What Great Human Beings We'll Be Someday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dragon Con Progress Report 2021 | Published by Dragon Con All Material, Unless Otherwise Noted, Is © 2021 Dragon Con, Inc

WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG INSIDE SEPT. 2 - 6, 2021 • ATLANTA, GEORGIA • WWW.DRAGONCON.ORG Announcements .......................................................................... 2 Guests ................................................................................... 4 Featured Guests .......................................................................... 4 4 FEATURED GUESTS Places to go, things to do, and Attending Pros ......................................................................... 26 people to see! Vendors ....................................................................................... 28 Special 35th Anniversary Insert .......................................... 31 Fan Tracks .................................................................................. 36 Special Events & Contests ............................................... 46 36 FAN TRACKS Art Show ................................................................................... 46 Choose your own adventure with one (or all) of our fan-run tracks. Blood Drive ................................................................................47 Comic & Pop Artist Alley ....................................................... 47 Friday Night Costume Contest ........................................... 48 Hallway Costume Contest .................................................. 48 Puppet Slam ............................................................................ 48 46 SPECIAL EVENTS Moments you won’t want to miss Masquerade Costume Contest ........................................ -

Welcome to Worship At

Welcome to worship at Alamo Heights United Sunday Morning Worship Methodist Church. in the Sanctuary Welcome at 8:30, 9:30 & 11:00 a.m. Rev. David McNitzky, Lead Pastor Rev. Donna Strieb, Worship Pastor to Worship I t is our hope that this information will an- In the Christian Life Center Alamo Heights United Methodist Church swer questions about the acts of worship. at 9:30 & 11:00 a.m. As God’s people, we are called to practice Rev. Dinah Shelly, Lead Pastor weekly worship with the community. At the Rev. Darrell Smith heart of worship is adoration of God the Fa- Rev. Ryan Jacobson Rev. Matthew Scott ther, Son and Holy Spirit. Taizé Service First Wednesday of each month at In worship: 6:30 p.m. in the Garden Chapel • we are given words of praise Rev. Donna Strieb, Lead Pastor and gratitude; • we bring the needs of our lives, OUR MISSION: our church and our world before God; to partner with God in bringing • we hear the Story of God, God’s deliver- the kingdom of heaven to earth ance of God’s people, and the great and by making disciples of Jesus Christ unending love that God has for all the world; OUR VALUES: (STARS) Sonship, Text, Action, Relationship & Spirit • we remember who we are, God’s beloved sons and daughters; • we speak the text that guides our lives and hear it proclaimed; • we hear that our actions help bring in the Kingdom; • we remember that we are called to rela- tionship with God, with each other and with our neighbor; • we remember that Holy Spirit continually leads, guides and surrounds us. -

Copyright © 2012 Matthew Scott Wireman All Rights Reserved. the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Has Permission to Reprodu

Copyright © 2012 Matthew Scott Wireman All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THE SELF-ATTESTATION OF SCRIPTURE AS THE PROPER GROUND FOR SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY ___________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary ___________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ___________ by Matthew Scott Wireman December 2012 APPROVAL SHEET THE SELF-ATTESTATION OF SCRIPTURE AS THE PROPER GROUND FOR SYSTEMATIC THEOLOGY Matthew Scott Wireman Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Stephen J. Wellum (Chair) __________________________________________ Michael A. G. Haykin __________________________________________ Chad Owen Brand Date ______________________________ To Ashley, Like a lily among thorns, so is my Beloved among the maidens. Song of Songs 2:2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . x Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 Thesis . 2 The Historical Context for the Doctrine . 5 The Current Evangelical Milieu . 15 Methodology . 18 2. A SELECTIVE AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF SCRIPTURE’S SELF-WITNESS . 31 Patristic Period . 32 Reformation . 59 Post-Reformation and the Protestant Scholastics . 74 Modern . 82 Conclusion . 95 3. A SUMMARY AND EVALUATION OF THE POST-FOUNDATIONAL THEOLOGICAL METHOD OF STANLEY J. GRENZ AND JOHN R. FRANKE . 97 Introduction . 97 iv Denying Foundationalism and the Theological Method’s Task . 98 The Spirit’s Scripture . 116 Pannenbergian Coherentism and Eschatological Expectation . 123 Situatedness . 128 Communal Key . 131 Conclusion . 141 4. THE OLD TESTAMENT PARADIGM OF YHWH’S WORD AND HIS PEOPLE . 144 Sui Generis: “God as Standard in His World” . -

Caveat Lector

Vol. 15, Issue 2 The Caveat Lector The “When Should I Start Making My CANs” Edition “Well okay, pressing on then.” - Ron C.C. Cuming Managing Editors Table of Contents Christine Miller Janelle White Letter From the Editors………………………………………………………………………………………...3 Message from the Treasurer…………………………………………………………………………………4 Editorial Board Tava Burton Dear Sue…………….……………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Shivaun Eberle LOOK AT THIS PHOTOGRAPH: Fall Formal……………………………………………………………..6 Connor Ferguson Important Dates…………………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Darin Gette Erik Heuck Why Are 3Ls So Damn Great?..........................................................................................7 Matthew Scott Law Remix of R. Kelly - Ignition (Remix)…………………………………………………………………8 Emily Sutherland Another Message from the Legal Follies Board……………………………………………………..8 Mission Statement Match the Facebook Status to the Law Student…………………………………………………….9 The Caveat Lector exists to Parents in Law: What Being a Parent in Law School Has Taught Me…………………….10 be redundant. It also exists to Places to Cry……………………………………………………………………………………………………..12 publish and make available information and creative Is USask Law Losing its “Friendly” Moniker?................................................................13 works from law students for Some Memes…………………………………………………………………………………………………….14 law students, all while Between Fern & Ficus: Sit-Downs at Salamander Palace……………………………………..16 maintaining a standard of journalistic integrity. Well, So you think you want to transfer -

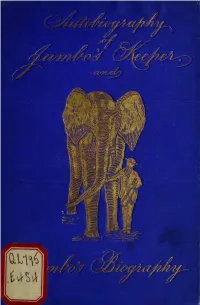

Autobiography of Matthew Scott, Jumbo's Keeper ... : Also Jumbo's

}tm v.> (IL^o^.fcj^ J '5. r & 3 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/autobiographyofmOOscot ) MEDAL PRESENTED BY THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LON- DON "TO MATTHEW SCOTT, FOR HIS SUCCESS IX BREED- ING FOREIGN ANIMALS IN THE SOCIETY'S GARDENS, 1866." {Side representing Kingdom of Beasts. representing Kingdom of Birds.) AUTOBIOGRAPHY MATTHEW SCOTT JUMBOS KEEPER FORMERLY OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY'S GABDENS, LONDON, AND RECEIVER OF SIR EDWIN LANDSEER MEDAL IN 1866 ALSO JUMBO'S BIOGRAPHY By the Same Author BRIDGEPORT, CONN. TROWS PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING CO., NEW YORK 1885 Q,Un< COPYRIGHT, 1885, BY MATTHEW SCOTT AND THOMAS E. LOWE Bridgeport, Conn. DEDICATION. I take great pleasure in dedicating this book, containing my autobiography and the biography of Junibo, to the people of the United States of America and Great Britain. I have travelled through the United States, North, East, South, and West, and have received in my travels the greatest kindness. If " Jumbo " could but speak, I know he would endorse what I say here. I have had the same experience in Great Britain, and the spirit of gratitude impels me to acknowledge my appreciation of the good will of the people of both countries, b DEDICATION. by dedicating my humble efforts to them, hoping that this attempt may be received with the same kindness that has been always extended to me in person. Respectfully, Matthew Scott. Bridgeport, Conn., January 14, 1885. MY AUTOBIOGRAPHY. CHAPTER I MY BIRTH-PLACE AND START IN LIFE. I purpose giving to the world, for the benefit of my fellow-men, my humble and truthful history. -

Copyright by Matthew Scott Archer 2004

Copyright by Matthew Scott Archer 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Matthew Scott Archer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Living the Master Plan Committee: ____________________________ Kathleen Stewart, Supervisor ____________________________ Pauline Strong ____________________________ John Hartigan ____________________________ Kamran Ali ____________________________ Ronald Greene Living the Master Plan by Matthew Scott Archer, M.A., B.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Texas at Austin May 2004 Living the Master Plan Publication No.________ Matthew Scott Archer, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2004 Supervisor: Kathleen Stewart I think of Living the Master Plan as an experimental ethnography. It might be better to say, in the words of Deleuze and Guattari, that it is a cartography. Whichever you prefer to call it, it is certainly an attempt to write critically about contemporary trends in American culture. I use multiple sites and subjects, including myself, to chart out the lines and machines which give shape to our lives. My map will take us into emerging forms of belonging, where community and corporatism converge and capitalist modes of valorization become our ethical foundation. Besides simply describing these emerging entities, I hope to provide a new context in which to evaluate them. Homeowners’ Associations, Master Planned Communities, and the property management firms specializing in their management are my privileged sites throughout. I map them out not only as new versions of community, but also as expressions of State desire. -

2019 AKC Obedience Classic Eligibility List

2019 AKC Obedience Classic Eligibility List Eligibility Regnum Prefix Titles Dog Name Suffix Titles Call Name Breed Owner(s) Novice TS24526801 Ghillie Dhu Connolly CD BN RI THDN CGCA CGCU TKN Affenpinscher Ken Stowell/Alison Fackelman Novice HP43185101 GCHS DC Bakura Suni Formula One CD RA MC LCX2 BCAT CGC TKN Afghan Hound Lynda Hicks/Toni D King/James Hicks Novice HP45411601 MACH Popovs Purrfection At Cayblu CD RE SC MXG MJC RATO Suzette Afghan Hound Cathy Kirchmeyer Novice HP52788106 Zoso's Sweet Sensation CD BN BCAT CGC Afghan Hound Kate E Maynard Novice RN27679104 Coldstream Lavender And Lace CD BN RN Airedale Terrier Darvel Kich Novice RN28189802 Kynas Glitzy Glam China Girl CD BN RI CGC Airedale Terrier Joyce Contofalsky/Craig Contofalsky Novice RN22466805 CH Monterra Big Sky Traveler CD PCD BN RI Stanley Airedale Terrier Christine Hyde Novice RN25552603 Mulberry Days For Sparkling Zoom CD RN Airedale Terrier Susan J Basham/Edward L Basham Novice RN25552608 Mulberry's Twilight Breeze Way CD Airedale Terrier Susan J Basham/Edward L Basham Novice PAL262089 Hachiko Of Sparta TN CD BN CA BCAT CGC Akita Armelle Le Guelte Novice WS36556101 CH Snokist I'M No Knock Off At Awanuna CD Alaskan Malamute Beverly Pfeiffer/Mr. Richard B Pfeiffer Novice WS51419804 CH Vykon's Justified CD BN RE CGC TKN Alaskan Malamute Vicky Jones Novice MA40540901 Abbey Rd's Piper Vanwilliams CD ACT2 CGC TKP PIPER All American Dog BETH WILLIAMS/ERIC VAN HOUTEN Novice MA66217301 Addison River Rose CD RN CGC TKN 841875051 All American Dog Bryana Anthony Novice MA34347501 -

The Anatomy of Anatomia: Dissection and the Organization of Knowledge in British Literature, 1500-1800

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 The na atomy of anatomia: dissection and the organization of knowledge in british literature, 1500-1800 Matthew cottS Landers Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Landers, Matthew Scott, "The na atomy of anatomia: dissection and the organization of knowledge in british literature, 1500-1800" (2009). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1390. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1390 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE ANATOMY OF ANATOMIA: DISSECTION AND THE ORGANIZATION OF KNOWLEDGE IN BRITISH LITERATURE, 1500-1800 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fi lfi llment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Matthew Scott Landers B.A., University of Dallas, 2002 May 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Because of the sheer scale of my project, it would have been impossible to fi nish this dissertation without the opportunity to do research at libraries with special collections in the history of science. I am extremely greatful, as a result, to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation at the University of Oklahoma for awarding me a fellowship to the History of Science Collections at Bizzell Library; and to Marilyn Ogilvie and Kerry Magruder for their kind assistance while there. -

Major Samantha Carter

Richard Dean Anderson A1 Autograph Card as Colonel Jack O'Neill C3 Costume Card Major Samantha Carter Teal'c I SketchaFEX Stargate SG-1 season 4 Teal'c II SketchaFEX Stargate SG-1 season 4 Michael Shanks and DA1 Autograph Card Amanda Tapping Relic Card of 60's Style R9 Relic Card Poster from "1969" G2 Kneel Before Your God Apophis A67 Autograph Card Claudia Black as Vala A70 Autograph Card Richard Dean Anderson A73 Autograph Card Isaac Hayes as Tolok Dan Castellaneta as Joe A76 Autograph Card Spencer Christopher Judge as DA2 Autograph Card Teal'c and Tony Amendola as Bra'tac Claudia Black as Vala and DA3 Autograph Card Michael Shanks as Dr. Daniel Jackson Ben Browder as Lt. Col. A85 Autograph Card Cameron Mitchell Michael Shanks and Ben DA4 Autograph Card Browder PC1 Stargate Patch Cards Colonel Jack O'Neill PC2 Stargate Patch Cards Dr. Daniel Jackson Lt. Colonel Samantha PC4 Stargate Patch Cards Carter Claudia Black as Vala A108 Autograph Card Mal Doran A96 Autograph Card Rene Auberjonois as Alar Amanda Tapping as Autograph Card Samantha Christopher Judge as Autograph Card Teal'c C56 Costume Card President Landry Beau Bridges as Major A86 Autograph Card General Hank Landry David Hewlett as Dr. Autograph Card Rodney McKay David Hewlett as Dr. Autograph Card Rodney McKay Amanda Tapping as Autograph Card Major Carter Jason Momoa as Ronon Autograph Card Dex Vala Mal Dual Costume Card Stargate Heroes Doran Samantha Dual Costume Card Stargate Heroes Carter Michael Shanks as Dr. Jackson - Autographed Costume Card Beau Bridges as Major General Hank Landry - Autographed Costume Card Amanda Tapping as Major Carter - Autographed Costume Card Richard Dean Anderson - Autographed Costume Card R75 Bug Prop Card Stargate SG-1 Season 5 SketchaFEX Checklist 3. -

Stargate Heroes Checklist

Stargate Heroes Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Jack O'Neill [ ] 02 Jack O'Neill [ ] 03 Jack O'Neill [ ] 04 Jack O'Neill [ ] 05 Jack O'Neill [ ] 06 Jack O'Neill [ ] 07 Jack O'Neill [ ] 08 Jack O'Neill [ ] 09 Jack O'Neill [ ] 10 Samantha Carter [ ] 11 Samantha Carter [ ] 12 Samantha Carter [ ] 13 Samantha Carter [ ] 14 Samantha Carter [ ] 15 Samantha Carter [ ] 16 Samantha Carter [ ] 17 Samantha Carter [ ] 18 Samantha Carter [ ] 19 Daniel Jackson [ ] 20 Daniel Jackson [ ] 21 Daniel Jackson [ ] 22 Daniel Jackson [ ] 23 Daniel Jackson [ ] 24 Daniel Jackson [ ] 25 Daniel Jackson [ ] 26 Daniel Jackson [ ] 27 Daniel Jackson [ ] 28 Teal'c [ ] 29 Teal'c [ ] 30 Teal'c [ ] 31 Teal'c [ ] 32 Teal'c [ ] 33 Teal'c [ ] 34 Teal'c [ ] 35 Teal'c [ ] 36 Teal'c [ ] 37 Cameron Mitchell [ ] 38 Cameron Mitchell [ ] 39 Cameron Mitchell [ ] 40 Cameron Mitchell [ ] 41 Cameron Mitchell [ ] 42 Cameron Mitchell [ ] 43 Cameron Mitchell [ ] 44 Cameron Mitchell [ ] 45 Cameron Mitchell [ ] 46 John Sheppard [ ] 47 John Sheppard [ ] 48 John Sheppard [ ] 49 John Sheppard [ ] 50 John Sheppard [ ] 51 John Sheppard [ ] 52 John Sheppard [ ] 53 John Sheppard [ ] 54 John Sheppard [ ] 55 Rodney McKay [ ] 56 Rodney McKay [ ] 57 Rodney McKay [ ] 58 Rodney McKay [ ] 59 Rodney McKay [ ] 60 Rodney McKay [ ] 61 Rodney McKay [ ] 62 Rodney McKay [ ] 63 Rodney McKay [ ] 64 Teyla Emmagan [ ] 65 Teyla Emmagan [ ] 66 Teyla Emmagan [ ] 67 Teyla Emmagan [ ] 68 Teyla Emmagan [ ] 69 Teyla Emmagan [ ] 70 Teyla Emmagan [ ] 71 Teyla Emmagan [ ] 72 Teyla Emmagan [ ] 73 Ronon Dex [ ] 74 Ronon Dex [ ] 75 Ronon Dex [ ] 76 Ronon Dex [ ] 77 Ronon Dex [ ] 78 Ronon Dex [ ] 79 Ronon Dex [ ] 80 Ronon Dex [ ] 81 Ronon Dex [ ] 82 Vala Mal Doran [ ] 83 Vala Mal Doran [ ] 84 Vala Mal Doran [ ] 85 Dr. -

Spring 2021 Commencement Program

Spring 2021 Commencement Wednesday, May 5, 2021 Pinnacle Bank Arena Lincoln, Nebraska The mission of Southeast Community College is to empower and transform the diverse learners and communities of southeast Nebraska through accessible lifelong educational opportunities. The College provides dynamic and responsive pathways to career and technical, academic transfer and continuing education programs that contribute to personal, community and workforce development. Program Processional Presiding Mr. Bob Morgan, Vice President of Program Development/Campus Director-Beatrice National Anthem Performed by Dr. Jon Gruett, Director, SCC Chorus Welcome Dr. Paul Illich, President, Southeast Community College Commencement Address Honorable Pete Ricketts, Governor of Nebraska Certification of Candidates and Conferring of Degrees Dr. Joel Michaelis, Vice President for Instruction Ms. Nancy Seim, Outgoing 2020 Chairperson, SCC Board of Governors Ms. Kathy Boellstorff, Incoming 2021 Chairperson, SCC Board of Governors Presentation of Diplomas Academic Division Deans Recessional Commencement will be available on the College’s website at https://www.southeast.edu/graduation/ 2 Commencement Speaker Governor Pete Ricketts Governor Pete Ricketts was sworn in as Nebraska’s 40th Governor on Jan. 8, 2015, and reelected to a second term in November 2018. Over the past six years, Governor Ricketts has worked with the Legislature to deliver more than $1.5 billion in direct property tax relief, dramatically reduce the rate of state spending growth, create new workforce development programming, cut unnecessary red tape to bolster Nebraska’s business-friendly climate, and expand international markets for Nebraska’s farmers and ranchers. Thanks in part to the Governor’s leadership, Nebraska won the Governor’s Cup for the most economic development projects per capita three years in a row from 2016 to 2018. -

In the Words of Alumni

In the Words of Alumni Collin College 25th Anniversary Commemorative Anthology Why Collin College? Students attend Collin College for many reasons. Some are searching for small teacher-to-student ratios, like a private university. Some are looking for nationally renowned, award-winning professors. Some want to bolster their resumes with undergraduate research experience. Some want to take advantage of the college’s partnerships with universities and transfer with ease. Some want to take classes to gain employment in the jobs of their dreams. Like the diverse 46,000 students who attend Collin College annually, the reasons are varied and abundant. To commemorate 25 years of quality education, Collin College is shining the spotlight on some outstanding alumni and their reasons for choosing this exceptional institution of higher education. After all, what better way is there to learn about the college experience than from the experts who experienced it first hand? At Collin College, we take great pride in our students and their accomplishments. Our students are the leaders of the future, and it is an honor to touch upon a few of their many accomplishments in this publication. We look forward to the next 25 years of innovation and preeminent education and hope to add your name to the next edition of our alumni book. Cary A. Israel District President Collin College 2 ALUMNI SPOTLIGHT 3 Guillermo Ameer, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Surgery, Northwestern University “Collin College serves the community. It is an excellent school. I felt prepared to go on to the university. All of my professors were exceptional.