Composition Portfolio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repeat-The-Beat: Industries, Genres and Citizenships in Dance Music Magazines Repeat-The-Beat: Iii

Repeat-The-Beat: Industries, Genres and Citizenships in Dance Music Magazines Christy Elizabeth Newman This dissertation is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in Communication Studies at Murdoch University 1997 Repeat-The-Beat: i Declaration I declare that this dissertation is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary educational institution. ____________________ Christy Elizabeth Newman Repeat-The-Beat: ii Copyright License Permission to copy all or part of this thesis for study and research purposes is hereby granted. 1. Signed Christy Elizabeth Newman Date: November 3, 1997 2. Title of Thesis:Repeat-the-Beat: Industries, Genres and Citizenships in Dance Music Magazines Repeat-The-Beat: iii Abstract This thesis examines a particular cultural object: dance music magazines. It explores the co-imbrication of the magazines with dance music and considers how a reconfiguration of the field of genre theory can help to dismantle the generic separations of ‘textual’ and ‘industrial’ approaches to cultural objects. The main argument of the thesis is as follows. The magazine industries produce an object of cultural exchange which is made commercially viable through a narrowing of its target audiences. These audiences arise in the space created by the dance music industries’ negotiation of an imagined contest between 'underground' authenticity and 'mainstream' productivity. In turn, dance music magazines produce a powerfully exclusive space for the communication networks of the dance music genre by capitalising on the desire to stabilise genre and therefore taking up generic instability as a positive youth marketing strategy. -

Atmosphere Magazine

......••..,, ......... ... ..... •••••••• ..... ..•.....••••. ....... •. ••••••.... .. •.•.....• • • • •. I • .♦.....•••••. ...•....•.... > ..•••••••............ .. • •.•. •.•.•.•.•.•. •• • • • • • • • •• • •• •♦ • •• • • ...•••••••...... ••••.. •.• • •.•.•.• ♦ •••••••.. ••••••••••••••✓••••••• • • • • • • • •. •.•.•. •.•.•.• •....• .• .•..•..•..• .•.·.·.·.·.... G TEMPLE Ml ••••• ••••• • • •• • • •• •• •• •• •• •• •• • • •• •• •• •• •• •• •♦ • .........................• • • ♦ •••••••••••••••••• • JOY ROOM ••.. ♦. ••••••••••••••••••••••••...... ., .............. • ....• • • • •···················· • • • • .• • .• • • • • • • • • ♦ •••••••• . ... ...... ....... ............... • •• •••••..... ♦ ♦ . THUNDER ROOM .............• • • •• ............. ...................... ..... • ..........• ♦ •••••••••. ........... • ♦ •••••••••• DJ FACE ...... • .••••••••.......... ♦ ••. .. ..... • •••• ♦ •••••• . .♦ • .• .• .••••••••....... .....·.·..... ..... GROOVERIDER ...................................... ....................... ·.•.·.. • ............• • • • ♦ ••••••• • ••• ♦ ••• .• .• .• .• .• .• ..• • .• .• .♦. • . ............... ............ .• ♦ ••••• ♦ TONY TRAX ............. • ••••• ♦ • RODNEYT ..................................... ................. ♦ .......... •• •• •• • ••••••••• • • • • • • • • ........ • .♦....... •••• • ••. ♦ • • .......................... • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ♦ ••• ...................... ................... ♦ ....................... ........................................... • • •••••• • • • • • • • • • -

A Midsummer Night's Mash-Up

A Midsummer Night's Mash-up Adapting Shakespeare as a Canada Day Dance Party by MARK MCCUTCHEON n 1 July 2000, Toronto's Opera House became the unlikely set for a passing strange adapta- "participatory theatre" (8) wherein the dance floor "serves tion of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's as the stage for ... transformative experiences" (9) . By Dream. Serenity Industries, a Toronto dance transformative experiences, May means a process where- party promotion company, hired the Queen by successful dance parties join the individual dancers OStreet East Theatre turned concert hall to host A and DJs in a collectivity whose transcendent vibe can be Midsummer Night's Dream - a Canada Day rave . palpable, despite - or even because of - the event's ephemeral transience : "The evening's direction remains Theorizing the Theatricality of the Dance Party unknown until the participants engage with it" (10). Clearly, some preliminary explanations are required to However, "transforming" is also a specific DJ technique discuss a rave as a theatrical adaptation of Shakespeare . It for mixing the beats of two records . The resulting double is worth noting at the outset that this party belongs to an entendre suggests the myriad ways in which performance identifiable genre of rave adaptations of Shakespeare . On is at the heart of the rave experience: a cultural continuum 24 June 1989, the seminal London acid house party com- (a discontinuum, if you will) collaboratively produced by pany Sunrise hosted A Midsummer Night's Dream (see Fig . the explicitly theatrical performances of the DJs and MCs, 1). More recently, film has become a genre in which rave as well as the carnival of performances taking place aesthetics join Shakespearean scripts : Baz Luhrmanri s among party goers, promoters and everyone else in atten- William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet suggested that dance. -

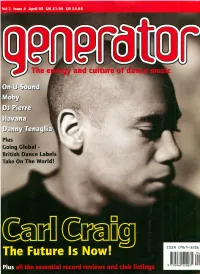

Generator Magazine, 4-8 One) to : Sven Vath Competition, Generator, Project for R&S, Due for Release in the Early Peartree Street, London, Ecl V 3SB

and culture of Plus Going Global - British Dance Labels Take On The World! ISSN 0969-5206 11 111 " 9 770969 ,,,o,, I! I OW HMV • KNOW Contents April 1995 Vol 2 Issue 3 Features 10 Moby 14 Move D 19 Riccardo Rocchi 20 Danny Tenaglia 24 Crew 2000 2 6 Carl Craig 32 DJ Pierre 37 Dimitri 38 A Bad Night Out? 40 Havana 44 On-U-Sound 52 Caroline Lavelle 54 Going Global! 70 DJ Rap 81 Millennium Records Live 65 Secret Knowledge 68 A Positive Life Regulars 5 Letters 8 From The Floor 50 Fashion 57 Album Reviews 61 Single Reviews 71 Listings 82 The World According To ... Generator 3 YOU IOlC good music, ri&11t? Sl\\\.tle, 12 KILLER MASTERCUTS FLOOR-FILLERS ~JIIA1fJ}J11JWJ}{@]1J11~&tjjiiliJ&kiMJj P u6-:M44kiL~ffi:t.t&8/W ~-i~11J#JaJJA/JliliID1il1- ~~11JID11ELJ.JfiZW-J!U11-»R dftlhiMillb~JfJJlkmt@U¾l E-.fiW!JJlJMiijifJ~)JJt).ilw,i1!J!in 11Y$#~1kl!I . ' . rJOJ,t'tJi;M)J4&,j~ letters.·• • Editor Dear Generator, Dear Generator, and wasting hours-worth of Tim Barr Que Pasa? Something seems to My friends and I are wondering conversationa l aimlessness in Assistant Editor (Advertising) have happened at Generator about a frequent visitor to your an attempt to discover exactly Barney York HQ. One minute, there I was letters page. It seems that the where it was you left those last thinking your magazine was military have moved up north three papers, or, indeed, your Art Direction & Design Paul Haggis & Derek Neeps well and t ruly firmed up with and installed someone with head. -

Ambient Music the Complete Guide

Ambient music The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 05 Dec 2011 00:43:32 UTC Contents Articles Ambient music 1 Stylistic origins 9 20th-century classical music 9 Electronic music 17 Minimal music 39 Psychedelic rock 48 Krautrock 59 Space rock 64 New Age music 67 Typical instruments 71 Electronic musical instrument 71 Electroacoustic music 84 Folk instrument 90 Derivative forms 93 Ambient house 93 Lounge music 96 Chill-out music 99 Downtempo 101 Subgenres 103 Dark ambient 103 Drone music 105 Lowercase 115 Detroit techno 116 Fusion genres 122 Illbient 122 Psybient 124 Space music 128 Related topics and lists 138 List of ambient artists 138 List of electronic music genres 147 Furniture music 153 References Article Sources and Contributors 156 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 160 Article Licenses License 162 Ambient music 1 Ambient music Ambient music Stylistic origins Electronic art music Minimalist music [1] Drone music Psychedelic rock Krautrock Space rock Frippertronics Cultural origins Early 1970s, United Kingdom Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments, electroacoustic music instruments, and any other instruments or sounds (including world instruments) with electronic processing Mainstream Low popularity Derivative forms Ambient house – Ambient techno – Chillout – Downtempo – Trance – Intelligent dance Subgenres [1] Dark ambient – Drone music – Lowercase – Black ambient – Detroit techno – Shoegaze Fusion genres Ambient dub – Illbient – Psybient – Ambient industrial – Ambient house – Space music – Post-rock Other topics Ambient music artists – List of electronic music genres – Furniture music Ambient music is a musical genre that focuses largely on the timbral characteristics of sounds, often organized or performed to evoke an "atmospheric",[2] "visual"[3] or "unobtrusive" quality. -

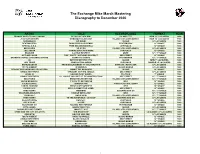

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020

The Exchange Mike Marsh Mastering Discography to December 2020 ARTIST TITLE RECORD LABEL FORMAT YEAR FRANKIE GOES TO HOLLYWOOD RELAX (12" SEX MIX) ISLAND / ZTT NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 JOCEYLYN BROWN SOMEBODY ELSES GUY ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY NEW 12" LACQUERS 1988 SHRIEKBACK GO BANG! ISLAND LP LACQUERS 1988 BEATMASTERS BURN IT UP (ACID REMIX) RHYTHM KING 12" SINGLE 1988 SPECIAL A.K.A. FREE NELSON MANDELA CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS SO GOOD ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY LP LACQUERS 1988 JELLYBEAN COMING BACK FOR MORE CHRYSALIS 12" SINGLE 1988 ERASURE A LITTLE RESPECT MUTE 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 OUTLAW POSSE THE * PARTY / OUTLAWS IN EFFECT GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 BRANDON COOKE & ROXANNE SHANTE SHARP AS A KNIFE PHONOGRAM 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 U2 WITH OR WITHOUT YOU ISLAND NEW 7" LACQUERS 1988 JUDI TZUKE COMPILATION ALBUM CHRYSALIS DOUBLE LP LACQUERS 1988 NAPALM DEATH FROM ENSLAVEMENT TO OBLITERATION EARACHE / REVOLVER LP LACQUERS 1988 TOOTS HIBBERT IN MEMPHIS ISLAND MANGO LP LACQUERS 1988 REGGAE PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA MINNIE THE MOOCHER ISLAND 12" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS STRAIGHT OUT THE JUNGLE GEE STREET LP LACQUERS 1988 LEVEL 42 HEAVEN IN MY HANDS POLYDOR 7" SINGLE 1988 JUNGLE BROTHERS I'LL HOUSE YOU (GEE ST. RECONSTRUCTION) GEE STREET 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 MICA PARIS BREATHE LIFE INTO ME ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 BLOW MONKEYS IT PAYS TO BE TWELVE RCA 12" SINGLE 1988 STEVEN DANTE IMAGINATION CHRYSALIS COOLTEMPO 12" SINGLE 1988 TANITA TIKARAM TWIST IN MY SOBRIETY WEA 10" SINGLE 1988 RICHIE RICH MY D.J. (PUMP IT UP SOME) GEE STREET 12" SINGLE 1988 TODD TERRY WEEKEND SLEEPING BAG UK 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 TRAVELING WILBURYS HANDLE WITH CARE WEA 12" / 7" SINGLE 1988 YOUNG M.C. -

Mike Marsh Discography

Mike Marsh Discography ARTIST TITLE RECORD LABEL FORMAT YEAR 02:54 SUGAR POLYDOR / FICTION DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 1789 CA IRA MON AMOUR UNIVERSAL MERCURY FRANCE CD SINGLE / DOWNLOAD 2011 0 8 0 0 1 VORAGINE WORKING PROGRESS CD ALBUM 2007 18 WHEELER THE HOURS AND THE TIMES CREATION CD SINGLE / 12" SINGLE 1996 18 WHEELER YEAR ZERO CREATION CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1996 49ERS GOT TO BE FREE ISLAND / 4TH & BROADWAY CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1992 4GOTTEN FLOOR THE FORGOTTEN FLOOR JATO MUSIC CD ALBUM 2008 808 STATE DON SOLARIS ZTT CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1996 808 STATE BOND ZTT CD SINGLE / 12" / 10" SINGLE 1996 808 STATE LOPEZ ZTT CD SINGLE / 12" SINGLE 1996 AARON BIRDS IN THE STORM WAGRAM / CINQ 7 CD ALBUM / DOWNLOAD 2010 ABC GREATEST HITS PHONOGRAM CD PRE-MASTERING 1990 ADAM CLAYTON & LARRY MULLEN MISSION : IMPOSSIBLE MOTHER 7" SINGLE 1996 ADAM KESHER CHALLENGING NATURE DISQUE PRIMEUR CD ALBUM / DOWNLOAD 2010 ADD N TO (X) AVANT HARD MUTE CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 1998 ADD N TO (X) REVENGE OF THE BLACK REGENT MUTE CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1999 ADD N TO (X) LOUD LIKE NATURE MUTE CD ALBUM / LP LACQUERS 2002 ADDIE BRIK LOVED HUNGRY BREAKIN' BEATS CD ALBUM 2003 ADDIE BRIK STRIKE THE TENT ADDIE BRIK CD ALBUM 2008 ADELE SET FIRE TO THE RAIN (THOMAS GOLD REMIX) XL RECORDINGS CD SINGLE / DOWNLOAD 2011 ADRENALIN JUNKIES ADRENALIN JUNKIES LA PLAGE CD ALBUM 2008 ADSTEDT DREAMING WIDE AWAKE VERATONE SWITZERLAND DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 AFTERGLOW NEVER GROW OLD EP JACK McDONALD DOWNLOAD SINGLE 2012 AGENT PROVOCATEUR RED TAPE EPIC CD SINGLE / 12" / 7" SINGLE 1996 -

Nummer Punten Titel Artiest Jaartal 1 Born Slippy Underworld 1995 2 Insomnia Faithless 1995 3 Dominator Human Resource 1991 4 Ca

2010 nummer punten titel artiest jaartal 1 Born Slippy Underworld 1995 2 Insomnia Faithless 1995 3 Dominator Human Resource 1991 4 Café del Mar Energy 52 1993 5 Go Moby 1991 6 Don't you want me Felix 1992 7 Flight 643 Tiësto 2001 8 Plastic Dreams Jaydee 1992 9 God Is A DJ Faithless 1998 10 The House Of God D.H.S. 1991 11 No Good (Start The Dance) Prodigy 1994 12 James Brown is dead LA Style 1991 13 Show Me Love Robin S 1992 14 Pull Over Speedy J 1991 15 Children Robert Miles 1995 16 Traffic Tiësto 2003 17 Age of love Age of love 1992 18 For An Angel Paul van Dyk 1998 19 Sandstorm Darude 1999 20 Avalanche Marco Carola 2001 21 Adagio for Strings Tiësto 2005 22 Better Off Alone Alice Deejay feat DJ Jurgen 1998 23 Firestarter Prodigy 1996 24 Around The World Daft Punk 1996 25 Mary Go Wild Grooveyard 1996 26 Drop It Scoop 1999 27 Can You Feel It? C.L.S. 1991 28 A Deeper Love Clivilles & Cole 1991 29 Money (Reese mix) Cameo 1992 30 The First Rebirth Jones & Stephenson 1993 31 Smack My Bitch Up Prodigy 1997 32 Meet Her At The Love Parade Da Hool 1997 33 Lethal Industry Tiësto 2001 34 Do you know what I mean? #1 1993 35 One More Time Daft Punk 2000 36 Simulated Marco V 2001 37 9 PM A.T.B 1998 38 Faster Stronger... Daft Punk 2001 39 Silence (DJ Tiësto mix) Delerium Ft. Sarah Mclachlan 2000 40 We Come 1 Faithless 2001 41 Monkey Wah Radical Rob 1991 42 House of justice DJ José & G-Spott 1999 43 Get ready for this 2 Unlimited 1991 44 Godd Marco V 2001 45 Missing Everything But The Girl & Todd Terry 1994 46 Man with the red face Laurent Garnier 2000 2010 nummer punten titel artiest jaartal 47 Out of Space Prodigy 1992 48 Zombie Nation Kernkraft 400 1999 49 The Launch Dj Jean 1999 50 Solid Session Format 1 1991 51 Unfinished Sympathy Massive Attack 1991 52 Seven Days & One Week B.B.E. -

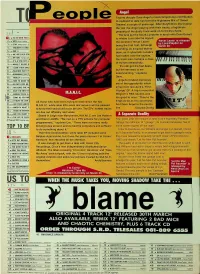

Tfpeople a ^ TIME to MAKE YC TOP 10 BP 57 TOO GOOD to BE Tl 66 the DISAPPOINTED US to H

TfPeople Techno disciple Dave Angel's most cons| to clubland to dale has been the Nightmare Mix of 'Sweet Dreams' a couple of years ago. After Eurythmics discovered the real live Angel playing with their tracks, a legitimate pressing of the dusty track went on to hit the charts. The tune put the South Londoner in touch with Dave Dorrell, to whose Love label he signed, the excellent 'Never Leave' sounding,being the firstas all fruit. good Although techno does, as if cybernetic lunatics have taken over the asylum, the track also contains a dose | of human melancholy. but"It's the still eeriness got the is fastme beats, experimenting," explains Dave. Angel's fondest memories a ^ TIME TO MAKE YC are of the opportunity which arose from last April's 'First Voyage' EP. A trip to record at | Belgium's R&S studios was too good to miss. "They're the I All those who have been trying to track down the two kings as far as I'm concerned." IT M.A.N.I.C. white label EPs since last autumn will be pleased And Dave Angel is the next in to know their search will soon be over. The EPs' hottest tracks line. Davydd Chong I areBased due outin Leighofficially near next Manchester, week. M.A.N.I.C. are Lee Hudson A Separate Reality and Kieron Jolliffe. "We met on a YTS scheme for computer Four years after the closure of New York's legendary Paradise programmers," explains Lee. "There were not many really Garage the definition of "garage", its musical namesake, has in TOP 10 BP kicking tunes around, and we had the computers and software someEnter cases DJ/producer slipped offJon the Williams mark.