The Agnostic in the Whirlwind: the Seven Novels of Charles Williams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Animation Auction 52A, Auction Date: 12/1/2012

26901 Agoura Road, Suite 150, Calabasas Hills, CA 91301 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Animation Auction 52A, Auction Date: 12/1/2012 LOT ITEM PRICE 4 X-MEN “OLD SOLDIERS”, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $275 FEATURING “CAPTAIN AMERICA” & “WOLVERINE”. 5 X-MEN “OLD SOLDIERS”, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $200 FEATURING “CAPTAIN AMERICA” & “WOLVERINE” FIGHTING BAD GUYS. 6 X-MEN “PHOENIX SAGA (PART 3) CRY OF THE BANSHEE”, ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL $100 AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “ERIK THE REDD”. 8 X-MEN OVERSIZED ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL AND BACKGROUND FEATURING $150 “GAMBIT”, “ROGUE”, “PROFESSOR X” & “JUBILEE”. 9 X-MEN “WEAPON X, LIES, AND VIDEOTAPE”, (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND $225 BACKGROUND FEATURING “WOLVERINE” IN WEAPON X CHAMBER. 16 X-MEN ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CEL AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “BEAST”. $100 17 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “NASTY BOYS”, $100 “SLAB” & “HAIRBAG”. 21 X-MEN (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “STORM”. $100 23 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND (2) SKETCHES FEATURING CYCLOPS’ $125 VISION OF JEAN GREY AS “PHOENIX”. 24 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “CAPTAIN $150 AMERICA” AND “WOLVERINE”. 25 X-MEN (9) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND PAN BACKGROUND FEATURING “CAPTAIN $175 AMERICA” AND “WOLVERINE”. 27 X-MEN (3) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING “STORM”, $100 “ROGUE” AND “DARKSTAR” FLYING. 31 X-MEN THE ANIMATED SERIES, (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION CELS AND BACKGROUND $100 FEATURING “PROFESSOR X” AND “2 SENTINELS”. 35 X-MEN (2) ORIGINAL PRODUCTION PAN CELS AND BACKGROUND FEATURING $100 “WOLVERINE”, “ROGUE” AND “NIGHTCRAWLER”. -

Landscapes of Korean and Korean American Biblical Interpretation

BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION AMERICAN AND KOREAN LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN International Voices in Biblical Studies In this first of its kind collection of Korean and Korean American Landscapes of Korean biblical interpretation, essays by established and emerging scholars reflect a range of historical, textual, feminist, sociological, theological, and postcolonial readings. Contributors draw upon ancient contexts and Korean American and even recent events in South Korea to shed light on familiar passages such as King Manasseh read through the Sewol Ferry Tragedy, David and Bathsheba’s narrative as the backdrop to the prohibition against Biblical Interpretation adultery, rereading the virtuous women in Proverbs 31:10–31 through a Korean woman’s experience, visualizing the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and demarcations in Galatians, and introducing the extrabiblical story of Eve and Norea, her daughter, through story (re)telling. This volume of essays introduces Korean and Korean American biblical interpretation to scholars and students interested in both traditional and contemporary contextual interpretations. Exile as Forced Migration JOHN AHN is AssociateThe Prophets Professor Speak of Hebrew on Forced Bible Migration at Howard University ThusSchool Says of Divinity.the LORD: He Essays is the on author the Former of and Latter Prophets in (2010) Honor ofand Robert coeditor R. Wilson of (2015) and (2009). Ahn Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-379-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Edited by John Ahn LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 10 LANDSCAPES OF KOREAN AND KOREAN AMERICAN BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION Edited by John Ahn Atlanta Copyright © 2019 by SBL Press All rights reserved. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

1407218430.Pdf (3.091Mb)

Welcome to 616! - A Marvel Comics fanfiction zine Table of Contents Young Avengers by Dorodraws – Young Avengers (Art) Featuring (deaged, reincarnated) Loki, America Chavez (Miss America), Tommy Shepherd (Speed), Kate Bishop (Hawkeye), Billy Kaplan (Wiccan) and Teddy Altman (Hulkling) Here In The Clouds by Brandnewfashion Here in the Clouds by Brandnewfashion - Captain Marvel “What are you doing up here?” Featuring Carol Danvers (Captain Marvel)/Peter Parker (Spider-man) Carol didn’t have to look over to see who the newcomer was. “Hi, Peter,” she greeted. Something With Wings by Elspethdixon – Avengers Said web-slinger slipped off his mask before sitting down next to the Featuring Jan van Dyne (The Wasp)/Hank Pym (Ant-man) blonde. “So.” “So?” Carol’s lips curved upwards into a smile. Smash by ScaryKrystal – Captain Marvel, She-Hulk (Art) Peter chuckled. “Are we really doing this again?” She shook her head. “I was just up here thinking.” Featuring Carol Danvers (Captain Marvel) & Jen Walters (She-Hulk) He nodded and they both looked out at the sight before them: New York always looked better at night. Manhattan was constantly bustling with Afternoon Stroll by Neveralarch – Hawkeye activity, but Queens never failed to provide a level of comfort to Peter: it Featuring Clint Barton (Hawkeye) & Kate Bishop (Hawkeye) was, after all, where he grew up. From the top of the abandoned warehouse that they were sitting on, they had a clear view of the Manhattan skyline, but By Hands and Heels by Lunik – Journey into Mystery the noises of the city were too far to be heard. Featuring Leah, (deaged, reincarnated) Loki & Thori the Hellhound Carol’s voice broke through his reverie. -

Earth-717: Avengers Vol 1 Chapter 11: Destiny As the Rogue One

Earth-717: Avengers Vol 1 Chapter 11: Destiny As the Rogue One slammed against the floor of the hangar, it crushed a large Mekkan soldier and sent his pulse rifle flying into the air. The ship slid along the metallic floor, severely scraping the armour on the underside. Once the ship came to a halt, Carol opened the back ramp, and the heroes all rushed out. There were a handful of Skrulls inside of the hangar, but they were quickly shot down by projectile attacks from Tasha, Carol and Johnny. Bruce, having taken off his clothes aside from his purple shorts, transformed into the Hulk. Herbie then floated out of the ship and started scanning the damage. “Oh, no no no no!” said Herbie. “It appears that the Rogue One has suffered from at least moderate levels of damage from the crash.” “Doesn't change what we have to do,” said Steve. “But I believe that the Repair-Bots and I can render the ship fully functional, so long as we are assisted by Doctor Richards!” said Herbie, bouncing in the air. “I will just require some time to work.” “You will have it, tiny floating automaton,” said Thor. “We have a villain to defeat.” “I'll help Herbie,” said Reed. “Make sure the Rogue One's ready for when you all get back. But you've got two objectives here. You have to destroy the ship and also retrieve the Infinity Gem, which will deactivate the Pariahs. But Veranke and the ship's reactor aren't in the same place.” Tasha shrugged. -

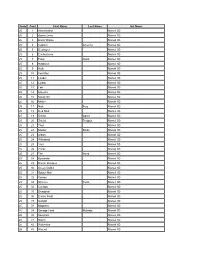

Form Card First Name Last Name Set Name 25 1 Abomination Marvel 3D

Form Card First Name Last Name Set Name 25 1 Abomination Marvel 3D 25 2 Baron Zemo Marvel 3D 25 3 Black Widow Marvel 3D 25 4 Captain America Marvel 3D 25 5 Destroyer Marvel 3D 25 6 Enchantress Marvel 3D 25 7 Frost Giant Marvel 3D 25 8 Hawkeye Marvel 3D 25 9 Hulk Marvel 3D 25 10 Iron Man Marvel 3D 25 11 Leader Marvel 3D 25 12 Lizard Marvel 3D 25 13 Loki Marvel 3D 25 14 Maestro Marvel 3D 25 15 Maria Hill Marvel 3D 25 16 Melter Marvel 3D 25 17 Nick Fury Marvel 3D 25 18 Red Skull Marvel 3D 25 19 Shield Agent Marvel 3D 25 20 Shield Trooper Marvel 3D 25 21 Thor Marvel 3D 25 22 Master Strike Marvel 3D 25 23 Ultron Marvel 3D 25 24 Whirlwind Marvel 3D 25 25 Ymir Marvel 3D 25 26 Zzzax Marvel 3D 25 27 The Hand Marvel 3D 25 28 Bystander Marvel 3D 25 29 Doctor Octopus Marvel 3D 25 30 Green Goblin Marvel 3D 25 31 Spider-Man Marvel 3D 25 32 Venom Marvel 3D 25 33 Scheme Twist Marvel 3D 25 34 Cyclops Marvel 3D 25 35 Deadpool Marvel 3D 25 36 Emma Frost Marvel 3D 25 37 Gambit Marvel 3D 25 38 Magneto Marvel 3D 25 39 Savage Land Mutates Marvel 3D 25 40 Sentinels Marvel 3D 25 41 Storm Marvel 3D 25 42 Wolverine Marvel 3D 25 43 Wound Marvel 3D 25 44 Egghead Marvel 3D 25 45 Daredevil Marvel 3D 25 46 Elektra Marvel 3D 25 47 Gladiator Marvel 3D 25 48 Punisher Marvel 3D 25 49 Blade Marvel 3D 25 50 Daredevil Marvel 3D 25 51 Elektra Marvel 3D 25 52 Ghost Rider Marvel 3D 25 53 Iron Fist Marvel 3D 25 54 Punisher Marvel 3D 25 55 Blade Marvel 3D 25 56 Daredevil Marvel 3D 25 57 Ghost Rider Marvel 3D 25 58 Iron Fist Marvel 3D 25 59 Punisher Marvel 3D 25 60 Electro Marvel -

Super Heroes V Scorsese: a Marxist Reading of Alienation and the Political Unconscious in Blockbuster Superhero Film

Kutztown University Research Commons at Kutztown University Kutztown University Masters Theses Spring 5-10-2020 SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM David Eltz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://research.library.kutztown.edu/masterstheses Part of the Film Production Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Screenwriting Commons Recommended Citation Eltz, David, "SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM" (2020). Kutztown University Masters Theses. 1. https://research.library.kutztown.edu/masterstheses/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Research Commons at Kutztown University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kutztown University Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of Research Commons at Kutztown University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUPER HEROES V SCORSESE: A MARXIST READING OF ALIENATION AND THE POLITICAL UNCONSCIOUS IN BLOCKBUSTER SUPERHERO FILM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Kutztown University of Pennsylvania Kutztown, Pennsylvania In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English by David J. Eltz October, 2020 Approval Page Approved: (Date) (Adviser) (Date) (Chair, Department of English) (Date) (Dean, Graduate Studies) Abstract As superhero blockbusters continue to dominate the theatrical landscape, critical detractors of the genre have grown in number and authority. The most influential among them, Martin Scorsese, has been quoted as referring to Marvel films as “theme parks” rather than “cinema” (his own term for auteur film). -

Whirlwind 216 Machine Manual

STANDARD EQUIPMENT: SPECIFICATIONS: • 10 HP Baldor TEFC Motor • Blade Size: 20" x 1" Bore 208/ 230/ 460/ 3/ 60 • Blade Speed: Approx. 3,165 RPM • 3 Premium V-Belts • Cycle Speed: Up to 40 I Minute • Filter, Regulator, Coalescing Filter w. Gauge • Air Cylinder: 2" x 12" • Magnetic Starter In Nema 12 Box • C.F.M . Approx. 1.96 - SCFM 12.65 with Low Voltage Controls • Table Height: 36 3/ 4 Inches • Tempered Chrome-Maly Spindle • Floor Space: 26" x 33 1/ 2 Inches • Heavy Steel Spindle Housing • Made With Pride in the U.S.A. • 4" Cast Aluminum Dust Chute • Air Supply Lock-Out CAPACITY: • 1 x 18, 2 x 16, 3 x 14, 4 x 12 OPTIONAL EQUIPMENT: • 5 x 10 and 6 x 8 • 20" A.TB. or T.C.G. Systi-Matic Blades • Spray Mist for Metal and Plastic Use • Electric Delete Credit • 15 HP Baldor TEFC Motor • 7 1/ 2 HP Single Phase Motor ELECTRICAL (Amps) Current 230 Volts 460 Volts Motor Running 26 Amps 13 Amps Service Current 50 Amps 25 Amps HEIGHT ADJUSTMENT KNOB TO ADJUST CLEARANCE BETWEEN ----MATERIAL FLOW --LUMBER AND GUARD/CLAMP (SHOULD BE 1/4 INCH) AIR CUT-OFF VALVE W. LOCK-OUT RECESSED TOP FOR OPERATOR'S HANDS 2 1/4" cast iron table top MAGNETIC STARTER IN NEMA 12 BOX LOW VOLTAGE CONTROLS ONE PIECE ACCESS DOOR WITH 1/4" STEEL PLATE: AUTOMATIC ELECTRIC ALL 4 CORNERS BENT INTERLOCK AIR HOSE FOR 4 INCH EXHAUST CLEARING CHIPS FITTING IN BACK -- MODEL 216 LEFT HAND SAW Whirlwind Inc. 4302 Shilling Way Dallas, TX USA 75237 (214) 330-9141 Fax (214) 337-9572 www.whirlwindsaws.com Whirlwind Model 216 Cut-Off Saw Owner's Manual Table of Contents ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- General Safety Rules ........................................................................................................ -

Marvel-Phile

by Steven E. Schend and Dale A. Donovan Lesser Lights II: Long-lost heroes This past summer has seen the reemer- 3-D MAN gence of some Marvel characters who Gestalt being havent been seen in action since the early 1980s. Of course, Im speaking of Adam POWERS: Warlock and Thanos, the major players in Alter ego: Hal Chandler owns a pair of the cosmic epic Infinity Gauntlet mini- special glasses that have identical red and series. Its great to see these old characters green images of a human figure on each back in their four-color glory, and Im sure lens. When Hal dons the glasses and focus- there are some great plans with these es on merging the two figures, he triggers characters forthcoming. a dimensional transfer that places him in a Nostalgia, the lowly terror of nigh- trancelike state. His mind and the two forgotten days, is alive still in The images from his glasses of his elder broth- MARVEL®-Phile in this, the second half of er, Chuck, merge into a gestalt being our quest to bring you characters from known as 3-D Man. the dusty pages of Marvel Comics past. As 3-D Man can remain active for only the aforementioned miniseries is showing three hours at a time, after which he must readers new and old, just because a char- split into his composite images and return acter hasnt been seen in a while certainly Hals mind to his body. While active, 3-D doesnt mean he lacks potential. This is the Mans brain is a composite of the minds of case with our two intrepid heroes for this both Hal and Chuck Chandler, with Chuck month, 3-D Man and the Blue Shield. -

X-Men Legacy: Salvage Pdf, Epub, Ebook

X-MEN LEGACY: SALVAGE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mike Carey,Scot Eaton,Philip Briones | 168 pages | 25 Nov 2009 | Marvel Comics | 9780785138761 | English | New York, United States X-men Legacy: Salvage PDF Book X-men Legacy: Emplate Daniel Acuna. Q: I just read about the deaths in the Uncanny Avengers, and I wanted to know if Rogue is still dead? Professor X and Magneto have extremely different views about the future of mutants, but both of them have been right on occasion. All in all though, just a bit of a let down. In with issue , the title was re-titled X-Men Legacy. Xavier trying to fix his wrongs [promises un-kept] good stuff. Charles Xavier formed a team of X-Men to bring these personalities in. In general, it seemed much more like the comic books than the others, despite it not following a major story line found in the comics. From Age of X aftermath , several personalities in Legion's mind went rogue, manifesting physically. In , Frenzy participated in a mission to stop warlords, in the process saving a girl from her abusive husband. In the aftermath of an epic battle with the Frost Giants, Thor stands trial for murder - and the verdict will fill him with rage! Mike Carey. This is also the final issue of X-Men: Legacy. Any size contribution will help keep CBH alive and full of new comics guides and content. If he's using a character, no matter how obscure, he seems to make it a point to know their history, to know how they would react to a situation, or, more specifically, another character. -

39155 369E8e52840f888dd93c

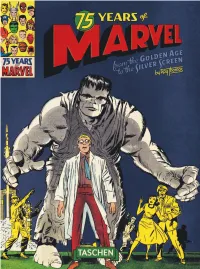

Age of Ultron (AU) (crossover Amazing Spider-Man Annual, The. Anole 698 series) 698 See Spider-Man, Amazing Spider- Ant-Man (1st) 225, 226, 229, 231, Index Agent X 679 Man Annual, The 235, 236–37, 240–41, 300, 305, Agents of S. H. I. E. L. D. (TV Amazing Spider-Man Special, The. 317, 325, 485, 501–03, 628, 681. Italic numerals refer to pages of the series) 699. See also Captain See Spider-Man, Amazing Spider- See also Giant-Man; Goliath (1st); TASCHEN book 75 Years of Marvel America, Captain America: Man Special, The Henry (Hank) Pym; Wasp, The which include images. The Winter Soldier (movie); Amazing Spider-Man, The (book). See (1st); Yellowjacket (1st) S. H. I. E. L. D. Spider-Man, Amazing Spider- Ant-Man (2nd) 581, 591, 628, 653. A Aggamon 281 Man, The (book) See also Scott Lang “Amazing Case of the Human Torch, Aja, David 685, 697 “Amazing Spider-Man, The” (comic Ant-Man (3rd) 691 The” (short story) 55 Alascia, Vince 29, 63, 68, 100 strip). See Spider-Man, “Amazing Antonioni, Michelangelo 468 A.I.M. (Advanced Idea Alcala, Alfredo 574 Spider-Man, The” (comic strip) Apache Kid 120. See also Western Mechanics) 381 Alderman, Jack 73 Amazing Spider-Man, The (movie). Gunfighters (vols. 1–2) Aaron Stack 596. See also Machine Aldrin, Edwin (“Buzz”) 453 See Spider-Man, Amazing Spider- Apache Kid, The 106 Man Alex Summers 475. See also Havok Man, The (movie) Apocalypse 654 Aaron, Jason 691, 694 Alf 649 Amazing Spider-Man, The (TV Apollo 11 453 ABC (American Broadcasting Alias (live TV version) 699 series) (1977–79). -

Marvel Comics Avengers Chronological Appearances by Bob Wolniak

Marvel Comics Avengers Chronological Appearances By Bob Wolniak ased initially on the Bob Fronczak list from Avengers Assemble and Avengers Forever websites. But unlike Mr. B Fronczak’s list (that stops about the time of Heroes Reborn) this is NOT an attempt at a Marvel continuity (harmony of Marvel titles in time within the fictional universe), but Avengers appearances in order in approx. real world release order . I define Avengers appearances as team appearances, not individual Avengers or even in some cases where several individual Avengers are together (but eventually a judgment call has to be made on some of those instances). I have included some non-Avengers appearances since they are important to a key storyline that does tie to the Avengers, but noted if they did not have a team appearance. Blue (purple for WCA & Ultimates) indicates an Avengers title , whether ongoing or limited series. I have decided that Force Works is not strictly an Avengers title, nor is Thunderbolts, Defenders or even Vision/Scarlet Witch mini- series, although each book correlates, crosses over and frequently contains guest appearances of the Avengers as a team. In those cases, the individual issues are listed. I have also decided that individual Avengers’ ongoing or limited series books are not Avengers team appearances, so I have no interest in the tedious tracking of every Captain America, Thor, Iron Man, or Hank Pym title unless they contain a team appearance or x-over . The same applies to Avengers Spotlight (largely a Hawkeye series, with other individual appearances), Captain Marvel, Ms. Marvel, Vision, Wonder Man, Hulk, She-Hulk, Black Panther, Quicksilver, Thunderstrike, War Machine, Black Widow, Sub-Mariner, Hercules, and other such books or limited series.