Insights from the Beatitudes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Light of the World Matthew 5:14-16

The Light of the World Matthew 5:14-16 You are the light of the world. A city on a hill cannot be hidden. Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bowl. Instead, they put it on its stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house. - Matthew 5:14-15 Jesus says His followers are the light of the world. This week, find out how you can shine God's amazing light into the world around you. Pray each day to talk to God about what you are learning. Day #2 continued: The Light John 1:6-9 describes Jesus' cousin John the Have you ever thought about the sun? Now Baptist: "A man came who was sent from God. His there's a light! Scientists tell us that the sun is a name was John. He came to give witness about ball of burning gases that is 109 times larger than that light. He gave witness so that all people could the earth! That is like a basketball compared to believe. John himself was not the light. He came the head of a pin. When the sun is shining, it lights only as a witness to the light. The true light that up half of our planet at a time. What does it mean gives light to every man was coming into the world." when Jesus tells us to shine? What does it mean to be a witness? A witness in In the same way, let your light shine in front of a courtroom is one who has seen something and others. -

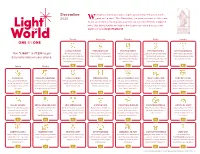

Light the World 2020 Prompt Calendar US Version

December hen Jesus Christ was born, angels proclaimed, “Peace on earth, 2020 good will to men.” This December, the promise remains the same. WAs we serve others the way Jesus served, we can end 2020 on a hopeful note. Use this calendar for inspiration as you use every day as a new opportunity to #LightTheWorld. Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday GIVING TUESDAY HERO HIGHLIGHT PEACE ON EARTH THE CHRIST CHILD PAY IT BACKWARDS Text “LIGHT” to 71234 to get Give like Jesus did. Make a Who represents Christlike love Help others feel peace as Jesus Jesus’s birth brought hope. Watch Show gratitude like Jesus did. donation to charity, or volunteer to you? Highlight them on social did. Post a picture or video to The Christ Child, screenshot a Think of someone who served daily reminders on your phone. with a local nonprofit and post a media. social media that brings you moment that gives you hope, and you and return the favor. link so others can participate. peace and calm. share why on social media. Sunday Monday 01 02 03 04 05 FAST RELIEF SIGNS OF CHRISTMAS HEALTH CARING WORDS OF LOVE LIGHT THE FAMILY TREE TREATS TIMES TWO SHOP WITH CARE Fast as Jesus did. Go without a Lift others like Jesus did. Decorate Show appreciation for health-care Be mindful of those you love, like Like Jesus, you can honor those Share as Jesus did. Make two Jesus cared for His community. meal or two and donate the cost a neighbor’s door with Christmas workers. Share a post inviting Jesus was. -

7 LAST WORDS of CHRIST a Good Friday Tenebrae Service

7 LAST WORDS OF CHRIST A Good Friday Tenebrae Service ABOUT THIS SERVICE: This service focuses on the Seven Last Words of Christ and is patterned after the ancient office of Tenebrae. The word "Tenebrae" means darkness. The purpose of the service is to impress upon us the terrible reality of sin, which caused our Savior to die for us. The service begins with the stripping of the altar. As Jesus was stripped for crucifixion, so our altar and chancel are laid bare in remembrance of His great suffering. As the service continues, you will hear your Savior speak His last words, which are recorded for us in the four Gospels. Each reading is followed by a brief devotion, silence, prayer, and a hymn. After each of the 7 Words is read, a candle is extinguished, causing the chancel to become increasingly darkened. By this we are reminded of the darkness that covered the earth at the time our Lord’s crucifixion. It also serves as a reminder of the spiritual darkness that would exist had the Light of the world not come. The exit of the Christ Candle, near the close of the service, signifies Christ's death and burial. Then there is a loud noise, symbolizing the closing of the tomb. The Christ Candle will reappear at the Easter Festival Service in celebration of the resurrection. SILENT PRAYER BEFORE WORSHIP: Lord Jesus Christ, as I meditate in this service on Your death for me, let those final sentences which You spoke from the cross impart a personal blessing, that I may both worship in spirit and truth and be moved to sacrifice my whole life as an offering to You. -

Catechesis of the Good Shepherd Summary of Presentations

Catechesis of the Good Shepherd Summary of Presentations “Help Me Fall in Love with God” The philosophy of the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd program is that even very young children have a religious life. God is present to them in their deepest being and they are capable of developing both a conscious and intimate relationship with God. We provide materials based on age-appropriate Scripture passages and liturgical signs that nurture their relationship with God. The program balances exposure to our liturgy and the richness of our communal sacramental life with reading the Bible. Our program begins with presenting the New Testament to the children because it is the foundation of our faith. The youngest learn about Jesus and the beauty and wonder of the Kingdom of God through carefully chosen Bible verses that foster a deep love for Jesus. As they grow older they are encouraged to think about their personal responsibility to maintain this relationship with God and their social responsibility in the world. The oldest group studies the Old Testament in great detail and continues to deepen their understanding of the liturgy. They plan worship services and begin community service. Each presentation has specific materials designed to draw the child into the Biblical and Liturgical themes. These materials are always available to the children during their work time so they have additional opportunity to absorb the lessons. The following is a summary to the presentations offered for Level I. Classes are structured to offer a time of prayer and song, a time for the “presentation” and a time for individual work by the child. -

The Light of the World

I AM THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD DATE WEEK OVERVIEW KEY VERSE August 22 & 23 2 of 7 John 8:12-30 John 8:12 To appreciate the words of Jesus in chapter 8, we must understand the context. In chapter 7 the Jewish people were celebrating one of their week-long feasts, the Feast of Tabernacles. One of the most jubilant feasts, it is filled with both celebration and remembrance, honoring God’s provision and protection for the people of Israel during their 40 years wandering in the wilderness. For seven days of the feast, people live in temporary tent structures as they did in the wilderness during the time of Moses. The Lord Himself was present with the Israelites in the desert, in a tented temple called the Tabernacle. The feast also celebrates His presence as He tabernacles (dwells) with us. 1 The Feast of Tabernacles takes place during the early fall in the harvest season. Harvest was another cause for celebration; honoring the Lord’s provisions through their crops. Though this was a celebratory time for the people, it was a challenging time for Jesus. It was during this festival that the opposition began to grow and intensify towards Him and His ministry. However, this did not distract Jesus from His message. He used several observed rituals as teachable moments to talk about “living water” in chapter 7 and “light” in chapter 8. Continued on page 15 > SETTING THE STAGE LESSON OUTLINE THINGS TO KNOW 1. I Am • The Feast of Tabernacles was also known as the 2. -

The Meaning and Message of the Beatitudes in the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7) Ranko Stefanovic Andrews University

The Meaning and Message of the Beatitudes in the Sermon On the Mount (Matthew 5-7) Ranko Stefanovic Andrews University The Sermon on the Mount recorded in Matthew 5-7 is probably one of the best known of Jesus’ teachings recorded in the Gospels. This is the first of the five discourses in Matthew that Jesus delivered on an unnamed mount that has traditionally been located on the northwest shore of the Sea of Galilee near Capernaum, which is today marked by the Church of the Beatitudes. New Testament scholarship has treated the Sermon on the Mount as a collection of short sayings spoken by the historical Jesus on different occasions, which Matthew, in this view, redactionally put into one sermon.1 A similar version of the Sermon is found in Luke 6:20-49, known as the Sermon on the Plain, which has been commonly regarded as a Lucan variant of the same discourse. 2 The position taken in this paper is, first of all, that the Matthean and Lucan versions are two different sermons with similar content delivered by Jesus on two different occasions. 3 Secondly, it seems almost certain that the two discourses are summaries of much longer ones, each with a different emphasis, spiritual and physical respectively. Whatever position one takes, it appears that the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew is not just a collection of randomly selected pieces; the discourse displays one coherent literary theme. The Sermon is introduced with the Beatitudes, which are concluded with a couplet of short metaphoric parables on salt and light. -

The Light of the World

The Light of the World Theme Jesus is the one true light. We are his witnesses. Object A strand of Christmas lights; construction paper; scissors; pens - one per child; tape Scripture John 1:6-8, 19-28 Video Connection: Tell Me the Story: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_OO84K9RuF0 Children’s Christmas Songs- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cSLrFVR-Hqw&list=PLg8UufkzWLCASnhbmrb3XOPXFdp8_yB3c “Light of the World”- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eI302Av7vSI Lesson Cut circles from the construction paper to symbolize light bulbs. Make them large enough so kids can write a word or two on them. Turn down the classroom lights, and plug in the Christmas lights so they light the room. Our Bible reading for today tells us that God sent a man, John the Baptist, to tell about the light--Jesus--so that everyone would believe. John wasn't the light. He only came to tell others about the light. Jesus is the one true light, who gives light to everyone. Let’s think about lights in our lives to help us think about that. When do you need light or what do you need light for? Encourage kids to try to work together to name a use for light for every bulb on the Christmas strand. At this time of year, we see lights everywhere that remind us of the coming of Jesus, the true light that John told about. Turn and tell a neighbor in one sentence about the coolest Christmas lights you’ve seen. Allow time. Those lights can help us remember that Jesus is the one true light in our hearts and in our lives. -

A Good Shepherd Story of Jesus Light of the World

A Good Shepherd Story of Jesus Light of the World Adapted by: Brenda 1. Stobbe Illustrations by: Jennifer Schoenberg & Tiffany DeGraaf Activity Sheets, Laminated Cards and Art Editing by: Tiffany DeGraaf Good Shepherd, Inc®. 2000 Good Shepherd, a Registered Trademark of Good Shepherd, Inc. All Rights Reserved Printed in the U.S.A. LIGHT OF THE WORLD ..... MATERIALS NEEDED -medium wicker basket to hold -wooden Jesus figure -2 wooden onlooker figures -wooden Pharisee figure -laminated Light card 1 Jesus Pharisee Two Onlookers 2 LIGHT OF THE WORLD ... JOHN 8:12-20 ACTIONS WORDS After speaking, stand and get the story Watch carefully where I go to get this basket from the shelf and return to the story so you will know where to find it if circle. you choose to make it your work today or another day. Allow 10-15 seconds of silence as you All of the words to this story are inside reverently touch one or more of the of me. If you will make silence with me wooden figures to center yourself and I will find all the words to this story of the children. God's people. Place the Jesus figure toward at the Jesus spent much of his time on earth center of the storytelling area. helping people understand who he was. Rest your hand lightly on the Jesus When they wondered if Jesus was really figure. the Savior, the Messiah he told them about himself in different ways. Place the two onlooker figures and the Jesus spoke to the people who followed Pharisee figure next to Jesus. -

Keeping a Holy Lent

Keeping a Holy Lent Lenten Programs & Worship Services 2016 Wycliffe Presbyterian Church 1445 N. Great Neck Road Virginia Beach, Virginia 23454 www.wycliffepresbyterian.org Phone: 757-496-2620 What is Lent? Lent is a season of preparation leading up to Easter. It is the forty days plus the six Sundays before Easter. For centuries, it has been observed as a special time of self examination and penitence. Lent is a time for concentration on fundamental values and priorities. Presbyterians use this time to focus specifically on their baptism into the faith and what it means to them. This is a great time to focus on reading the Bible or to begin the day with Lenten devotions. There are copies of the Upper Room in the narthex and reception area. Christian Education During Lent, the Adult Sunday School class will be using Adam Hamilton’s DVD series The Way: Walking in the Footsteps of Jesus. We will explore and discuss Jesus’ teaching ministry from his baptism through Holy Week in Jerusalem. Classes for the six weeks of Lent start on Sunday, February 14 at 9 AM in room 210. No homework required; come join us for Lent. In February, our preschool through elementary students will be studying the Ten Men Healed, The Good Samaritan, Prodigal Son, and Mary and Martha. In March they will learn about Zacchaeus, Last Supper, Holy Week, and The Empty Tomb. Their classes meet each week at 10:00 following the Pastor's message with the children. Worship Ash Wednesday February 10 at 7 pm Wycliffe will host a joint Ash Wednesday service with Virginia Beach Christian Church at 7:00 pm on February 10. -

St Mary Magdalene

Petra News St Mary Magdalene Week of July 19th 2020 Sunday, July 19th 2020 Holy Fathers of the 4th Ecumenical Council Sts Peter & Paul Weekly Services Resurrection Hymn (Plagal 1st Tone) Wednesday Morning, July 22 “Eteranl with the Father and the Spirit is the Word, Feast St Mary Magdalene Who of a Virgin was begotten for our salvation. Orthros __________________ 8am As the faithful we both praise and worship Him, Divine Liturgy _____________ 9am for in the flesh did He consent to ascend unto the Cross, Wednesday Evening, July 22 and death did He endure and He raised unto life Paraclesis to St. Niciforos Leper the dead through His all glorious resurrection.” & Wonderwonder __________ 6pm Hymn for the Holy Fathers Saturday Morning, July 25 “Supremely blessed are You, O Christ our God. Dormition St Anna You established the holy Fathers upon the earth as beacons, Orthros __________________ 8am and through them You have guided us all to the true Faith, Divine Liturgy _____________ 9am O greatly merciful One, glory be to You.” Saturday Evening, July 25 Hymn for Sts Peter and Paul Great Vespers ______________ 5pm “O leaders of the Apostles, and teachers of the world, intercede with the Master of all Sign-up For Services that He may grant peace unto the Lord, and to our souls His great mercy.” Reserve a spot by visiting the church website at Kontakion Hymn stspeterandpaulboulder.org “A protection of Christians unshamable, Please email Shanyn Bateh at intercessor to our holy Maker unwavering, [email protected] if you have any questions. Thank you. -

When Jesus Comes, You Find Your Purpose John 1:6-9, 15

1 WHEN JESUS COMES, YOU FIND YOUR PURPOSE JOHN 1:6-9, 15 Every kid who’s sat in a science class has heard of Isaac Newton’s famous encounter with a falling apple. Newton was the first to explain the laws of gravity back in the 1600s which revolutionized the study of astronomy and so much more. But few people know that if it weren’t for another scientist named Edmund Halley, the world might never have heard of Isaac Newton. It was Halley who challenged Newton to think through his original ideas. It was Halley who corrected Newton’s mathematical errors and prepared geometrical figures to support Newton’s discoveries. It was Halley who persuaded Newton to write his great book, Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. It was Halley who edited and supervised the publication of that book, and even financed its printing although Newton was wealthier than Halley and could have easily paid to have it printed himself. Historians consider it one of the most selfless examples in the history of science. Newton began almost immediately to reap the rewards of his new prominence. Halley received little credit. Now, he did use Newton’s principles to predict the orbit and return of the comet that now bears his name. You’ve heard of Halley’s Comet that comes close to Earth every 76 years. But otherwise you don’t hear a lot about Edmund Halley. He’s a great example of a devoted scientist who didn’t care who received the credit as long as the cause of science advanced. -

TC SS 5.6 YR1 SPRG CM 32806 Layout 1

COPY MASTERS GRADES 5-6 YEAR 1 | SPRING Sunday School I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life. John 8:12 (NIV 1984) Project Coordinators: Owen Dorn, Raymond Schumacher Editorial Team: Debera Fellers, Lynn Groth, Emily Kratz, Jane Mose, Raymond Schumacher, Jennifer Werre Art Director: Karen Knutson Design Team: Pamela Dunn, Sarah Oberhofer, Lynda Williams Illustrators (line art): Dan Grossmann, Nan Pollard Illustrator (full-color): Frank Ordaz We extend our thanks to the many employees of Northwestern Publishing House who have contributed to this project. Hymn and hymnal references, unless otherwise indicated, are to Christian Worship: A Lutheran Hymnal. © 1993 by Northwestern Publishing House. Catechism materials are taken from Luther’s Catechism: Revised. © 1998 by Northwestern Publishing House. Christ-Light and the Christ-Light logo are registered property of Northwestern Publishing House. Northwestern Publishing House 1250 N. 113th St., Milwaukee, WI 53226-3284 www.nph.net © 2012 by Northwestern Publishing House Published 2012 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8100-2136-5 All rights reserved. The contents of this CD may be reproduced and used only by the purchasing school or congregation. Sharing this material with other congregations or schools is prohibited. Name ___________________________ CROSS-words Across Down 2. INRI stands for Jesus of Nazareth (the Nazarene), the ___ of the Jews. 1. Roman ___ guarded the crucifixion site. 7. Jesus refused to drink the wine and gall, which 3. ___ are the four letters often shown was a ___. above Jesus’ cross.