written-By – Brian Alexander Morgan Right Here (Human Nature Radio Mix) Performer ["Human Nature" Excerpt] – Michael JacksonProducer, Written-By – Brian 2 3:49 Alexander MorganRemix – Teddy RileyWritten-By ["Human Nature" Excerpt] – John Bettis, Steve Porcaro Weak 3 4:54 Producer, Written-By – Brian Alexander Morgan What's It Gonna Be 4 4:34 Producer, Written-By – Brian Alexander Morgan It's All About U 5 Producer – Allen "Allstar" Gordon Jr.*Producer [Additional] – Anthony "Reezmo" 3:46 Burroughs*Written-By – Allstar*, Andrea Martin, Anthony "Reezmo" Burroughs* When U Cry 6 Producer – Kevin Perez, A.D. Perez*Written-By – D. Ellis*, Kevin Perez, Patricia Deige 4:36 Muldrow, P. Richmond*, L. Rocke Jr.*, A.D. Perez* I'm So Into You 7 4:41 Producer, Written-By – Brian Alexander Morgan You're Always On My Mind 8 5:20 Producer, Written-By – Brian Alexander Morgan Someone Featuring – Puff DaddyPerformer ["Ten Crack Commandments" & "The World Is Filled" Samples] – The Notorious B.I.G.*Producer – Jay Dub, Sean "Puffy" Combs*Producer 9 [Additional] – Steven "Stevie J." Jordan*Producer [Vocals] – Kelly Price, Troy TaylorWritten- 4:09 By – C. Martin*, C. -

Tkr300 Built-In Songs

Page 1 of 29 TKR300 BUILT-IN SONGS TITLE TKR-300CE POPULARIZED BY COMPOSER/LYRICST Song Type BREATHLESS 115 THE CORRS The Corrs,M.Lange Realsound BRIDGE OVER TROUBLED WATER 111 SIMON & GARFUNKEL Paul Simon Realsound CAN'T HELP FALLING IN LOVE 102 ELVIS PRESLEY G.Weiss/Creatore/Peretti Realsound DIANA 110 PAUL ANKA Paul Anka Realsound DON'T CHA 114 PUSSYCAT DOLLS T.Smith,A.Ray,T.Callaway Realsound GREATEST LOVE OF ALL 108 WHITNEY HOUSTON M.Masser/L.Epstein Realsound I JUST CALLED TO SAY I LOVE YOU 112 STEVIE WONDER S.Wonder Realsound LET ME BE THERE 104 OLIVIA NEWTON JOHN J.Rostill Realsound LET'S GET IT STARTED 101 BLACK EYED PEAS Adams/Ferguson/Indivar/Shah/Charles/George/Boar d/Clarke Realsound PUSH THE BUTTON 113 SUGABABES Sugababes/D.austin Realsound TAKE ME HOME COUNTRY ROAD 107 JOHN DENVER John Denver Realsound TOP OF THE WORLD 105 CARPENTERS J.Bettis/R.Carpenter Realsound Y. M. C. A. 109 VILLAGE PEOPLE Morali,Belolo,Willis Realsound YESTERDAY ONCE MORE 106 CARPENTERS J.Bettis/R.Carpenter Realsound YOU MEAN EVERYTHING TO ME 103 NEIL SEDAKA H. Greenfield, N. Sedaka Realsound (I CAN'T GET NO) SATISFACTION 11161 THE ROLLING STONES Michael Jagger / Keith Richard (I JUST) DIED IN YOUR ARMS 10293 CUTTING CREW Nicholas Eede (I'VE HAD) THE TIME OF MY LIFE 10116 BILL MEDLEY Denicola/Markowitz/Previte (THERE'S GOTTA BE)MORE TO LIFE 10998 STACIE ORRICO Breer/Mason/Kadish/Thomas/Woodward 1979 10988 SMASHING PUMPKINS Corgan William Patrick 2 BECOME 1 10992 SPICE GIRLS Spice Girls/Stannard/Rowe 25 MINUTES 10732 MICHAEL LEARNS TO ROCK Jascha Richter 25 OR 6 TO 4 10244 CHICAGO Robert Lamm 4 SEASONS OF LONELINESS 10164 BOYZ II MEN Jjam, T. -

The Hustler Photo Staff

TODAY’s WEATHER LIFE SPORTS Find out the best acts to The Sports staff continues its see at Bonnaroo baseball preview, profiles new SEE PAGE 6 players SEE PAGE 7 Mostly sunny 60 / 50 THE VANDERBILT HUSTLER THE VOICE OF VANDERBILT SINCE 1888 WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 2011 WWW .INSIDEVANDY.COM 123RD YEAR, NO. 19 ADMINISTRATION MUSIC Rites of Spring, the most highly- anticipated weekend of the spring semester, will take place April 15-16 this year. The Life Section has taken the guesswork out of this year’s festival by reviewing headliners Kid Cudi and The National, along with the entire lineup. OLIVER WOLFE/ The Vanderbilt Hustler From girly pop-rocker Sara Bareilles to Senior Ben Eagles looks on as a speaker discusses contract negotia- the eclectic sound of Edward Sharpe tions Thursday night at the Vanderbilt Student/Worker Fellowship. & The Magnetic Zeros, Rites of Spring Administration, 2011 won’t disappoint. union struggle THE NATIONAL BENJAMIN RIES to find common Staff Writer The National may seem at first like ground in contract an odd group to headline an outdoor concert: Their last three albums — all masterpieces — create immersive, negotiations hazy atmospheres filled with lyrics that deal with themes of emotional confusion and self-doubt. However, LUCAS LOFFREDO “They’re basically telling us as with their influences — chiefly Joy Staff Writer that they don’t want to meet Division and Bruce Springsteen — with us twice a week,” said The National’s songs take on a new SUSANNA HOWE/Photo Provided Contract negotiations have Union Steward John Webb. form live. The National’s performance effectively come to a standstill “They want to bring a mediator at the Ryman Auditorium last fall ex- ming to create a melancholy combi- blatant political commentary as an between Vanderbilt and its in because we’re so far apart on emplified this on-stage fervor with nation of post-punk and indie rock. -

Skinny Blues: Karen Carpenter, Anorexia Nervosa and Popular Music

Popular Music (2018) Volume 37/1. © Cambridge University Press 2017, pp. 1–21 doi:10.1017/S026114301700054X Skinny blues: Karen Carpenter, anorexia nervosa and popular music GEORGE McKAY Film Television & Media Studies, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article discusses an extraordinary body in popular music, that belonging to the person with anorexia which is also usually a gendered body – female – and that of the singer or frontperson. I explore the relation between the anorexic body and popular music, which is more than simply look- ing at constructions of anorexia in pop. It involves contextually thinking about the (medical) history and the critical reception and representation, the place of anorexia across the creative industries more widely, and a particular moment when pop played a role in the public awareness of anorexia. Following such context the article looks in more detail at a small number of popular music artists who had experience of anorexia, their stage and media presentations (of it), and how they did or apparently did not explore their experience of it in their own work and public appearances. This close discussion is framed within thinking about the popular music industry’s capacity for careless- ness, its schedule of pressure and practice of destruction on its own stars, particularly in this instance its female artists. This is an article about a condition and an industry. At its heart is the American singer and drummer Karen Carpenter (1950–1983), a major international pop star in the 1970s, in the Carpenters duo with her brother Richard; the other figures discussed are Scottish child pop star Lena Zavaroni (1963–1999), and the Welsh rock lyricist, stylist and erstwhile guitarist of the Manic Street Preachers, Richey Edwards (1967–1995 missing/2008 officially presumed dead).