A Postmodern Journey Through Dance Culture. by Gareth Wynne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music Reading Read the Passage, the E-Mail and the Festival Guide. the Glastonbury Festival Is an Unforgettable Sight. for Three

Music Reading Read the passage, the e-mail and the festival guide. The Glastonbury Festival is an unforgettable sight. For three days, 280 hectares of peaceful farm country in the beautiful Somerset Valley become a vast, colourful tent city. The Glastonbury Festival is Britain's largest outdoor rock concert, and it attracts crowds of more than 100,000 people. It has six separate stages for musicians to play on. It has eighteen markets where fans can buy things. It has its own daily newspaper and is even broadcast live on television. It also raises large amounts of money for several charities, including Greenpeace and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Glastonbury is just one of many events on the international music festival calendar each year. For dance music fans, there's Creamfields, the Essential Festival and Homelands - all in the UK. Rock fans have Roskilde Festival in Denmark, Fuji Rock and Summer Sonic in Japan, and the Livid Festival and the Big Day Out in Australia. And the crowds just keep getting bigger. In fact, the size of some of these festivals is causing problems. Since the deaths of nine people at Roskiide in 2000 and the death of a young woman at the 2001 Big Day Out, festival organisers and local police have been working together to make sure festival-goers stay safe. Despite these tragic events, festivals are more popular than ever. And it's not just about the music. It's about making new friends and partying non-stop for days at a time. It's about dancing till you can't stand up anymore and then crashing in someone else's tent. -

The Psytrance Party

THE PSYTRANCE PARTY C. DE LEDESMA M.Phil. 2011 THE PSYTRANCE PARTY CHARLES DE LEDESMA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of East London for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2011 Abstract In my study, I explore a specific kind of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) event - the psytrance party to highlight the importance of social connectivity and the generation of a modern form of communitas (Turner, 1969, 1982). Since the early 90s psytrance, and a related earlier style, Goa trance, have been understood as hedonist music cultures where participants seek to get into a trance-like state through all night dancing and psychedelic drugs consumption. Authors (Cole and Hannan, 1997; D’Andrea, 2007; Partridge, 2004; St John 2010a and 2010b; Saldanha, 2007) conflate this electronic dance music with spirituality and indigene rituals. In addition, they locate psytrance in a neo-psychedelic countercultural continuum with roots stretching back to the 1960s. Others locate the trance party events, driven by fast, hypnotic, beat-driven, largely instrumental music, as post sub cultural and neo-tribal, representing symbolic resistance to capitalism and neo liberalism. My study is in partial agreement with these readings when applied to genre history, but questions their validity for contemporary practice. The data I collected at and around the 2008 Offworld festival demonstrates that participants found the psytrance experience enjoyable and enriching, despite an apparent lack of overt euphoria, spectacular transgression, or sustained hedonism. I suggest that my work adds to an existing body of literature on psytrance in its exploration of a dance music event as a liminal space, redolent with communitas, but one too which foregrounds mundane features, such as socialising and pleasure. -

Rochester Winners

ROCHESTER WINNERS TOP 5 JUNIOR PETITE INTERMEDIATE SOLOS Place Routine Title Studio Name # of Dancers 5TH NO EXCUSES Spins Dance Studio Inc. LAINEY WEIERMILLER 4TH GROOVE IS IN THE HEART Dunwoody Dance RAIVYN CRANFORD 3RD SUGAR PIE Dance Emporium KATE REHBERG 2ND RUNWAY WALK TNT Dance Explosion EMMA CLAUSEN 1ST GOOD NIGHT Elite Studio of Dance MARKO KOKOVIC TOP 3 JUNIOR PETITE COMPETITIVE SOLOS Place Routine Title Studio Name # of Dancers CORRINA 3RD CHOO CHOO CHA BOOGIE Studio East Dance Company PICCARRETO 2ND NEVER GROW UP Alaina Visalli Dance Company ELLA KIRCHOFF 1ST STRUT Alaina Visalli Dance Company ELLA KIRCHOFF TOP 5 JUNIOR INTERMEDIATE SOLO Place Routine Title Studio Name # of Dancers 5TH HOLLYWOOD Spins Dance Studio Inc. KENSINGTON PITTI 4TH WILD Anastasia’s Spotlight Dance MARLEY WRIDE 3RD HERE COMES THE SUN Elite Studio of Dance AINSLEY KLUS 2ND DIME Miss.Lisa’s Artistry of Dance GLORIANNA PHELPS 1ST BEAT GOES ON Sole Movement and Dance MALEI WIGHT TOP 10 JUNIOR COMPETITIVE SOLOS Place Routine Title Studio Name # of Dancers 10TH AYE CARUMBA Steppin’ Out Dance Academy SADIE HERBERGER 9TH TAKE OVER Alaina Visalli Dance Company JEMMA COON 8TH FLY TNT Dance Explosion ANGELINA FICO 7TH SOMETHING THAT I WANT Spins Dance Studio Inc. MIA CHARTIER 6TH SWEET GEORGIA BROWN TNT Dance Explosion ANIYAH GAMBLE 5TH LITTLE VOICE Alaina Visalli Dance Company JEMMA COON 4TH HOLLYROCK Steppin’ Out Dance Academy KAELYN GALLAGHER 3RD SIGN OF THE TIMES TNT Dance Explosion MALLORY PENNER JOCELYN 2ND OPPOSITES ATTRACT Steppin’ Out Dance Academy HUPKOWICZ -

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival DC

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF REGINA, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract !is article explores the religio-spiritual characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending speci"cally to the characteristics of what I call neotrance apparent within the contemporary trance event, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ultimate concerns” within the festival framework. An exploration of the psychedelic festival offers insights on ecstatic (self- transcendent), performative (self-expressive) and re!exive (conscious alternative) trajectories within psytrance music culture. I address this dynamic with reference to Portugal’s Boom Festival. Keywords psytrance, neotrance, psychedelic festival, trance states, religion, new spirituality, liminality, neotribe Figure 1: Main Floor, Boom Festival 2008, Portugal – Photo by jakob kolar www.jacomedia.net As electronic dance music cultures (EDMCs) flourish in the global present, their relig- ious and/or spiritual character have become common subjects of exploration for scholars of religion, music and culture.1 This article addresses the religio-spiritual Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 35-64 + Dancecult ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DC Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture – DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03 + D DC –C 36 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending specifically to the charac- teristics of the contemporary trance event which I call neotrance, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ul- timate concerns” within the framework of the “visionary” music festival. -

Neo-Tribe Sociality in a Neoliberal World: a Case Study of Shambhala Music Festival Adrienne Ratushniak St

Neo-tribe Sociality in a Neoliberal World: A Case Study of Shambhala Music Festival Adrienne Ratushniak St. Francis Xavier University , [email protected] ABSTRACT This case study of the electronic dance music (EDM) festival, Shambhala, in British Columbia, examines contemporary sociality. Both popular perception and academic discussion suggest that contemporary, neoliberal society is individualizing. In contrast, Michel Maffesoli (1996) argues that sociality is continuing but in a different form – what he refers to as a contemporary form of “neo-tribes,” temporary and episodic emotional communities formed through collective interest that counteract the alienating effect of neoliberal society. This research explores those two theories, using the 2015 Shambhala Music Festival, a single location of sociality, as the case study. The results of a rapid ethnographic study conducted throughout the festival’s duration in August 2015 indicate that most attendees enthusiastically confirm neo-tribalism, describing the festival as a powerful emotional “vibe” experienced collectively; sharing with and caring for each other; and a family-like “Shambhalove” among festival attendees; however, participant observation and close examination of the evidence also shows a few specific instances of neoliberal individualism. This paper explores how a community with strong neo-tribe characteristics can exist in a neoliberal capitalist context and with some attendees whose main reason for being at Shambhala is their own individual consumer gratification. Keywords: sociality, individualism, music festivals, neo-tribe, neoliberalism ISSN 2369-8721 | The JUE Volume 7 Issue 2, 2017 54 experience with the festival. I have attended the festival twice prior to this research, in 2013 and 2014, and my insider knowledge has given me an understanding of the festival which was useful in designing the research and proved valuable in my analysis of the data. -

Most Requested Songs of 2009

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on nearly 2 million requests made at weddings & parties through the DJ Intelligence music request system in 2009 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 5 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 6 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 7 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 8 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 9 B-52's Love Shack 10 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 11 ABBA Dancing Queen 12 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 13 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 14 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 15 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 16 Outkast Hey Ya! 17 Sister Sledge We Are Family 18 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 19 Kool & The Gang Celebration 20 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 21 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 22 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 23 Lady Gaga Poker Face 24 Beatles Twist And Shout 25 James, Etta At Last 26 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 27 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 28 Jackson, Michael Thriller 29 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 30 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 31 Commodores Brick House 32 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 33 Temptations My Girl 34 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 35 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 36 Bee Gees Stayin' Alive 37 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 38 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

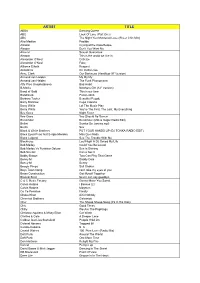

APRIL 22 ISSUE Orders Due March 24 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH Axis.Wmg.Com 4/22/17 RSD AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP

2017 NEW RELEASE SPECIAL APRIL 22 ISSUE Orders Due March 24 MUSIC • FILM • MERCH axis.wmg.com 4/22/17 RSD AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Le Soleil Est Pres de Moi (12" Single Air Splatter Vinyl)(Record Store Day PRH A 190295857370 559589 14.98 3/24/17 Exclusive) Anni-Frid Frida (Vinyl)(Record Store Day Exclusive) PRL A 190295838744 60247-P 21.98 3/24/17 Wild Season (feat. Florence Banks & Steelz Welch)(Explicit)(Vinyl Single)(Record WB S 054391960221 558713 7.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Cracked Actor (Live Los Angeles, Bowie, David PRH A 190295869373 559537 39.98 3/24/17 '74)(3LP)(Record Store Day Exclusive) BOWPROMO (GEM Promo LP)(1LP Vinyl Bowie, David PRH A 190295875329 559540 54.98 3/24/17 Box)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Live at the Agora, 1978. (2LP)(Record Cars, The ECG A 081227940867 559102 29.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Live from Los Angeles (Vinyl)(Record Clark, Brandy WB A 093624913894 558896 14.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Greatest Hits Acoustic (2LP Picture Cure, The ECG A 081227940812 559251 31.98 3/24/17 Disc)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Greatest Hits (2LP Picture Disc)(Record Cure, The ECG A 081227940805 559252 31.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Groove Is In The Heart / What Is Love? Deee-Lite ECG A 081227940980 66622 14.98 3/24/17 (Pink Vinyl)(Record Store Day Exclusive) Coral Fang (Explicit)(Red Vinyl)(Record Distillers, The RRW A 081227941468 48420 21.98 3/24/17 Store Day Exclusive) Live At The Matrix '67 (Vinyl)(Record Doors, The ECG A 081227940881 559094 21.98 3/24/17 -

The Electronic Music Scene's Spatial Milieu

The electronic music scene’s spatial milieu How space and place influence the formation of electronic music scenes – a comparison of the electronic music industries of Berlin and Amsterdam Research Master Urban Studies Hade Dorst – 5921791 [email protected] Supervisor: prof. Robert Kloosterman Abstract Music industries draw on the identity of their locations, and thrive under certain spatial conditions – or so it is hypothesized in this article. An overview is presented of the spatial conditions most beneficial for a flourishing electronic music industry, followed by a qualitative exploration of the development of two of the industry’s epicentres, Berlin and Amsterdam. It is shown that factors such as affordable spaces for music production, the existence of distinctive locations, affordability of living costs, and the density and type of actors in the scene have a significant impact on the structure of the electronic music scene. In Berlin, due to an abundance of vacant spaces and a lack of (enforcement of) regulation after the fall of the wall, a world-renowned club scene has emerged. A stricter enforcement of regulation and a shortage of inner-city space for creative activity in Amsterdam have resulted in a music scene where festivals and promoters predominate. Keywords economic geography, electronic music industry, music scenes, Berlin, Amsterdam Introduction The origins of many music genres can be related back to particular places, and in turn several cities are known to foster clusters of certain strands of the music industry (Lovering, 1998; Johansson and Bell, 2012). This also holds for electronic music; although the origins of techno and house can be traced back to Detroit and Chicago respectively, these genres matured in Germany and the Netherlands, especially in their capitals Berlin and Amsterdam. -

James T Playlist

ARTIST TITLE ABBA Dancing Queen ABC Look Of Love (Part One) ABC The Night You Murdered Love (Sheer Chic Mix) Afro Medisa Pasilda Alcazar Crying at the discotheque Alcazar Don't You Want Me Alcazar Sexual Guarantee Alcazar This is the world we live in Alexander O'Neal Criticize Alexander O'Neal Fake Alliance Ethnik Respect Anastacia I'm Outta Love Anne Clark Our Darkness (Hardfloor 97 Version) Armand van Helden My My My Armand van Helden The Funk Phenomena Atfc Pres Onephatdeeva Bad Habit B-Movie Nowhere Girl (12'' Version) Band of Gold This is our time Bandolero Paris Latino Barbara Tucker Beautiful People Barry Manilow Copa Cabana Barry White Let The Music Play Barry White You're The First, The Last, My Everything Bee Gees Night Fever Bee Gees You Should Be Dancin Bel Amour Bel Amour (Milk & Sugar Radio Edit) Bellini Samba De Janeiro.mp3 Berlin Sex Black & White Brothers PUT YOUR HANDS UP (DJ TONKA RADIO EDIT) Black Eyed Peas feat Sergio Mendes Mas Que Nada Black Legend See The Trouble With Me Blacknuss Last Night A DJ Saved My Life Bob Marley Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Vs Funkstar Deluxe Sun Is Shining Bob Sinclair Can u feel it Bobby Brown Two Can Play That Game Boney M Daddy Cool Boney M Sunny Boogie Pimps Salt Shaker Boys Town Gang can't take my eyes of you Brass Construction Got Myself Together Bronski Beat Never can say goodbye C & C Music Factory Gonna Make You Sweat Calvin Rotane I Believe (2) Calvin Rotane Magnum Ce Ce Peniston Finally Chaka Khan Ain't Nobody Chemical Brothers Galvanize Cher The Shoop Shoop Song (It's In His Kiss) Chic Good Times Chilly We Are The PopKings Christina Aguilera & Missy Elliot Car Wash Clivilles & Cole A Deeper Love Coldcut feat Lisa Stansfield People Hold On Colonel Abrams Trapped 98 Combo Cubano S C Crystal Waters 100 Pure Love (Radio Mix) Daft Punk Around The World Daft Punk One More Time Dan Hartman Relight My Fire Danzel Pump it up David Bowie & Mick Jagger Dancing In The Street DB Boulevard Point Of View Deee Lite Groove Is In The Heart ARTIST TITLE Delegation Heartache No. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #8: Music Boo-Hooray Catalog #8

Boo-Hooray Catalog #8: Music Boo-Hooray Catalog #8 Music Boo-Hooray is proud to present our eighth antiquarian catalog, dedicated to music artifacts and ephemera. Included in the catalog is unique artwork by Tomata Du Plenty of The Screamers, several incredible items documenting music fan culture including handmade sleeves for jazz 45s, and rare paste-ups from reggae’s entrance into North America. Readers will also find the handmade press kit for the early Björk band, KUKL, several incredible hip-hop posters, and much more. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Ben Papaleo, Evan, and Daylon. Layout by Evan. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Table of Contents 31. [Patti Smith] Hey Joe (Version) b/w Piss Factory .................. -

Interpretive Redesign Through Music Dialogue in Classroom Practices

australian societa y fo r s music educationm e Transformative music invention: i ncorporated interpretive redesign through music dialogue in classroom practices Michelle Tomlinson Griffith University Abstract In this thematic case study in a rural primary school, young children of diverse socio-cultural origins use transformative and transmodal redesign in music as they explore new conceptual meanings through self-reflexive interaction in classroom music events. A focus on music dialogue created by interaction between modes is seen to promote inclusiveness and transformation of learning. This praxial approach to music learning in the classroom context uncovers hidden dogma used to justify existing structures in the curriculum. In music education in Australia there is still a common failure to acknowledge that embodied and situated music making found in “everyday life” (De Nora, 2011) is linked to conceptual knowledge of music. In this study, investigating young children’s selections of semiotic resources when redesigning meaning in a dialogue of modes enables educators to determine how conceptual knowledge of music is established, extended and expanded through children’s developing understanding of the elements of music during redesign. The complexity of young children’s use of music imagery and genre and their grasp of music concepts is evident in their interactions in classroom music events. Awareness of the space of music dialogue allows for a deeper insight in children’s capacity for music invention. Key words: classroom music dialogue, semiotic redesign, praxis, multimodality, music invention. Australian Journal of Music Education 2012:1, 42-56 Introduction not always used in conjunction, but rather are selected by children in specific combinations for The unique nature of music in the curriculum can particular uses in situated classroom practice.