Uncovering Common Bacterial Skin Infections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2020 Goal the Goal of the Residency Program Is to Develop Future Leaders in Both Research and Clinical Medicine

Residency Training Program July 2020 Goal The goal of the Residency Program is to develop future leaders in both research and clinical medicine. Flexibility within the program allows for the acquisition of fundamental working knowledge in all subspecialties of dermatology. All residents are taught a scholarly approach to patient care, aimed at integrating clinicopathologic observation with an understanding of the basic pathophysiologic processes of normal and abnormal skin. Penn’s Residency Program consists of conferences, seminars, clinical rotations, research, and an opportunity to participate in the teaching of medical students. An extensive introduction into the department and the William D. James, M.D. Director of Residency Program clinic/patient care service is given to first-year residents. A distinguished clinical faculty and research faculty, coupled with the clinical and laboratory facilities, provides residents with comprehensive training. An appreciation of and participation in the investigative process is an integral part of our residency. Graduates frequently earn clinical or basic science fellowship appointments at universities across the country. Examples of these include: pediatric dermatology, dermatopathology, dermatologic surgery, dermatoepidemiology, postdoctoral and Clinical Educator fellowships. Additional post graduate training has occurred at the NIH and CDC. Graduates of our program populate the faculty at Harvard, Penn, Johns Hopkins, MD Anderson, Dartmouth, Penn State, Washington University, and the Universities of Washington, Pittsburgh, Vermont, South Carolina, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, and the University of California San Francisco. Additionally, some enter private practice to become pillars of community medicine. Misha A. Rosenbach, M.D. Associate Director of Residency Program History The first medical school in America, founded in 1765, was named the College of Philadelphia. -

Fungal Infections from Human and Animal Contact

Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 4 4-25-2017 Fungal Infections From Human and Animal Contact Dennis J. Baumgardner Follow this and additional works at: https://aurora.org/jpcrr Part of the Bacterial Infections and Mycoses Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, and the Skin and Connective Tissue Diseases Commons Recommended Citation Baumgardner DJ. Fungal infections from human and animal contact. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2017;4:78-89. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1418 Published quarterly by Midwest-based health system Advocate Aurora Health and indexed in PubMed Central, the Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews (JPCRR) is an open access, peer-reviewed medical journal focused on disseminating scholarly works devoted to improving patient-centered care practices, health outcomes, and the patient experience. REVIEW Fungal Infections From Human and Animal Contact Dennis J. Baumgardner, MD Aurora University of Wisconsin Medical Group, Aurora Health Care, Milwaukee, WI; Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI; Center for Urban Population Health, Milwaukee, WI Abstract Fungal infections in humans resulting from human or animal contact are relatively uncommon, but they include a significant proportion of dermatophyte infections. Some of the most commonly encountered diseases of the integument are dermatomycoses. Human or animal contact may be the source of all types of tinea infections, occasional candidal infections, and some other types of superficial or deep fungal infections. This narrative review focuses on the epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of anthropophilic dermatophyte infections primarily found in North America. -

Bacterial Skin Infections an Observational Study

RESEARCH Geoffrey Spurling Deborah Askew David King Geoffrey K Mitchell MBBS, DTM&H, FRACGP, is Senior PhD, is Senior Research Fellow, MBBS, MPH, FRACGP, is Senior Lecturer, MBBS, PhD, FRACGP, FAChPM, Lecturer, Discipline of General Practice, Discipline of General Practice, Discipline of General Practice, University is Associate Professor, Discipline University of Queensland. g.spurling@ University of Queensland. of Queensland. of General Practice, University of uq.edu.au Queensland. Bacterial skin infections An observational study Bacterial skin infections such as impetigo and boils are Background common, contagious, often painful, and have the potential to We aimed to determine the feasibility of measuring resolution rates of recur. They are caused by Staphylococcus aureus and bacterial skin infections in general practice. occasionally by Streptococcus pyogenes, and are transmitted Methods by skin-to-skin contact, fomite contact or contact with nasal Fifteen general practitioners recruited patients from March 2005 to carriers.1 In the United Kingdom, incidence of skin infections October 2007 and collected clinical and sociodemographic data at in children in 2005 was approximately 75 per 100 000.2 Skin baseline. Patients were followed up at 2 and 6 weeks to assess lesion infection rates are likely to be higher in warmer climates. The resolution. only Australian data we found were for one Northern Territory Results Aboriginal Medical Service (Danila Dilba), which recorded 7.5 Of 93 recruited participants, 60 (65%) were followed up at 2 and 6 per 100 consultations for localised skin infections.3 weeks: 50% (30) had boils, 37% (22) had impetigo, 83% (50) were prescribed antibiotics, and active follow up was suggested for 47% Suggested risk factors for impetigo include: household crowding, (28). -

Current Microbiological, Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects of Impetigo Lior Zusmanovich, Lior Charach and Gideon Charach*

ISSN: 2378-3656 Zusmanovich et al. Clin Med Rev Case Rep 2018, 5:205 DOI: 10.23937/2378-3656/1410205 Volume 5 | Issue 3 Clinical Medical Reviews Open Access and Case Reports CASE REPORT Current Microbiological, Clinical and Therapeutic Aspects of Impetigo Lior Zusmanovich, Lior Charach and Gideon Charach* Department of Internal Medicine “C”, Affiliated to Tel Aviv University, Israel *Corresponding author: Gideon Charach, Department of Internal Medicine “C”, Tel Aviv Sourasky Check for Medical Center, Sackler Medical School, Affiliated to Tel Aviv University, 6 Weizman Street, Tel Aviv updates 6423906, Israel, Tel: +972-3-6973766, Fax: +972-3-6973929, E-mail: [email protected] nonpurulent and purulent cellulitis, and treatment is Abstract based on extent of infection and risk factors. Abscesses Impetigo is a highly contagious infection of the epidermis, involve the dermis and deeper skin tissues as a result of seen especially among children, and transmitted through direct contact. Two bacteria are associated with impetigo: pus formation. S. aureus and GAS. Over 140 million people are suffering Impetigo is observed most frequently among chil- from impetigo at each time point, over 100 million are chil- dren. Two forms of impetigo exist, namely impetigo conta- dren 2-5 years of age and is transmitted through direct giosa, known as the non-bullous form and the second one contact [1]. Risk factors for impetigo include poor hy- being bullous impetigo which presents with large and fragile giene, low economic status, crowding and underlying bullae. Treatment options for impetigo include systemic an- scabies [2,3]. Important consideration is carriage of tibiotics, topical antibiotics as well as topical disinfectants. -

Naeglaria and Brain Infections

Can bacteria shrink tumors? Cancer Therapy: The Microbial Approach n this age of advanced injected live Streptococcus medical science and into cancer patients but after I technology, we still the recipients unfortunately continue to hunt for died from subsequent innovative cancer therapies infections, Coley decided to that prove effective and safe. use heat killed bacteria. He Treatments that successfully made a mixture of two heat- eradicate tumors while at the killed bacterial species, By Alan Barajas same time cause as little Streptococcus pyogenes and damage as possible to normal Serratia marcescens. This Alani Barajas is a Research and tissue are the ultimate goal, concoction was termed Development Technician at Hardy but are also not easy to find. “Coley’s toxins.” Bacteria Diagnostics. She earned her bachelor's degree in Microbiology at were either injected into Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo. The use of microorganisms in tumors or into the cancer therapy is not a new bloodstream. During her studies at Cal Poly, much idea but it is currently a of her time was spent as part of the undergraduate research team for the buzzing topic in cancer Cal Poly Dairy Products Technology therapy research. Center studying spore-forming bacteria in dairy products. In the late 1800s, German Currently she is working on new physicians W. Busch and F. chromogenic media formulations for Fehleisen both individually Hardy Diagnostics, both in the observed that certain cancers prepared and powdered forms. began to regress when patients acquired accidental erysipelas (cellulitis) caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. William Coley was the first to use New York surgeon William bacterial injections to treat cancer www.HardyDiagnostics.com patients. -

Cutaneous Manifestations of HIV Infection Carrie L

Chapter Title Cutaneous Manifestations of HIV Infection Carrie L. Kovarik, MD Addy Kekitiinwa, MB, ChB Heidi Schwarzwald, MD, MPH Objectives Table 1. Cutaneous manifestations of HIV 1. Review the most common cutaneous Cause Manifestations manifestations of human immunodeficiency Neoplasia Kaposi sarcoma virus (HIV) infection. Lymphoma 2. Describe the methods of diagnosis and treatment Squamous cell carcinoma for each cutaneous disease. Infectious Herpes zoster Herpes simplex virus infections Superficial fungal infections Key Points Angular cheilitis 1. Cutaneous lesions are often the first Chancroid manifestation of HIV noted by patients and Cryptococcus Histoplasmosis health professionals. Human papillomavirus (verruca vulgaris, 2. Cutaneous lesions occur frequently in both adults verruca plana, condyloma) and children infected with HIV. Impetigo 3. Diagnosis of several mucocutaneous diseases Lymphogranuloma venereum in the setting of HIV will allow appropriate Molluscum contagiosum treatment and prevention of complications. Syphilis Furunculosis 4. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous Folliculitis manifestations can prevent complications and Pyomyositis improve quality of life for HIV-infected persons. Other Pruritic papular eruption Seborrheic dermatitis Overview Drug eruption Vasculitis Many people with human immunodeficiency virus Psoriasis (HIV) infection develop cutaneous lesions. The risk of Hyperpigmentation developing cutaneous manifestations increases with Photodermatitis disease progression. As immunosuppression increases, Atopic Dermatitis patients may develop multiple skin diseases at once, Hair changes atypical-appearing skin lesions, or diseases that are refractory to standard treatment. Skin conditions that have been associated with HIV infection are listed in Clinical staging is useful in the initial assessment of a Table 1. patient, at the time the patient enters into long-term HIV care, and for monitoring a patient’s disease progression. -

Inflammatory Or Infectious Hair Disease? a Case of Scalp Eschar and Neck Lymph Adenopathy After a Tick Bite

Case Report ISSN: 2574 -1241 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2021.35.005688 Adherent Serous Crust of the Scalp: Inflammatory or Infectious Hair Disease? A Case of Scalp Eschar and Neck Lymph Adenopathy after a Tick Bite Starace M1, Vezzoni R*2, Alessandrini A1 and Piraccini BM1 1Dermatology - IRCCS, Policlinico Sant’Orsola, Department of Specialized, Experimental and Diagnostic Medicine, Alma Mater Studiorum, University of Bologna, Italy 2Dermatology Clinic, Maggiore Hospital, University of Trieste, Italy *Corresponding author: Roberta Vezzoni, Dermatology Clinic, Maggiore Hospital, University of Trieste, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: Published: April 17, 2021 The appearance of a crust initially suggests inflammatory scalp diseases, although infectious diseases such as impetigo or insect bites should also be considered among April 27, 2021 the differential diagnoses. We report a case of 40-year-old woman presentedB. Burgdorferi to our, Citation: Starace M, Vezzoni R, Hair Disease Outpatient Service with an adherent serous crust on the scalp and lymphadenopathy of the neck. Serological tests confirmed the aetiology of while rickettsia infection was excluded. Lyme borreliosis can mimic rickettsia infection Alessandrini A, Piraccini BM. Adherent and may present as scalp eschar and neck lymphadenopathy after a tick bite (SENLAT). Serous Crust of the Scalp: Inflammatory Appropriate tests should be included in the diagnostic workup of patients with necrotic or Infectious Hair Disease? A Case of Scalp scalpKeywords: eschar in order to promptly set -

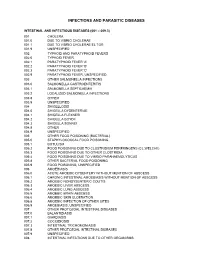

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

Bacterial Infections Diseases Picture Cause Basic Lesion

page: 117 Chapter 6: alphabetical Bacterial infections diseases picture cause basic lesion search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Impetigo page: 118 6.1 Impetigo alphabetical Bullous impetigo Bullae with cloudy contents, often surrounded by an erythematous halo. These bullae rupture easily picture and are rapidly replaced by extensive crusty patches. Bullous impetigo is classically caused by Staphylococcus aureus. cause basic lesion Basic Lesions: Bullae; Crusts Causes: Infection search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Impetigo page: 119 alphabetical Non-bullous impetigo Erythematous patches covered by a yellowish crust. Lesions are most frequently around the mouth. picture Lesions around the nose are very characteristic and require prolonged treatment. ß-Haemolytic streptococcus is cause most frequently found in this type of impetigo. basic lesion Basic Lesions: Erythematous Macule; Crusts Causes: Infection search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Ecthyma page: 120 6.2 Ecthyma alphabetical Slow and gradually deepening ulceration surmounted by a thick crust. The usual site of ecthyma are the legs. After healing there is a permanent scar. The pathogen is picture often a streptococcus. Ecthyma is very common in tropical countries. cause basic lesion Basic Lesions: Crusts; Ulcers Causes: Infection search contents print last screen viewed back next Bacterial infections diseases Folliculitis page: 121 6.3 Folliculitis -

General Dermatology Practice Brochure

Appointments Our Providers David A. Cowan, MD, FAAD We are currently accepting • Fellow, American Academy of Dermatology new patients. • Associate, American College of Call today to schedule your appointment Mohs Micrographic Surgery Monday - Friday, 8:00am to 4:30pm Rebecca G. Pomerantz, MD 1-877-661-3376 • Board Certified, American Academy of Cancellations & “No Show” Policy Dermatology If you are unable to keep your scheduled Lisa L. Ellis, MPAS, PA-C appointment, please call the office and we will • Member, American Academy of Physician be more than happy to reschedule for you. Assistants Failure to notify us at least 48 hours prior to your • Member, PA Society of Physician Assistants Medical and appointment may result in a cancellation fee. • Member, Society of Dermatology Physician Prescription Refills Assistants Surgical Refill requests are handled during normal office Sheri L. Rolewski, MSN, CRNP-BC hours when our staff has full access to medical • National Board Certification, Family Nurse Dermatology records. Refills cannot be called in on holidays, Practitioner Specialty weekends or more than twelve months after your • Member, Dermatology Nurse Association last exam. Please have your pharmacy contact our office directly. Test Results SMy Dermatology Appointment You will be notified when we receive your Date/Day _____________________________________ pathology or other test results, usually within two weeks from the date of your procedure. If you Time _________________________________________ do not hear from us within three -

Dermatology at the Berkeley Outpatient Center

Dermatology Berkeley Outpatient Center Overview Encompassing both medical and cosmetic dermatology, our experts at the Berkeley Outpatient Center offer a full range of diagnostic, treatment and surgical services for patients with cutaneous conditions. Surgical Dermatology • Fellowship-trained expertise in • Close coordination with Plastic Surgery Mohs micrographic surgery for at the Berkeley Outpatient Center, treatment of skin cancers including allowing for streamlined treatment for basal cell carcinomas and squamous related procedures in one location cell carcinomas, as well as treatment of • Outpatient surgery for removal of melanoma in situ with MART-1 staining benign skin growths and skin cancers Medical Dermatology - Conditions Treated/Services Offered • Acne, rosacea and related conditions • Mole/Atypical nevus/Melanoma • Sun-damaged skin surveillance • Aesthetic/Cosmetic dermatology • Non-melanoma skin cancers • Eczema and atopic dermatitis • Pigmentation disorders • HIV/AIDS-related skin conditions • Psoriasis • Lumps under the skin • Rashes • Infections of the skin (bacterial, viral, • Skin checks for patients with fungal and other) concerning lesions • Melanoma • Warts When to see a Dermatologist For more information, please call Dermatology Services at (510) 985-5200. Dermatology Services Providing integrated care in the community. Our Dermatology Team Erin Amerson, MD Drew Saylor, MD, MPH UCSF Health UCSF Health Dermatologist Dermatologic surgeon To learn more about our doctors, visit ucsfhealth.org/find_a_doctor. Office location: Berkeley Outpatient Center 3100 San Pablo Avenue Berkeley, CA 94702 (510) 985-5200 To learn more about our Berkeley Outpatient Center, Adeline St visit johnmuirhealth.com/ September 2020 berkeleyopc..