Beech Bark Disease Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Pupillarial Scale Insect (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Eriococcidae) from Angophora in Coastal New South Wales, Australia

Zootaxa 4117 (1): 085–100 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4117.1.4 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:5C240849-6842-44B0-AD9F-DFB25038B675 A new pupillarial scale insect (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Eriococcidae) from Angophora in coastal New South Wales, Australia PENNY J. GULLAN1,3 & DOUGLAS J. WILLIAMS2 1Division of Evolution, Ecology & Genetics, Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Acton, Canberra, A.C.T. 2601, Australia 2The Natural History Museum, Department of Life Sciences (Entomology), London SW7 5BD, UK 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new scale insect, Aolacoccus angophorae gen. nov. and sp. nov. (Eriococcidae), is described from the bark of Ango- phora (Myrtaceae) growing in the Sydney area of New South Wales, Australia. These insects do not produce honeydew, are not ant-tended and probably feed on cortical parenchyma. The adult female is pupillarial as it is retained within the cuticle of the penultimate (second) instar. The crawlers (mobile first-instar nymphs) emerge via a flap or operculum at the posterior end of the abdomen of the second-instar exuviae. The adult and second-instar females, second-instar male and first-instar nymph, as well as salient features of the apterous adult male, are described and illustrated. The adult female of this new taxon has some morphological similarities to females of the non-pupillarial palm scale Phoenicococcus marlatti Cockerell (Phoenicococcidae), the pupillarial palm scales (Halimococcidae) and some pupillarial genera of armoured scales (Diaspididae), but is related to other Australian Myrtaceae-feeding eriococcids. -

Investigating the Relationship Between Cryptococcus Fagisuga and Fagus Grandifolia in Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Portland State University PDXScholar Biology Faculty Publications and Presentations Biology 1-1-2002 Investigating the Relationship Between Cryptococcus Fagisuga and Fagus Grandifolia in Great Smoky Mountains National Park Ashley B. Morris University of Florida Randall L. Small University of Tennessee - Knoxville Mitchell B. Cruzan Portland State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/bio_fac Part of the Plant Biology Commons, and the Plant Breeding and Genetics Commons Citation Details Morris A.B., R.L. Small, and M.B. Cruzan. 2002. Investigating the Relationship Between Cryptococcus Fagisuga and Fagus Grandifolia in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Southeastern Naturalist 1:415-424. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2002 SOUTIIE;\STERN NATURAWT 114):4 15--124 INVESTIGATING THE RELATIONSHJP BETWEEN CRYPTOCOCCUS FAG1SUGA A D FAGUS GRANDlFOLlA IN GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK A SIILEY B . M ORKIS " R ANDAll. L. SMALL 1. AND MITCIIELL B. CRUZAr\ 2.. I AI3STRACT - The high elcvmioll beech ga ps of lhc Grc<l1 Smoky Mountains have become the kil ling fron t of beech b'lrk di sc.lsc. Th is insectffullgill pat hoge n WIIS introd uced into Nova Scotia in the late 1800':-.. and has since spread so uthward to the SOllth l! n1 Appul:H.: hi:ub. In affected stands. mortality of beech stems fre quently approaChes 90 lO 100 percenl. -

Fungi and Their Potential As Biological Control Agents of Beech Bark Disease

Fungi and their potential as biological control agents of Beech Bark Disease By Sarah Elizabeth Thomas A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences Royal Holloway, University of London 2014 1 DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, Sarah Elizabeth Thomas, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: _____________ Date: 4th May 2014 2 ABSTRACT Beech bark disease (BBD) is an invasive insect and pathogen disease complex that is currently devastating American beech (Fagus grandifolia) in North America. The disease complex consists of the sap-sucking scale insect, Cryptococcus fagisuga and sequential attack by Neonectria fungi (principally Neonectria faginata). The scale insect is not native to North America and is thought to have been introduced there on seedlings of F. sylvatica from Europe. Conventional control strategies are of limited efficacy in forestry systems and removal of heavily infested trees is the only successful method to reduce the spread of the disease. However, an alternative strategy could be the use of biological control, using fungi. Fungal endophytes and/or entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) could have potential for both the insect and fungal components of this highly invasive disease. Over 600 endophytes were isolated from healthy stems of F. sylvatica and 13 EPF were isolated from C. fagisuga cadavers in its centre of origin. A selection of these isolates was screened in vitro for their suitability as biological control agents. Two Beauveria and two Lecanicillium isolates were assessed for their suitability as biological control agents for C. -

Nutritional Effects on Causal Organisms of Beech Bark Disease in An

NUTRITIONAL EFFECTS ON CAUSAL ORGANISMS OF BEECH BARK DISEASE IN AN AFTERMATH FOREST by Gretchen A. Dillon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry Syracuse, New York December 2019 Department Forest and Natural Resources Management Approved by: Ruth Yanai, Major Professor Jeffrey Garnas, Examining Committee Martin Dovciak, Examining Committee Chair Christopher Nowak, Department Chair Scott S. Shannon, Dean, the Graduate School © 2019 Copyright G.A. Dillon All rights reserved Acknowledgements I would especially like to thank the esteemed faculty at SUNY-ESF including Dr. Ruth Yanai, Dr. Mariann Johnston, and Dr. Thomas Horton for their patient assistance, and Dr. Greg McGee for securing microscopes and work space. Thank you to Christine Costello of the USFS; to my dedicated lab cohort, Yang Yang, Daniel Hong, Madison Morley, Alex Young, Alexandrea Rice, Jenna Zukswert, and Thomas Mann for countless Crayola crayon exercises and emotional support. Thank you to Mary Hagemann whose invaluable efforts help the B9 lab run more smoothly. This project could not have been completed without the help of the following summer, undergraduate, high school, and citizen scientist research technicians: Steve Abrams, Shaheemah Ashkar, Harshdeep Banga, Stephanie Chase, Kien Dao, Madeleine Desrochers, Imani Diggs, Bryn Giambona, Lia Ivanick, Abby Kambhampaty, Milda Kristupaitis, Vizma Leimanis, Grace Lockwood, Michael Mahoney, Charlie Mann, Allison Laplace McKenna, Julie Romano, Jason Stoodley, Emma Tucker, Trey Turnbalcer , and Sara Wasserman. Thank you to my family, biological and chosen, especially Lauren Martin, Sarah Dulany-Gring, my husband Michael, and Wilhelmina. -

Beech Bark Disease Distribution and Resistance in Michigan and Fungal Endophyte Ecology of Resistant and Susceptible Beech (Fagus Grandifolia Ehrh.)

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports - Open Reports 2013 Beech bark disease distribution and resistance in Michigan and fungal endophyte ecology of resistant and susceptible beech (Fagus grandifolia Ehrh.) Rachel E. Griesmer-Zakhar Michigan Technological University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons Copyright 2013 Rachel E. Griesmer-Zakhar Recommended Citation Griesmer-Zakhar, Rachel E., "Beech bark disease distribution and resistance in Michigan and fungal endophyte ecology of resistant and susceptible beech (Fagus grandifolia Ehrh.)", Master's Thesis, Michigan Technological University, 2013. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etds/455 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etds Part of the Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons, and the Plant Pathology Commons BEECH BARK DISEASE DISTRIBUTION AND RESISTANCE IN MICHIGAN AND FUNGAL ENDOPHYTE ECOLOGY OF RESISTANT AND SUSCEPTIBLE BEECH (FAGUS GRANDIFOLIA EHRH.). By Rachel E. Griesmer-Zakhar A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In Forest Ecology and Management MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Rachel E. Griesmer-Zakhar This thesis has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Forest Ecology and Management. School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science Thesis Advisor: Andrew J. Storer Committee Member: Dana L. Richter Committee Member: Thomas P. Snyder Committee Member: Gerard C. Adams School Dean: Terry L. Sharik Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................................................ -

Beech Bark Disease (Neonectria Spp. and Cryptococcus Fagisuga) Forest Health and Monitoring Division

Maine State Library Digital Maine Forest Service Documents Maine Forest Service 2-2018 Beech bark disease (Neonectria spp. and Cryptococcus fagisuga) Forest Health and Monitoring Division Maine Forest Service Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalmaine.com/for_docs Recommended Citation Forest Health and Monitoring Division; Maine Forest Service; and Department of Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry, "Beech bark disease (Neonectria spp. and Cryptococcus fagisuga)" (2018). Forest Service Documents. 97. http://digitalmaine.com/for_docs/97 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Maine Forest Service at Digital Maine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Forest Service Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Maine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maine Forest Service Beech bark disease (Neonectria spp. and Cryptococcus fagisuga) Insect and Disease Laboratory 50 Hospital Street, Augusta, Maine 04330-6598 ● (207) 287-2791 ●www.maineforestservice.gov Hosts: Beech (Fagus grandifolia), European beech (Fagus sylvatica). General information: Beech bark disease (BBD) affects American beech trees throughout much of their natural range in North America. The disease is typically a result of the infestation and feeding by the beech bark scale, Cryptococcus fagisuga, predisposing beech trees to infection by two fungi: Neonectria coccinea var. faginta and sometimes N. galligena. Another scale, Xylococculus betulae, has been observed to be commonly associated with the disease in Maine, but its significance to the disease complex is unknown. The BBD complex arrived ca. 1920 on a shipment of infected European beech seedlings from Europe. Since its introduction, BBD has spread steadily and is now found as far west as Wisconsin. -

Beech Bark Disease in Michigan: Distribution, Impacts, and Dynamics

BEECH BARK DISEASE IN MICHIGAN: DISTRIBUTION, IMPACTS and DYNAMICS By James B. Wieferich A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Forestry - Master of Science 2013 ABSTRACT BEECH BARK DISEASE IN MICHIGAN: DISTRIBUTION, IMPACTS and DYNAMICS By James B. Wieferich Beech bark disease (BBD), a Neonectria fungal disease mediated by an invasive sap- feeding beech scale insect (Cryptococcus fagisuga Lind.), continues to affect American beech (Fagus grandifolia) in North America. Beech scale was first identified in Upper and Lower Michigan in 2000. Annual monitoring indicates the rate of spread of the advancing front (beech scale infestation) from 2005 to 2012, varies among Lower Michigan populations, ranging from <1 km to 14.3 km per year. Spread rates are more consistent in Upper Michigan, ranging from 3 to 11 km per year. In 2002, 62 long term impact sites were established in areas with low, moderate or high beech basal area and beech scale infestations ranging from absent to heavy to collect baseline data on beech condition, overstory and understory species composition and coarse woody material (CWM). Twelve beech trees per site (744 total) were also tagged for future evaluation. In 2012, I re-visited the original 62 sites to assess impacts of BBD and determine if beech basal area, initial beech scale infestation (in 2002) or differences between Upper and Lower Michigan affected beech mortality, CWM or related variables. In Upper Michigan, up to 55.6% of beech stems and 92.4% of beech basal area have died. In Lower Michigan, however, the highest mortality recorded in a site was 38.9% and dead beech basal area did not exceed 25.6% in any site. -

Beech Bark Disease (Cryptococcus Fagisuga and Neonectria Spp.)

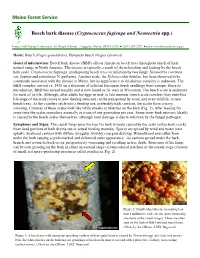

Maine Forest Service Beech bark disease (Cryptococcus fagisuga and Neonectria spp.) Insect and Disease Laboratory 50 Hospital Street , Augusta, Maine, 04330-6598 ● (207) 287-2791 ●www.maineforestservice.gov Hosts: Beech (Fagus grandifolia), European beech (Fagus sylvatica). General information: Beech bark disease (BBD) affects American beech trees throughout much of their natural range in North America. The disease is typically a result of the infestation and feeding by the beech bark scale, Cryptococcus fagisuga, predisposing beech trees to infection by two fungi: Neonectria coccinea var. faginta and sometimes N. galligena. Another scale, the Xylococculus betulae, has been observed to be commonly associated with the disease in Maine, but its significance to the disease complex is unknown. The BBD complex arrived ca. 1920 on a shipment of infected European beech seedlings from Europe. Since its introduction, BBD has spread steadily and is now found as far west as Wisconsin. The beech scale is sedentary for most of its life. Although, after adults lay eggs in mid- to late summer, beech scale crawlers (tiny mite-like life stage of the scale) move to new feeding sites and can be transported by wind, and even wildlife, to new beech trees. As the crawlers settle into a feeding site, preferably bark crevices, the scales form a waxy covering. Colonies of these scales look like white streaks or blotches on the bark (Fig. 1). After feeding for some time the scales reproduce asexually at a rate of one generation per year. Some inner-bark necrosis (death) is caused by the beech scales themselves, although most damage is due to infection by the fungal pathogen. -

Comparative Densities of Beech Scale, Cryptococcus

422 Florida Entomologist 95(2) June 2012 COMPARATIVE DENSITIES OF BEECH SCALE, CRYPTOCOCCUS FAGISUGA, (HEMIPTERA: ERIOCOCCIDAE) IN THE COUNTRY OF GEORGIA AND MASSACHUSETTS (USA), PARTS OF ITS NATIVE AND INVADED RANGES, ON TWO SPECIES OF BEECH R. G. VAN DRIESCHE1 AND G. JAPOSHVILI2 1PSIS/Division of Entomology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003, USA 2Entomology and Biocontrol Research Centre, Agricultural University of Georgia, Tbilisi, 0131, Georgia ABSTRACT The Caucasus Mountains in the country of Georgia are part of the native range of beech scale (Cryptococcus fagisuga) and Massachusetts (United States) is part of the invaded range of this species. As background to determine if the native range of this scale might be a source of natural enemies useful for correcting the ecological damage caused by beech scale in North America to America beech (Fagus grandifolia) comparative scale densities were measured in both locations in natural forest stands of F. grandifolia in Massachusetts and F. orientalis in Georgia. Average diameter at breast height (DBH) and health values were also compared. Scale densities were found to be 45.4-fold higher per unit area of bark in Massachusetts on F. grandifolia than in the country of Georgia on F. orientalis. Also, F. orientalis trees at sample sites in Georgia were 2.9-fold larger in DBH and much healthier that were F. grandifolia trees in Massachusetts. These data suggest that either F. orientalis is more resistant to beech bark disease than F. grandifolia or key natural enemies found in Georgia are miss- ing in Massachusetts, or both. Cage exclusion studies are underway, separate from results reported here, to separate the effects of tree resistance and natural enemies. -

Insects: Beech Scale, a Potential Threat in the Landscape

SP503-H Insects Beech Scale, A Potential Threat in the Landscape Frank Hale, Professor, Greg Wiggins, Research Associate, Paris Lambdin, Professor, and Jerome Grant, Professor Entomology and Plant Pathology The beech scale (Cryptococcus fagisuga Lindinger) was rst found in the U.S. in Massachusetts and Maine in the 1930s. This European insect feeds on American and European beech by inserting its long, needle-like, piercing-sucking mouthparts (or stylets) through the smooth bark, where the scale remains station- ary throughout its life. This persistent feeding can stress the tree, especially during drought conditions, and reduce the overall vigor and quality of beech. However, it is this insect’s association with two species of fungi, Nectria galligena (a native fungus) and Nectria coccinea var. faginata (an introduced European fungus), that can cause mortality of beech. As it feeds, the scale repeat- edly removes and reinserts its mouthparts, wounding the tree and providing entry sites for the introduction of these two fungal pathogens. Beech scale eggs and crawlers on bark of beech. The beech scale and the pathogens are the causal agents of beech bark disease, which has killed large numbers of trees throughout eastern North America. Beech scale and beech bark disease have gradually spread southward and both were reported old or historic homes and homesteads. While young beech trees in 1993 in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, where are not often killed by beech bark disease, they often succumb beech mortality has been documented. The current range of once they reach maturity. Because the disease is so widespread beech scale and beech bark disease in Tennessee is unclear, but it throughout the forests of the eastern U.S., beech bark disease is probably found throughout areas along the border of Tennes- threatens beech in the landscape as well. -

NAME of SPECIES: Nectria Coccinea Var

NAME OF SPECIES: Nectria coccinea var. fagisuga Lohman, Watson and Ayes and Cryptococcus fagisuga Lind. Synonyms: none Common Name: Beech bark disease A. CURRENT STATUS AND DISTRIBUTION I. In Wisconsin? 1. YES NO X 2. Abundance: 3. Geographic Range: 4. Habitat Invaded: 5. Historical Status and Rate of Spread in Wisconsin: 6. Proportion of potential range occupied: II. Invasive in Similar Climate YES X NO Zones United States: New England, New York (1960), Pennsylvania (1975), West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Ohio, Michigan (2000) Canada: Nova Scotia (1890), eastern Canada (1930’s), Quebec III. Invasive in Similar Habitat YES X NO Types IV. Habitat Affected 1. Host plants: Fagus grandifolia (American beech) 2. Conservation significance of threatened habitats: Beech is frequently the primary nut producer in northern hardwood stands, and this hard mast provides an important food source for many animals. V. Native Habitat 1. Countries: Europe 2. Hosts: Fagus sylvatica (European beech) VI. Legal Classification 1. Quarantined species? YES NO X 2. By what states, countries? B. ESTABLISHMENT POTENTIAL AND LIFE HISTORY TRAITS I. Life History 1. Type of pathogen: Ascomycotina: Hypocreales 2. Time to Maturity: There is at least a 1 year time delay between the appearance of its vector, Cryptococcus fagisuga, and appearance of the fungus. 3. Methods of Spread: Vectored by the exotic beech scale insect: C. fagisuga Lind. Birds probably transport crawlers short distances, and perhaps long distances during migratory flights. The fungal spores are disseminated by rain splash or by the wind and penetrate into the tree through wounds created by the scale insect.Humans move infested wood. -

MANAGEMENT of BEECH STANDS INFECTED by CRYPTOCOCCUS FAGISUGA in WEST GERMANS Hermann ~Ogenschutz'

I Rssearch on Beech Bark Disease: Fwest-Disease Relationships MANAGEMENT OF BEECH STANDS INFECTED BY CRYPTOCOCCUS FAGISUGA IN WEST GERMANS Hermann ~ogenschutz' Abstract.--Beech trees in an experimental plot in the Odenwald (southwest Germany), with different intensities of attack by Cryptococcus fagisuga Lind. since at least 1970, were observed from 1972 until 1982 in order to ascertain the role of scale insects in beech bark disease and to facilitate decisions for the management of infested stands. At the beginning of the research 13% of the dominant trees were infested by C. fagisw. Until 1979 the attack decreased continuously, only in the dry years 1975 and 1976 did the number of trees with moderate attack increase. Since 1980 new infestations on previously uninfested trees have been observed. Eighteen per cent of the trees, which had been moderately or heavily attacked in 1972, died during the following years. The recovered trees exhibited pathological bark induced by the sucking activity of the scale insects. According to these results, practising foresters are recommended not to do a sanitation felling, if locally not more than 6% of the beech trees reach the attack class moderate or heavy. INTRODUCTION a sample area within a stand heavily infested by the beech scale, Cryptococcus fagisuga Practising foresters in Germany are Lind. The trees selected and marked for advised by the forest protection authorities observation have been checked at annual to fell beech trees suffering heavily from intervals since 1972. The followinn results beech bark disease immediately in order to are a supplement to those obtained by Rhumbler avoid losses in timber value and to eliminate (1931) in north Germany in the first quarter of sources of infection.