Wayne Krantz' Guitar Playing from a Practice-Based Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Keith Carlock

APRIZEPACKAGEFROM 2%!3/.34/,/6%"),,"25&/2$s.%/.42%%3 7). 3ABIANWORTHOVER -ARCH 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE 'ET'OOD 4(%$25--%23/& !,)#)!+%93 $!.'%2-/53% #/(%%$ 0,!.4+2!533 /.345$)/3/5.$3 34!249/52/7. 4%!#().'02!#4)#% 3TEELY$AN7AYNE+RANTZS ,&*5)$"3-0$,7(9(%34(%-!.4/7!4#( s,/52%%$34/.9h4(5.$%2v3-)4( s*!+),)%"%:%)4/&#!. s$/5",%"!3335"34)454% 2%6)%7%$ -/$%2.$25--%2#/- '2%43#(052%7//$"%%#(3/5,4/.%/,$3#(//,3*/9&5,./)3%%,)4%3.!2%3%6!.34/-0/7%2#%.4%23 Volume 35, Number 3 • Cover photo by Rick Malkin CONTENTS 48 31 GET GOOD: STUDIO SOUNDS Four of today’s most skilled recording drummers, whose tones Rick Malkin have graced the work of Gnarls Barkley, Alicia Keys, Robert Plant & Alison Krauss, and Coheed And Cambria, among many others, share their thoughts on getting what you’re after. 40 TONY “THUNDER” SMITH Lou Reed’s sensitive powerhouse traveled a long and twisting musical path to his current destination. He might not have realized it at the time, but the lessons and skills he learned along the way prepared him per- fectly for Reed’s relentlessly exploratory rock ’n’ roll. 48 KEITH CARLOCK The drummer behind platinum-selling records and SRO tours reveals his secrets on his first-ever DVD, The Big Picture: Phrasing, Improvisation, Style & Technique. Modern Drummer gets the inside scoop. 31 40 12 UPDATE 7 Walkers’ BILL KREUTZMANN EJ DeCoske STEWART COPELAND’s World Percussion Concerto Neon Trees’ ELAINE BRADLEY 16 GIMME 10! Hot Hot Heat’s PAUL HAWLEY 82 PORTRAITS The Black Keys’ PATRICK CARNEY 84 9 REASONS TO LOVE Paul La Raia BILL BRUFORD 82 84 96 -

KRANTZ/CARLOCK/LEFEBVRE – Live in Mainz Mi

KCL – Live in Mainz! Seite 1 von 5 KRANTZ/CARLOCK/LEFEBVRE – Live in Mainz Mi. 26. Februar 2020, 20:30 im M8, Mainz, Mitternacht 8 www.jazz-mainz.de Wayne Krantz – guitar Keith Carlock – drums Tim Lefebvre – bass www.waynekrantz.com KCL – Live in Mainz! Seite 2 von 5 WAYNE KRANTZ - guitar Krantz arbeitete bei Bands und Musikern wie Steely Dan, Michael Brecker, Billy Cobham und anderen. Seit Anfang der 1990er Jahre nahm er unter eigenem Namen eine Reihe von Alben auf, beginnend mit Signals, das er Mitte 1990 mit Jim Beard, Leni Stern, Hiram Bullock, Anthony Jackson, Dennis Chambers und Don Alias für Enja einspielte. Die ersten weiteren Alben hat er im Trio mit dem Bassisten Lincoln Goines und dem Schlagzeuger Zach Danzinger aufgenommen, Greenwich Mean und Your Basic Live mit Tim Lefebvre und Keith Carlock. Er hat mehrere Tourneen durch Europa und Asien hinter sich, ist aber meist donnerstags abends in der New Yorker 55 Bar anzutreffen. In letzter Zeit war Wayne Krantz auf Tour und im Studio mit Chris Potter und bei den Aufnahmesessions für das Album Morph the Cat des Keyboarders und Sängers Donald Fagen beteiligt. Seit 2013 spielt Krantz mit Michael Landau und Jimmy Herring in der Band The Ringers. Stil, Sound und Equipment Die Musik von Wayne Krantz ist beeinflusst von Jazz und Rock. Er hat einen ganz eigenen Stil entwickelt, bei dem vor allem seine sehr rhythmische Spielweise und die häufige Nutzung von leeren Saiten auffällt. Krantz legt großen Wert auf improvisatorische Freiheit und musikalische Gruppendynamik. Er setzt oft einen Moogerfooger Ringmodulator ein, der seine rhythmische Spielweise noch mehr zur Geltung bringt. -

An Analysis of Nate Wood's Drumming on The

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2018 Neoteric Drum Set Orchestration: An analysis of Nate Wood’s drumming on the music of Tigran Hamasyan Ryan George Daunt Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Daunt, R. G. (2018). Neoteric Drum Set Orchestration: An analysis of Nate Wood’s drumming on the music of Tigran Hamasyan. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1519 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1519 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Exploring and Reapplying Wayne Krantz's Method of Constructing The

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2021 Exploring and reapplying Wayne Krantz’s method of constructing the album Greenwich Mean Christian A. Meares Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Composition Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Meares, C. A. G. (2021). Exploring and reapplying Wayne Krantz’s method of constructing the album Greenwich Mean.https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1568 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1568 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Too Funky 2 Ignore Demonstrates Just How Accomplished He Has Become at the Craft

HHIIRRAAMM BBUULLLLOOCCKK TOO FFUUNNKKYY 22 IGNORE BHM 1010-2 Over the course of his career -- from his mid ‘70s run with The Brecker Brothers to his various stints as a“hired gun” for everyone from Gil Evans, Carla Bley and David Sanborn to Michael Franks and Miles Davis -- Hiram Bullock earned his reputation as a bona fide guitar hero. But all along, Bullock has also been developing his skills as a songwriter. Too Funky 2 Ignore demonstrates just how accomplished he has become at the craft. “I think I’ve gotten better at it as I’ve been doing it,” says the charismatic Guitar Man. While the funk quotient on Bullock’s 12th recording as a leader is off the charts and the album is chockfull of blistering, Hendrixian guitar licks, Too Funky 2 Ignore also showcases Hiram’s adeptness at meticulously layering track upon track in the studio in a Steely Dan-ish vein. “I have actually consciously focused on that craft,” says the guitarist-producer. “And part of what allowed me to do that was getting a studio of my own. The technology has increased to the point where now a regular person can have a studio at home. And because of that, I can cut a track and then sit with it for months if I need to -- rework a lyric or work on backing vocals and rhythm guitar parts. So it’s not like it used to be where you go into the studio and sing all the lead vocal stuff in one day and what you get on that day is what you have on the record. -

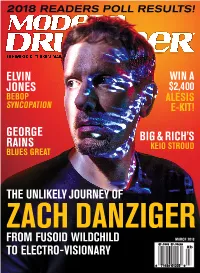

38 ZACH DANZIGER He Freely Breaks Every Rule 26 on TOPIC: PATTY SCHEMEL but One: to Thine Own Self by Stephen Bidwell Be True

2018 READERS POLL RESULTS! THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE ELVIN WIN A JONES $2,400 BEBOP ALESIS SYNCOPATION E-KIT! GEORGE BIG & RICH’S RAINS KEIO STROUD BLUES GREAT THE UNLIKELY JOURNEY OF ZACH DANZIGER FROM FUSOID WILDCHILD MARCH 2018 TO ELECTRO-VISIONARY 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 83% OF DRUMMERS SAID THEY’D SWITCH TO UV1. OMAR HAKIM ACTUALLY DID.* * MAYBE THAT’S BECAUSE THE NEW EVANS UV1 10mil single-ply drumhead is more versatile and durable than the heads they were playing before, thanks to its patented UV-cured coating. UV1.EVANSDRUMHEADS.COM Congratulations are in order for our Audix endorsers who were recognized by the readers of Modern Drummer this year! Our artist endorsers are a part of the Audix family. We are proud of the contributions they provide through volunteering their time to educate, support, and serve as leaders for the drumming community. TODD SUCHERMAN THOMAS LANG STANTON MOORE Progressive & Recorded Clinician / Educator Clinician / Educator & Performance Educational Product D2D4 D6 ADX51 i5 ©2017 Audix Corporation All Rights Reserved. Audix and audixusa.com all the Audix logos are trademarks of Audix Corporation. 503.682.6933 The Chosen Ones Choose Yamaha It is our privilege to recognize this year’s Readers Poll nominees for excellence in artistry, and we are honored that these outstanding performers choose to play Yamaha. Congratulations from all of us to all of you. CONTENTS Volume 42 • Number 3 CONTENTS Cover and Contents photos by Lloyd Bishop ON THE COVER 38 ZACH DANZIGER He freely breaks every rule 26 ON TOPIC: PATTY SCHEMEL but one: To thine own self by Stephen Bidwell be true. -

Inside the Jazzomat

Martin Pfleiderer, Klaus Frieler, Jakob Abeßer, Wolf-Georg Zaddach, Benjamin Burkhart (Eds.) Inside the Jazzomat New Perspectives for Jazz Research Veröffentlicht unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 The book was funded by the German Research Foundation (research project „Melodisch-rhythmische Gestaltung von Jazzimprovisationen. Rechnerbasierte Musikanalyse einstimmiger Jazzsoli“) 978-3-95983-124-6 (Paperback) 978-3-95983-125-3 (Hardcover) © 2017 Schott Music GmbH & Co. KG, Mainz www.schott-campus.com Cover: Portrait of Fats Navarro, Charlie Rouse, Ernie Henry and Tadd Dameron, New York, N.Y., between 1946 and 1948 (detail) © William P. Gottlieb (Library of Congress) Veröffentlicht unter der Creative-Commons-Lizenz CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Martin Pfleiderer, Klaus Frieler, Jakob Abeßer, Wolf-Georg Zaddach, Benjamin Burkhart (Eds.) Inside the Jazzomat New Perspectives for Jazz Research Contents Acknowledgements 1 Intro Introduction 5 Martin Pfleiderer Head: Data and concepts The Weimar Jazz Database 19 Martin Pfleiderer Computational melody analysis 41 Klaus Frieler Statistical feature selection: searching for musical style 85 Martin Pfleiderer, Jakob Abeßer Score-informed audio analysis of jazz improvisation 97 Jakob Abeßer, Klaus Frieler Solos: Case studies Don Byas’s “Body and Soul” 133 Martin Pfleiderer Mellow Miles? On the dramaturgy of Miles Davis’s “Airegin” 151 Benjamin Burkhart ii West Coast lyricists: Paul Desmond and Chet Baker 175 Benjamin Burkhart Trumpet giants: Freddie Hubbard and Woody Shaw 197 Benjamin Burkhart Michael Brecker’s -

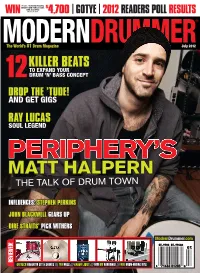

Matt Halpern

02):%3&2/-$7 0!#)&)# $25-3!.$0%2#533)/. !.$:),$*)!. 8*/ 6!,5%$!4/6%2 (05:& 3&"%&3410--3&46-54 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE *ULY ,*--&3#&"54 4/%80!.$9/52 $25-."!33#/.#%04 %3015)&56%& !.$'%4')'3 3":-6$"4 3/5,,%'%.$ * ,* ,9½- //Ê* , / Ê/Ê"Ê ,1Ê/"7 */'-6&/$&445&1)&/1&3,*/4 +0)/#-"$,8&--(&"3461 %*3&453"*541*$,8*5)&34 -ODERN$RUMMERCOM 3&7*&8&% (3&54$)#300,-:/4&54/"3&4539/3(4(3007&+6*$&/&8%8)"3%8"3&.9-%36..*,*/(,*54 Volume 36, Number 7 • Cover photo by Sahisnu Sadarpo CONTENTS MODERN DRUMMER Ash Newell 2012 Sahisnu Sadarpo READERSWinners POLL 18 2012 READERS POLL RESULTS There’s so much drumming talent today, across so many different styles, that it’s a miracle MD readers are able to choose favorites. But choose you did, and once again we’re excited and honored to share those picks. 48 MATT HALPERN by Ken Micallef Paul La Raia The exceptionally diverse, super-polished pounder is at the forefront of a scene that shows little interest in what can’t be done on the drumset. 58 RAY LUCAS by Jim Payne 12 UPDATE He jammed regularly with Hendrix, shared stages with Ringo at • The Meters’ ZIGABOO MODELISTE the height of Beatlemania, and set a standard that some of the world’s greatest players aspired to. • Pop-Star Drummer GOTYE • The Mars Volta’s DEANTONI PARKS Brian Nevins 36 WOODSHED MIKE JOHNSTON of MikesLessons.com 42 PORTRAITS Red Fang’s JOHN SHERMAN Alex Solca 44 FIRST PERSON PARENTING PERSPECTIVES Appreciating the Sacrifices of My Father by David Ciauro 84 WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT...? Dire Straits’ PICK WITHERS 64 INFLUENCES: ENTER TO WIN ONE OF THREE INCREDIBLE PRIZES FROM DW, PACIFIC STEPHEN PERKINS DRUMS AND PERCUSSION, AND ZILDJIAN! by Stephen Bidwell Contest Whether he’s playing just a shaker and a pair of bongos valued $ or bashing home the finale of one of Jane’s Addiction’s at over more heady epics, his drive and feel are inspirational. -

Catalog Enja No Titel Bar Code Blues Beacon BLU-1007 2

Catalog Enja No Titel Artist bar code Blues Beacon Blues Music Catalog BLU-1007 2 BOOGIE WOOGIE & SOME BLUES Willisohn, Christian solo piano 036757100720 BLU-1013 2 BIG HEART Woodland ,Nick British blues-rock 063757101321 BLU-1016 2 I'M TROUBLE Jackson,Yvonne w. Maceo Parker 063757101628 BLU-1017 2 THE GOSPEL BOOK Boutté, Lillian The queen of New Orleans 063757101727 BLU-1019 2 BLUES NEWS Willisohn / Van der Leek 063757101925 BLU-1020 2 THE JAZZ BOOK Boutte, Lillian 063757102021 BLU-1024 2 WATCH THIS! Jones, Al 063757102427 BLU-1025 2 BLUES ON THE WORLD Willisohn, Christian 063757102526 BLU-1026 2 HEART BROKEN MAN Willisohn, Christian 063757102629 BLU-1027 2 LIVE FIREWORKS Woodland; Nick 063757102724 BLU-1030 2 TRIED AND TRUE Hall, Marty 063757103028 BLU-1031 2 BATUQUE Y BLUES Big Allenbik Brazilian Blues Band 063757103127 BLU-1033 2 WHO'S BEEN TALKIN'? Hall ,Marty 063757103325 BLU-1034 2 SHARPER THAN A TACK Jones, Al 063657103427 BLU-1036 2 THE CURRENT THAT FLOWS Woodland, Nick 063757103622 BLU-1037 2 CULT FACTORY, Vol. I Woodland, Nick 063757103721 BLU-1038 2 GOOD BURN CLEARING HOUSE Woodland, Nick 063757103820 enja (24bit master edition) Jazz and World Music Catalog ENJ-2101 2 SEQUOIA SONG Degen, Bob 063757210122 ENJ-2102 2 NOW HEAR THIS Galper, Hal - Hino, T.. 063757210221 ENJ-2104 2 TARO'S MOOD Hino, Terumasa 2-CD 063757210429 ENJ-2105 2 OUTLAWS Steig, J. - Gomez, E. 063757210528 ENJ-2106 2 IVORY FOREST Galper,Hal - Scofield,J. 063757210627 ENJ-2107 2 FATHER TIME Tusa, F. - Liebman,D. 063757210726 ENJ-2108 2 MYSTIC BRIDGE Wallace, -

XRIJF – 13 Years Lineup – 2002-2014

XRIJF – 13 Years Lineup – 2002-2014 Headliners: Aretha Franklin Chris Botti Dr. John Norah Jones Band The Average White Band The Blue Brothers Band The Rippingtons Remaining Lineup: Abraham Burton's "Forbidden Fruit" Ada Rovatti's "Elephunk" Akira Tana's Japanese All Star Quartet Beatle Jazz John Hammond (solo) Brad Mehldau Trio Brian Kellock Carnegie Hall Jazz Band Charles Mingus selected film shorts Dan Hicks & The Hot Licks David Murray -- "Jazzman " Dewey Time -- The Story of Dewey Redman Diane Reeves Duke Ellington European Jazz Ensemble European Jazz Ensemble Gap Mangione Big Band Greg Osby/Jason Moran Duo Helio Alves' Brazilian Love Affair rochesterjazz.com XRIJF – 13 Years Lineup – 2002-2014 It's Time for "T -- The Legend of Jack Teagarden Jane Bunnett & Spirits of Havana Jane Bunnett & Spirits of Havana Jazz MaTazz with Hayes Greenfield (jazz for kids) Jazz Shorts Animation & Performances Jimmy Wolf Joe Lovano's "Trio Fascination " Joe Romano Quartet John Abercrombie Trio John Mooney Band Jon Ballantyne Little Feat Matt Wilson Quartet (jazz for kids) Medeski Martin and Wood Metalwood Pacquito D'Rivera's UN Ensemble and Akira Tana's Japanese All Star Quartet Paul Bollenback & Joe Locke Quartet featuring Jeff 'Tain' Watts and James Genus Prime Time Funk Randy Brecker's Randroid Band Renee Rosnes Cabo Frio Respect Quartet RIT Alumni Chorale and The Dave Rivello Big Band / Films celebrating: Louis Armstrong -- 30 Years of TV Performances; "Bird" Round Midnight starring Dexter Gordon Russell Gunn w/ Gray Mayfield Trio Sonny Rollins -

Berklee College of Music Video Services Event Recordings, 1979-2005 BCA-018 Finding Aid Prepared by Amanda Axel; with Sofía Becerra-Licha

Berklee College of Music Video Services Event Recordings, 1979-2005 BCA-018 Finding aid prepared by Amanda Axel; with Sofía Becerra-Licha This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit December 07, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Third edition Berklee Archives 2014/07/30 Berklee College of Music 1140 Boylston St Boston, MA, 02215 617-747-8001 Berklee College of Music Video Services Event Recordings, 1979-2005 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical/Historical note.......................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note............................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement note...........................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................5 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................6 Collection Inventory.....................................................................................................................................