Vera C. Rubin (1928-2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April Constellations of the Month

April Constellations of the Month Leo Small Scope Objects: Name R.A. Decl. Details M65! A large, bright Sa/Sb spiral galaxy. 7.8 x 1.6 arc minutes, magnitude 10.2. Very 11hr 18.9m +13° 05’ (NGC 3623) high surface brighness showing good detail in medium sized ‘scopes. M66! Another bright Sb galaxy, only 21 arc minutes from M65. Slightly brighter at mag. 11hr 20.2m +12° 59’ (NGC 3627) 9.7, measuring 8.0 x 2.5 arc minutes. M95 An easy SBb barred spiral, 4 x 3 arc minutes in size. Magnitude 10.5, with 10hr 44.0m +11° 42’ a bright central core. The bar and outer ring of material will require larger (NGC 3351) aperature and dark skies. M96 Another bright Sb spiral, about 42 arc minutes east of M95, but larger and 10hr 46.8m +11° 49’ (NGC 3368) brighter. 6 x 4 arc minutes, magnitude 10.1. Located about 48 arc minutes NNE of M96. This small elliptical galaxy measures M105 only 2 x 2.1 arc minutes, but at mag. 10.3 has very high surface brightness. 10hr 47.8m +12° 35’ (NGC 3379) Look for NGC 3384! (110NGC) and NGC 3389 (mag 11.0 and 12.2) which form a small triangle with M105. NGC 3384! 10hr 48.3m +12° 38’ See comment for M105. The brightest galaxy in Leo, this Sb/Sc spiral galaxy shines at mag. 9.5. Look for NGC 2903!! 09hr 32.2m +21° 30’ a hazy patch 11 x 4.7 arc minutes in size 1.5° south of l Leonis. -

David Kirkby University of California, Irvine, USA 4 August 2020 Expanding Universe

COSMOLOGY IN THE 2020S David Kirkby University of California, Irvine, USA 4 August 2020 Expanding Universe... 2 expansion history a(t |Ωm, ΩDE, …) 3 4 redshift 5 6 0.38Myr opaque universe last scatter 7 inflation opaque universe last scatter gravity waves? 8 CHIME SPT-3G DES 9 TCMB=2.7K, λ~2mm 10 CMB TCMB=2.7K, λ~2mm Galaxies 11 microwave projects: cosmic microwave background (primordial gravity waves, neutrinos, ...) CMB Galaxies optical & NIR projects: galaxy surveys (dark energy, neutrinos, ...) 12 CMB Galaxies telescope location: ground / above atmosphere 13 CMB Atacama desert, Chile CMB ground telescope location: Atacama desert / South Pole 14 Galaxies Galaxy survey instrument: spectrograph / imager 15 Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) Vera Rubin Observatory 16 Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) Vera Rubin Observatory 17 EXPANSION HISTORY VS STRUCTURE GROWTH Measurements of our cosmic expansion history constrain the parameters of an expanding homogenous universe: SN LSS , …) expansion historyDE m, Ω a(t |Ω CMB Small inhomogeneities are growing against this backdrop. Measurements of this structure growth provide complementary constraints. 18 Structure Growth 19 Redshift is not a perfect proxy for distance because of galaxy peculiar motions. Large-scale redshift-space distortions (RSD) trace large-scale matter fluctuations: signal! 20 Angles measured on the sky are also distorted by weak lensing (WL) as light is deflected by the same large-scale matter fluctuations: signal! Large-scale redshift-space distortions (RSD) trace large-scale matter fluctuations: signal! 21 CMB measures initial conditions of structure growth at z~1090: Temperature CMB photons also experience weak lensing! https://wiki.cosmos.esa.int/planck-legacy-archive/index.php/CMB_maps Polarization 22 CMB: INFLATION ERA SIGNATURES https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-astro-081915-023433 lensing E-modes lensing B-modes GW B-modes https://arxiv.org/abs/1907.04473 Lensing B modes already observed. -

A New Universe to Discover: a Guide to Careers in Astronomy

A New Universe to Discover A Guide to Careers in Astronomy Published by The American Astronomical Society What are Astronomy and Astrophysics? Ever since Galileo first turned his new-fangled one-inch “spyglass” on the moon in 1609, the popular image of the astronomer has been someone who peers through a telescope at the night sky. But astronomers virtually never put eye to lens these days. The main source of astronomical data is still photons (particles of light) from space, but the tools used to gather and analyze them are now so sophisticated that it’s no longer necessary (or even possible, in most cases) for a human eye to look through them. But for all the high-tech gadgetry, the 21st-Century astronomer is still trying to answer the same fundamental questions that puzzled Galileo: How does the universe work, and where did it come from? Webster’s dictionary defines “astronomy” as “the science that deals with the material universe beyond the earth’s atmosphere.” This definition is broad enough to include great theoretical physicists like Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, and Stephen Hawking as well as astronomers like Copernicus, Johanes Kepler, Fred Hoyle, Edwin Hubble, Carl Sagan, Vera Rubin, and Margaret Burbidge. In fact, the words “astronomy” and “astrophysics” are pretty much interchangeable these days. Whatever you call them, astronomers seek the answers to many fascinating and fundamental questions. Among them: *Is there life beyond earth? *How did the sun and the planets form? *How old are the stars? *What exactly are dark matter and dark energy? *How did the Universe begin, and how will it end? Astronomy is a physical (non-biological) science, like physics and chemistry. -

What Happened Before the Big Bang?

Quarks and the Cosmos ICHEP Public Lecture II Seoul, Korea 10 July 2018 Michael S. Turner Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics University of Chicago 100 years of General Relativity 90 years of Big Bang 50 years of Hot Big Bang 40 years of Quarks & Cosmos deep connections between the very big & the very small 100 years of QM & atoms 50 years of the “Standard Model” The Universe is very big (billions and billions of everything) and often beyond the reach of our minds and instruments Big ideas and powerful instruments have enabled revolutionary progress a very big idea connections between quarks & the cosmos big telescopes on the ground Hawaii Chile and in space: Hubble, Spitzer, Chandra, and Fermi at the South Pole basics of our Universe • 100 billion galaxies • each lit with the light of 100 billion stars • carried away from each other by expanding space from a • big bang beginning 14 billion yrs ago Hubble (1925): nebulae are “island Universes” Universe comprised of billions of galaxies Hubble Deep Field: one ten millionth of the sky, 10,000 galaxies 100 billion galaxies in the observable Universe Universe is expanding and had a beginning … Hubble, 1929 Signature of big bang beginning Einstein: Big Bang = explosion of space with galaxies carried along The big questions circa 1978 just two numbers: H0 and q0 Allan Sandage, Hubble’s “student” H0: expansion rate (slope age) q0: deceleration (“droopiness” destiny) … tens of astronomers working (alone) to figure it all out Microwave echo of the big bang Hot MichaelBig S Turner Bang -

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC by Paul Dickson Version: 1.4 | March 26, 1997 Copyright °c 1996, by Paul Dickson. All rights reserved If you purchased this book from Paul Dickson directly, please ignore this form. I already have most of this information. Why Should You Register This Book? Please register your copy of this book. I have done two book, SAC's 110 Best of the NGC and the Messier Logbook. In the works for late 1997 is a four volume set for the Herschel 400. q I am a beginner and I bought this book to get start with deep-sky observing. q I am an intermediate observer. I bought this book to observe these objects again. q I am an advance observer. I bought this book to add to my collect and/or re-observe these objects again. The book I'm registering is: q SAC's 110 Best of the NGC q Messier Logbook q I would like to purchase a copy of Herschel 400 book when it becomes available. Club Name: __________________________________________ Your Name: __________________________________________ Address: ____________________________________________ City: __________________ State: ____ Zip Code: _________ Mail this to: or E-mail it to: Paul Dickson 7714 N 36th Ave [email protected] Phoenix, AZ 85051-6401 After Observing the Messier Catalog, Try this Observing List: SAC's 110 Best of the NGC [email protected] http://www.seds.org/pub/info/newsletters/sacnews/html/sac.110.best.ngc.html SAC's 110 Best of the NGC is an observing list of some of the best objects after those in the Messier Catalog. -

Beyond Einstein

QuarksQuarks toto thethe Cosmos:Cosmos: the deep connections between the largest and smallest scales in the Universe ScalesScales ofof thethe UniverseUniverse LectureLecture SeriesSeries 16 November 2007 Michael S. Turner Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics The UniversityMichael S Turner of Chicago Full Scale Model of Universe a Fraction of a Second After the Beginning Amazing as it is, the connections go far beyond the fact that it began as Quark Soup NB: No deep connections between quarks and chemistry even though are made of quarks! ••TheThe AtomsAtoms wewe andand thethe starsstars ofof mademade ofof ••TheThe DarkDark MatterMatter thatthat holdsholds thethe UniverseUniverse togethertogether ••TheThe DarkDark EnergyEnergy thatthat isis causingcausing thethe expansionexpansion ofof thethe UniverseUniverse toto speedspeed upup ••TheThe SeedsSeeds ofof allall structuresstructures (clusters,(clusters, galaxies,galaxies, stars,stars, ……)) TheThe UniverseUniverse isis gettinggetting biggerbigger –– expandingexpanding ExpandingExpanding UniverseUniverse isis expandingexpanding spacespace • Hubble’s law (correlation between velocity and distance) • Redshift of light • General relativity NoNo CenterCenter JustJust DifferentDifferent PerspectivesPerspectives EvidenceEvidence forfor HotHot BigBig BangBang • Expansion of Universe • Cosmic microwave background: microwave echo of big bang • Abundance of the elements H, D, He, Li • Consistent age: expansion age, oldest stars, age of radioactive elements, cooling of white dwarf stars, age of oldest -

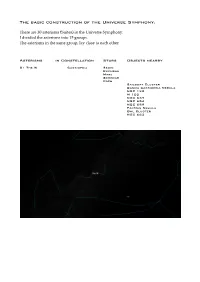

00E the Construction of the Universe Symphony

The basic construction of the Universe Symphony. There are 30 asterisms (Suites) in the Universe Symphony. I divided the asterisms into 15 groups. The asterisms in the same group, lay close to each other. Asterisms!! in Constellation!Stars!Objects nearby 01 The W!!!Cassiopeia!!Segin !!!!!!!Ruchbah !!!!!!!Marj !!!!!!!Schedar !!!!!!!Caph !!!!!!!!!Sailboat Cluster !!!!!!!!!Gamma Cassiopeia Nebula !!!!!!!!!NGC 129 !!!!!!!!!M 103 !!!!!!!!!NGC 637 !!!!!!!!!NGC 654 !!!!!!!!!NGC 659 !!!!!!!!!PacMan Nebula !!!!!!!!!Owl Cluster !!!!!!!!!NGC 663 Asterisms!! in Constellation!Stars!!Objects nearby 02 Northern Fly!!Aries!!!41 Arietis !!!!!!!39 Arietis!!! !!!!!!!35 Arietis !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1056 02 Whale’s Head!!Cetus!! ! Menkar !!!!!!!Lambda Ceti! !!!!!!!Mu Ceti !!!!!!!Xi2 Ceti !!!!!!!Kaffalijidhma !!!!!!!!!!IC 302 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 990 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1024 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1026 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1070 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1085 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1107 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1137 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1143 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1144 !!!!!!!!!!NGC 1153 Asterisms!! in Constellation Stars!!Objects nearby 03 Hyades!!!Taurus! Aldebaran !!!!!! Theta 2 Tauri !!!!!! Gamma Tauri !!!!!! Delta 1 Tauri !!!!!! Epsilon Tauri !!!!!!!!!Struve’s Lost Nebula !!!!!!!!!Hind’s Variable Nebula !!!!!!!!!IC 374 03 Kids!!!Auriga! Almaaz !!!!!! Hoedus II !!!!!! Hoedus I !!!!!!!!!The Kite Cluster !!!!!!!!!IC 397 03 Pleiades!! ! Taurus! Pleione (Seven Sisters)!! ! ! Atlas !!!!!! Alcyone !!!!!! Merope !!!!!! Electra !!!!!! Celaeno !!!!!! Taygeta !!!!!! Asterope !!!!!! Maia !!!!!!!!!Maia Nebula !!!!!!!!!Merope Nebula !!!!!!!!!Merope -

High-Resolution Measurements of the Halos of Four Dark Matter

Accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal A Preprint typeset using LTEX style emulateapj v. 6/22/04 HIGH-RESOLUTION MEASUREMENTS OF THE HALOS OF FOUR DARK MATTER-DOMINATED GALAXIES: DEVIATIONS FROM A UNIVERSAL DENSITY PROFILE1 Joshua D. Simon2, Alberto D. Bolatto2, Adam Leroy2, and Leo Blitz Department of Astronomy, 601 Campbell Hall, University of California at Berkeley, CA 94720 and Elinor L. Gates Lick Observatory, P.O. Box 85, Mount Hamilton, CA 95140 Accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal ABSTRACT We derive rotation curves for four nearby, low-mass spiral galaxies and use them to constrain the shapes of their dark matter density profiles. This analysis is based on high-resolution two-dimensional Hα velocity fields of NGC 4605, NGC 5949, NGC 5963, and NGC 6689 and CO velocity fields of NGC 4605 and NGC 5963. In combination with our previous study of NGC 2976, the full sample of five galaxies contains density profiles that span the range from αDM =0 to αDM =1.20, where αDM is the power law index describing the central density profile. The scatter in αDM from galaxy to galaxy is 0.44, three times as large as in Cold Dark Matter (CDM) simulations, and the mean density profile slope is αDM =0.73, shallower than that predicted by the simulations. These results call into question the hypothesis that all galaxies share a universal dark matter density profile. We show that one of the galaxies in our sample, NGC 5963, has a cuspy density profile that closely resembles those seen in CDM simulations, demonstrating that while galaxies with the steep central density cusps predicted by CDM do exist, they are in the minority. -

Center for History of Physics Newsletter, Spring 2008

One Physics Ellipse, College Park, MD 20740-3843, CENTER FOR HISTORY OF PHYSICS NIELS BOHR LIBRARY & ARCHIVES Tel. 301-209-3165 Vol. XL, Number 1 Spring 2008 AAS Working Group Acts to Preserve Astronomical Heritage By Stephen McCluskey mong the physical sciences, astronomy has a long tradition A of constructing centers of teaching and research–in a word, observatories. The heritage of these centers survives in their physical structures and instruments; in the scientific data recorded in their observing logs, photographic plates, and instrumental records of various kinds; and more commonly in the published and unpublished records of astronomers and of the observatories at which they worked. These records have continuing value for both historical and scientific research. In January 2007 the American Astronomical Society (AAS) formed a working group to develop and disseminate procedures, criteria, and priorities for identifying, designating, and preserving structures, instruments, and records so that they will continue to be available for astronomical and historical research, for the teaching of astronomy, and for outreach to the general public. The scope of this charge is quite broad, encompassing astronomical structures ranging from archaeoastronomical sites to modern observatories; papers of individual astronomers, observatories and professional journals; observing records; and astronomical instruments themselves. Reflecting this wide scope, the members of the working group include historians of astronomy, practicing astronomers and observatory directors, and specialists Oak Ridge National Laboratory; Santa encounters tight security during in astronomical instruments, archives, and archaeology. a wartime visit to Oak Ridge. Many more images recently donated by the Digital Photo Archive, Department of Energy appear on page 13 and The first item on the working group’s agenda was to determine through out this newsletter. -

![[Your Letterhead Here]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3105/your-letterhead-here-1973105.webp)

[Your Letterhead Here]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Dr. Bruce Elmegreen, of IBM Research, to receive the 2021 Bruce Gold Medal The Astronomical Society of the Pacific (ASP) is proud to announce the 2021 recipient of its most prestigious award, the Catherine Wolfe Bruce Gold Medal honoring Dr. Bruce Elmegreen, in recognition of his pioneering work on dynamical processes of star formation. SAN FRANCISCO, California – August 24, 2021 After four decades of innovative research, Dr. Elmegreen has fundamentally changed our understanding of star formation. He studied widespread hierarchical structure in young stellar regions, discovered that star formation is rapid following turbulent compression and gravitational collapse of these regions, explained the formation of stellar clusters, and discovered the largest scales for these processes in galaxies beyond our own, spanning a wide range of cosmic time. Elmegreen was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and received a B.S. in Physics and Astronomy from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He earned his PhD at Princeton University under the guidance of Lyman Spitzer, Jr. (Bruce Medal awardee, 1973), studying the ionization of the local interstellar medium. His interests turned to interstellar dynamics as a Junior Fellow at Harvard University, where, together with a colleague, he proposed that ionization from one generation of stars can compress residual gas and form another generation. He followed that with observations of interstellar filaments as further evidence for triggered collapse and proposed the same process on the scale of spiral arms. General observations and acceptance of these ideas would take several decades. After six years on the faculty of Columbia University in the City of New York, Elmegreen moved to IBM Research in 1984 where he began studies of galactic spirals, making the first digitized color images of galaxies and examining their symmetries to find spiral modes. -

![Arxiv:2108.02207V1 [Astro-Ph.CO] 4 Aug 2021 Without Many Localised FRB Sources [26]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1429/arxiv-2108-02207v1-astro-ph-co-4-aug-2021-without-many-localised-frb-sources-26-2051429.webp)

Arxiv:2108.02207V1 [Astro-Ph.CO] 4 Aug 2021 Without Many Localised FRB Sources [26]

Cosmology with the moving lens effect Selim C. Hotinli,1 Kendrick M. Smith,2 Mathew S. Madhavacheril,2 and Marc Kamionkowski1 1Department of Physics & Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA 2Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, 31 Caroline St N, Waterloo, ON N2L 2Y5, Canada (Dated: August 6, 2021) Velocity fields can be reconstructed at cosmological scales from their influence on the correlation between the cosmic microwave background and large-scale structure. Effects that induce such corre- lations include the kinetic Sunyaev Zel'dovich (kSZ) effect and the moving-lens effect, both of which will be measured to high precision with upcoming cosmology experiments. Galaxy measurements also provide a window into measuring velocities from the effect of redshift-space distortions (RSDs). The information that can be accessed from the kSZ or RSDs, however, is limited by astrophysical uncertainties and systematic effects, which may significantly reduce our ability to constrain cosmo- logical parameters such as fσ8. In this paper, we show how the large-scale transverse-velocity field, which can be reconstructed from measurements of the moving-lens effect, can be used to measure fσ8 to high precision. I. INTRODUCTION rameter, defined such that brsd = 1 in the absence of anisotropic selection effects.1 Anisotropic selection Next generation cosmic microwave background (CMB) effects could significantly degrade measurements of experiments such as the Simons Observatory (SO) [1,2] f σ8 from future galaxy surveys, due to degeneracy and CMB-S4 [3], and galaxy surveys such as DESI [4] with brsd. In this paper, we propose a complementary and the Vera Rubin Observatory (VRO) [5] will gener- method for measuring f σ8 in which all degeneracies ate a wealth of new data with unprecedented precision with astrophysical bias parameters are broken. -

Blossoms Video Module Galaxies And

BLOSSOMS VIDEO MODULE GALAXIES AND DARK MATTER BY PETER FISHER So hello! My name is Peter Fisher. I’m a professor here at MIT and this is a Blossoms module on galaxies and dark matter. In the next hour we’re going to talk about what a galaxy is and a little bit about how it works. Then we’re going to talk about how, in order to understand how a galaxy works, we need to introduce a new form of matter which is called dark matter. Dark matter is one of the most pressing issues for physicists today because we really don’t have any idea what dark matter is. We’ll talk a little bit toward the end about dark matter’s properties but really the main message is that the shape of our galaxy is really determined by the presence of dark matter. Many of you probably know that galaxies are large collections of stars but we didn’t always know that. Around the turn of the century people looked at images like this one, which shows a cluster of actually 1,000 galaxies called the Coma Cluster and they saw that in contrast to the surrounding stars, galaxies were fuzzy, they were extended, whereas stars looked like little light points, and they were different colors. Astronomers referred to them at nebulae. The word comes from the Latin for fog or mist, so they were like these little blobs of mist. And it was some time before astronomers realized, about the turn of the century as I mentioned, that galaxies were really very large collections of stars.