Family Photographs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribal Nations

Dinjii Zhuu Nation : Tribal Nations Map Gwich’in Tribal Nations Map Inuvialuit Vuntut Western Artic Innuit Deguth OurOur OwnOwn NamesNames && LocationsLocations Inuvialuit woman Draanjik Gwichyaa T'atsaot'ine Iglulingmiut Teetl'it Yellow Knives Inuit family KitlinermiutCopper Inuit Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Netsilingmiut Han Netsilik Inuit Tununirmiut Tanana Sahtú Hare Utkuhiksalingmiut Hanningajurmiut Tutchone Ihalmiut Inuit Woman & Child Akilinirmiut Kangiqliniqmiut Galyá x Kwáan Denesoline Nations: Laaxaayik Kwáan Deisleen Kwáan Chipeweyan Harvaqtuurmiut Tagish Aivilingmiut Áa Tlein Kwáan Gunaa xoo Kwáan Kaska Dena Jilkoot Kwáan Kaska Krest‘ayle kke ottine Chipeweyan band Jilkaat Kwáan Aak'w Kwáan Qaernermiut Xunaa Kwáan T'aa ku Kwáan S'aawdaan Kwáan Xutsnoowú Kwáan Kéex' Kwáan Paallirmiut Tarramiut Sheey At'iká Lingít Kwáan Shtax' héen Kwáan Des-nèdhè-kkè-nadè Nation Dene Woman Kooyu Kwáan Tahltan K'atlodeeche Ahialmiut Dene Tha' Hay River Dene Sanyaa Kwáan Slavey Sayisi Dene Siquinirmiut Takjik'aan Kwáan Lingít Men WetalTsetsauts Hinya Kwáan Nisga'a Inuit Hunter Tsimshian Kaí-theli-ke-hot!ínne Taanta'a Kwáan Dane-zaa Thlingchadinne Itivimiut Sikumiut K'yak áannii Tsek’ene Beaver Gáne-kúnan-hot!ínne Dog Rib Sekani Etthen eldili dene Gitxsan Lake Babine Wit'at Haida Gitxaala Thilanottine Hâthél-hot!inne Xàʼisla Haisla Nat'oot'en Wet'suwet'en Hoteladi Iyuw Imuun Beothuk WigWam Nuxalk Nation: Nihithawiwin Bella Coola Woodlands Cree Sikumiut man DakelhCarrier Tallheo Aatsista Mahkan, HeiltsukBella Bella Siksika chief Kwalhna Stuic Blackfoot Nation -

Tribal Engagement Strategy White Paper North Pacific Landscape Conservation Cooperative (NPLCC) Working Draft 4

Tribal Engagement Strategy White Paper North Pacific Landscape Conservation Cooperative (NPLCC) Working Draft 4 A note on language: There are many names by which to refer to Tribes and First Nations, including Tribal Nations, Tribal communities, Native Nations, Tribes, Indigenous peoples, Indigenous communities, Native peoples, and many more. To improve consistency, Tribes and First Nations will hereafter be referred to by the acronym, “T/FN.” Introduction: The NPLCC within a Changing Region _______________________________________ The NPLCC is one of 22 Landscape Conservation Cooperatives (LLCs) created by Secretarial Order No. 3289 to advance the integration of conservation science and landscape management across the North American continent and Pacific and Caribbean Islands. By taking a landscape-scale and collaborative approach to conservation, LLCs offer new ways to think about and respond to environmental stressors. The NPLCC facilitates conservation across boundaries and landscapes with many T/FN, national, and state partners, to ensure that natural and cultural resources successfully respond to a rapidly changing environment. Partly due to these tenets, the NPLCC is able to operate within two countries (the U.S. and Canada), 4 states (California, Oregon, Washington, Alaska), 1 province (British Columbia), and 1 territory (Yukon), throughout the entirety of the 2200 mile Pacific Coastal Temperate Rainforest, and include over 100 T/FN in its scope (Figure 1). We take pride in being a self-directed partnership between federal agencies, states, T/FN, non- governmental organizations, universities, and publics. At its core, the NPLCC strives to convene partners, fund projects, build capacity, and communicate information among the various actors in the region. -

Download Download

Ames, Kenneth M. and Herbert D.G. Maschner 1999 Peoples of BIBLIOGRAPHY the Northwest Coast: Their Archaeology and Prehistory. Thames and Hudson, London. Abbas, Rizwaan 2014 Monitoring of Bell-hole Tests at Amoss, Pamela T. 1993 Hair of the Dog: Unravelling Pre-contact Archaeological Site DhRs-1 (Marpole Midden), Vancouver, BC. Coast Salish Social Stratification. In American Indian Linguistics Report on file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. and Ethnography in Honor of Lawrence C. Thompson, edited by Acheson, Steven 2009 Marpole Archaeological Site (DhRs-1) Anthony Mattina and Timothy Montler, pp. 3-35. University of Management Plan—A Proposal. Report on file, British Columbia Montana Occasional Papers No. 10, Missoula. Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Andrefsky, William, Jr. 2005 Lithics: Macroscopic Approaches to Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1976 Gulf of Georgia Archaeological Analysis (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, New York. Survey: Powell River and Sechelt Regional Districts. Report on Angelbeck, Bill 2015 Survey and Excavation of Kwoiek Creek, file, British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. British Columbia. Report in preparation by Arrowstone Acheson, S. and S. Riley 1977 An Archaeological Resource Archaeology for Kanaka Bar Indian Band, and Innergex Inventory of the Northeast Gulf of Georgia Region. Report on file, Renewable Energy, Longueuil, Québec. British Columbia Archaeology Branch, Victoria. Angelbeck, Bill and Colin Grier 2012 Anarchism and the Adachi, Ken 1976 The Enemy That Never Was. McClelland & Archaeology of Anarchic Societies: Resistance to Centralization in Stewart, Toronto, Ontario. the Coast Salish Region of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Current Anthropology 53(5):547-587. Adams, Amanda 2003 Visions Cast on Stone: A Stylistic Analysis of the Petroglyphs of Gabriola Island, B.C. -

Russian American Contacts, 1917-1937: a Review Article

names of individual forts; names of M. Odivetz, and Paul J. Novgorotsev, Rydell, Robert W., All the World’s a Fair: individual ships 20(3):235-36 Visions of Empire at American “Russian American Contacts, 1917-1937: Russian Shadows on the British Northwest International Expositions, 1876-1916, A Review Article,” by Charles E. Coast of North America, 1810-1890: review, 77(2):74; In the People’s Interest: Timberlake, 61(4):217-21 A Study of Rejection of Defence A Centennial History of Montana State A Russian American Photographer in Tlingit Responsibilities, by Glynn Barratt, University, review, 85(2):70 Country: Vincent Soboleff in Alaska, by review, 75(4):186 Ryesky, Diana, “Blanche Payne, Scholar Sergei Kan, review, 105(1):43-44 “Russian Shipbuilding in the American and Teacher: Her Career in Costume Russian Expansion on the Pacific, 1641-1850, Colonies,” by Clarence L. Andrews, History,” 77(1):21-31 by F. A. Golder, review, 6(2):119-20 25(1):3-10 Ryker, Lois Valliant, With History Around Me: “A Russian Expedition to Japan in 1852,” by The Russian Withdrawal From California, by Spokane Nostalgia, review, 72(4):185 Paul E. Eckel, 34(2):159-67 Clarence John Du Four, 25(1):73 Rylatt, R. M., Surveying the Canadian Pacific: “Russian Exploration in Interior Alaska: An Russian-American convention (1824), Memoir of a Railroad Pioneer, review, Extract from the Journal of Andrei 11(2):83-88, 13(2):93-100 84(2):69 Glazunov,” by James W. VanStone, Russian-American Telegraph, Western Union Ryman, James H. T., rev. of Indian and 50(2):37-47 Extension, 72(3):137-40 White in the Northwest: A History of Russian Extension Telegraph. -

Nearshore Natural Capital Valuation Valuing the Aquatic Benefits of British Columbia’S Lower Mainland: Nearshore Natural Capital Valuation

VALUING THE AQUATIC BENEFITS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA’s LOWER MAINLAND Nearshore Natural Capital Valuation VALUING THE AQUatIC BENEFITS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA’S LOWER MAINLAND: NeaRSHORE NatURAL CAPItaL VALUatION November 2012 David Suzuki Foundation and Earth Economics By Michelle Molnar, Maya Kocian and David Batker AcknOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to acknowledge the extremely helpful contributions received during the preparation of this report. First and foremost, the authors wish to acknowledge the Sitka Foundation, who made this report possible. In addition, we would like to thank VanCity, Pacific Parklands, and Vancouver Foundation for their early and ongoing support of our natural capital work. We would like to thank Kelly Stewart (San Jose State University), Heidi Hudson (DSF), Zac Christin (EE), Lola Paulina Flores (EE) and David Marcell (EE) for their research assistance. Thanks to peer reviewers Sara Wilson (Natural Capital Research and Consulting), David Batker (EE), Jay Ritchlin (DSF) and Faisal Moola (DSF) for their advice, guidance and support in strengthening this report. Many thanks to Hugh Stimson (Geocology Research) who provided spatial data analysis and produced all of the maps within this report, and Scott Wallace (DSF) for sharing his fisheries data analysis. Copyedit and design by Nadene Rehnby handsonpublications.com Downloaded this report at davidsuzuki.org and eartheconomics.org Suite 219, 2211 West 4th Avenue 107 N. Tacoma Avenue Vancouver, B.C. V6K 4S2 Tacoma, WA 98403 T: 604.732.4228 T: 253.539.4801 E: [email protected] -

Missionization and Sḵwxwú7mesh ̱ Political Economy, 1864-1923

Missionization and Sḵwxwú7mesẖ Political Economy, 1864-1923 by Sean Wilkinson B.A. (History & Economics), Simon Fraser University, 2009 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Wilkinson 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.5 Canada (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/) Approval Name: Sean Wilkinson Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title of Thesis: Missionization and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Political Economy, 1864-1923 Examining Committee: Chair: Jay Taylor, Professor Mary-Ellen Kelm Senior Supervisor Professor J.I. Little Co-Supervisor Professor Rudy Reimer/Yumḵs Internal Examiner Assistant Professor Date Defended/Approved: 17 January 2012 ii Abstract This thesis describes the relationship between Sḵwx̱wú7mesh-speaking people of present-day North Vancouver and the Oblates of Mary Immaculate in the period between 1864 and 1923. It presents the argument that the mission that the Oblates and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh mutually founded in the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh settlement of Eslhá7an (in present-day North Vancouver) was the most significant point of cultural contact between Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and non-native people during this period. Reading Sḵwx̱wú7mesh history during this period as primarily a story of responses to colonization, it argues that some of the most important Sḵwx̱wú7mesh political and diplomatic strategies, including external strategies of resistance and accommodation as well as internal strategies of political economy, were linked to trans-cultural experiences centred at Eslhá7an. It concludes by suggesting that the emergence of Sḵwx̱wú7mesh nationalism, culminating in the establishment of the modern Squamish Nation, may have been driven by these Eslhá7an-based political strategies. -

Place-Names of the Island Halkomelem Indian People

PLACE-NAMES OF THE ISLAND HALKOMELEM INDIAN PEOPLE By DAVID LEWIS ROZEN. B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1972 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE.DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS' in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Anthropology and Sociology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July 1985 © David Lewis Rozen In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. DAVID LEWIS ROZEN Department o f ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 JULY 30, 198 5 Date /an ABSTRACT The Island Halkomelem Indian people live on the south• eastern part of Vancouver Island and on some of the southern Gulf Islands in British Columbia. A total of three hundred two (302) place-names are known to these people today, in their Coast Salish language. Each of these names is trans• cribed in a practical writing system, corresponding to the pronunciation of the Indian words by some of the thirteen elderly Island Halkomelem people who collaborated on this study. For each geographical name, information regarding its traditional and present utilization by the Indians is given. -

Connectivity in British Columbia

CONNECTIVITY IN BRITISH COLUMBIA Indigenous Communities A message from the artist In times past, it was politics and trade that kept Indigenous communities on the northwest coast connected. In the case of the Haida, being on an island, we didn’t have certain resources that the mainland people did, such as ooli- chan grease and mountain goat hair. We needed to create items that would appeal to the mainland groups we were trading with. Over time, the Haida developed specialized industries, including canoe-making, and a commer- cial art market. Though we had always made ceremonial and local trade pieces, producing art as an item of commerce on this scale helped to further refine the principles of Haida art. I see the work TELUS is doing in helping to connect Indigenous communi- ties with high-speed internet as helping to reestablish some of these ancient multinational relationships. It's enabling Indigenous communities to better communicate with one another, support one another, and to work together toward a healthier future. Iljuuwaas | Tyson Brown tysonbrown.ca A message from TELUS As part of our commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous communities, TELUS wants to support the cultural and artistic practices of Indigenous Peoples. In doing so, we must be aware of the historical role corporations have played in misappropriating Indigenous culture and art. We have an ob- ligation and responsibility to ensure that TELUS’ use of Indigenous art in our spaces is respectful of Indigenous voices. To this end, we collaborated with Tyson on the intent, context and manner of the art used within this document to ensure he retained full intellectual property and control of his creations. -

Pro Or Con? Measuring First Nations' Support Or Opposition to Oil and Gas

CEC Fact Sheet #12 | July 2020 Pro or Con? Measuring First Nations’ support or opposition to oil and gas in BC and Alberta Quantifying actual First Nations’ positions on oil and • ‘Yes’ indicates clear support in general for an oil or gas gas development development or pipelines, or for a specific project. Oil and natural gas are a substantial part of Canada’s resource • ‘No’ indicates clear opposition in general for an oil or gas economy, especially in Western Canada where, historically, development or pipelines, or to a specific project, and the majority of activity has occurred. This extraction is also absent any conflicting signals, i.e., support for some other mostly a rural activity. That reality is matched by another project. one: The rural location of many First Nations reserves. This geographic “match up” of rural First Nations and Canada’s • ‘Non-object/unclear’ indicates First Nations who in terms resource economy is not often recognized in urban Canada, known in the industry either formally do not object to a where the narrative from anti-oil and gas activists and media project and/or have withdrawn a previous objection. This stories on occasion portrays First Nations in British Columbia is not as strong as ‘Yes’ but it is also not a ‘No’ given some and Alberta as broadly anti-oil and gas development. First Nations have withdrawn previous objections to a project, i.e., withdrawing opposition to the Trans Mountain In fact, many First Nations are involved in and benefit from pipeline. oil and gas development. Two prominent examples are Fort • The “N/A” categorization is for First Nations who have not McKay in Alberta, which has a long history with the oil sands been formerly consulted on current oil or gas projects or industry, and the Haisla First Nation in British Columbia, which who do not extract oil and gas. -

2020 Staff Report

PLANNING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE Thursday, April 9, 2020 SCRD Boardroom, 1975 Field Road, Sechelt, B.C. AGENDA CALL TO ORDER 9:30 a.m. AGENDA 1. Adoption of Agenda PRESENTATIONS AND DELEGATIONS REPORTS 2. General Manager, Planning and Community Development – Planning and Annex A Community Development Department 2020 Q1 Report pp 1 - 21 Planning and Community Development Services (Voting – All) 3. Planner 1 / Senior Planner – BC Timber Sales (BCTS) Operating Plan 2020 - 2024 Annex B Regional Planning Service (Voting – All) pp 22 - 41 COMMUNICATIONS 4. Peter Robson, Pender Harbour and Area Residents Association & Dave Milligan, Annex C Pender Harbour and Area Chamber of Commerce, dated March 11, 2020. pp 42 - 43 Regarding Proposed Name Change: Madeira Park to salalus (Voting – All) 5. Peter Robson, Pender Harbour and Area Residents Association & Dave Milligan, Annex D Pender Harbour and Area Chamber of Commerce, dated March 11, 2020. pp 44 - 45 Regarding Proposed Dual Language Signs for Portions of the Sunshine Coast (Voting – All) 6. Carla Jack, Provincial Toponymist, BC Geographical Names Office, Heritage Annex E Branch, Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural pp 46 - 49 Development, dated March 26, 2020. Regarding Notice of Comment Period Extension for Proposed Name Changes within the shíshálh Nation swiya (Voting – All) NEW BUSINESS IN CAMERA ADJOURNMENT ANNEX A SUNSHINE COAST REGIONAL DISTRICT STAFF REPORT TO: Planning and Community Development Committee – April 9, 2020 AUTHOR: Ian Hall, General Manager, Planning and Community Development SUBJECT: PLANNING AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT 2020 Q1 REPORT RECOMMENDATION THAT the report titled Planning and Community Development Department 2020 Q1 Report be received. -

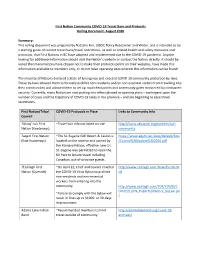

First Nation Community COVID-19 Travel Bans and Protocols Rolling Document- August 2020

First Nation Community COVID-19 Travel Bans and Protocols Rolling Document- August 2020 Summary: This rolling document was prepared by Natasha Kim, UBCIC Policy Researcher and Writer, and is intended to be a starting guide of current travel bans/travel restrictions, as well as related health and safety measures and protocols, that First Nations in BC have adopted and implemented due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Anyone looking for additional information should visit the Nation’s website or contact the Nation directly. It should be noted that many Nations have chosen not to make their protocols public on their websites, have made this information available to members only, or do not have operating sites wherein this information can be found. The majority of Nations declared a State of Emergency and enacted COVID-19 community protection by-laws. These by-laws allowed them to formally prohibit non-residents and/or non-essential visitors from travelling into their communities and allowed them to set up road checkpoints and community gates monitored by contracted security. Currently, many Nation are now putting into effect phased re-opening plans – contingent upon the number of cases and the trajectory of COVID-19 takes in the province – and are beginning to ease travel restrictions. First Nation/Tribal COVID-19 Protocols in Place Links to Community Info Council ?Akisq’ nuk First ~Travel ban info not listed on site http://www.akisqnuk.org/content/our- Nation (Kootenays) community ?aqam First Nation ~The St. Eugene Golf Resort & Casino is https://www.aqam.net/sites/default/files (East Kootenays) located on the reserve and owned by /Council%20Update%202020.pdf the Ktunaxa Nation; effective June 1st, St. -

Shishalh Responses to the Colonial Conflict (1791-Present): Resilience in the Face of Disease, Missionaries and Colonization

SHISHALH RESPONSES TO THE COLONIAL CONFLICT (1791-PRESENT): RESILIENCE IN THE FACE OF DISEASE, MISSIONARIES AND COLONIZATION by Peter S. Merchant B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1991 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) September 2012 ©Peter S. Merchant, 2012 Abstract Anthropological research regarding Coast Salish responses to the colonial conflict has held a central place in Northwest Coast anthropology for decades. Recently, it has been argued that “inordinate” attention has been given to these developments as processes of assimilation, rather than as strategic responses. This process has been viewed by the Crown as the inevitable absorption of the Coast Salish into what would become Canadian society: a result that has been facilitated by the forces of colonialism, including missionization, removal of the Coast Salish from their land, and its resources and the perceived desire of the Coast Salish to adopt Euro-Canadian practices and institutions. Through the exploration of ethnographic accounts, oral narratives, historical documents, and archaeological evidence, I illustrate how one Coast Salish people, the shishalh, have responded to and (when possible), resisted the political, social and economic stresses of the colonial conflict. I argue that shishalh resistance can be observed in the complex pattern of population redistribution from the period immediately prior to and following the smallpox epidemics of the late 18th century, and subsequent European contact and colonization. Through the use of oral narratives I situate the identified changes in population distribution within the broader framework of shishalh history, allowing for the contextualization of population restructuring in the post-contact period, not as an isolated response to the calamitous effects of contact, but more accurately as the latest in a long line of shishalh responses to changing circumstances throughout their history.