Transcript of Interview with Lala Rukh, 2009 (Part 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poem of Faiz Ahmed Faiz “Loneliness” Translated by Mahmood Jamal: a Stylistics Study

GSJ: Volume 9, Issue 7, July 2021 ISSN 2320-9186 3558 GSJ: Volume 9, Issue 7, July 2021, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com Poem of Faiz Ahmed Faiz “Loneliness” translated by Mahmood Jamal: A Stylistics Study *Muhammad Haroon Jakhrani (M.phil English at Institute of Southern Punjab Multan, Pakistan) Email: [email protected] Ph: +923450147151 Abstract: The purpose of this study is to provide Faiz Ahmed Faiz's stylistic study on loneliness, which was translated by Mahmood Jamal. The current research will disclose the poem's primary topics and notions. As a result, the researcher's attention would be on graph logical, lexical, semantics, and figures of speech in order to attain this purpose. Key words: translation, stylistics, style, lexical, graphology, semantics, figures of speech Introduction: Faiz Ahmed Faiz is unquestionably one of the brightest Urdu poets of modern century. Matter of fact, he had a singular voice that shook a nation's soul and uplifted the spirit of poetry in his period. There are poets with more literary merit who are not well-known, and there are poets who are well-known but lack literary merit. Faiz Ahmed Faiz was one of those rare intellectuals who was both well-known and well-received by the critics. This occurs infrequently, but it does occur in elite writers at various periods. Faiz Ahmed Faiz rose to prominence as a poet in the 1950s, and for a generation of Pakistanis, he became such a beacon of romance and revolutionary. His lyrics soaked into an entire culture and expresses the desires and ambitions of thousands by vocalists like Mehdi Hassan, Iqbal Bano, and Noor Jahan, not to mention Nayyara Noor. -

Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.No Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID

Details of Employees (Pending Biometric) Non-Verified Unknown District S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID Women Medical 1 Dr. Afroze Khan Muhammad Chang (NULL) (NULL) Officer Women Medical 2 Dr. Shahnaz Abdullah Memon (NULL) 4130137928800 (NULL) Officer Muhammad Yaqoob Lund Women Medical 3 Dr. Saira Parveen (NULL) 4130379142244 (NULL) Baloch Officer Women Medical 4 Dr. Sharmeen Ashfaque Ashfaque Ahmed (NULL) 4140586538660 (NULL) Officer 5 Sameera Haider Ali Haider Jalbani Counselor (NULL) 4230152125668 214483656 Women Medical 6 Dr. Kanwal Gul Pirbho Mal Tarbani (NULL) 4320303150438 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 7 Dr. Saiqa Parveen Nizamuddin Khoso (NULL) 432068166602- (NULL) Officer Tertiary Care Manager 8 Faiz Ali Mangi Muhammad Achar (NULL) 4330213367251 214483652 /Medical Officer Women Medical 9 Dr. Kaneez Kalsoom Ghulam Hussain Dobal (NULL) 4410190742003 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 10 Dr. Sheeza Khan Muhammad Shahid Khan Pathan (NULL) 4420445717090 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 11 Dr. Rukhsana Khatoon Muhammad Alam Metlo (NULL) 4520492840334 (NULL) Officer Women Medical 12 Dr. Andleeb Liaqat Ali Arain (NULL) 454023016900 (NULL) Officer Badin S.no Employee Name Father Name Designation Institution Name CNIC Personel ID 1 MUHAMMAD SHAFI ABDULLAH WATER MAN unknown 1350353237435 10334485 2 IQBAL AHMED MEMON ALI MUHMMED MEMON Senior Medical Officer unknown 4110101265785 10337156 3 MENZOOR AHMED ABDUL REHAMN MEMON Medical Officer unknown 4110101388725 10337138 4 ALLAH BUX ABDUL KARIM Dispensor unknown -

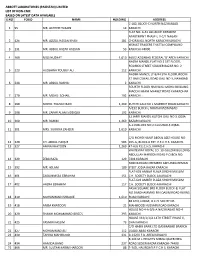

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of Non CNIC Shareholders Final Dividend for the Year Ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR

Abbott Laboratories (Pak) Ltd. List of non CNIC shareholders Final Dividend For the year ended Dec 31, 2015 SNO WARRANT_NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS 1 510004 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 2 510007 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. 3 510008 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND KARACHI-74000. 4 510009 164 MR. MOHD. RAFIQ 1269 C/O TAJ TRADING CO. O.T. 8/81, KAGZI BAZAR KARACHI. 5 510010 169 MISS NUZHAT 1610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI 6 510011 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 KARACHI 7 510012 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD KARACHI 8 510015 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR KARACHI 9 510017 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI 10 510019 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD KARACHI 11 510020 300 MR. RAHIM 1269 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA BAZAR KARACHI 12 510021 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1610 A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL KARACHI 13 510022 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. -

Koppal-Davanagere-Tumkur- Approved List Bidaai-201920

Bidaai-201920 Koppal-Davanagere-Tumkur- Approved List REG NAME OF THE Name of the Account SL.NO. TALUK Holder Amount NO BENEFICIARY Father/Mother 1 79/2018-19 Gangavthi KHAJABNI KHAJABANI 25000 2 92/208-19 KOPPAL YASMEEN SHAHAJADIBI 25000 3 128/18-19 KOPPAL ASMA BEGUM SHAHIDA BEGUM 25000 4 82/18-19 KOPPAL MABOOBI RAMJA BEE 25000 5 76/18-19 KOPPAL RIZVANA KHAM SALIMA BEGAM 25000 6 78/18-19 KOPPAL RESHMA MODINA BI 25000 7 88/18-19 KOPPAL BIBI ASHIYA BEGUM BIBI BEGUM K HABEEBA 25000 8 83/19-19 KOPPAL MARDAN BEE IMAMSAB 25000 9 99/18-19 KOPPAL AYISHA BANU NILOFAR 25000 10 107/18-19 KOPPAL YASMEEN BANU BI 25000 11 129/18-19 KOPPAL CHAND BI IMAM SAB 25000 12 122/18-19 KOPPAL TASLEEM BANU SHAKILA BANU 25000 13 85/18-19 KOPPAL RUKSANA PIRAMBI 25000 14 101/18-19 KOPPAL YASMEEN BANU JAIRABEE GUDDADAR 25000 15 115/18-19 KOPPAL SANIHA TABASUM SANIHA TABASSUM 25000 16 127/18-19 KOPPAL HEENA TAZ BABUSAB DAMBAL 25000 17 96/18-19 KOPPAL RUBIYA BEGUM SHAHAJAD BEGUM 25000 18 108/18-19 KOPPAL SABEEHA BANU KHAJABANI MAJEERA 25000 19 89/2018-19 KOPPAL RUKSHANA BEGUM Rukshana Begum 25000 20 120/2018-19 KOPPAL NISHAMA FATHIMA Raheema Begum 25000 21 136/2018-19 KOPPAL Ashabee KHAJA BEE 25000 MAMTAJBI BASHUSAB 22 80/2018-19 KOPPAL Sabina Begum 25000 VALIKAR 23 106/2018-19 KOPPAL Yasmeen Kasim Sab 25000 24 79/2018-19 KOPPAL Mohaseena Nafees Hafiza bi 25000 25 84/2018-19 KOPPAL Navina Begum Mabusab Yenni 25000 26 91/2018-19 KOPPAL Shamina Begum Fathimabi 25000 27 132/2018-19 KOPPAL Yasmeen Arifa Begum 25000 28 121/2018-19 KOPPAL Parveen Mamataj Begum 25000 29 134/2018-19 -

Newsletter July 2018 | Issue 25 | Half Yearly

NEWSLETTER JULY 2018 | ISSUE 25 | HALF YEARLY Celebrating 35 Years of Excellence in Mental Health Care CEO’s Message I am pleased to present the Newsletter of Karwan- free of cost treatment, has set an example for many to follow. e-Hayat with great happiness. This year, we are The last six months have been very busy, crowded as they were with celebrating Karwan’s 35 years of excellence in a number of events, workshops, fundraisers, awareness sessions, mental health care. Karwan-e-Hayat has been at the zakat campaign and most of all the 1st International Conference on forefront in redefining and introducing innovative Psychosocial & Psychiatric Rehabilitation, which was a huge success. practices through which mental healthcare is I am thankful to all the supporters, employees and friends of Karwan provided to the people of Pakistan. Our successful without whom this success would not have been possible. I wish you all model of being a network of paperless hospitals, providing happy reading and a prosperous year ahead and hope for your continued indiscriminate quality mental healthcare and above all providing 90% support. Thank you Zaheeruddin Babar Yadain Karwan’s Annual Fundraising Event This year Karwan’s annual Fundraiser was on 17th & 18th February 2018, at The Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, where renowned artist, Humaira Channa, performed on two magical musical evenings of songs and ghazal. She sang ghazals of legends like Madam Noor Jehan, Mehdi Hasan, Farida Khanum, Ahmed Rushdi and many more. The show was hosted by well-known music composer, artist and friend of Karwan, Mr. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

UBL Employee Pension Fund Trust

UBL Employee Pension Fund Trust Employees Retrenched in 1997 on Pension Fund Scheme List of complete retrenched employees in terms of Supreme Court Orders; Column1 EMPNO EMPLOYEE_NAME 1 113148 SYED ZAFAR ALI 2 113290 IQBAL PERVEZ MIRZA 3 113333 MIAN AHSAN HABIB 4 113388 MUHAMMAD LATIF KHAN 5 113397 S M PARWEZ AKHTAR 6 113449 MUHAMMAD QAYYUM MIRZA 7 113689 MUHAMMAD YUNUS 8 113865 SAADAT ALI 9 113883 SHAH BEHRAM QURESHI 10 113908 CH NAZIR AHMED 11 114361 MUHAMMAD AFZAL 12 114662 MOHAMMAD ASLAM 13 114811 JAMIL UR REHMAN 14 114884 MOHAMMAD ASHRAF JANJUA 15 114909 ANWAR HUSSAIN 16 114945 ZAMIR AHMED 17 114963 MUHAMMAD QUDDUS HASAN SIDDIQUI 18 115016 NASIM AHMED 19 115131 MUHAMMAD HANIF 20 115326 ABDUL QADIR AWAN 21 115423 MUHAMMAD ASHFAQUE 22 115654 ANSAR AHMED 23 115779 MUHAMMED SIDDIQUE ABA ALI 24 115788 WASIM AKHTAR GHANI 25 115867 ABOOBAKER 26 115919 MIRZA AFLAQ BEG 27 116211 SALEEM A BANA 28 116239 MUHAMMAD ISMAIL KHAN AFRIDI 29 116372 GHULAM HUSSAIN 30 116789 TURAB ALI A FRAMEWALA 31 116798 GHULAM AKBAR 32 116804 MUHAMMAD AMIN 33 116877 MUHAMMAD AMIN KHAN 34 117009 MUHAMMAD YOUSUF BAKKER 35 117188 MUHAMMAD IQBAL 36 117197 ALEXANDER MATHEWS 37 117452 KAMALUDDIN 38 117513 S SHAH NAWAZ ZIA 39 117586 ABDUL RAZZAQ TAI 40 117896 BADRUDDIN 41 117984 GUL ALAM KHAN Column1 EMPNO EMPLOYEE_NAME 42 118037 NASEER AHMED 43 118426 MANNAN AHMED 44 118648 S ANJUM HUSSAIN NAQVI 45 119010 MUHAMMAD YAQOOB 46 119199 ZAFAR IQBAL BHATTI 47 119223 RAIS AKHTAR 48 119375 QADRI MUHAMMAD SHAFI 49 119481 MUHAMMED IQBAL 50 119746 ABDUL QAYYUM 51 119807 IQBAL DAYALA -

Old-City Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts

Bāzyāft-31 (Jul-Dec 2017) Urdu Department, Punjab University, Lahore 21 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Amjad Parvez ABSTRACT: Lahore has been known as a crucible of diversified cultures owing to its nature of being a trade center, as well as being situated on the path to the capital city Delhi. Both consumers and invaders, played their part in the acculturation of this city from ancient times to the modern era.This research paperinvestigates the existing as well as the vanishing popular culture of the Old-city Lahore. The cuisine, crafts, kites, music, painting and couture of Lahore advocate the assimilation of varied tastes, patterns and colours, with dissimilar origins, within the narrow streets of the Old- city. This document will cover the food, vendors, artisans, artists and the red-light area, not only according to their locations and existence, butin terms of cultural relations too.The paper also covers the distinct standing of Lahore in the South Asia and its popularity among, not only its inhabitants, but also those who ever visited Lahore. Introduction The Old City of Lahore is characterized by the diversity of cultures that is due tovarious invaders and ruling dynasties over the centuries. The narrow streets, dabbed patches of light andunmatched cuisine add to the colours, fragrance and panorama of this unique place. 22 Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts Figure 1. “Old-city Lahore Street” (2015) By Amjad Parvez Digital Photograph Personal Collection Inside the Old-city Lahore, one may come the steadiness and stationary quality of time, or even one could feel to have been travelled backward in the two or three centuries when things were hand-made, and the culture was non-metropolitan. -

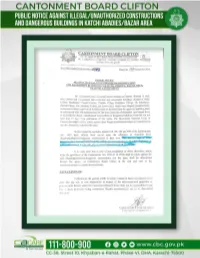

Public Notice Against Illegal / Unauthorized Constructions

CANTONMENT BOARD CLIFTON CC-38, Street 10, Kh-e-Rahat, Phase-VI, DHA, Karachi-75500 Ph. # 35847831-2, 35348774-5, 35850403, 35348784, Fax 5847835 Website: www.cbc.gov.pk _____________________________________ No. CBC/Lands/Publication/012/ Dated the 16 December 2020. PUBLIC NOTICE AGAINST ILLEGAL/UNAUTHORIZED CONSTRUCTION AND DANGEROUS BUILDINGS IN KATCHI ABADIES/BAZAR AREA CLIFTON CANTONMENT All concerned/owners/occupants/lessees/tenants are hereby directed in their own interest and convenience that residential and commercial buildings situated at Delhi Colony, Madniabad, Punjab Colony, Chandio Village, Bukhshan Village, Ch. Khaliq-uz-Zaman Colony, Pak Jamhoria Colony and Lower Gizri, which were illegally/unauthorizedly constructed without approval of building plans or deviated from the approved building plans or constructed with sub- standard material and may cause loss of properties and human lives, to demolish the illegal, unauthorized constructions or dangerous buildings forthwith but not later than 15 days from publication of this notice. The Honourable Supreme Court of Pakistan has taken serious notice against these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions and also directed to demolish the same. In this regard the requisites notices U/S 126, 185 and 256 of the Cantonments Act, 1924 have already been served upon the offenders to demolish these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions at their own. The details of such properties are as under:- DEHLI COLONY NO.01 S. Property Name of present owner Violation/ status of Name of original Lessee No. No. as per record of CBC illegal construction 1 A-01/01 Mr. Noor Bat Khan Mrs. Abida Noor Ground + 7th Floor 2 A-01/02 Mr. -

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

THE RECORD NEWS ======The Journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------S.I.R.C

THE RECORD NEWS ============================================================= The journal of the ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ ------------------------------------------------------------------------ ISSN 0971-7942 Volume: Annual - TRN 2011 ------------------------------------------------------------------------ S.I.R.C. Units: Mumbai, Pune, Solapur, Nanded and Amravati ============================================================= Feature Articles Music of Mughal-e-Azam. Bai, Begum, Dasi, Devi and Jan’s on gramophone records, Spiritual message of Gandhiji, Lyricist Gandhiji, Parlophon records in Sri Lanka, The First playback singer in Malayalam Films 1 ‘The Record News’ Annual magazine of ‘Society of Indian Record Collectors’ [SIRC] {Established: 1990} -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- President Narayan Mulani Hon. Secretary Suresh Chandvankar Hon. Treasurer Krishnaraj Merchant ==================================================== Patron Member: Mr. Michael S. Kinnear, Australia -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Honorary Members V. A. K. Ranga Rao, Chennai Harmandir Singh Hamraz, Kanpur -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Membership Fee: [Inclusive of the journal subscription] Annual Membership Rs. 1,000 Overseas US $ 100 Life Membership Rs. 10,000 Overseas US $ 1,000 Annual term: July to June Members joining anytime during the year [July-June] pay the full