Jabliss Dissertation Deposit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TEPOZTLAN, MEXICO – 2006 12Th International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology Greg Middleton

TEPOZTLAN, MEXICO – 2006 12th International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology Greg Middleton ABSTRACT The 12th International Symposium on Vulcanospeleology was held at Tepoztlán, Mexico in July 2006. Field trips included visits to the spatter cones and vents of Los Cuescomates, Cueva del Diablo, Chimalacatepec, Iglesia Cave, Cueva del Ferrocarril, Cantona archaeological site, Alchichica Maar, El Volcancillo crater and tubes, Rio Actopan (river rafting). The author later visited some unusual volcanic caves near Colonia Moderna, northwest of Guadalajara. WELCOME TO MEXICO small band of helpers. Attendees included Arriving at Mexico City airport just before IUS Volcanic Caves Commission Chair Jan midnight on 1 July, after flying from Sydney Paul Van Der Pas (and Bep) (Netherlands), a for 25 hours (with a 3 hour stop-over in contingent from South Korea (Kyung Sik Santiago de Chile), can be slightly Woo, Kwang Choon Lee, In-Seok Son and harrowing. Then to find the last bus to others), a contingent from the Azores Cuernavaca (fare 1,100 Peso or US$10) (Paulino Costa, João C. Nunes, Paulo departed at 11:30 pm and be confronted by a Barcelos, João P. Constância and others), rather dubious-looking character offering a Marcus & Robin Gary, Diana Northup, Ken ‘taxi’ to take you there for US$160, can be Ingham and Peter Ruplinger from the USA, positively unnerving. Fortunately, with only Stephan Kempe and Horst-Volker Henschel my wallet considerably lighter, I made it to from Germany, Ed Waters and (of course) the small village of Tepoztlán, arriving at the Chris Wood from the UK, together with a Hospedaje Los Reyes at 1:45 am. -

Fun Home: a Family

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic 0 | © 2020 Hope in Box www.hopeinabox.org About Hope in a Box Hope in a Box is a national 501(c)(3) nonprofit that helps rural educators ensure every LGBTQ+ student feels safe, welcome, and included at school. We donate “Hope in a Box”: boxes of curated books featuring LGBTQ+ characters, detailed curriculum for these books, and professional development and coaching for educators. We believe that, through literature, educators can dispel stereotypes and cultivate empathy. Hope in a Box has worked with hundreds of schools across the country and, ultimately, aims to support every rural school district in the United States. Acknowledgements Special thanks to this guide’s lead author, Dr. Zachary Harvat, a high school English teacher with a PhD focusing on 20th and 21st century English literature. Additional thanks to Sara Mortensen, Josh Thompson, Daniel Tartakovsky, Sidney Hirschman, Channing Smith, and Joe English. Suggested citation: Harvat, Zachary. Curriculum Guide for Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. New York: Hope in a Box, 2020. For questions or inquiries, email our team at [email protected]. Learn more on our website, www.hopeinabox.org. Terms of use Please note that, by viewing this guide, you agree to our terms and conditions. You are licensed by Hope in a Box, Inc. to use this curriculum guide for non- commercial, educational and personal purposes only. You may download and/or copy this guide for personal or professional use, provided the copies retain all applicable copyright and trademark notices. The license granted for these materials shall be effective until July 1, 2022, unless terminated sooner by Hope in a Box, Inc. -

Passing: Intersections of Race, Gender, Class and Sexuality

Passing: Intersections of Race, Gender, Class and Sexuality Dana Christine Volk Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In ASPECT: Alliance for Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought Approved: David L. Brunsma, Committee Chair Paula M. Seniors Katrina M. Powell Disapproved: Gena E. Chandler-Smith May 17, 2017 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: passing, sexuality, gender, class, performativity, intersectionality Copyright 2017 Dana C. Volk Passing: Intersections of Race, Gender, Class, and Sexuality Dana C. Volk Abstract for scholarly and general audiences African American Literature engaged many social and racial issues that mainstream white America marginalized during the pre-civil, and post civil rights era through the use of rhetoric, setting, plot, narrative, and characterization. The use of passing fostered an outlet for many light- skinned men and women for inclusion. This trope also allowed for a closer investigation of the racial division in the United States. These issues included questions of the color line, or more specifically, how light-skinned men and women passed as white to obtain elevated economic and social status. Secondary issues in these earlier passing novels included gender and sexuality, raising questions as to whether these too existed as fixed identities in society. As such, the phenomenon of passing illustrates not just issues associated with the color line, but also social, economic, and gender structure within society. Human beings exist in a matrix, and as such, passing is not plausible if viewed solely as a process occurring within only one of these social constructs, but, rather, insists upon a viewpoint of an intersectional construct of social fluidity itself. -

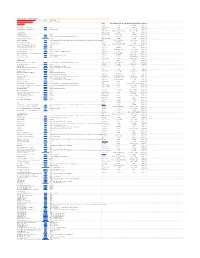

THANKSGIVING and BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always Do a Price Comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes

THANKSGIVING AND BLACK FRIDAY STORE HOURS --->> ---> ---> Always do a price comparison on Amazon Here Store Price Notes KOHL's Coupon Codes: $15SAVEBIG15 Kohl's Cash 15% for everyoff through $50 spent 11/24 through 11/25 Electronics Store Thanksgiving Day Store HoursBlack Friday Store Hours Confirmed DVD PLAYERS AAFES Closed 4:00 AM Projected RCA 10" Dual Screen Portable DVD Player Walmart $59.00 Ace Hardware Open Open Confirmed Sylvania 7" Dual-Screen Portable DVD Player Shopko $49.99 Doorbuster Apple Closed 8 am to 10 pm Projected Babies"R"Us 5 pm to 11 pm on Friday Closes at 11 pm Projected BLU-RAY PLAYERS Barnes & Noble Closed Open Confirmed LG 4K Blu-Ray Disc Player Walmart $99.00 Bass Pro Shops 8 am to 6 pm 5:00 AM Confirmed LG 4K Ultra HD 3D Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $99.99 Deals online 11/24 at 12:01am, Doors open at 5pm; Only at Best Buy Bealls 6 pm to 11 pm 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed LG 4K Ultra-HD Blu-Ray Player - Model UP870 Dell Home & Home Office$109.99 Bed Bath & Beyond Closed 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung 4K Blu-Ray Player Kohl's $129.99 Shop Doorbusters online at 12:01 a.m. (CT) Thursday 11/23, and in store Thursday at 5 p.m.* + Get $15 in Kohl's Cash for every $50 SpentBelk 4 pm to 1 am Friday 6 am to 10 pm Confirmed Samsung 4K Ultra Blu-Ray Player Shopko $169.99 Doorbuster Best Buy 5:00 PM 8:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Blu-Ray Player with Built-In WiFi BJ's $44.99 Save 11/17-11/27 Big Lots 7 am to 12 am (midnight) 6:00 AM Confirmed Samsung Streaming 3K Ultra HD Wired Blu-Ray Player Best Buy $127.99 BJ's Wholesale Club Closed 7 am -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

IN EL NORTE CON CALLE 13 AND TEGO CALDERÓN: TRACING AN ARTICULATION OF LATINO IDENTITY IN REGUETÓN By CYNTHIA MENDOZA A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Cynthia Mendoza 2 To Emilio Aguirre, de quien herede el amor a los libros To Mami and Sis, for your patience in loving me 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank G, for carrying me through my years of school. I thank my mother, Rosalpina Aguirre, for always being my biggest supporter even when not understanding. I thank my sister, Shirley Mendoza-Castilla, for letting me know when I am being a drama queen, providing comedic relief in my life, and for being a one-of-a-kind sister. I thank my aunt Lucrecia Aguirre, for worrying about me and calling to yell at me. I thank my Gainesville family: Priscilla, Andres, Ximena, and Cindy, for providing support and comfort but also the necessary breaks from school. I want to thank Rodney for being just one phone call away. I thank my committee: Dr. Horton-Stallings and Dr. Marsha Bryant, for their support and encouragement since my undergraduate years; without their guidance, I cannot imagine making it this far. I thank Dr. Efraín Barradas, for his support and guidance in understanding and clarifying my thesis subject. I thank my cousins Katia and Ana Gabriela, for reminding why is it that I do what I do. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...............................................................................................................4 -

Batman Arkham Asylum Free

FREE BATMAN ARKHAM ASYLUM PDF Dave McKean,Grant Morrison | 224 pages | 18 Nov 2014 | DC Comics | 9781401251246 | English | United States Arkham Asylum - Wikipedia Arkham Asylum first appeared in Batman Arkham Asylum Oct. Arkham Asylum serves as a psychiatric hospital for the Gotham City area, housing patients who are criminally Batman Arkham Asylum. Arkham's high-profile patients are often members of Batman's rogues gallery. Located in Gotham CityArkham Batman Arkham Asylum is where Batman's foes who are considered to be mentally ill are brought as patients other foes are incarcerated at Blackgate Penitentiary. Although it has had numerous administrators, some comic books have featured Jeremiah Arkham. Inspired by the works of H. Lovecraftand in particular his fictional city of Arkham, Massachusetts[2] [3] the asylum was introduced by Dennis O'Neil and Irv Novick and first appeared in Batman October ; much of its back-story was created by Len Wein during the s. Arkham Asylum has a poor security record and high recidivism rate, at least with regard to the high-profile cases—patients, such as Batman Arkham Asylum Joker, are frequently shown escaping at will—and those who are considered to no longer be mentally unwell and discharged tend to re-offend. Furthermore, several staff members, including its founder, Dr. Amadeus Arkhamand his nephew, director Dr. Jeremiah Arkhamas well as staff members Dr. Harleen QuinzelLyle Bolton and, in some incarnations, Dr. Jonathan Crane and Professor Hugo Strangehave become mentally unwell. In addition, prisoners with unusual medical conditions that prevent them from staying in a regular prison are housed in Arkham. -

Journal of Lesbian Studies Special Issue on Lesbians and Comics

Journal of Lesbian Studies Special Issue on Lesbians and Comics Edited by Michelle Ann Abate, Karly Marie Grice, and Christine N. Stamper In examples ranging from Trina Robbins’s “Sandy Comes Out” in the first issue of Wimmen’s Comix (1972) and Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For series (1986 – 2005) to Diane DiMassa's Hothead Paisan (1991 – 1996) and the recent reboot of DC’s Batwoman (2006 - present), comics have been an important locus of lesbian identity, community, and politics for generations. Accordingly, this special issue will explore the intersection of lesbians and comics. What role have comics played in the cultural construction, social visibility, and political advocacy of same-sex female attraction and identity? Likewise, how have these features changed over time? What is the relationship between lesbian comics and queer comics? In what ways does lesbian identity differ from queer female identity in comics, and what role has the medium played in establishing this distinction as well as blurring, reinforcing, or policing it? Discussions of comics from all eras, countries, and styles are welcome. Likewise, we encourage examinations of comics from not simply literary, artistic, and visual perspectives, but from social, economic, educational, and political angles as well. Possible topics include, but are not limited to: Comics as a locus of representation for lesbian identity, community, and sexuality Analysis of titles featuring lesbian plots, characters, and themes, such as Ariel Schrag’s The High School Chronicles strips, -

Dark Knight's War on Terrorism

The Dark Knight's War on Terrorism John Ip* I. INTRODUCTION Terrorism and counterterrorism have long been staple subjects of Hollywood films. This trend has only become more pronounced since the attacks of September 11, 2001, and the resulting increase in public concern and interest about these subjects.! In a short period of time, Hollywood action films and thrillers have come to reflect the cultural zeitgeist of the war on terrorism. 2 This essay discusses one of those films, Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight,3 as an allegorical story about post-9/11 counterterrorism. Being an allegory, the film is considerably subtler than legendary comic book creator Frank Miller's proposed story about Batman defending Gotham City from terrorist attacks by al Qaeda.4 Nevertheless, the parallels between the film's depiction of counterterrorism and the war on terrorism are unmistakable. While a blockbuster film is not the most obvious starting point for a discussion about the war on terrorism, it is nonetheless instructive to see what The Dark Knight, a piece of popular culture, has to say about law and justice in the context of post-9/11 terrorism and counterterrorism.5 Indeed, as scholars of law and popular culture such as Lawrence Friedman have argued, popular culture has something to tell us about society's norms: "In society, there are general ideas about right and wrong, about good and bad; these are templates out of which legal norms are cut, and they are also ingredients from which song- and script-writers craft their themes and plots."6 Faculty of Law, University of Auckland. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

Two Per Cent of What?: Constructing a Corpus of Typical American Comic Books Bart Beaty, Nick Sousanis, and Benjamin Woo This Is

Two Per Cent of What?: Constructing a Corpus of Typical American Comic Books Bart Beaty, Nick Sousanis, and Benjamin Woo This is an uncorrected pre-print version of this paper. Please consult the final version for all citations: Beaty, Bart, Nick Sousanis, and Benjamin Woo. “Two Per Cent of What?: Constructing a Corpus of Typical American Comics Books.” In Wildfeuer, Janina, Alexander Dunst, Jochen Laubrock (Eds.). Empirical Comics Research: Digital, Multimodal, and Cognitive Methods (27-42). Routledge, 2018. 1 “One of the most significant effects of the transformations undergone by the different genres is the transformation of their transformation-time. The model of permanent revolution which was valid for poetry tends to extend to the novel and even the theatre […], so that these two genres are also structured by the fundamental opposition between the sub-field of “mass production” and the endlessly changing sub-field of restricted production. It follows that the opposition between the genres tends to decline, as there develops within each of them an “autonomous” sub- field, springing from the opposition between a field of restricted production and a field of mass production.” - Pierre Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production” 1. Introduction Although it is asserted more strongly that it is demonstrated in his writing, Pierre Bourdieu’s notion of a “transformation of transformation-time” fruitfully points to an understanding of cultural change that seems both commonsensical and highly elusive. In the field of comic books, it is almost intuitively logical to suggest that there are stylistic, narrative, and generic conventions that are more closely tied to historical periodization than to the particularities of individual creators, titles, or publishers. -

Witnessing Fukushima Secondhand

Benoît Crucifix, ‘Witnessing Fukushima Secondhand: Collage, THE COMICS GRID Archive and Travelling Memory in Jacques Ristorcelli’s Journal of comics scholarship Les Écrans’ (2016) 6(1): 4 The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16995/cg.73 RESEARCH Witnessing Fukushima Secondhand: Collage, Archive and Travelling Memory in Jacques Ristorcelli’s Les Écrans Benoît Crucifix1 1 Université de Liège/Université catholique de Louvain, Belgium [email protected] Cultural memory in comics studies mostly seems to revolve around nonfic- tional graphic novels tackling major historical events. Drawing on recent trends in cultural memory studies, this paper focuses on Jacques Ristor- celli‘s Les Écrans (2014) as an experimental counterpoint where memory is animated by the author’s use of collage. Delving into an ‘archive’ of heterogeneous elements, Les Écrans borrows from old war comics in a way that reflexively constructs a discourse on the past of the medium and its memory. Through the analysis of Ristorcelli’s book, this paper highlights how collage can function in comics as a work of memory that reaches back to appropriative practices common to both readers and fine artists. Keywords: appropriation; archive; collage; cultural memory; Jacques Ristorcelli In a ‘videosphere,’ as Debray (2000) termed our media age riddled with screens and digital images, anxieties about the dangers and delusions of the image have grown all the more widespread, as concerns raise about our critical abilities to read and decode them. Influential voices as Hirsch (2004) and Chute (2008) have suggested that graphic narratives, partly because of their word-and-image hybridity, are par- ticularly suited to school their readers into new ways of navigating this videosphere, of reading the historical moment and the ‘collateral damage’ of its mass-mediation (Hirsch 2004: 1213). -

Author Alison Bechdel's Acceptance of Her Homosexual Iden

Acceptance versus Suppression: Homosexuality in the “Fun Home” Author Alison Bechdel’s acceptance of her homosexual identity, as illustrated in Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, is a more fluid experience than her father’s similar realization. Their unique first experiences with their sexuality play a role in their definitions of homosexuality. Both also spend their emerging adulthood years in different settings: Alison in a college setting and Bruce in a small town. Literature is a common bond between the two throughout their relationship, but affects each in different ways, particularly in reference to understanding their sexuality. The immense distinctions in their encounters and experiences involving their homosexuality ultimately shaped their development: Alison into a woman accepting of her identity and Bruce into a man suppressing his. Each character’s first experience with homosexuality differed in everything from their age at the time to the type of person with whom it occurred. Bruce had his first encounter when he was young with a worker at his family farm. Here, he describes it as “nice”, rather than a traumatizing encounter (Bechdel 220). Inspecting the drawings, his face tells a different story. Because of how casually he refers to it, he still seems unwilling to fully admit to his gratification of the experience, even if it was something he enjoyed. When Alison’s mother first informs Alison that her dad is also homosexual, she blames it on this experience (58). 1 Her mother stutters, showing her acknowledgement that her husband’s encounter with the farm hand was not molestation, but something he wanted and most likely enjoyed.