Behavioral Responses to Numerical Differences When Two Invasive Ants Meet: the Case of Lasius Neglectus and Linepithema Humile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Guide of Common Ants

J U L Y / A U G 2 0 0 3 N P M A L I B R A R Y U P D A T E Insert this update into the NPMA Pest Management Library, which can be Updatepurchased from the Resource Center. phone: 703-573-8330 fax: 703-573-4116 Common Ants: A Pull-Out Guide for Use in the Field This Library Update is designed to of acrobat ants. Workers are 1/16” to 1/8” assist technicians in identification and in length and are normally brown to control of ants while servicing accounts. black in color. The pedicel, or front joint This update is not designed for of the abdomen has two nodes or instruction in basic ant biology, segments. Looking down on the ant nomenclature of the anatomy of the ant, under hand lens magnification, one pair or to be used as a key. For more detailed of spines is found on the thorax. Various information on those topics, refer to the species of acrobat ants are found Field Guide or other technical materials. throughout the United States. In the field, a great aid to identification Acrobat ants are named for their is the use of a hand lens. Many of these tendency to raise their abdomens in the ants are small and positive identification air when disturbed. As the abdomen is is not easy without a hand lens. This heart shaped and is frequently black and article focuses on common, non-wood- shiny, the acrobat motion is readily destroying ants, including: acrobat, observable. -

Taxonomy and Distribution of the Argentine Ant, Linepithema Humile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

SYSTEMATICS Taxonomy and Distribution of the Argentine Ant, Linepithema humile (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) ALEXANDER L. WILD Department of Entomology, University of California at Davis, Davis, CA 95616 Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 97(6): 1204Ð1215 (2004) ABSTRACT The taxonomy of an invasive pest species, the Argentine ant, is reviewed. Linepithema humile (Mayr) 1868 is conÞrmed as the valid name for the Argentine ant. Morphological variation and species boundaries of L. humile are examined, with emphasis on populations from the antÕs native range in southern South America. Diagnoses and illustrations are provided for male, queen, and worker castes. Collection records of L. humile in South America support the idea of a native distribution closely associated with major waterways in lowland areas of the Parana´ River drainage, with recent intro- ductions into parts of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. KEY WORDS Argentine ant, Linepithema humile, taxonomy, invasive species THE ARGENTINE ANT, Linepithema humile (Mayr) 1868, MCSN, MCZC, MHNG, MZSP, NHMB, NHMW, and is among the worldÕs most successful invasive species. USNM; see below for explanation of abbreviations). This native South American insect has become a cos- Taxonomic confusion over L. humile extends be- mopolitan pest, particularly in the Mediterranean cli- yond museum collections. At least one important mates of North America, Chile, South Africa, Austra- study, seeking to explain Argentine ant population lia, and southern Europe (Suarez et al. 2001). regulation in the native range through phorid para- Argentine ants have been implicated in the decline of sitism (Orr and Seike 1998), initially targeted the native arthropod (Cole et al. 1992) and vertebrate wrong Linepithema species (Orr et al. -

The Case of the Argentine Ant in Vineyards of Northern Argentina

insects Article Growing Industries, Growing Invasions? The Case of the Argentine Ant in Vineyards of Northern Argentina Maria Schulze-Sylvester 1,* ID , José A. Corronca 1 ID and Carolina I. Paris 2 1 FCN-IEBI (Instituto para el Estudio de la Biodiversidad de Invertebrados), CONICET CCT-Salta, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Salta, Av. Bolivia 5150, CP 4400 Salta, Argentina; [email protected] 2 Departamento de Ecología, Genética y Evolución, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Buenos Aires, 1428 Buenos Aires, Argentina; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +54-387-425-5472 Received: 10 December 2017; Accepted: 23 January 2018; Published: 29 January 2018 Abstract: The invasive Argentine ant causes ecological and economic damage worldwide. In 2011, this species was reported in vineyards of Cafayate, a wine-producing town in the Andes, Argentina. While the local xeric climate is unsuitable for Argentine ants, populations could establish in association with vineyards where human activity and irrigation facilitate propagule introduction and survival. In 2013–2014, we combined extensive sampling of the area using ant-baits with monitoring of the change in land use and vineyard cultivated area over the past 15 years. Our results revealed that the species has thus far remained confined to a relatively isolated small area, owing to an effective barrier of dry shrublands surrounding the infested vineyards; yet the recent expansion of vineyard acreage in this region will soon connect this encapsulated area with the rest of the valley. When this happens, vulnerable ecosystems and the main local industry will be put at risk. -

US EPA-Pesticides; Disodium Octaborate Tetrahydrate

EFFICACY REVIEW DATE: IN 4-30-01 OUT 6-21-01 FILE OR REG. NO. 69529-1 PETITION OR EXP. PERMIT NO. DATE DIV. RECEIVED April 19, 2001 DATE OF SUBMISSION April 18, 2001 DATE SUBMISSION ACCEPTED TYPE PRODUCT(S): (I,)D, H, F, N, R, S DATA ACCESSION NO(S). 453568-01;D274488;S596027;Case#046539;AC:301 PRODUCT MGR. NO. 03-Layne/Quarles PRODUCT NAME(S) Pestbor COMPANY NAME Quality Borate Company SUBMISSION PURPOSE Provide performance data in reprint supporting claims for Argentine ant, pharaoh ant and Tap- inoma melanocephalum for formulated products. CHEMICAL & FORMULATION Disodium octaborate tetrahydrate 98% (30 lbs./cu.ft. bulk density manufacturing concentrate) CONCLUSIONS & RECOMMENDATIONS The data presented in EPA Accession (MRID) Number 453568-01, having been obtained from the reprint art- icle titled “Laboratory Evaluation of a Boric Acid Liquid Bait on Colonies of Tapinoma melanocephalum, Argentine Ants and Pharaoh Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)S, which meets the requirements of § 11(b)(1)-(7) on p. 268 and the standard of § 95-11(c)(3)(b) on pp. 270-1 of the Product Performance Guidelines, are adequate to sup- port the registration of the subject product, the sole use for this formulation being for the manufacturing of end use insecticidal products, more specifically baits. The cited data (to be contin'd) is far more than is necessary to establish usefulness of this form- ulation for the making of insecticidal baits. Results with the 3 species included in the testing were as follows: Tapinoma melanocephalum workers were reduced by 97% -

Above-Belowground Effects of the Invasive Ant Lasius Neglectus in an Urban Holm Oak Forest

U B Universidad Autónoma de Barce lona Departamento de Biología Animal, de Biología Vegetal y de Ecología Unidad de Ecología Above-belowground effects of the invasive ant Lasius neglectus in an urban holm oak forest Tesis doctoral Carolina Ivon Paris Bellaterra, Junio 2007 U B Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona Departamento de Biología Animal, de Biología Vegetal y de Ecología Unidad de Ecología Above-belowground effects of the invasive ant Lasius neglectus in an urban holm oak forest Memoria presentada por: Carolina Ivon Paris Para optar al grado de Doctora en Ciencias Biológicas Con el Vº. Bº.: Dr Xavier Espadaler Carolina Ivon Paris Investigador de la Unidad de Ecología Doctoranda Director de tesis Bellaterra, Junio de 2007 A mis padres, Andrés y María Marta, y a mi gran amor Pablo. Agradecimientos. En este breve texto quiero homenajear a través de mi más sincero agradecimiento a quienes me ayudaron a mejorar como persona y como científica. Al Dr Xavier Espadaler por admitirme como doctoranda, por estar siempre dispuesto a darme consejos tanto a nivel profesional como personal, por darme la libertad necesaria para crecer como investigadora y orientarme en los momentos de inseguridad. Xavier: nuestras charlas más de una vez trascendieron el ámbito académico y fue un gustazo escucharte y compartir con vos algunos almuerzos. Te prometo que te enviaré hormigas de la Patagonia Argentina para tu deleite taxonómico. A Pablo. ¿Qué puedo decirte mi amor qué ya no te haya dicho? Gracias por la paciencia, el empuje y la ayuda que me diste en todo momento. Estuviste atento a los más mínimos detalles para facilitarme el trabajo de campo y de escritura. -

Argentine Ant

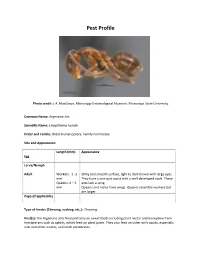

Pest Profile Photo credit: J.A. MacGown, Mississippi Entomological Museum, Mississippi State University Common Name: Argentine Ant Scientific Name: Linepithema humile Order and Family: Order Hymenoptera; Family Formicidae Size and Appearance: Length (mm) Appearance Egg Larva/Nymph Adult Workers: 2 -3 Shiny and smooth surface; light to dark brown with large eyes. mm They have a one-part waist with a well-developed node. These Queens: 4 – 6 ants lack a sting. mm Queens and males have wings. Queens resemble workers but are larger. Pupa (if applicable) Type of feeder (Chewing, sucking, etc.): Chewing Host(s): The Argentine ants feed primarily on sweet foods including plant nectar and honeydew from hemipterans such as aphids, which feed on plant juices. They also feed on other arthropods, especially ants and other insects, and small vertebrates. Description of Damage (larvae and adults): This species is an invasive and widespread pest with significant impacts on arthropod, vertebrate, and plant communities, therefore disrupting ecosystems. They also have significant impacts on agriculture and urban and residential areas. These ants often occur in high densities, especially in urban areas where water is available. These ants do come into homes in search of food and water. They tend and protect aphid and scale pests on a variety of plants from which the ants get honeydew. The Argentine ant is an invasive species, native of South America. This species has spread to the southern USA and is currently found in Arizona, California, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, Oregon, Texas, and Washington states. References: Argentine ant, Texas Invasive Species. (2014). Retrieved from http://www.tsusinvasives.org/home/database/linepithema-humile Fisher, B.L. -

I. Petiole Node II. Tip of Abdomen IV. Length of Antennae Guide to Vineyard Ant Identification III. Shape of Thorax

Guide to Vineyard Ant Identification head abdomen Monica L. Cooper, Viticulture Farm Advisor, Napa County Lucia G. Varela, North Coast IPM Advisor thorax I. Petiole node One Node Two nodes Go to II Subfamily Myrmicinae Go to V II. Tip of abdomen Circle of small hairs present Circle of small hairs absent Subfamily Formicinae Subfamily Dolichoderinae Go to III Argentine Ant (Linepithema humile) III. Shape of thorax Thorax uneven Thorax smooth and rounded Go to IV Subfamily Formicinae Carpenter ant (Camponotus spp.) IV. Length of antennae Antennae not much longer than length of head Antennae much longer than length of head Subfamily Formicinae Subfamily Formicinae Field or Gray Ant (Formica spp.) False honey ant (Prenolepis imparis) head abdomen Petiole with two nodes Subfamily Myrmicinae (V-VIII) thorax V. Dorsal side of Thorax & Antennae One pair of spines on thorax No spines on thorax 12 segmented antennae 10 segmented antennae Go to VI Solenopsis molesta and Solenopsis xyloni VI. Underside of head No brush of bristles Brush of long bristles Go to VII Harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex californicus and P. brevispinosis) VII. Head and Thorax With hairs Without hairs Go to VIII Cardiocondyla mauritanica VIII. Head and Thorax With many parallel furrows Without parallel furrows Profile of thorax rounded Profile of thorax not evenly rounded Pavement ant (Tetramorium “species E”) Pheidole californica Argentine Ant (Linepithema humile), subfamily Dolichoderinae Exotic species 3-4 mm in length Deep brown to light black Move rapidly in distinct trails Feed on honeydew Shallow nests (2 inches from soil surface) Alex Wild Does not bite or sting Carpenter Ant (Camponotus spp.), subfamily Formicinae Large ant: >6 mm in length Dark color with smooth, rounded thorax Workers most active at dusk and night One of most abundant and widespread genera worldwide Generalist scavengers and predators: feed on dead and living insects, nectar, fruit juices and Jack K. -

Behavioral and Genetic Differentiation Between Native and Introduced Populations of the Argentine Ant

Biological Invasions 1: 43–53, 1999. © 1999 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Behavioral and genetic differentiation between native and introduced populations of the Argentine ant ∗ Andrew V. Suarez , Neil D. Tsutsui, David A. Holway & Ted J. Case Department of Biology 0116, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0116, USA; ∗Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]; fax: +1-619-534-7108) Received 9 June 1998; accepted in revised form 22 February 1999 Key words: Argentine ant, biological invasions, competition, invasive ants, Linepithema humile, microsatellites, nestmate recognition, population bottleneck, unicoloniality Abstract In this paper, we examine the hypothesis that reduced intraspecific aggression underlies the competitive prowess of Argentine ants in their introduced range. Specifically, we test three predictions of this hypothesis by comparing the genetic diversity, behavior, and ecology of Argentine ants in their native range to introduced populations. Differences between native and introduced populations of Argentine ants were consistent with our predictions. Introduced populations of the Argentine ant appear to have experienced a population bottleneck at the time of introduction, as evidenced by much reduced variation in polymorphic microsatellite DNA markers. Intraspecific aggression was rare in introduced populations but was common in native populations. Finally, in contrast to the Argentine ant’s ecological dominance throughout its introduced range, it did not appear dominant in the native ant assemblages studied in Argentina. Together these results identify a possible mechanism for the widespread success of the Argentine ant in its introduced range. Introduction Studies that compare the ecology of invasive species between their introduced and native ranges can be par- Despite the widespread problems associated with bio- ticularly insightful. -

Managing Household Ant Pests Bastiaan M

B-6183 12-05 Managing Household Ant Pests Bastiaan M. Drees* n nature, ants are generally considered become queen ants in new colonies. They may to be beneficial insects. But when they choose indoor nesting sites if suitable ones are I invade a home, ants can be a nuisance. not available outdoors. When she finds a nesting To manage an ant infestation in the home, site, the queen loses her wings and begins to lay you must first identify the species. The next step eggs, which hatch into legless, grub-like larvae. is to learn about the biology of that species and The queen feeds the larvae as they develop determine where the colony might be nesting. through several stages, molting and growing Some species commonly nest indoors, while oth- between each stage. Larvae then form pupae and ers nest outside and enter a home just to look for soon emerge as adult ants. Once worker ants food. have developed, the queen no longer needs to To rid your home of ants, you must eliminate care for the brood. the colonies or nests. Some treatments, such When winged ants swarm in the home, it as insecticides sprayed on ant trails, kill only a is likely that their colony is located somewhere few foraging worker ants. They do not eliminate inside. Winged ants swarming outside, such as colonies. In fact, such treatments can sometimes around porch lights, should not be a concern. make the problem worse by causing a colony to To discourage them, turn off porch lights or use split into two or more separate colonies. -

The Impact and Spread of the Invasive Garden Ant: an Alien Invasive Species in the UK Phillip Buckham-Bonnett Phd Thesis Univer

The impact and spread of the invasive garden ant: an alien invasive species in the UK Phillip Buckham-Bonnett PhD Thesis University of York Biology December 2019 Abstract Alongside climate change and habitat loss, invasive non-native species are a major threat to the natural world. Ants are amongst the most widespread and damaging invasive species. The invasive garden ant, Lasius neglectus, has only recently been detected in the United Kingdom and is the country’s first invasive ant species. This thesis aims to assess the impact and spread of this species in the UK. In this thesis I carry out a UK-wide risk assessment for the species and develop a protocol for experimentally assessing its potential impact on an economically important crop plant. I investigate behaviours that may contribute to its success as an invasive species. I evaluate the feasibility of commonly used pesticides for the control of Lasius neglectus, and conclude that granular products, while convenient for large- scale application, are not suitable for this species due to low palatability; this may hinder future control attempts. I carry out a large-scale survey to assess the distribution of this easily-overlooked species, and conclude that while it is not as widely distributed in botanic gardens as expected, the number of urban sites where it occurs is increasing rapidly. In conclusion Lasius neglectus is difficult to detect and hard to eradicate once established, so efforts should be made to reduce its spread from the areas in which it currently occurs. 2 Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................. 2 Contents ............................................................................................................ 3 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................... 4 Declaration ....................................................................................................... -

The Use of Canine Scent Detection, Tracking Tubes, Dynamic Occupancy Modeling and Genetic Analysis of Scat to Better Understand

2/24/2015 PPM The Use of Canine Scent Detection, • Heteromyid (6g) • External cheek pouches Tracking Tubes, • Subspecies of Perognathus longimembris Dynamic Occupancy Modeling and • Critically Endangered • 4 extant populations (3 on Camp Pendleton) Genetic Analysis of Scat to Better Understand and Inform Habitat • West facing gentle slopes w/in 4 km of ocean Recovery of the Pacific Pocket • Sandy Substrates Mouse • Open CSS with forbs and grasses U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey PPM Distribution Historic & Current Behavior • Nonsocial, nocturnal • Dust Bath, Cache seeds • Torpor in Summer to Winter (related to seed availability?) • Temporal Activity Variable by sex/age • Forage primarily on seeds (forbs, grasses, shrubs) • Reproduction- 1-2 litters (gestate 2 weeks, wean 30 days) • Home Range estimates (.017 ha- 0.25 ha) U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Program History Acknowledgements 2007- Monitoring Workshop with Scientific Panel MCB Camp Pendleton Sherri Sullivan, Roland Sosa, Eric Kirshner, Kaye London Set Program Goals USGS Scientific Panel 2008- Live-Trap North & South San Mateo . Robert Fisher Ken Burnham, Peter Meserve, Mark 2009- Sample Methodology Study . Tritia Matsuda Pavelka, Will Miller, Doug Deutsman 2010- PPM Discovery Effort . Denise Clark . Conservation Canines (UW) . Jeremy Sebes Heath Smith, Julie Ubigau, Sam Wasser, 2011- Creation of Monitoring Plan . Laura Fox Rebecca Booth, Michelle , Samson, Allie, 2012- Monitor Year 1 . Melanie Burlaza Casey, Timmy . Devin Adsit-Morris . SDZoo: 2013- Monitor Year 2 + Argentine Ant Sampling . Jeff Tracey Debra Shier, Amaranta Kozuch 2014- Monitor Year 3 + Genetic Barcode Assay . -

The Birth of Ant Genomics

COMMENTARY The birth of ant genomics Raghavendra Gadagkar1 Centre for Ecological Sciences and Centre for Contemporary Studies, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560 012, India; and Evolutionary and Organismal Biology Unit, Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research, Bangalore 560 064, India oday science is in the age of bi- social organization (11), mechanisms of ology and biology is in the age of caste determination (12), and the organi- T genomics. Sequencing the entire zation of labor (13). The fire ant S. invicta, genome of an organism, an en- introduced from South America, has terprise that could not have been imagined spread across the United States and has barely 50 y ago, is being thought of as the become one of the most serious pests first step toward a complete understand- threatening agriculture and human life ing of its biology. If I had been asked to and defying most extermination efforts recommend just two families of living (14). C. floridanus, found in the south- organisms from which to pick the first two eastern United States, is perhaps the most species for whole-genome sequencing, I nondescript of the lot but it is good to would surely have suggested Hominidae have to compare with the others, especially (with ourselves) and Formicidae (with all because of its well organized, monogy- ants). My choice of the ant family is easy nous colonies with only two worker castes to justify. The family Formicidae consists (15). H. saltator is rather special, a jumping of approximately 14,000 species of ants, ant from India whose workers can copu- all of which exhibit advanced and sophis- late with males from their own colonies ticated social life, not unlike our own in and contribute to egg-laying, alongside many respects and perhaps surpassing us the queens, as gamergates (i.e., married in some ways.