From the Bocas Del Toro Archipelago, Panama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ctenosaura Similis (Gray, 1831) (Squamata: Iguanidae) in Venezuela

HERPETOTROPICOS Vol. 4(1):41 Herpetological Notes / Notas Herpetologicas Copyright © 2008 Univ. Los Andes129 Printed in Venezuela. All rights reserved ISSN 1690-7930 FIRST RECORD OF THE SPINY-TAILED IGUANA CTENOSAURA SIMILIS (GRAY, 1831) (SQUAMATA: IGUANIDAE) IN VENEZUELA DIEGO FLORES 1 AND LUIS FELIPE ESQUEDA 2 1 Biology student, Escuela de Ciencias, Universidad de Oriente, Cumaná, Venezuela. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Research associate, Laboratorio de Biogeografía, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales y Ambientales, Universidad de Los Andes, Mérida 5101, Venezuela. E-mail: [email protected] The spiny-tailed iguanas of the genus Ctenosaura Wiegmann, 1828, range from coastal central Mexico to Panama, inhabiting tropical arid and moist lowlands below 500 m, along Atlantic and Pacific coasts. They comprise about 17 species (Queiroz 1987, Buckley and Axtell 1997, Köhler et al. 2000). Most species posses restricted distributions, although some, like Ctenosaura acanthura, C. hemilopha, C. pectinata and C. similis, show a wider distribution. The later has the greatest distribution, being present from the Mexican isthmus of Tehuantepec, to Colombia, including southern Mexico, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Belize, Costa Rica, Panama, Providence and San Andres islands (Smith and Taylor 1950, Smith 1972, Henderson 1973, Köhler 1995a,b). The first author spotted a population of Ctenosaura iguanas in eastern Venezuela, specifically in Anzoátegui state, at the borders of municipios Diego Bautista Urbaneja, Sotillo, and Bolívar. A collected specimen, deposited in the herpetological collection of the Laboratory of Biogeography at University of Los Andes in Mérida (museum number ULABG 7315), substantiates the distribution record. Morphological details and coloration of the specimens (Fig. -

Brongniart, 1800) in the Paris Natural History Museum

Zootaxa 4138 (2): 381–391 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4138.2.10 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:683BD945-FE55-4616-B18A-33F05B2FDD30 Rediscovery of the 220-year-old holotype of the Banded Iguana, Brachylophus fasciatus (Brongniart, 1800) in the Paris Natural History Museum IVAN INEICH1 & ROBERT N. FISHER2 1Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Sorbonne Universités, UMR 7205 (CNRS, EPHE, MNHN, UPMC; ISyEB: Institut de Systéma- tique, Évolution et Biodiversité), CP 30 (Reptiles), 25 rue Cuvier, F-75005 Paris, France. E-mail: [email protected] 2U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, San Diego Field Station, 4165 Spruance Road, Suite 200, San Diego, CA 92101-0812, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Paris Natural History Museum herpetological collection (MNHN-RA) has seven historical specimens of Brachylo- phus spp. collected late in the 18th and early in the 19th centuries. Brachylophus fasciatus was described in 1800 by Brongniart but its type was subsequently considered as lost and never present in MNHN-RA collections. We found that 220 year old holotype among existing collections, registered without any data, and we show that it was donated to MNHN- RA from Brongniart’s private collection after his death in 1847. It was registered in the catalogue of 1851 but without any data or reference to its type status. According to the coloration (uncommon midbody saddle-like dorsal banding pattern) and morphometric data given in its original description and in the subsequent examination of the type in 1802 by Daudin and in 1805 by Brongniart we found that lost holotype in the collections. -

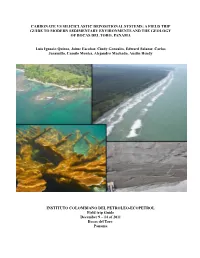

Carbonate Vs Siliciclastic Depositional Systems: a Field Trip Guide to Modern Sedimentary Environments and the Geology of Bocas Del Toro, Panama

CARBONATE VS SILICICLASTIC DEPOSITIONAL SYSTEMS: A FIELD TRIP GUIDE TO MODERN SEDIMENTARY ENVIRONMENTS AND THE GEOLOGY OF BOCAS DEL TORO, PANAMA Luis Ignacio Quiroz, Jaime Escobar, Cindy GonzalEs, Edward Salazar, Carlos Jaramillo, Camilo Montes, AlEjandro Machado, Austin HEndy INSTITUTO COLOMBIANO DEL PETROLEO-ECOPETROL FiEld trip GuidE DEcEmbEr 9 – 14 of 2011 Bocas dEl Toro Panama CARBONATE VS SILICICLASTIC DEPOSITIONAL SYSTEMS: A FIELD TRIP GUIDE TO MODERN SEDIMENTARY ENVIRONMENTS AND THE GEOLOGY OF BOCAS DEL TORO, PANAMA Luis Ignacio Quiroz University of SaskatchEwan Canada Jaime Escobar Universidad Jorge TadEo Lozano Bogotá Cindy GonzalEs Edward Salazar Carlos Jaramillo Camilo Montes AlEjandro Machado Austin HEndy Smithsonian Tropical REsEarch institute Panamá PURPOSE OF FIELD TRIP The main goal of this field trip is to study modern siliciclastic to carbonate depositional environments. The Bocas del Toro Archipelago with its protected lagoons, mangrove belts, swamps, sandy beaches and coral reef formations, provides an excellent setting to observe a wide range of modern sedimentary environments from open-water, typical Caribbean reef formations, to humid, tropical swamp environments. The research station of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, located in the middle of this archipelago, is equipped with all the laboratory space and logistical equipment to concentrate in the study of these environments. INTRODUCTION The course will take place at the Bocas del Toro Research Station. At Colon Island in Panama 's Bocas del Toro region in the Caribbean, STRI has established a site for educa- tion and research, providing scientists and students with access to an extraordinary di- versity of marine and terrestrial biota. This station is situated among areas of undisturbed forest, a remarkable coastal lagoon system, and numerous islands and reefs. -

Volcanoes & Land Iguanas

Volcanoes & Land Iguanas 1/2 Background Galapagos iguanas are thought to of arrived in the Galapagos archipelago by floating on of rafts of vegetation from the South American continent. It is estimated that a split of iguana species into Land and Marine Iguanas occurred around 10.5 million years ago. In Galapagos, 3 species of land Iguanas now exist. The Land Iguanas include: Conolophus subcristatus (found on 6 islands), Conolophus pallidus (found only on Santa Fe Island) and a third species Conolophus rosada (known for its pink colour) is found on Wolf volcano on Isabela Island. Habitat Land Iguanas are found in the drier areas of the island. Being cold- blooded, to keep warm they bask in the sun and on the volcanic rock, escaping the midday sun by finding shade under vegetation and rocks, and sleeping in burrows to conserve their body heat. Land Iguanas feed on vegetation such as fallen fruits and cactus pads and even the spines of prickly pear © David cactus. Phillips © Galapagos Conservation © Cyder Trust Volcanoes & Land Iguanas 2/2 Reproduction Between 6 and 10 years of age, male Land Iguanas become highly aggressive, fighting for the attention of the female Land Iguanas. Mating then takes place at the end of the year and eggs are usually laid between January and March (June on Fernandina!). However, in order to lay these eggs female Land Iguanas have no option but to scale to the summit of volcanoes. © Phil Herbert The Volcanic Importance Every pregnant female will need to find a patch of volcanic ash; these pockets of warm soft soil are perfect for the incubation of their eggs; however these sites are difficult to come by. -

Iguanid and Varanid CAMP 1992.Pdf

CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR IGUANIDAE AND VARANIDAE WORKING DOCUMENT December 1994 Report from the workshop held 1-3 September 1992 Edited by Rick Hudson, Allison Alberts, Susie Ellis, Onnie Byers Compiled by the Workshop Participants A Collaborative Workshop AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group SPECIES SURVIVAL COMMISSION A Publication of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, and the AZA Lizard Taxon Advisory Group. Cover Photo: Provided by Steve Reichling Hudson, R. A. Alberts, S. Ellis, 0. Byers. 1994. Conservation Assessment and Management Plan for lguanidae and Varanidae. IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group: Apple Valley, MN. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124. Send checks for US $35.00 (for printing and shipping costs) payable to CBSG; checks must be drawn on a US Banlc Funds may be wired to First Bank NA ABA No. 091000022, for credit to CBSG Account No. 1100 1210 1736. The work of the Conservation Breeding Specialist Group is made possible by generous contributions from the following members of the CBSG Institutional Conservation Council Conservators ($10,000 and above) Australasian Species Management Program Gladys Porter Zoo Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum Sponsors ($50-$249) Chicago Zoological -

Roatán Spiny-Tailed Iguana (Ctenosaura Oedirhina) Conservation Action Plan 2020–2025 Edited by Stesha A

Roatán spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura oedirhina) Conservation action plan 2020–2025 Edited by Stesha A. Pasachnik, Ashley B.C. Goode and Tandora D. Grant INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN works on biodiversity, climate change, energy, human livelihoods and greening the world economy by supporting scientific research, managing field projects all over the world, and bringing governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,400 government and NGO members and almost 15,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by around 950 staff in more than 50 countries and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org IUCN Species Programme The IUCN Species Programme supports the activities of the IUCN Species Survival Commission and individual Specialist Groups, as well as implementing global species conservation initiatives. It is an integral part of the IUCN Secretariat and is managed from IUCN’s international headquarters in Gland, Switzerland. The Species Programme includes a number of technical units covering Wildlife Trade, the Red List, Freshwater Biodiversity Assessments (all located in Cambridge, UK), and the Global Biodiversity Assessment Initiative (located in Washington DC, USA). IUCN Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of more than 9,000 experts. -

RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura Cornuta Cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789)

HUSBANDRY GUIDELINES: RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura cornuta cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789) REPTILIA: IGUANIDAE Compiler: Cameron Candy Date of Preparation: DECEMBER, 2009 Institute: Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond, NSW, Australia Course Name/Number: Certificate III in Captive Animals - 1068 Lecturers: Graeme Phipps - Jackie Salkeld - Brad Walker Husbandry Guidelines: C. c. cornuta 1 ©2009 Cameron Candy OHS WARNING RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura c. cornuta RISK CLASSIFICATION: INNOCUOUS NOTE: Adult C. c. cornuta can be reclassified as a relatively HAZARDOUS species on an individual basis. This may include breeding or territorial animals. POTENTIAL PHYSICAL HAZARDS: Bites, scratches, tail-whips: Rhinoceros Iguanas will defend themselves when threatened using bites, scratches and whipping with the tail. Generally innocuous, however, bites from adults can be severe resulting in deep lacerations. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of injury from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - Keep animal away from face and eyes at all times - Use of correct PPE such as thick gloves and employing correct and safe handling techniques when close contact is required. Conditioning animals to handling is also generally beneficial. - Collection Management; If breeding is not desired institutions can house all female or all male groups to reduce aggression - If aggressive animals are maintained protective instrument such as a broom can be used to deflect an attack OTHER HAZARDS: Zoonosis: Rhinoceros Iguanas can potentially carry the bacteria Salmonella on the surface of the skin. It can be passed to humans through contact with infected faeces or from scratches. Infection is most likely to occur when cleaning the enclosure. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of infection from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - ALWAYS wash hands with an antiseptic solution and maintain the highest standards of hygiene - It is also advisable that Tetanus vaccination is up to date in the event of a severe bite or scratch Husbandry Guidelines: C. -

Conservation Matters: CITES and New Herp Listings

Conservation matters:FEATURE | CITES CITES and new herp listings The red-tailed knobby newt (Tylototriton kweichowensis) now has a higher level of protection under CITES. Photo courtesy Milan Zygmunt/www. shutterstock.com What are the recent CITES listing changes and what do they mean for herp owners? Dr. Thomas E.J. Leuteritz from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service explains. id you know that your pet It is not just live herp may be a species of animals that are protected wildlife? Many covered by CITES, exotic reptiles and but parts and Damphibians are protected under derivatives too, such as crocodile skins CITES, also known as the Convention that feature in the on International Trade in Endangered leather trade. Plants Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. and timber are also Initiated in 1973, CITES is an included. international agreement currently Photo courtesy asharkyu/ signed by 182 countries and the www.shutterstock.com European Union (also known as responsibility of the Secretary of the How does CITES work? Parties), which regulates Interior, who has tasked the U.S. Fish Species protected by CITES are international trade in more than and Wildlife Service (USFWS) as the included in one of three lists, 35,000 wild animal and plant species, lead agency responsible for the referred to as Appendices, according including their parts, products, and Convention’s implementation. You to the degree of protection they derivatives. can help USFWS conserve these need: Appendix I includes species The aim of CITES is to ensure that species by complying with CITES threatened with extinction and international trade in specimens of and other wildlife laws to ensure provides the greatest level of wild animals and plants does not that your activities as a pet owner or protection, including restrictions on threaten their survival in the wild. -

Problem Solving in Reptile Practice Paul M

Topics in Medicine and Surgery Problem Solving in Reptile Practice Paul M. Gibbons, DVM, MS, Dip. ABVP (Avian), and Lisa A. Tell, DVM, Dip. ABVP (Avian), Dip. ACZM Abstract Problem-oriented reptile medicine is an explicit, definable process focused on the identification and resolution of a patient’s problems. This approach includes gathering case information, clearly defining the problems, making plans to address each prob- lem, and following up with the case over time. Case information and published literature serve as evidence to support clinical decisions and pathophysiological ratio- nale. This article describes the problem-solving process used to diagnose and treat a green iguana (Iguana iguana) that presents with ovostasis. © 2009 Published by Elsevier Inc. Key words: evidence-based veterinary medicine; follicular stasis; green iguana; Iguana iguana; preovulatory ovostasis; problem-oriented veterinary medicine roblem-oriented veterinary medicine is a logi- Objective evidence is quantitative and includes vital cal process directed toward the explicit iden- signs and the results of laboratory tests. A case sum- Ptification and resolution of a patient’s prob- mary is limited to information that is pertinent to lems. A complete, problem-oriented, veterinary the problems, but the problem-oriented, veterinary medical record includes evidence about the case, a medical record includes a complete record of all problem list, plans, and progress notes. Each prob- information related to the case. lem is described at the highest possible level of di- For purposes of illustration, the case described in agnostic refinement, and plans are developed to this article involved a 2.2-kg green iguana of unknown address each problem. -

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Final Report Baseline Study in Three Geographical Areas of Concentration in Mesomerica Project CAM - 2241 Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) The World Conservation Union (IUCN) Regional Office for Mesoamerica October 2001 INDEX OF CONTENT I. BACKGROUND II. OBJECTIVES III. METHODOLOGY 1. PRINCIPLES 2. ANALYSIS OF THE QUALITY OF PARTICIPATION IV. DATA ANALYSIS 1. PAZ RIVER GAC 2. SAN JUAN RIVER GAC 3. TALAMANCA – BOCAS DEL TORO GAC V. CONCLUSIONS 1. WORKING HYPOTHESES 2. PRIORITY SITES 3. PRIORITY THEMES 4. THE CONSORTIUM AS A WORKING MODEL VI. SELF-EVALUATION 1. ANALYSIS OS STUDY INDICATORS 2. ANALYSIS OF STUDY IMPACTS 3. LESSONS LEARNED MAP ANNEX Report elaborated by the Project Team: Coordinators: Jesús Cisneros y Guiselle Rodriguez Adviser: Alejandro Imbach Supervision: Enrique Lahmann I. BACKGROUND As a result an in-depth analysis on the experience of the Regional Office for Mesoamerica (ORMA) of The World Conservation Union (IUCN) during the last thirteen years in Mesoamerica, along with the analysis of impacts on regional sustainability and mobilization of IUCN membership in this context, in December 1999 ORMA presented a proposal to NORAD for a framework program aimed at the organization and consolidation of local conservation and sustainable development initiatives managed by consortia of local organizations in three geographic areas of concentration in Mesoamerica. This work modality, which promotes management of key ecosystems by local consortia, seeks to be a model for addressing the serious socio-environmental problems in Mesoamerica. NORAD expressed a favorable opinion of the proposal for a framework program and suggested that a preparatory phase be carried out to obtain basic secondary information. -

An Overlooked Pink Species of Land Iguana in the Galápagos Gabriele Gentilea,1, Anna Fabiania, Cruz Marquezb, Howard L

An overlooked pink species of land iguana in the Galápagos Gabriele Gentilea,1, Anna Fabiania, Cruz Marquezb, Howard L. Snellc, Heidi M. Snellc, Washington Tapiad, and Valerio Sbordonia aDipartimento di Biologia, Universita` Tor Vergata, 00133 Rome, Italy; bCharles Darwin Foundation, Puerto Ayora, Gala´ pagos Islands, Ecuador; cDepartment of Biology and Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; and dGalápagos National Park Service, Puerto Ayora, Gala´ pagos Islands, Ecuador Edited by Francisco J. Ayala, University of California, Irvine, CA, and approved November 11, 2008 (received for review July 2, 2008) Despite the attention given to them, the Galápagos have not yet finished offering evolutionary novelties. When Darwin visited the Galápagos, he observed both marine (Amblyrhynchus) and land (Conolophus) iguanas but did not encounter a rare pink black- striped land iguana (herein referred to as ‘‘rosada,’’ meaning ‘‘pink’’ in Spanish), which, surprisingly, remained unseen until 1986. Here, we show that substantial genetic isolation exists between the rosada and syntopic yellow forms and that the rosada is basal to extant taxonomically recognized Galápagos land igua- nas. The rosada, whose present distribution is a conundrum, is a relict lineage whose origin dates back to a period when at least some of the present-day islands had not yet formed. So far, this species is the only evidence of ancient diversification along the Galápagos land iguana lineage and documents one of the oldest events of divergence ever recorded in the Galápagos. Conservation efforts are needed to prevent this form, identified by us as a good species, from extinction. Fig. 1. Galápagos Islands. -

1 Connor Pierson Dr. William Durham Darwin, Evolution, and Galapagos

Connor Pierson Dr. William Durham Darwin, Evolution, and Galapagos 10/12/09 The Evolutionary Significance of the Pink Iguana Introduction: In 1986, Galapagos park rangers patrolling the remote summit of Volcán Wolf reported a sighting of a Galapagos land iguana with an unusual characteristic: bright pink scales. While many dismissed the anomaly as a skin condition, Dr. Gabriele Gentile from the Tor Vergata University of Rome and his team began searching for the elusive pink iguana in 2005. The next year the team (which included Howard and Heidi Snell) successfully captured, measured, and drew samples from 32 iguanas displaying the unique phenotype. The population was nicknamed, “Rosada,” the Spanish word for pink. The public was introduced to the iguana with the publication of a genetic analysis on January 13, 2009. The results published in this paper suggested that Rosada deserved recognition as a unique species due to its morphological, behavioral, and genetic differences from the two already recognized members of the genus Conolophus. On August 18, 2009 an official description of a new species, Conolophus marthae, was published in the taxonomical journal Zootaxa. While several research papers are pending, the information currently available challenges accepted theory regarding the evolution of the iguana in the Galapagos. The goals of this paper are to: (a.) introduce the reader to a distinctive new species of Galapagos Megafauna; (b.) analyze marthae’s significance in terms of current understanding of Galapagos Iguana evolution; (c.) suggest the probable route of colonization for the new species; and (d.) highlight the need for conservation and further research.1 1 Meet Rosada: Description: Conolophus marthae’s striking coloration, nuchal crest, and communicative signals distinguish the iguana from its genetic relatives, subcristatus, and pallidus.