University Microfilms Litemationa]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3650 Reed Road, Columbus, OH 43220 | P: 614.324.1564 | F: 614.324.1574 | [email protected] Contents

2017–2018 Upper School Course Brochure The Wellington School | 3650 Reed Road, Columbus, OH 43220 | P: 614.324.1564 | F: 614.324.1574 | [email protected] Contents GENERAL INFORMATION p. 3 College Acceptances and Matriculations p. 4 2003-2017 Matriculations p. 6 Course Load p. 6 Adding and Dropping Courses p. 6 Advanced/Honors Courses p. 7 Graduation Requirements p. 8 Course Icons p. 8 Upper School Schedule COURSE DESCRIPTIONS p. 9 Non-Departmental p. 12 English p. 17 History/Social Studies p. 22 Mathematics p. 27 Performing Arts p. 30 Physical Education p. 33 Science p. 39 Visual Arts p. 42 World Languages 2 The Wellington School | 3650 Reed Road, Columbus, OH 43220 | P: 614.324.1564 | F: 614.324.1574 | [email protected] 2017 COLLEGE ACCEPTANCES AND MATRICULATIONS This college list for the Wellington Class of 2017 mirrors and celebrates the diversity found in each student’s talents and interests. Allegheny College Howard University University of Kentucky Amherst College Indiana University University of Maryland Ashland University Iowa State University University of Miami Baldwin-Wallace University Kent State University University of Minnesota Ball State University Loyola University of Chicago University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill Belmont Abbey College Marietta College University of Pennsylvania Belmont University Marquette University University of Pittsburgh Bluffton University Marshall University University of Rhode Island Boston University Mercyhurst University University of Richmond Bowling Green State University -

2011-2012 Annual Report

2012-2013 Annual Report In 2006, a group of committed educational and community leaders participated in--and won--a competition to attract the KIPP network of high performing charter schools to Columbus. In 2008, KIPP Central began enrolling 5th graders and opened its first middle school, KIPP Journey Academy, in the Linden neighborhood. Every student at KIPP Journey Academy had one collective goal: do everything possible to climb the mountain to and through college. With over 90% of them qualifying for free or reduced-price meals, college seemed like an unattainable goal, but they used every moment at KIPP to advance toward college. They read hundreds of books, solved thousands of math problems, and wrote countless essays. After four years of tireless work, KIPP Journey Academy promoted its first class of 8th graders this June. The Class of 2016 took the next step in their journey to and through college and enrolled at some of the top performing high schools in Columbus. Some even received scholarships to prestigious schools like Columbus School for Girls, The Wellington School, and Thomas Worthington High School. With the support of the community, KIPP Central Ohio was able to change the lives of these students. Although this was our first class of 8th graders, it will not be our last. We look forward to helping many more KIPPsters climb the mountain to and through college in the coming years. Judge Algenon L. Marbley Hannah Powell Tuney Chairman of the Board Executive Director KIPP, the Knowledge Is Power Program, is a national network of free, open-enrollment, college-preparatory public charter schools with a track record of preparing students in underserved communities for success in college and in life. -

2020 Fall Sports Media Guide Flipbook

2 3 4 OLENTANGYLIBERTYATHLETICS.COM @LHSATHLETICDEPT WELCOME PATRIOT FANS TO THE 2020 FALL SPORTS SEASON>>> Hello and welcome to another exciting season of Patriot athletics. At Liberty, we are very proud of the tradition and success we’ve established since our beginning in 2003. Over the past 15 years, our student athletes have consistently displayed values surrounding academic, artistic and athletic excellence while conducting themselves as quality young men and women at LIBERTY the same time. 2020 MEDIA GUIDE PRODUCED BY: Extracurriculars are a key component of the educational process. Our GAMEDAY MEDIA expectation is that the “Liberty Way” transcends to the playing fields. In short, CONNECT WITH US: we simply want our students to do things the right way. As adults, we have @GOGAMEDAYMEDIA an opportunity and responsibility to model such behaviors. Sportsmanship and respect must be part of the game. #GAMEDAYFAN Thank you to all of the coaches, parents, district officials and community members FOR SPONSORSHIP INFO PLEASE CONTACT GAMEDAY for your work with our young people and support of Liberty High School. MEDIA BY PHONE OR ONLINE: 503.214.4444 Mike Starner GOGAMEDAYMEDIA.COM Principal Welcome to Olentangy Liberty High School! Participation in interscholastic athletic programs is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Through this participation, our student-athletes will develop life skills that will assist them in achieving success well beyond their playing days. At Olentangy Liberty High School we strive to foster a sense of community through our athletic programs. We sincerely appreciate your support of our young people and encourage you to enjoy this experience with them. -

Web Stats Report: January

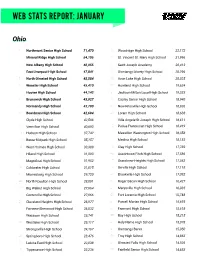

WEB STATS REPORT: JANUARY Ohio 1 Northmont Senior High School 71,470 31 Woodridge High School 22,172 2 Mineral Ridge High School 54,105 32 St. Vincent-St. Mary High School 21,996 3 New Albany High School 48,955 33 Saint Joseph Academy 20,413 4 East Liverpool High School 47,841 34 Olentangy Liberty High School 20,296 5 North Olmsted High School 45,584 35 Avon Lake High School 20,025 6 Wooster High School 45,410 36 Howland High School 19,634 7 Hoover High School 44,142 37 Jackson-Milton Local High School 19,333 8 Brunswick High School 43,927 38 Copley Senior High School 18,940 9 Normandy High School 43,780 39 New Knoxville High School 18,936 10 Boardman High School 42,694 40 Lorain High School 18,638 11 Clyde High School 42,506 41 Villa Angela-St Joseph High School 18,611 12 Vermilion High School 40,693 42 Padua Franciscan High School 18,419 13 Hudson High School 37,742 43 Massillon Washington High School 18,358 14 Berea-Midpark High School 35,157 44 Medina High School 18,183 15 West Holmes High School 33,389 45 Clay High School 17,782 16 Hiland High School 31,993 46 Austintown Fitch High School 17,586 17 Magnificat High School 31,952 47 Grandview Heights High School 17,562 18 Coldwater High School 31,815 48 Orrville High School 17,118 19 Miamisburg High School 29,720 49 Brookville High School 17,092 20 North Royalton High School 28,001 50 Roger Bacon High School 16,427 21 Big Walnut High School 27,664 51 Marysville High School 16,035 22 Centerville High School 27,066 52 Fort Loramie High School 15,748 23 Cleveland Heights High School 26,977 -

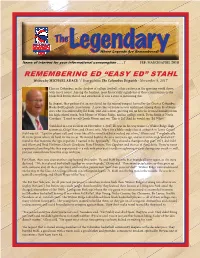

“EASY ED” STAHL Written by MICHAEL ARACE / Exerpt from the Columbus Dispatch - November 9, 2017

TheThe LegendaryLegendaryWhere Legends Are Remembered! Items of interest for your informational consumption . ! FEB./MARCH/APRIL 2018 REMEMBERING ED “EASY ED” STAHL Written by MICHAEL ARACE / Exerpt from The Columbus Dispatch - November 9, 2017 Here in Columbus, in the shadow of college football, other enclaves in the sporting world thrive with lesser notice. Among the hardiest, most historically significant of these communities is the basketball brotherhood, and sisterhood. It is in a state of mourning this. In August, they gathered at an area hotel for the annual banquet hosted by the Greater Columbus Basketball Legends Association. A new class of honorees was enshrined, among them Fred Saun- ders who was followed by Ed Stahl, who did a short, piercing riff on how he learned humility from his high school coach, Jack Moore at Walnut Ridge, and his college coach, Dean Smith at North Carolina. “I used to call Coach Moore and say, ‘This is Ed.’ And he would say, ‘Ed Who?’” Stahl died in a car accident on November 4, 2017. He was on his way to meet a Walnut Ridge High teammate, Greg Olson, and Olson’s wife, Mary, for a bible-study class at a church in Lewis Center. Stahl was 64. “I got the phone call, and it was like all the wind had been sucked out of me,” Olson said. “I’m physically ill, to the point where it’s hard for me to eat. He moved back to the area two years ago, and we reconnected, and what I found in that man was the type of person I wanted to be. -

Name Grade Team/School USCF ID 1 Abubakr, Mohammad 10 Rocky

Oho Grade Level Championships Saturday, November 18, 2017 Entries received as of 11-17-17, 2pm Email any needed corrections to [email protected] Name Grade Team/School USCF ID 1 Abubakr, Mohammad 10 Rocky River High School 16155183 2 Adury, Abhay 9 Revere High School, Richfield 15222132 3 Adury, Anant 5 Bath Elementary School, Bath 15274812 4 Agarwal, Divyang 2 Fort Meigs Elementary School 16251427 Ahmed, Sabreen Withdrawn Gahanna Lincoln High School none 5 Akbar, Izzaz 9 Centennial High School 16454994 6 Al-Askari, Abdel 12 Centennial High School 16458631 7 Albers, Eric 7 The Wellington School 14979200 8 Aleti, Rachit 5 Oak Creek Elementary Schol ** Need ** 9 Allouche, Hamza 12 Centennial High School 16127168 10 Anand, Srihan 8 Solon Middle School 16145447 11 Andey, Aarush 1 Glenoak elementary 16513525 12 Andreini, Jacob 7 University School 14785228 13 Annamreddi, Chaitanya 10 Revere High School 15289815 14 Anthuvan, John 6 St. Joseph Montessori School, Columbus,14727225 Ohio 15 Atekoja, Adenola 10 The Wellington School 16504282 16 Augenstein, Jaden 10 Centennial High School 16511121 17 Ayyagari, Sankalp 5 Mason Intermediate School 15419087 18 Ayygari, Ruthvik 8 Mason Middle School 14897372 19 Babu, Arya 5 Hathaway Brown 16101322 20 Bachman, Aaron 8 Lawrence School 14771302 21 Backus, Christopher K Discovery Montessori 16513436 22 Bagley, Hemma Svasti 8 The Lippman School 15282566 23 Bagley, Saadhika Lakshmi 2 Discovery Montessori School 15827114 24 Baker, Vincent 9 Mount Vernon High School 14304661 25 Balyan, Aryan 8 New Albany Plain Local Schools 15273590 26 Banks, Savannah 7 Anthony Wayne Junior High School 16143215 27 Beasley, London K Discovery Montessori 16513510 28 Berman, Joshua 2 St. -

Olentangy Liberty High School 3584 Home Rd

Olentangy Liberty High School 3584 Home Rd. Darin Meeker Powell All Events Athletic Director OH 43065 04/19/2021 - 04/25/2021 (740) 657-4210 Monday, April 19th Time Team H/A Opponent/Title Site Depart Status Type Upper Arlington High Thompson Park Baseball 5:00 PM Baseball Boys Freshman A Normal League School Diamond #2 Upper Arlington High 5:00 PM Baseball Boys JV A Tremont fields Baseball Diamond Normal League School Upper Arlington High Olentangy Liberty High School 5:00 PM Baseball Boys Varsity H Normal League School Baseball Varsity Field Upper Arlington High 5:15 PM Softball Girls JV A Northam Park Diamond #1 Normal League School Upper Arlington High 5:15 PM Softball Girls Varsity A Tremont fields Softball Diamond Normal League School B Game (New Albany New Albany High School NAHS 5:30 PM Lacrosse Boys JV JVA A Normal League High School) Eagle Stadium Pickerington High Pickerington HS Central Tennis 4:30 PM Tennis Boys Varsity A Normal Non-League School Central Courts Pickerington High Pickerington HS Central JV Tennis 4:30 PM Tennis Boys JV A Normal Non-League School Central Courts Tuesday, April 20th Time Team H/A Opponent/Title Site Depart Status Type Upper Arlington High Upper Arlington High School 7:00 PM Lacrosse Boys Varsity A Normal League School Stadium Upper Arlington High Upper Arlington High School 5:30 PM Lacrosse Boys JV JVA A Normal League School Stadium Hilliard Bradley High Olentangy Liberty High School 4:00 PM Tennis Boys Varsity H Normal League School Tennis Courts #1-4 Senior Night Track - Outdoor Boys Olentangy -

August 10 Wellington.Org/Summer the WELLINGTON SCHOOL 2018 SUMMER PROGRAM

ACADEMICS • ATHLETICS • EARLY CHILDHOOD HIGH SCHOOL • PERFORMANCE & FINE ARTS • STEM June 4 – August 10 wellington.org/summer THE WELLINGTON SCHOOL 2018 SUMMER PROGRAM June 4 – August 10, 2018 Summer Program Weeks WEEK 1: June 4-8 Phil Gross, Director of Summer Program Julie Lovett, Assistant Director of Summer Program WEEK 2: June 11-15 CONTACT INFORMATION 3650 Reed Road Columbus, OH 43220 WEEK 3: June 18-22 Summer Office Phone: 614-324-8882 Email: [email protected] WEEK 4: June 25-29 AGE GROUPS Open to students in prekindergarten (must be age 4) WEEK 5: July 2-6 through grade 12. Register for programs according *No class on July 4 to the grade your child will enter in fall 2018. WEEK 6: July 9-13 CAMP HOURS Morning Program: 9 a.m.-12:00 p.m. Lunch: 12-12:30 p.m. WEEK 7: July 16-20 Afternoon Program: 12:30-3:30 p.m. WEEK 8: July 23-27 EXTENDED DAY HOURS Before Care: 7:30-9 a.m. After Care: 3:30-6 p.m. WEEK 9: July 30-August 3 REGISTER ONLINE WEEK 10: August 6-10 wellington.org/summer 2 | wellington.org/summer THE WELLINGTON SCHOOL 2018 SUMMER PROGRAM WEEK 1: June 4-8 WEEK 2: June 11-15 WEEK 3: June 18-22 Information WEEK 4: June 25-29 PROGRAM OVERVIEW REGISTRATION/CONFIRMATION CANCELLATION/REFUND POLICY • The Wellington Summer Program is open • After registering online, you will receive Due to the necessity for a minimum number WEEK 5: July 2-6 to all families in the community and a confirmation email immediately. -

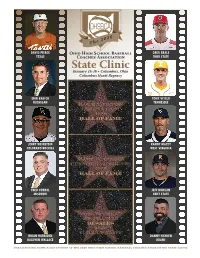

State Clinic, Ohio State University January 16Th, 17Th and 18Th of 2020

2 0 2 0 T h e DAVID PIERCE GREG BEALS TEXAS O H S B OHIO STATE C A StateJanuary 16-18 •Clinic Columbus, Ohio Columbus Hyatt Regency ERIK BAKICH TONY VITELO MICHIGAN TENNESSEE RAY HAMILTON LAKOTA EAST 2020 HALL OF FAME JERRY WEINSTEIN RANDY MAZEY COLORADO ROCKIES WEST VIRGINIA MARC LOWTHER CUYAHOGA HEIGHTS 2020 HALL OF FAME FRED CORRAL JEFF DUNCAN MISSOURI KENT STATE TOM NEUBERT ST. FRANCIS DESALES 2020 HALL OF FAME BRIAN HARRISON DANNY HAYDEN BALDWIN WALLACE MIAMI OFFICIAL BASEBALL OF THE Ohio High School Baseball Coaches Association Dear OHSBCA Members, • Dean Hansen – Th e Welcome to the 69th annual OHSBCA State Clinic, Ohio State University January 16th, 17th and 18th of 2020. You are a • Jordon Banfi eld – member of the 2nd largest coaches associations in University of Akron the United States. Many high school coaches and • Mike Grady – Grady college speakers have said that this is one of the best Pitching School clinics in the nation. I am hoping that you are able to • Eric Smith – take something from this year’s clinic and go back to Youngstown State your school to make the young men in your program University better this coming year and for future players as well. • Erik Bakich – JOHN BAKALAR With my involvement on this board for the University of Michigan past 5 years, I have seen the giant steps forward the • Randy Mazey – West Virginia University association has made. It is my honor to give back as • Fred Corral – University of Missouri Director of the 2020 State Clinic. Th is venue at the • Justin Toole – Cleveland Indians Hyatt Regency and Columbus Convention Center is • Jeff Duncan – Kent State University just one example of what a fi rst class operation we all • Brian Harrison – Baldwin Wallace University are here to witness. -

High School Report

2014 Status of Ohio Graduates Remediation Report by High School Prepared by November 2015 Remediation of Ohio High School Graduates Going Directly to a University System of Ohio College High School Graduates in 2014 Enrolling as First-Time College Students in Fall 2014 Results by High School of Graduation Note: For confidentiality purposes, results are omitted in cases where the value of the denominator is less than 6. Number of First- % of Entering Time Students Enrolling % of Entering College in a Public Students % of Entering % of Entering % of Entering % of Entering Students University or Enrolling in a Students Taking Students Taking Students Taking Students Taking at a USO University Community Developmental Developmental Developmental Developmental County High School by County IRN College Regional Campus College Math or English Math English Math and English Grand Total 48,749 74% 26% 32% 28% 13% 10% Adams Manchester High School 000450 18 94% 6% 17% 6% 11% 0% Adams North Adams High School 033944 14 57% 43% 43% 36% 21% 14% Adams Peebles High School 029538 14 64% 36% 7% 7% 0% 0% Adams West Union High School 038893 27 81% 19% 30% 22% 7% 0% All GED 111111 218 17% 83% 64% 59% 23% 19% All Home Schooled 222222 235 46% 54% 34% 30% 10% 6% Allen Allen East High School 000364 22 50% 50% 32% 32% 9% 9% Allen Bath High School 001750 44 80% 20% 18% 18% 2% 2% Allen Bluffton High School 003038 28 64% 36% 29% 21% 14% 7% Allen Elida High School 010199 52 60% 40% 29% 23% 10% 4% Allen Lima Central Catholic 053165 25 72% 28% 44% 40% 8% 4% Allen Lima Senior -

Liberty-2020-Spring-Sports-Media

BASEBALL 7 WELCOME PATRIOTS TO THE 2020 PATRIOTS SPRING SPORTS SEASON SOFTBALL 15 Hello and welcome to another exciting season of Patriot athletics. At Liberty, we are LIBERTY very proud of the tradition and success we’ve established since our beginning in 2020 MEDIA GUIDE BOYS LACROSSE 22 2003. Over the past 15 years, our student athletes have consistently displayed values PRODUCED BY: surrounding academic, artistic and athletic excellence while conducting themselves as GAMEDAY MEDIA quality young men and women at the same time. PHOTOGRAPHY BY: HR IMAGING BOYS VOLLEYBALL 38 DELANEY BROWN Extracurriculars are a key component of the educational process. Our expectation is that the “Liberty Way” transcends to the playing fields. In short, we simply want our students to do things the right way. As adults, we have an opportunity and responsibility to model such behaviors. Sportsmanship and respect must be part of the game. TRACK & FIELD 44 TABLE OF CONTENTS OF TABLE Thank you to all of the coaches, parents, district officials and community members for your work with our young people and support of Liberty High School. TENNIS 54 CONNECT WITH US: @GOGAMEDAYMEDIA Mike Starner #GAMEDAYFAN Mike Starner - Principal FOR SPONSORSHIP INFO PLEASE CONTACT GAMEDAY MEDIA BY PHONE OR ONLINE: 503.214.4444 GOGAMEDAYMEDIA.COM Welcome to Olentangy Liberty High School! Participation in interscholastic athletic programs is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Through this participation, our student-athletes will develop life skills that will assist them in achieving success well beyond their playing days. At Olentangy Liberty High School we strive to foster a sense of community through our athletic programs. -

Yearbook Title) City Years

Ohio Genealogical Society Yearbook Collection *School names underlined in blue are hyperlinked to digital yearbooks of that school on an external site* ` School Name (Yearbook Title) City Years Ada High School (Watchdog) Ada [SR11w] 1940 Ada High School (We) Ada [SR11w] 1941-42, 1963, 1987, 2012-13, 2017 Ohio Northern University Ada [SR3n] 1918, 1920, 1923-32, 1934-38, 1940-42, 1946-51, 1953-57, 1959-64, 1967-69, 1971-85, 1987-97, 2000-02, 2006-08, (Northern) 2011, 2013-14 Adario High School (Hi-Lites) Adario [SR19h] 1933 Fulton Township School Ai [SR959f] 1949, 1955-56, 1960 (Fultonian) Symmes Valley High School Aid [SR65v] 2009-19 (Viking) Archbishop Hoban High School Akron [SR651w] 1957-58, 1961-63, 1966-70, 1980, 1983-84, 1986, 1989-92, 1994-95, 1997, 1999-2012 (Way) Buchtel College (Buchtel) Akron [SR3b] 1908 Buchtel College (Tel-Buch) Akron [SR3t] 1911 Buchtel High School (Griffin) Akron [SR854g] Jun 1940, Jun 1941, Jun 1942, Jun 1943, Jun 1944, Jan 1945, Jun 1945, Jun 1946, Jan 1947, Jun 1947, Jan 1948, Jun 1948, Jan 1949, Jun 1949, Jan 1950, Jun 1950, Jan 1951, Jun 1951, Jan 1952, Jun 1952, Jan 1953, Jun 1953, 1954-69, 1986, 1988-89, 1991-93, 1995-99, 2003, 2015-17 Central High School (Central Akron [SR333c] JUNE 1951 Forge) Central High School (Wildcat) Akron [SR333w] 1958, 1961, 1964-65, 1968-70 Central – Hower (Artisan) Akron [SR333a] 1971-76, 1978-79, 1981-82, 1984, 1988-89, 1993, 1998-99, 2006 East High School (Magic Carpet) Akron [SR77m] 1926 East High School (Caravan) Akron [SR77c] JAN 1928, JUNE 1930 Page 1 Ohio Genealogical