Bill Lester-Dockery Farm Interview]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understand the Past, See the Future, & Make an Impact

Mississippi Delta 2012 Mississippi State University Understand the past, see the future, & make an impact... TABLE OF CONTENTS Emergency Contacts & Rules and Reminders............................................................ 1 List of Groups - Breakfast/Clean Up Teams & Service Teams.................................. 2 Alternative Spring Break Map....................................................................................3 Sunday Itinerary.......................................................................................................... 4 North Greenwood Baptist Church...............................................................................5 Mississippians Engaged in Greener Agriculture (MEGA)......................................... 6 LEAD Center - Sunflower County Freedom Project.................................................. 7 The Help......................................................................................................................8 Monday Itinerary.........................................................................................................9 Dr. Luther Brown - Delta Heritage Tour.....................................................................10 Chinese Mission School..............................................................................................11 Dockery Farms.............................................................................................................12 Fannie Lou Hamer.......................................................................................................14 -

Dockery Farms and the Birth of the Blues

Dockery Farms and the Birth of the Blues Dockery Farms began as a cotton plantation in the Mississippi Delta. Although cotton was king in the post-Civil War South, it has been the music from the fields and cabins of Dockery Farms that make it famous as a birthplace of the blues. From its beginnings in the late 19th century through the rise of such unforgettable Delta bluesmen as Charley Patton, Robert Johnson, Son House, and Howlin' Wolf, to the many legendary blues musicians today, Dockery Farms has provided fertile ground for the blues. The vivid poetry, powerful songs, and intense performing styles of the blues have touched people of all ages around the world. The music that was created, at least in part, by Dockery farm workers a century ago continues to influence popular culture to this day. It was a welcome diversion from their hard lives and a form of personal expression that spoke of woes and joys alike in a musical language all its own. Will Dockery, the son of a Confederate general that died at the battle of Bull Run, founded the plantation. Young Will Dockery had graduated from the University of Mississippi and in 1885, with a gift of $1,000 from his grandmother, purchased forest and swampland in the Mississippi Delta near the Yazoo and Sunflower Rivers. Recognizing the richness of the soil, he cleared the woods and drained the swamps opening the land for cotton. Word went out for workers and before long African-American families began to flock to Dockery Farms in search of work in the fields and, as tenant farmers (sharecroppers,) they cultivated cotton on the rich farmland. -

Reengaging Blues Narratives: Alan Lomax, Jelly Roll Morton and W.C. Handy ©

REENGAGING BLUES NARRATIVES: ALAN LOMAX, JELLY ROLL MORTON AND W.C. HANDY By Vic Hobson A dissertation submitted to the School of Music, In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of East Anglia (March 2008) Copyright 2008 All rights reserved © This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author’s prior, written consent. i Acknowledgments This for me has been a voyage of discovery and I count myself fortunate to have enjoyed the process. This has been due, in no small part, to the support, help and encouragement that I have received along the way. People who, in the early days of my research, had been only names on the covers of books are now real; all have been helpful, most have been enthusiastic and some I now count as friends. The School of Music at the University of East Anglia is a small school in a rapidly expanding university which was led for many years by David Chadd who sadly died before the completion of this work. Fortunately the foundations he laid are secure and I have benefited from the knowledge and experience of all of the staff of the school, in particular my supervisor Jonathan Impett. Among Jonathan’s contributions, above and beyond the normal duties of a PhD supervisor is to have shown faith in a thesis that initially must have seemed rather unlikely. -

NEH July 2016 Daniel Warner Rich Soil, Poor People- a Week in The

Rich Soil, Poor People: A Week in the Mississippi Delta by Daniel Warner The Mississippi Delta has a certain agreeability to it. The people are humble here, acquainted with patterns of patience as seasons of planting and harvest and the give and take of drought and flood continue to shape their lives. Maybe they are humble because they know they are dependent. They depend on the land, the river, the harvest, the planter, the Lord. Like many charming places and charming people, you get a sense that you understand the Delta before you do. It invites you in, but it does not rush to show its cards. The quest for empire and glory in the heart of its historic characters is reminiscent of a Steinbeck novel. The sheer flatness of the land, though, pauses the parallel to life in the desert valleys of central California. Cotton in the fields of the Delta did not shine with the same opportunity for a new life as gold did in rivers of the West. There has always been an arrangement of things here, a set social order, a clear understanding as to whose the opportunity was. In the late 19th century, the Delta was still uncharted wilderness at the heart of a country already explored—swamp and jungle in the early era of iron horses and skyscrapers. Roaming panthers and bears haunted the cypress trees. The fear these beasts inspired can still be heard in the melodies of the oldest surviving Delta blues players. The Delta ceded this ancient landscape as it was reimagined by planters as a crescent of unprecedented fertility, stretching from Memphis to Vicksburg. -

June-2012-Portfoliocompressed.Pdf

The Most Southern Place on Earth: Music, Culture, and History in the Mississippi Delta Sponsored By: The National Endowment for the Humanities Presented By: The Delta Center for Culture and Learning at Delta State University Director: Dr. Luther Brown Coordinator for Student & Community Outreach: Lee Aylward Faculty: Mark Bonta, Henry Outlaw, Reggie Barnes, John Strait, Charles Wilson, Charles McLaurin, Scott Baretta Portfolio Created By: Minhazul Islam Robertson Scholar Duke University, Class of 2015 For More Information: Please visit the Delta Center website: www.blueshighway.org Or e-mail Dr. Luther Brown: [email protected] Delta Center for Culture & Learning Dr. Luther Brown (Director) [email protected], 662-846-4310 Welcome from the Director Dear Colleagues The Mississippi Delta is simultaneously a unique place and a place that has influenced the American story like no other. This paradox is summed up in two simple statements. Historian James Cobb has described the Delta as "The most Southern place on earth." At the same time, the National Park Service has said "Much of what is profoundly American- what people Dr. Luther Brown (Director) love about America- has come from Delta Center for Culture and Learning the delta, which is often called 'the Delta State University cradle of American culture.'" This is the Mississippi Delta: a place A place that has produced powerful political of paradox and contrast, a place leaders, both for and against segregation. A described by Will Campbell as being place in which apartheid has been replaced "of mean poverty and garish by empowerment. A place of unquestioned opulence." A place that has artistic creativity that has given the world produced great authors yet both the Blues and rock 'n' roll, and is also continues to suffer from illiteracy. -

A Social History of the Electric Guitar

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-2-2019 Why Does It Have To Be So Loud? A Social History Of The Electric Guitar Thomas Dunne CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/429 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 Why Does It Have To Be So Loud? A Social History Of The Electric Guitar by Thomas Dunne Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2019 Thesis Sponsor: May 2, 2019 Jonathan Rosenberg Date Signature May 2, 2019 Kevin Sachs Date Signature of Second Reader 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 3 2. Chapter 1 The Instrument 8 3. Chapter 2 Social Impact 34 4. Chapter 3 Guitar Gods 65 5. Conclusion 98 3 In the summer of 2017, I taught a Project-Based Learning course on the blues and the electric guitar at the Harlem Children’s Zone in New York City. The course curriculum included learning about the electric guitar, the blues, and rock ‘n’ roll. I had the kids write blues songs, and showed them my Gibson Les Paul electric guitar and let them play it. We also learned about some of the most celebrated guitarists who played this type of music, of which the children had little to no knowledge. -

Black Masculinity, Racial and Intimate Violence, and the Blues in the Mississippi Delta, 1918-1945

1 “These hard times gon’ kill you”: Black masculinity, racial and intimate violence, and the blues in the Mississippi Delta, 1918-1945 by Alexa Dagan Supervised by Dr. Jason Colby A graduating Essay Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements, in the Honours Programme. For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In the Department Of History The University of Victoria April, 2018 2 Introduction In the state of Mississippi between the years of 1882 and 1968, the NAACP estimates that 581 African-Americans were lynched, making Mississippi the lynch capital of all the southern states.1 Between 1877 and 1950, approximately 12 people were lynched in Sunflower County, which despite this statistic, is a county legendary for its music above all else.2 Between the towns of Cleveland and Ruleville is Dockery, Mississippi, home of the famous Dockery Plantation. The plantation earned its fame through the number of blues musicians who found their beginnings there, the most famous being Charley Patton. It is no coincidence that the state with the highest number of lynchings is also the one most renowned for its blues, nor that both blues musicians and lynching victims were overwhelming black, male, and working class. While the fear of lynching played a significant role in the daily lives of black men, music served an equally strong role as an opposition to this fear. Music became a form of release from the pain and violence of oppression. No matter its form, music was prevalent in all walks of life, from work songs sung by labourers and chain gangs, to holy church music, and finally to the melancholy of the blues. -

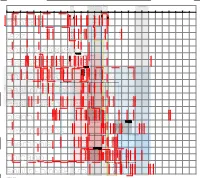

Blues Histogram

country blues john lomax born (1867) 1870 new orleans memphis chicago soul/r+b/rock+ro piano classic blues east texas blues east texas east coastblues delta blues spirituals/gospel context jazz © CUBEdesign+research illinios central rail expands south from chicago to new orleans thomas edison invents the phonograph 1880 charlie patton born mamie smith born will dockery moves to cleveland, alberta hunter born ms and opens up sawmill ma rainey born blind lemon jefferson born leadbelly born 1890 barrelhouse wc handy hears st. louis blues; + boogie considered earliest example boll weevil moves from mexico into of "jump-up" blues US destroying cotton fields big bill broonzy born sears/roebuck catalog service; affordable instruments accessible bessie smith born hc speir born tommy johnson born ida cox born national gramophone company blind boy fuller born patton family moves to dockery henry sloan heard playing blues introduces phonograph recording farms; memphis minnie born making him one of the first blues musicians anywhere mamie smith performs with dance jazz is a loose regionally collective 1900 c. patton studies under h. sloan company music-unknown outside the south blind willie mctell born son house born; louis armstrong born blind willie johnson born skip james born wc handy hears country blues charles peabody publishes "jump- while waiting for train up" blues that he hears in 1901 pete johnson born tampa red born ma rainey first appears onstage count basie born in minstrel performance meade lux lewis born roosevelt sykes born; little -

Two Steps from the Blues: Creating Discourse and Constructing Canons in Blues Criticism

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2001 Two steps from the blues: Creating discourse and constructing canons in blues criticism John M. Dougan College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Dougan, John M., "Two steps from the blues: Creating discourse and constructing canons in blues criticism" (2001). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623381. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nqf0-d245 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission. without permission. TWO STEPS FROM THE BLUES: CREATING DISCOURSE AND CONSTRUCTING CANONS IN BLUES CRITICISM A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William & Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by John M. Dougan 2001 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3026404 Copyright 2001 by Dougan, John M. All rights reserved. UMI___ ® UMI Microform 3026404 Copyright 2001 by Bell & Howell Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. -

Dockery Farms Foundation Announces Unique Music Event

Dockery Farms Foundation 255 Mississippi 8, Cleveland, MS 38732 662-719-1048 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Bill Lester, executive director [email protected] (662) 719-1048 Will Porteous, co-chair, Dockery Farms Foundation [email protected] Dockery Farms Foundation Announces Unique Music Event DOCKERY, Mississippi (April 23, 2015) - The directors of the Dockery Farms Foundation have announced a one-of-a-kind event that will bring together Rosanne Cash and several Mississippi blues artists on June 6, 2015. Set to take place on the same historic grounds where blues legends Charley Patton, Robert Johnson, Howlin’ Wolf, Tommy Johnson and Pops Staples once played, this performance will be like coming back to the source, according to Cash. She and her husband John Levanthal took several trips through the Mississippi and Arkansas Delta in recent years, and she credits that journey with inspiring the songs on her latest album The River & The Thread. The former cotton storage shed on the property will become the stage as she soaks up even more blues history and shares experiences from those trips with the audience. Will Porteous, co-chair of the Dockery Farms Foundation, said, “To have someone with Rosanne’s talent, and also a deep passion for the region, come here to perform is a dream come true. The fact that she won GRAMMY® Awards for all three of her nominations earlier this year makes this an unbelievably exciting time for us and for the whole community.” Cash won both Best American Roots Performance and Best American Roots Song for “A Feather’s Not A Bird” and Best -more- Page 2 Americana Album for The River & The Thread. -

Got a Mind to Ramble: the Story of the Blues from Clarksdale to Chicago

GOT A MIND TO RAMBLE: THE STORY OF THE BLUES FROM CLARKSDALE TO CHICAGO By Jared Berkowitz A thesis submitted to the History Department Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey for Undergraduate Departmental Honors Advised by Professor James Livingston and Professor Louise Barnett New Brunswick, New Jersey March 2008 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor James Livingston, my advisor, for allotting me the freedom and direction to complete such a project, Professor Barnett for bringing the close eye of an English scholar to my manuscript, the Aresty Research Center at Rutgers University for their generosity, Greg Johnson, curator of the Blues Archive at the University of Mississippi, for his help in navigating the collection, and my parents for nurturing my love of music and history—encouraging me to combine the two. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 PROLOGUE 4 Chapter 1. Classic Blues: Race Records and Chicago, 1920-1924 5 Chapter 2. “It May Bring Sorrow, It May Bring Cheer,” Delta Blues, 1924-1930 16 Chapter 3. City Folk, Urban Blues, 1930-1935 33 Chapter 4. Standing at the Crossroads, Robert Johnson, 1935-1938 46 EPILOGUE: The Blues Continuum: Muddy Waters, 1941 -1943 64 APPENDIX: The Blues Statement 68 Bibliography 69 Discography 72 That specific remedy for the worldwide epidemic of depression is a gift called the blues. All pop music today—jazz, swing, be-bop, Elvis Presley, the Beatles, the Stones, rock- and-roll, hip-hop, and on and on—is derived from the blues. —Kurt Vonnegut, A Man Without A Country So long, So far away Is Africa. Not even memories alive Save those that history books create, Save those that songs Beat back into the blood— Beat out of blood with words sad-sung In strange un-Negro tongue— So long So far away Is Africa. -

The Blues, Rock-And-Roll, and Racism ◆ 3

The Blues, 1 Rock-and-Roll, and Racism It used to be called boogie-woogie, it used to be “ called blues, used to be called rhythm and blues. It’s called rock now. ” —Chuck Berry A smoke-filled club, the Macomba Lounge, on the South Side of Chicago, late on a Saturday night in 1950. On a small, dimly lit stage behind the bar in the long, nar- row club stood an intense African American dressed in an electric green suit, baggy pants, a white shirt, and a wide, striped tie. He sported a 3-inch pompadour with his hair slicked back on the sides. He gripped an oversized electric guitar—an instrument born in the postwar urban environment—caressing, pulling, pushing, and bending the strings until he produced a sorrowful, razor-sharp cry that cut into his listeners, who responded with loud shrieks. With half-closed eyes, the guitarist peered through the smoke and saw a bar jammed with patrons who nursed half-empty beer bottles. Growling out the lyrics of “Rollin’ Stone,” the man’s face was contorted in a painful expression that told of cot- ton fields in Mississippi and the experience of African Americans in Middle America at midcentury. The singer’s name was Muddy Waters, and he was playing a new, elec- trified music called rhythm and blues, or R&B. The rhythm and blues of Muddy Waters and other urban blues artists served as the foundation for Elvis, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, and most other rock-and-rollers. A subtle blend of African and European traditions, it provided the necessary elements and inspiration for the birth of rock and the success of Chuck Berry and Little Richard.