Linguistic Isolation: Ferdinand De Saussure's Linguistic Theory and the Implications for Historiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Similarities and Differences Between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology

International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature E-ISSN: 2200-3452 & P-ISSN: 2200-3592 www.ijalel.aiac.org.au Similarities and Differences between Simultaneous and Successive Bilingual Children: Acquisition of Japanese Morphology Yuki Itani-Adams1, Junko Iwasaki2, Satomi Kawaguchi3* 1ANU College of Asia & the Pacific, The Australian National University, Canberra, ACT, 2601, Australia 2School of Arts and Humanities, Edith Cowan University, 2 Bradford Street, Mt Lawley WA 6050, Australia 3School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Bullecourt Ave, Milperra NSW 2214, Australia Corresponding Author: Satomi Kawaguchi , E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history This paper compares the acquisition of Japanese morphology of two bilingual children who had Received: June 14, 2017 different types of exposure to Japanese language in Australia: a simultaneous bilingual child Accepted: August 14, 2017 who had exposure to both Japanese and English from birth, and a successive bilingual child Published: December 01, 2017 who did not have regular exposure to Japanese until he was six years and three months old. The comparison is carried out using Processability Theory (PT) (Pienemann 1998, 2005) as a Volume: 6 Issue: 7 common framework, and the corpus for this study consists of the naturally spoken production Special Issue on Language & Literature of these two Australian children. The results show that both children went through the same Advance access: September 2017 developmental path in their acquisition of the Japanese morphological structures, indicating that the same processing mechanisms are at work for both types of language acquisition. However, Conflicts of interest: None the results indicate that there are some differences between the two children, including the rate Funding: None of acquisition, and the kinds of verbal morphemes acquired. -

A Diagrammatic Approach to Peirce's Classifications of Signs

A diagrammatic approach to Peirce’s classifications of signs1 Priscila Farias Graduate Program in Design (SENAC-SP & UFPE) [email protected] João Queiroz Graduate Studies Program on History, Philosophy, and Science Teaching (UFBA/UEFS) Dept. of Computer Engineering and Industrial Automation (DCA/FEEC/UNICAMP) [email protected] © This paper is not for reproduction without permission of the author(s). ABSTRACT Starting from an analysis of two diagrams for 10 classes of signs designed by Peirce in 1903 and 1908 (CP 2.264 and 8.376), this paper sets forth the basis for a diagrammatic understanding of all kinds of classifications based on his triadic model of a sign. Our main argument is that it is possible to observe a common pattern in the arrangement of Peirce’s diagrams of 3-trichotomic classes, and that this pattern should be extended for the design of diagrams for any n-trichotomic classification of signs. Once this is done, it is possible to diagrammatically compare the conflicting claims done by Peircean scholars re- garding the divisions of signs into 28, and specially into 66 classes. We believe that the most important aspect of this research is the proposal of a consolidated tool for the analysis of any kind of sign structure within the context of Peirce’s classifications of signs. Keywords: Peircean semiotics, classifications of signs, diagrammatic reasoning. 1. PEIRCE’S DIAGRAMS FOR 10 CLASSES OF SIGNS In a draft of a letter to Lady Welby composed by the end of December 1908 (dated 24-28 December, L463:132-146, CP 8.342-76, EP2:483-491; we will be referring to this diagram 1. -

The Commutation Test and Chris Bacon's Score for Source Code As

The Commutation Test and Chris Bacon’s Score for Source Code as a Framework for Film Music Pedagogy Aaron Ziegel, Towson University he cinema, whether experienced at the neighborhood multiplex or streamed at home, is arguably the medium through which today’s col- lege-age Americans are most likely to encounter newly composed sym- Tphonic music. Given the ubiquity of the film-viewing experience, students are often eager to learn the tools and methodologies that can equip them to criti- cally assess and more fully comprehend the function of music in movies. The filmSource Code (2011), directed by Duncan Jones and scored by Chris Bacon, provides a particularly effective starting point through which this process can begin.1 This article will discuss the pedagogical potential found in the film’s main titles and the impact of applying a commutation test to this sequence. Although here I address one specific example, the methodology of the commu- tation test is easily adaptable to other circumstances, as the theoretical foun- dation will make clear. While variations on the commutation test are a regular occurrence in many film music classrooms, this essay aims to present an intro- ductory primer that may be of use to instructors interested in an entry point for incorporating film music studies into their teaching. With that in mind, the appendix presents one suggestion for how to create film clips for classroom use. The value of this classroom activity extends beyond providing students with an engaging and memorable learning experience. By situating this analysis I wish to express my gratitude to the many students at Towson University whose feedback and enthusiastic classroom participation, along with suggestions from the anonymous reviewers, helped me to refine the pedagogical approach described in this essay. -

Part 1: Introduction to The

PREVIEW OF THE IPA HANDBOOK Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet PARTI Introduction to the IPA 1. What is the International Phonetic Alphabet? The aim of the International Phonetic Association is to promote the scientific study of phonetics and the various practical applications of that science. For both these it is necessary to have a consistent way of representing the sounds of language in written form. From its foundation in 1886 the Association has been concerned to develop a system of notation which would be convenient to use, but comprehensive enough to cope with the wide variety of sounds found in the languages of the world; and to encourage the use of thjs notation as widely as possible among those concerned with language. The system is generally known as the International Phonetic Alphabet. Both the Association and its Alphabet are widely referred to by the abbreviation IPA, but here 'IPA' will be used only for the Alphabet. The IPA is based on the Roman alphabet, which has the advantage of being widely familiar, but also includes letters and additional symbols from a variety of other sources. These additions are necessary because the variety of sounds in languages is much greater than the number of letters in the Roman alphabet. The use of sequences of phonetic symbols to represent speech is known as transcription. The IPA can be used for many different purposes. For instance, it can be used as a way to show pronunciation in a dictionary, to record a language in linguistic fieldwork, to form the basis of a writing system for a language, or to annotate acoustic and other displays in the analysis of speech. -

Review: Marcello Barbieri (Ed) (2007) Introduction to Biosemiotics. the New Biological Synthesis

tripleC 5(3): 104-109, 2007 ISSN 1726-670X http://tripleC.uti.at Review: Marcello Barbieri (Ed) (2007) Introduction to Biosemiotics. The new biological synthesis. Dordrecht: Springer Günther Witzany telos – Philosophische Praxis Vogelsangstr. 18c A-5111-Buermoos/Salzburg Austria E-mail: [email protected] 1 Thematic background without utterances we act as non-uttering indi- viduals being dependent on the discourse de- Maybe it is no chance that the discovery of the rived meaning processes of a linguistic (e.g. sci- genetic code occurred during the hot phase of entific) community. philosophy of science discourse about the role of This position marks the primary difference to language in generating models of scientific ex- the subject of knowledge of Kantian knowledge planation. The code-metaphor was introduced theories wherein one subject alone in principle parallel to other linguistic terms to denote lan- could be able to generate sentences in which it guage like features of the nucleic acid sequence generates knowledge. This abstractive fallacy molecules such as “code without commas” was ruled out in the early 50s of the last century (Francis Crick). At the same time the 30 years of being replaced by the “community of investiga- trying to establish an exact scientific language to tors” (Peirce) represented by the scientific com- delimit objective sentences from non-objective munity in which every single scientist is able the ones derived one of his peaks in the linguistic place his utterance looking for being integrated turn. in the discourse community in which his utter- ances will be proven whether they are good ar- 1.1 Changing subjects of knowledge guments or not. -

Relational Categories

Gentner, D., & Kurtz, K. (2005). Learning and using relational categories. In W. K. Ahn, R. L. Goldstone, B. C. Love, A. B. Markman & P. W. Wolff (Eds.), Categorization inside and outside the laboratory. Washington, DC: APA. Relational Categories Dedre Gentner and Kenneth J Kurtz Relational Categories This chapter is concerned with the acquisition and use of relational categories. By relational category, we mean a category whose membership is determined by a common relational structure rather than by common properties. For instance, for X to be a bridge, X must connect two other entities or points; for X to be a carnivore, X must eat animals. Relational categories contrast with entity categories such as tulip or camel, whose members share many intrinsic properties. Relational categories cohere on the basis of a core relationship ful- filled by all members. This relation may be situation-specific (e.g., passenger or accident) or enduring (e.g., carnivore or ratio). Relational categories abound in ordinary language. Some are restricted in their arguments: For example, car- nivores are animals who eat other animals. But for many relational catego- ries, the arguments can range widely: for example, a bridge can connect two concrete locations, or two generations, or two abstract ideas. As with bridge, the instances of a relational category can have few or no intrinsic properties in common with one another. Research on categories has mostly ignored relational categories, focusing instead on entity categories-categories that can be characterized in terms of intrinsic similarity among members, like those shown in Figure 9.1. Further, as Moos and Sloutsky (2004) point out, theories of categorization have often oper- ated under the assumption that all concepts are fundamentally alike. -

Whole Language Instruction Vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students

Whole Language Instruction vs. Phonics Instruction: Effect on Reading Fluency and Spelling Accuracy of First Grade Students Krissy Maddox Jay Feng Presentation at Georgia Educational Research Association Annual Conference, October 18, 2013. Savannah, Georgia 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to investigate the efficacy of whole language instruction versus phonics instruction for improving reading fluency and spelling accuracy. The participants were the first grade students in the researcher’s general education classroom of a non-Title I school. Stratified sampling was used to randomly divide twenty-two participants into two instructional groups. One group was instructed using whole language principles, where the children only read words in the context of a story, without any phonics instruction. The other group was instructed using explicit phonics instruction, without a story or any contextual influence. After four weeks of treatment, results indicate that there were no statistical differences between the two literacy approaches in the effect on students’ reading fluency or spelling accuracy; however, there were notable changes in the post test results that are worth further investigation. In reading fluency, both groups improved, but the phonics group made greater gains. In spelling accuracy, the phonics group showed slight growth, while the whole language scores decreased. Overall, the phonics group demonstrated greater growth in both reading fluency and spelling accuracy. It is recommended that a literacy approach should combine phonics and whole language into one curriculum, but place greater emphasis on phonics development. 2 Introduction Literacy is the fundamental cornerstone of a student’s academic success. Without the skill of reading, children will almost certainly have limited academic, economic, social, and even emotional success in school and in later life (Pikulski, 2002). -

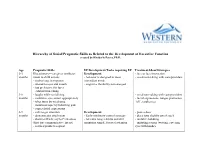

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills As Related to the Development of Executive Function Created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D

Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function created by Kimberly Peters, Ph.D. Age Pragmatic Skills EF Development/Tasks requiring EF Treatment Ideas/Strategies 0-3 Illocutionary—caregiver attributes Development: - face to face interaction months intent to child actions - behavior is designed to meet - vocal-turn-taking with care-providers - smiles/coos in response immediate needs - attends to eyes and mouth - cognitive flexibility not emerged - has preference for faces - exhibits turn-taking 3-6 - laughs while socializing - vocal turn-taking with care-providers months - maintains eye contact appropriately - facial expressions: tongue protrusion, - takes turns by vocalizing “oh”, raspberries. - maintains topic by following gaze - copies facial expressions 6-9 - calls to get attention Development: - peek-a-boo months - demonstrates attachment - Early inhibitory control emerges - place toys slightly out of reach - shows self/acts coy to Peek-a-boo - tolerates longer delays and still - imitative babbling (first true communicative intent) maintains simple, focused attention - imitating actions (waving, covering - reaches/points to request eyes with hands). 9-12 - begins directing others Development: - singing/finger plays/nursery rhymes months - participates in verbal routines - Early inhibitory control emerges - routines (so big! where is baby?), - repeats actions that are laughed at - tolerates longer delays and still peek-a-boo, patta-cake, this little piggy - tries to restart play maintain simple, -

MEANING, SEMIOTECHNOLOGIES and PARTICIPATORY MEDIA Ganaele Langlois

CULTURE MACHINE VOL 12 • 2011 MEANING, SEMIOTECHNOLOGIES AND PARTICIPATORY MEDIA Ganaele Langlois Summary What is the critical purpose of studying meaning in a digital environment which is characterized by the proliferation of meanings? In particular, online participatory media platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, Wikipedia and Twitter offer a constant stream of user-produced meanings. In this new context of seemingly infinite ‘semiotic democracy’ (Fiske, 1987), where anybody can say anything and have a chance to be heard, it seems that the main task is to find ways to deal with and analyze an ever-expanding field of signification. This article offers a different perspective on the question of meaning by arguing that if we are to study meaning to understand the cultural logic of digital environments, we should not focus on the content of what users are saying online, but rather on the conditions within which such a thing as user expression is possible in the first place. That is, this article argues that we should focus less on signification, and more on the question of regimes of the production and circulation of meaning. By expanding the question of meaning and using it to explore commercial participatory media platforms, this article offers a new framework for looking at online communication: one that decentres human subjects from the production of meaning and that acknowledges the technocultural dimension of meaning as constituted by a range of heterogeneous representational and informational technologies, cultural practices and linguistic values. Online participatory media platforms offer an exemplar of the new conditions of the production and circulation of meaning beyond the human level: they offer rich environments where user input is constantly augmented, ranked, classified and linked with other types of content. -

Semiosphere As a Model of Human Cognition

494 Aleksei Semenenko Sign Systems Studies 44(4), 2016, 494–510 Homo polyglottus: Semiosphere as a model of human cognition Aleksei Semenenko Department of Slavic and Baltic Languages Stockholm University 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Th e semiosphere is arguably the most infl uential concept developed by Juri Lotman, which has been reinterpreted in a variety of ways. Th is paper returns to Lotman’s original “anthropocentric” understanding of semiosphere as a collective intellect/consciousness and revisits the main arguments of Lotman’s discussion of human vs. nonhuman semiosis in order to position it in the modern context of cognitive semiotics and the question of human uniqueness in particular. In contrast to the majority of works that focus on symbolic consciousness and multimodal communication as specifi cally human traits, Lotman accentuates polyglottism and dialogicity as the unique features of human culture. Formulated in this manner, the concept of semiosphere is used as a conceptual framework for the study of human cognition as well as human cognitive evolution. Keywords: semiosphere; cognition; polyglottism; dialogue; multimodality; Juri Lotman Th e concept of semiosphere is arguably the most infl uential concept developed by the semiotician and literary scholar Juri Lotman (1922–1993), a leader of the Tartu- Moscow School of Semiotics and a founder of semiotics of culture. In a way, it was the pinnacle of Lotman’s lifelong study of culture as an intrinsic component of human individual -

'Langue' and 'Langage

FOURNET, Arnaud. Some comparative and historical considerations about Ferdinand de Saussure's distinction between ‘langue’ and ‘langage’. ReVEL , vol. 8, n. 14, 2010. [www.revel.inf.br/eng]. SOME COMPARATIVE AND HISTORICAL CONSIDERATIONS ABOUT FERDINAND DE SAUSSURE ’S DISTINCTION BETWEEN ‘LANGUE ’ AND ‘LANGAGE ’ Arnaud Fournet 1 [email protected] ABSTRACT : Modern French has two words: langue and langage when English has only one: language , originally a loanword from Old French. The article investigates when and how French gradually used two words to distinguish the concept of a particular language ( langue ) and that of speech ability ( langage ). This split started around 1600 and was permanently established around 1800. KEYWORDS : Language; Structuralism; de Saussure. 1. ABOUT THE ENGLISH WORD ‘LANGUAGE ’ The present article originates in my personal realization that English only has one word: language whereas French has two words: langue and langage to describe linguistic activity, behavior, competence or faculty 2, in spite of the quite obvious historical fact that the English word is a loanword from (Old) French 3. So I set about looking for the reasons why the difference exists and what particular theoretical features it may entail. English somehow misses a word and it is interesting to investigate the causes and some potential consequences of that lexical want. It is worth noting that, following the impulse of Old French, several modern Romance languages display a similar difference between langue 4 and langage 5. The word langue is the 1 PhD from Université René Descartes. 2 Depending on the theoretical preferences of authors. 3 The English word begins to be attested in the time bracket: 1250-1300. -

The Semiotics of Tourism Own Provincial Expectations

From: Framing The Sign: Criticism and Its Institutions © University of Oklahoma Press, 1990 The Semiotics of Tourism own provincial expectations. The French chanteuse singing English with a French accent seems more charmingly French JONATHAN CULLER than one who simply sings in French.1 Tourism is a practice of considerable cultural and economic There are perhaps interesting reasons why this should be so, importance and, unlike a good many manifestations of but Boorstin does not stop to inquire. ‘Tourist “attractions” offer contemporary culture, is well known in some guise to every an elaborately contrived indirect experience, an artificial product literary or cultural critic. Some may claim ignorance of to be consumed in the very places where the real thing is free as television or rock music or fashion, but all have been tourists and air’. What could be more foolish than a tourist paying through have observed tourists. Yet despite the pervasiveness of tourism the nose for an artificial substitute when the real thing, all around and its centrality to our conception of the contemporary world him, is as free as the air? (for most of us, the world is more imperiously an array of places This discussion is not untypical of what passes for cultural one might visit than it is a configuration of political or economic criticism: complaints about the tawdriness or artificiality of forces), tourism has been neglected by students of culture. modern culture which do not attempt to account for the curious Unlike the cinema, popular romance, or even video, tourism has facts they rail against and offer little explanation of the cultural scarcely figured in the theoretical discussions and debates about mechanisms that might be responsible for them.