THE ONE THAT GETS YOU HOOKED I Think It’S Fair to Consider Reading Science Fiction to Be an Addictive Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

Discussion About Edwardian/Pulp Era Science Fiction

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Jess Nevins July 2019 Jess Nevins is the author of “the Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana” and other works on Victoriana and pulp fiction. He has also written original fiction. He is employed as a reference librarian at Lone Star College-Tomball. Nevins has annotated several comics, including Alan Moore’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Elseworlds, Kingdom Come and JLA: The Nail. Gary Denton: In America, we had Hugo Gernsback who founded science fiction magazines, who were the equivalents in other countries? The sort of science fiction magazine that Gernsback established, in which the stories were all science fiction and in which no other genres appeared, and which were by different authors, were slow to appear in other countries and really only began in earnest after World War Two ended. (In Great Britain there was briefly Scoops, which only 20 issues published in 1934, and Tales of Wonder, which ran from 1937 to 1942). What you had instead were newspapers, dime novels, pulp magazines, and mainstream magazines which regularly published science fiction mixed in alongside other genres. The idea of a magazine featuring stories by different authors but all of one genre didn’t really begin in Europe until after World War One, and science fiction magazines in those countries lagged far behind mysteries, romances, and Westerns, so that it wasn’t until the late 1940s that purely science fiction magazines began appearing in Europe and Great Britain in earnest. Gary Denton: Although he was mainly known for Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle also created the Professor Challenger stories like The Lost World. -

LESSON 5: Boneshaker by Cherie Priest

LESSON 5: Boneshaker by Cherie Priest On the forum, I gave you the following assignment: Read the first 5 pages of Boneshaker by Cherie Priest. List the Steampunk elements you find. Then list the ESSENTIAL Steampunk genre elements, and then the Character descriptions, then setting Your chart will look something like this: STEAMPUNK ...................... ESSENTIAL ...................CHARACTER ...........SETTING ELEMENTS ......................... ELEMENTS.....................ELEMENTS...............ELEMENTS black overcoat black overcoat 11 crooked stairs 11 crooked stairs and so on you can find Boneshaker here at Amazon The table part didn’t come out very well so here’s a better version. I added the word “ALL” to the column labels because I wanted you to understand that in those columns I’m not looking for any specific elements other than those labeled. For instance, under “CHARACTER ELEMENTS (ALL)” give all the character elements you find, not just elements pertaining to the Steampunk genre. STEAMPUNK ESSENTIAL CHARACTER SETTING ELEMENTS (ALL) STEAMPUNK ELEMENTS ELEMENTS (ALL) ELEMENTS (ALL) Black overcoat Black overcoat 11 crooked stairs 11 crooked stairs Goth, Gadgets & Grunge: Steampunk Stories with Style!© By Pat Hauldren LESSON 5: Boneshaker by Cherie Priest / 2 If you’ll notice on the link I provided for Boneshaker at Amazon.com, it’s listed as “ (Sci Fi Essential Books) “ and baby, that’s where *I* want to be! I couldn’t find a specific definition for exactly what that term meant at Amazon.com, but just from the term itself, you can tell it’s the list of books that, while aren’t classics yet, are becoming so for various reasons. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Banerjee [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India Suparno Banerjee Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Suparno, "Other tomorrows: postcoloniality, science fiction and India" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3181. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. OTHER TOMORROWS: POSTCOLONIALITY, SCIENCE FICTION AND INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of English By Suparno Banerjee B. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2000 M. A., Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India, 2002 August 2010 ©Copyright 2010 Suparno Banerjee All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My dissertation would not have been possible without the constant support of my professors, peers, friends and family. Both my supervisors, Dr. Pallavi Rastogi and Dr. Carl Freedman, guided the committee proficiently and helped me maintain a steady progress towards completion. Dr. Rastogi provided useful insights into the field of postcolonial studies, while Dr. Freedman shared his invaluable knowledge of science fiction. Without Dr. Robin Roberts I would not have become aware of the immensely powerful tradition of feminist science fiction. -

Forbidden Planet” (1956): Origins in Pulp Science Fiction

“Forbidden Planet” (1956): Origins in Pulp Science Fiction By Dr. John L. Flynn While most critics tend to regard “Forbidden Planet” (1956) as a futuristic retelling of William Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”—with Morbius as Prospero, Robby the Robot as Arial, and the Id monster as the evil Caliban—this very conventional approach overlooks the most obvious. “Forbidden Planet” was, in fact, pulp science fiction, a conglomeration of every cliché and melodramatic element from the pulp magazines of the 1930s and 1940s. With its mysterious setting on an alien world, its stalwart captain and blaster-toting crew, its mad scientist and his naïve yet beautiful daughter, its indispensable robot, and its invisible monster, the movie relied on a proven formula. But even though director Fred Wilcox and scenarist Cyril Hume created it on a production line to compete with the other films of its day, “Forbidden Planet” managed to transcend its pulp origins to become something truly memorable. Today, it is regarded as one of the best films of the Fifties, and is a wonderful counterpoint to Robert Wise’s “The Day the Earth Stood Still”(1951). The Golden Age of Science Fiction is generally recognized as a twenty-year period between 1926 and 1946 when a handful of writers, including Clifford Simak, Jack Williamson, Isaac Asimov, John W. Campbell, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Frederick Pohl, and L. Ron Hubbard, were publishing highly original, science fiction stories in pulp magazines. While the form of the first pulp magazine actually dates back to 1896, when Frank A. Munsey created The Argosy, it wasn’t until 1926 when Hugo Gernsback published the first issue of Amazing Stories that science fiction had its very own forum. -

Zen in the Art of Writing – Ray Bradbury

A NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Ray Bradbury has published some twenty-seven books—novels, stories, plays, essays, and poems—since his first story appeared when he was twenty years old. He began writing for the movies in 1952—with the script for his own Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. The next year he wrote the screenplays for It Came from Outer Space and Moby Dick. And in 1961 he wrote Orson Welles's narration for King of Kings. Films have been made of his "The Picasso Summer," The Illustrated Man, Fahrenheit 451, The Mar- tian Chronicles, and Something Wicked This Way Comes, and the short animated film Icarus Montgolfier Wright, based on his story of the history of flight, was nominated for an Academy Award. Since 1985 he has adapted his stories for "The Ray Bradbury Theater" on USA Cable television. ZEN IN THE ART OF WRITING RAY BRADBURY JOSHUA ODELL EDITIONS SANTA BARBARA 1996 Copyright © 1994 Ray Bradbury Enterprises. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Owing to limitations of space, acknowledgments to reprint may be found on page 165. Published by Joshua Odell Editions Post Office Box 2158, Santa Barbara, CA 93120 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bradbury, Ray, 1920— Zen in the art of writing. 1. Bradbury, Ray, 1920- —Authorship. 2. Creative ability.3. Authorship. 4. Zen Buddhism. I. Title. PS3503. 167478 1989 808'.os 89-25381 ISBN 1-877741-09-4 Printed in the United States of America. Designed by The Sarabande Press TO MY FINEST TEACHER, JENNET JOHNSON, WITH LOVE CONTENTS PREFACE xi THE JOY OF WRITING 3 RUN FAST, STAND STILL, OR, THE THING AT THE TOP OF THE STAIRS, OR, NEW GHOSTS FROM OLD MINDS 13 HOW TO KEEP AND FEED A MUSE 31 DRUNK, AND IN CHARGE OF A BICYCLE 49 INVESTING DIMES: FAHRENHEIT 451 69 JUST THIS SIDE OF BYZANTIUM: DANDELION WINE 79 THE LONG ROAD TO MARS 91 ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS 99 THE SECRET MIND 111 SHOOTING HAIKU IN A BARREL 125 ZEN IN THE ART OF WRITING 139 . -

PDF Text Files

The Canadian Fancyclopedia: S – Version 1 (June 2009) An Incompleat Guide To Twentieth Century Canadian Science Fiction Fandom by Richard Graeme Cameron, BCSFA/WCSFA Archivist. A publication of the British Columbia Science Fiction Association (BCSFA) And the West Coast Science Fiction Association (WCSFA). You can contact me at: [email protected] Canadian fanzines are shown in red, Canadian Apazines in Green, Canadian items in purple, Foreign items in blue. S SACRED TRUST / THE SAME TO YOU / SAMIZDAT / SANSEVIERIA / SAPPHIRE DREAMS / SAPPHIRE MARMALADE / THE SASQUATCH SASKATCHEWANIAN / SCHMAGG / SCHMAGG MONTHLY / SCICON / SCIENCEERS / SCIENCE-FANTASY / SCIENCE FICTION / THE SCIENCE FICTION COLLECTOR / SCIENCE FICTION LEAGUE / SCIENCE FICTION STUDIES / SCIENTIFIC FICTION / SCIENTIFICTION / SCIENTILLO / SCIFFY - SKIFFY / SCI-FI / SCUM / SCUTTLE BUTT / SECOND FANDOM / SECOND TRANSITION / THE SENATORS OF FANDOM / SERCON / SERCON POPCULT LITCRIT FANMAG / SERENDIPITY / SERIOUS CONSTRUCTIVE / SEVAGRAM / SF3 NEWSLETTER / SFA DIGEST / SFAV / SFEAR / SHADOWGUARD / SHAGGOTH 6 / SHON'AI / SHORT TREKS / SHRDLU ETAOIN / SHUTTLE BUTT / SIDETREKKED / SIGH / SIGN OF THE DRUNKEN DRAGON / SILPING / THE SILVER APPLE BRANCH / SIMULACRUM / SING YE NOW PRAISES OF CORFLU / SMASH! / SMOTE / SMUT / SNEEOLOGY / "SOONEST" / SOOTLI / SOLARIS / SONO-DISCS / SON OF MACHIAVELLI / SPACE CADET / SPACED-OUT LIBRARY / SPACE OPERA / THE SPAYED GERBIL / THE SPECULATIVE FICTION SOCIETY OF MANITOBA YEARBOOK / SPINTRIAN / SPO / SPRINGTIME WILL NEVER BE THE SAME / 1993 SPUZZUM WORLDCON BID / SPWAO / SPWAO SHOWCASE / SPWSSTFM / STAGE ONE / STAPLE WAR (FIRST) / STAR BEGOTTEN / STARDATE / STARDOCK / STAR DUST / STAR FROG / STAROVER / STAR SONGS / STAR STONE / STATE OF THE ART / STF / STILL NOT THE BCSFAZINE #100 / STRANGE DISTOPIAS / SUPRAMUNDANE STORIES / SURREY FAN ASSOCIATION - SURREY FAN CONTINGENT / STYX / THE SWAMP GAS JOURNAL / SWILL / SYNAPSE SACRED TRUST -- Faned: Murray Moore. -

Guest Editorial

Guest E ditorial Allen M. Steele WHERE WE CAME FROM IS WHERE WE’RE GOING The following essay is adapted from a speech made at the second Asian Pacific Sci - ence Fiction Convention (Apsfcon 2019) in Beijing, China, on May 26, 2019. I’m not only a science fiction writer, but also a science fiction historian, albeit of the armchair variety. The history of the SF genre fascinates me just about as much as any SF novel I’ve ever read. I’ve often used SF history as the background for my own work, such as my novel Arkwright , and lately my interest has only become stronger as I’ve explored the genre’s origins. One of the most wonderful things that’s come out of my studies is an appreciation for SF’s roots and just how truly international they are. More importantly, though, if we accept the idea that examining history can be a reliable means of forecasting the future—a major reason why it’s important to preserve the past and study it—then it’s possible that we may be able to perceive the direction where we’re headed by looking back to see where we’ve come from. Thus, a brief, and by no means complete, history of science fiction: Like science fiction’s close cousin, fantasy, SF has its roots in fables and myth-olo - gy, stories of the fantastic as opposed to realistic fiction. Much of this, particularly the imaginative literature published prior to the mid-nineteenth century, could be considered proto-SF. -

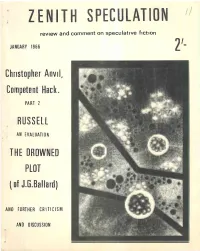

Zenith-Speculation 11 Weston

ZENITH SPECULATION ' review and comment on speculative fiction JANUARY 1966 2'- Christopher Anvil, Competent Hack. PART 2 RUSSELL A AN EVALUATION THE DROWNED PLOT (of J.G.Ballard) ANO FURTHER CRITICISM AND DISCUSSION REVIEW AND COMMENT UPON SPECULATIVE FICTION January 1966 Vcl.l, No. 11 ZENITH SPECULATION is an amateur Articles magazine containing criticism & RUSSELL 4 discussion of speculative fiction Richard Gordon It is published quarterly from THE DROWNED PLOT (of J.G.Ballard) 10 the editorial address, tn which J.P.Patrizio all articles,. artwork, comments ....ABOUT TELEPATHIST 18 on the magazine, and UK subscrip John Brunner tions should be addressed. CHRISTOPHER ANVIL, COMPETENT HACK 27 No payment can at present be made Peter R.Weston (Part 2.) for published material, but com plimentary copies will be sent to Departments contributors tn the magazine. CONTENTS & EDITORIAL 1 ZENITH will be exchanged with DOUBLE BOOKING 19 other amateur magazines, as pre (Book Reviews) arranged with the editor. Archie & Boryl Mercer THE MELTING POT 1 35 Subscriptions are 10/- for five (Letters from readers) issues, and should be sent to the editor. Single copies each 2/-, U.S. subscriptions are /1.50 for all unsigned work is by the editor five issues, and should be sent to our Agent, Albert J. Lewis,c/<. 1825 Greenfield Ave., J»os Angeles California, Single copies JO/ FRONT COVER by Joseph Zajackowski Column advertising rates; 6d for 10 words (10/). Rates for display Interior illustrations by Latto, advertisements on request. Zajackowski, & Pitt. Edited and Published by Pater R. Weston, 9 Porlock Crescent, Northfield, Birmingham, JI. -

Nanotech Ideas in Science-Fiction-Literature

Nanotech Ideas in Science-Fiction-Literature Nanotech Ideas in Science-Fiction-Literature Text: Thomas Le Blanc Research: Svenja Partheil and Verena Knorpp Translation: Klaudia Seibel Phantastische Bibliothek Wetzlar Special thanks to the authors Karl-Ulrich Burgdorf and Friedhelm Schneidewind for the kind permission to publish and translate their two short stories Imprint Nanotech Ideas in Science-Fiction-Literature German original: Vol. 24 of the Hessen-Nanotech series by the Ministry of Economics, Energy, Transport and Regional Development, State of Hessen Compiled and written by Thomas Le Blanc Svenja Partheil, Verena Knorpp (research) Phantastische Bibliothek Wetzlar Turmstrasse 20 35578 Wetzlar, Germany Edited by Sebastian Hummel, Ulrike Niedner-Kalthoff (Ministry of Economics, Energy, Transport and Regional Development, State of Hessen) Dr. David Eckensberger, Nicole Holderbaum (Hessen Trade & Invest GmbH, Hessen-Nanotech) Editor For NANORA, the Nano Regions Alliance: Ministry of Economics, Energy, Transport and Regional Development, State of Hessen Kaiser-Friedrich-Ring 75 65185 Wiesbaden, Germany Phone: +49 (0) 611 815 2471 Fax: +49 (0) 611 815 49 2471 www.wirtschaft.hessen.de The editor is not responsible for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of this information nor for observing the individual rights of third parties. The views and opinions rendered herein do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editor. © Ministry of Economics, Energy, Transport and Regional Development, State of Hessen Kaiser-Friedrich-Ring 75 65185 Wiesbaden, Germany wirtschaft.hessen.de All rights reserved. No part of this brochure may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. -

In the Beginning – a Very Abbreviated History of the Earliest Days of Science Fiction Fandom

In the Beginning – A Very Abbreviated History of the Earliest Days of Science Fiction Fandom by Rich Lynch The history of science fiction fandom in certain ways is not unlike the geological history of the Earth. Back in the earliest geological era, most of Earth’s land mass was combined into one super- continent, Pangaea. The earliest days of science fiction fandom were comparable, in that once there was a solitary fan group, the Science Fiction League (or SFL), that attempted to bring most of the science fiction fans together into a single organization. The SFL was created by publisher Hugo Gernsback in the May 1934 issue of Wonder Stories. Science fiction fandom was already in existence by then, but it mostly consisted of isolated individuals publishing fan magazines with one or two fan clubs existing in large population centers. This would soon change. That issue of Wonder sported the colorful emblem of the SFL on its cover: a wide-bodied multi-rocketed spaceship passing in front of the Earth. Inside, Gernsback’s four-page editorial summed up the SFL as an organization “for the furtherance and betterment of the art of science fiction” and implored fans to join the new organization and “spread the gospel of science fiction.” The response was almost immediate. Fans from various parts of the United States wrote enthusiastic letters, many of which were published by Gernsback in Wonder’s letters column. Some of the respondents started chapters of the SFL in various cities, and most of the science fiction clubs that already existed became affiliates of the SFL.