20 Impact of Environmental Obesogens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

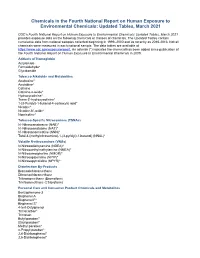

Chemicals in the Fourth Report and Updated Tables Pdf Icon[PDF

Chemicals in the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Updated Tables, March 2021 CDC’s Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals: Updated Tables, March 2021 provides exposure data on the following chemicals or classes of chemicals. The Updated Tables contain cumulative data from national samples collected beginning in 1999–2000 and as recently as 2015-2016. Not all chemicals were measured in each national sample. The data tables are available at https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport. An asterisk (*) indicates the chemical has been added since publication of the Fourth National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals in 2009. Adducts of Hemoglobin Acrylamide Formaldehyde* Glycidamide Tobacco Alkaloids and Metabolites Anabasine* Anatabine* Cotinine Cotinine-n-oxide* Hydroxycotinine* Trans-3’-hydroxycotinine* 1-(3-Pyridyl)-1-butanol-4-carboxylic acid* Nicotine* Nicotine-N’-oxide* Nornicotine* Tobacco-Specific Nitrosamines (TSNAs) N’-Nitrosoanabasine (NAB)* N’-Nitrosoanatabine (NAT)* N’-Nitrosonornicotine (NNN)* Total 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol) (NNAL)* Volatile N-nitrosamines (VNAs) N-Nitrosodiethylamine (NDEA)* N-Nitrosoethylmethylamine (NMEA)* N-Nitrosomorpholine (NMOR)* N-Nitrosopiperidine (NPIP)* N-Nitrosopyrrolidine (NPYR)* Disinfection By-Products Bromodichloromethane Dibromochloromethane Tribromomethane (Bromoform) Trichloromethane (Chloroform) Personal Care and Consumer Product Chemicals and Metabolites Benzophenone-3 Bisphenol A Bisphenol F* Bisphenol -

The Obesogen Hypothesis: Current Status and Implications for Human Health

Curr Envir Health Rpt (2014) 1:333–340 DOI 10.1007/s40572-014-0026-8 MECHANISMS OF TOXICITY (CJ MATTINGLY, SECTION EDITOR) The Obesogen Hypothesis: Current Status and Implications for Human Health Jerrold J. Heindel & Thaddeus T. Schug Published online: 20 September 2014 # Springer International Publishing AG (outside the USA) 2014 Abstract Obesity and diabetes have overtaken smoking as agreed upon that this obesity epidemic is the product of poor the number 1 preventable health determinate in the United nutrition and lack of exercise. However, obesity is a complex States. In its basic form, obesity is due to disruptions of the endocrine disease caused by disruption of many control sys- endocrine systems that control food intake, satiety, and meta- tems involving interaction between genetic and environmental bolic rate. Recent studies have identified a subclass of endo- cues such as nutrition, exercise, drugs, behavior, alterations in crine disrupting chemicals that interfere with hormonally reg- the microbiome, and exposure to environmental chemicals. ulated metabolic processes, especially during early develop- Genome wide association studies using large populations ment. These chemicals, called “obesogens,” may predispose have uncovered some 40 novel single nucleotide polymor- individuals to gain weight despite efforts to limit caloric intake phisms that are associated with increased body mass index and increase physical activity. Evidence suggests that chemi- (BMI), but together these genetic identifiers account for less cal exposures early in life can predispose individuals to weight than 5 % of the incidence of obesity [2]. Indeed, there are no gain through programming changes, which may enhance dys- known genetic mechanisms that can explain the remarkable functional eating behaviors later in life. -

Pfoa) Or Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (Pfos

National Toxicology Program NTP U.S. Department of Health and Human Services NTP Monograph Immunotoxicity Associated with Exposure to Perfluorooctanoic Acid or Perfluorooctane Sulfonate September 2016 NTP MONOGRAPH ON IMMUNOTOXICITY ASSOCIATED WITH EXPOSURE TO PERFLUOROOCTANOIC ACID (PFOA) OR PERFLUOROOCTANE SULFONATE (PFOS) September, 2016 Office of Health Assessment and Translation Division of the National Toxicology Program National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences National Institutes of Health U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Systematic Review of Immunotoxicity Associated with Exposure to PFOA or PFOS TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................................II List of Table and Figures ................................................................................................................... IV Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Peer Review Of The Draft NTP Monograph ......................................................................................... 2 Peer-Review Panel .............................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Objective and Specific Aims ............................................................................................................... -

PFAS MCL Technical Support Document

ATTACHMENT 1 New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Technical Background Report for the June 2019 Proposed Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) and Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQSs) for Perfluorooctane sulfonic Acid (PFOS), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorononanoic Acid (PFNA), and Perfluorohexane sulfonic Acid (PFHxS) And Letter from Dr. Stephen M. Roberts, Ph.D. dated 6/25/2019 – Findings of Peer Review Conducted on Technical Background Report June 28, 2019 New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Technical Background Report for the June 2019 Proposed Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) and Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQSs) for Perfluorooctane sulfonic Acid (PFOS), Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), Perfluorononanoic Acid (PFNA), and Perfluorohexane sulfonic Acid (PFHxS) June 28, 2019 Table of Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... iii Section I. Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 1 Section II. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 2 Section III. Reference Dose Derivation ........................................................................................................ -

Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA)

United States Office of Water EPA 822-R-16-003 Environmental Protection Mail Code 4304T May 2016 Agency Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Perfluorooctanoic Acid – May 2016 i Health Effects Support Document for Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Water (4304T) Health and Ecological Criteria Division Washington, DC 20460 EPA Document Number: 822-R-16-003 May 2016 Perfluorooctanoic Acid – May 2016 ii BACKGROUND The Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), as amended in 1996, requires the Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to periodically publish a list of unregulated chemical contaminants known or anticipated to occur in public water systems and that may require regulation under SDWA. The SDWA also requires the Agency to make regulatory determinations on at least five contaminants on the Contaminant Candidate List (CCL) every 5 years. For each contaminant on the CCL, before EPA makes a regulatory determination, the Agency needs to obtain sufficient data to conduct analyses on the extent to which the contaminant occurs and the risk it poses to populations via drinking water. Ultimately, this information will assist the Agency in determining the most appropriate course of action in relation to the contaminant (e.g., developing a regulation to control it in drinking water, developing guidance, or deciding not to regulate it). The PFOA health assessment was initiated by the Office of Water, Office of Science and Technology in 2009. The draft Health Effects Support Document for Perfluoroctanoic Acid (PFOA) was completed in 2013 and released for public comment in February 2014. -

Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) November 2017 TECHNICAL FACT SHEET – PFOS and PFOA

Technical Fact Sheet – Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) November 2017 TECHNICAL FACT SHEET – PFOS and PFOA Introduction At a Glance This fact sheet, developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Manmade chemicals not (EPA) Federal Facilities Restoration and Reuse Office (FFRRO), provides a naturally found in the summary of two contaminants of emerging concern, perfluorooctane environment. sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), including physical and Fluorinated compounds that chemical properties; environmental and health impacts; existing federal and repel oil and water. state guidelines; detection and treatment methods; and additional sources of information. This fact sheet is intended for use by site managers who may Used in a variety of industrial address these chemicals at cleanup sites or in drinking water supplies and and consumer products, such for those in a position to consider whether these chemicals should be added as carpet and clothing to the analytical suite for site investigations. treatments and firefighting foams. PFOS and PFOA are part of a larger group of chemicals called per- and Extremely persistent in the polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs). PFASs, which are highly fluorinated environment. aliphatic molecules, have been released to the environment through Known to bioaccumulate in industrial manufacturing and through use and disposal of PFAS-containing humans and wildlife. products (Liu and Mejia Avendano 2013). PFOS and PFOA are the most Readily absorbed after oral widely studied of the PFAS chemicals. PFOS and PFOA are persistent in the exposure. Accumulate environment and resistant to typical environmental degradation processes. primarily in the blood serum, As a result, they are widely distributed across all trophic levels and are found kidney and liver. -

Microbiota and Obesogens: Environmental Regulators of Fat Storage

Microbiota and obesogens: environmental regulators of fat storage John F. Rawls, Ph.D. Department of Molecular Genetics & Microbiology Center for Genomics of Microbial Systems Duke University School of Medicine Seminar outline 1. Introduction to the microbiota 2. Microbiota as environmental factors in obesity 3. Obesogens as environmental factors in obesity Seeing and understanding the unseen Antonie van Leewenhoek 1620’s: Described differences between microbes associated with teeth & feces during health & disease. Louis Pasteur 1850’s: Helps establish the “germ theory” of disease. 1885: Predicts that germ-free animals can not survive without “common microorganisms”. Culture-independent analysis of bacterial communities using 16S rRNA gene sequencing 16S rRNA 16S SSU rRNA 16S rRNA gene V1 V2 V3 V4 V5 V6 V7 V8 V9 Culture-independent analysis of bacterial communities using 16S rRNA gene sequencing plantbiology.siu.edu Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA genes revealed 3 domains and a vast unappreciated diversity of microbial life You are here Carl Woese Glossary • Microbiota / microflora: the microorganisms of a particular site, habitat, or period of time. • Microbiome: the collective genomes of the microorganisms within a microbiota. • Germ-free / axenic: of a culture that is free from living organisms other than the host species. • Gnotobiotic: of an environment for rearing organisms in which all the microorganisms are either excluded or known. Current techniques for microbiome profiling Microbial community Morgan et al. (2012) Trends in -

Chemicals and Obesity

CHEMICALS AND OBESITY While diet and exercise are important factors in the obesity epidemic, an emerging body of science demonstrates that exposures to chemical obesogens may be important contributors. A number of chemicals known to disrupt hormones also appear to affect the size and number of fat cells or hormones that regulate appetite and metabolism. The U.S. is confronting the growing rate of obesity as a major building materials. Hundreds of chemicals are recognized as public health problem. One-third of American children, and hormone disrupters that impact the delicate hormone balance two-thirds of adults, are obese or overweight.1 The direct costs in the human body. Hormone disrupters are especially harmful of treating obesity alone are $190 billion per year,2 which might because, like hormones themselves, they can exert health be as high as 16.5 percent of national health care spending.3 impacts even at minute levels of exposure and exposures in the While diet and exercise are widely recognized as important womb can have lifelong impacts. factors in the obesity epidemic, there is an emerging body of science showing that exposures to chemical obesogens may be important contributors. Obesogens are chemical agents Hormone disruption that promote fat accumulation and alter feeding behaviors A number of chemicals known to disrupt hormones also appear through various mechanisms, and we are all exposed to them to be obesogens.4,5 A 2011 National Institute of Environmental every day. Health Sciences (NIEHS) expert workshop concluded that the scientific literature supports a link between certain environ- mental chemicals and increased risk for obesity as well as Type 2 diabetes.6 Chemicals can affect the size and number of fat Widespread exposure cells or the hormones that regulate appetite and metabolism. -

Perfluorooctanoic Acid (Pfoa) and Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid (Pfos)

WATER QUALITY FACT SHEET: PERFLUOROOCTANOIC ACID (PFOA) AND PERFLUOROOCTANESULFONIC ACID (PFOS) Chemical Properties: • PFOA and PFOS are fluorinated organic chemicals that are part of a larger man-made chemical group referred to as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which are resistant to heat, water, and oil. • The chemicals have been used in consumer products such as carpets, clothing, fabrics for furniture, paper packaging for food, and other materials (e.g., cookware) designed to be waterproof, stain- resistant or non-stick. • They also have been used in fire-retarding foam at airfields, military bases, and various industrial processes. • PFOA and PFOS have been the most extensively produced and studied PFAS. PFAS also includes GenX chemicals and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS) which require further study. • PFAS tends to accumulate in groundwater with contamination typically localized and associated with facilities where the chemicals were produced or used to manufacture other products. Health Concerns: • In 2016, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) issued a lifetime health advisory for PFOA and PFOS for drinking water. Municipalities were advised that they should notify their customers of the presence of levels over 70 ppt (0.07 µg/L) in community water supplies. • Studies indicate that PFOA and PFOS may result in adverse health effects including developmental effects to fetuses during pregnancy or breastfed infants, cancer, liver effects, immune effects, thyroid effects, and cholesterol changes. Regulatory Considerations: • The USEPA has not regulated PFOA and PFOS. There is no Federal MCL or MCLG. • In August 2019, the California State Water Resources Control Board Division of Drinking Water (DDW) updated notification levels for PFOA and PFOS from 14 ppt to 5.1 ppt for PFOA and from 13 ppt to 6.5 ppt for PFOS. -

Perfluorooctanoic Acid Levels, Nuclear Receptor Gene Polymorphisms, And

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Associations among perfuorooctanesulfonic/ perfuorooctanoic acid levels, nuclear receptor gene polymorphisms, and lipid levels in pregnant women in the Hokkaido study Sumitaka Kobayashi1, Fumihiro Sata1,2, Houman Goudarzi1,3, Atsuko Araki1, Chihiro Miyashita1, Seiko Sasaki4, Emiko Okada5, Yusuke Iwasaki6, Tamie Nakajima7 & Reiko Kishi1* The efect of interactions between perfuorooctanesulfonic (PFOS)/perfuorooctanoic acid (PFOA) levels and nuclear receptor genotypes on fatty acid (FA) levels, including those of triglycerides, is not clear understood. Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to analyse the association of PFOS/PFOA levels and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in nuclear receptors with FA levels in pregnant women. We analysed 504 mothers in a birth cohort between 2002 and 2005 in Japan. Serum PFOS/ PFOA and FA levels were measured using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Maternal genotypes in PPARA (rs1800234; rs135561), PPARG (rs3856806), PPARGC1A (rs2970847; rs8192678), PPARD (rs1053049; rs2267668), CAR (rs2307424; rs2501873), LXRA (rs2279238) and LXRB (rs1405655; rs2303044; rs4802703) were analysed. When gene-environment interaction was considered, PFOS exposure (log10 scale) decreased palmitic, palmitoleic, and oleic acid levels (log10 scale), with the observed β in the range of − 0.452 to − 0.244; PPARGC1A (rs8192678) and PPARD (rs1053049; rs2267668) genotypes decreased triglyceride, palmitic, palmitoleic, and oleic acid levels, with the observed β in the range of − 0.266 to − 0.176. Interactions between PFOS exposure and SNPs were signifcant for palmitic acid (Pint = 0.004 to 0.017). In conclusion, the interactions between maternal PFOS levels and PPARGC1A or PPARD may modify maternal FA levels. Te genetic makeup of a person and the environmental factors might be responsible for regulating the levels of serum lipids, such as fatty acids (FA) and triglycerides (TG)1. -

Environmental Factors, Epigenetics, and Developmental Origin of Reproductive Disorders

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Reprod Manuscript Author Toxicol. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 March 01. Published in final edited form as: Reprod Toxicol. 2017 March ; 68: 85–104. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.07.011. Environmental Factors, Epigenetics, and Developmental Origin of Reproductive Disorders Shuk-Mei Hoa,b,c,d,*, Ana Cheonga,b, Margaret A. Adgente, Jennifer Veeversa,c, Alisa A. Suenf,g, Neville N.C. Tama,b,c, Yuet-Kin Leunga,b,c, Wendy N. Jeffersonf, and Carmen J. Williamsf,* aDepartment of Environmental Health, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America bCenter for Environmental Genetics, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America cCincinnati Cancer Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America dCincinnati Veteran Affairs Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, United States of America eDepartment of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, United States of America fReproductive Medicine Group, Reproductive & Developmental Biology Laboratory, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, United States of America gCurriculum in Toxicology, UNC Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States of America Abstract Sex-specific differentiation, development, and function of the reproductive system are largely dependent on steroid hormones. For this reason, developmental exposure -

3/4/13 Dear Children's Committee Public Hearing, As a Lifelong Resident of Connecticut and a Nurse with a Master in Public

3/4/13 Dear Children’s Committee Public Hearing, As a lifelong resident of Connecticut and a Nurse with a Master in Public Health, I am in strong support of S.B. No. 981 AN ACT CONCERNING PESTICIDES ON SCHOOL GROUNDS. Over my past 23 years as a nurse it has been overwhelming to see the growing amount of chronic degenerative disease. Why as a society are we so sick? What I believe we are sorely missing is prevention. The dictionary defines prevention simply as: The action of stopping something from happening or arising. This bill is a preventative action towards supporting adolescent environmental health. The American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement “Pesticide Exposure in Children” is asking for governmental support to improve safety and reduction in childhood exposure. (Pediatrics: Pesticide Exposure in Children. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2012/11/21/peds.2012- 2757.full.pdf+html ) Here are highlights of some of the science and studies I’d like to share: “Of the 30 most commonly used lawn pesticides, 19 can cause cancer, 13 are linked to birth defects, 21 can affect reproduction and 15 are nervous system toxicants. The most popular and widely used lawn chemical, 2,4-D, which kills broad leaf weeds like dandelions, is an endocrine disruptor with predicted human health hazards ranging from changes in estrogen and testosterone levels, thyroid problems, prostate cancer and reproductive abnormalities. 2,4-D has also been linked to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Other lawn chemicals, like glyphosate (Roundup), have also been linked to serious adverse chronic effects in humans.” (Pesticides and You, pg 10, http://www.beyondpesticides.org/schools/index.php) “So much new science exists around the links between obesity and environmental contaminants that a new term, “obesogen” (like carcinogen) has emerged in the literature.