Grand Central Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS by Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee

Field Notes - Spring 2016 Issue RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS By Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee We have been reviewing new books about the Olmsteds and the art of landscape architecture for so long that the book section of our website is beginning to resemble a bibliography. To make this resource more useful for researchers and interested readers, we’re beginning a series of articles about older publications that remain useful and enjoyable. We hope to focus on the landmarks of the Olmsted literature that appeared before the creation of our website as well as shorter writings that were not intended to be scholarly works or best sellers but that add to our understanding of Olmsted projects and themes. THE OLMSTEDS AND THE VANDERBILTS The Vanderbilts and the Gilded Age: Architectural Aspirations 1879-1901. by John Foreman and Robbe Pierce Stimson, Introduction by Louis Auchincloss. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991, 341 pages. At his death, William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) was the richest man in America. In the last eight years of his life, he had more than doubled the fortune he had inherited from his father, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877), who had created an empire from shipping and then done the same thing with the New York Central Railroad. William Henry left the bulk of his estate to his two eldest sons, but each of his two other sons and four daughters received five million dollars in cash and another five million in trust. This money supported a Vanderbilt building boom that remains unrivaled, including palaces along Fifth Avenue in New York, aristocratic complexes in the surrounding countryside, and palatial “cottages” at the fashionable country resorts. -

Old Buildings, New Views Recent Renovations Around Town Have Uncovered Views of Manhattan That Had Been Hiding in Plain Sight

The New York Times: Real Estate May 7, 2021 Old Buildings, New Views Recent renovations around town have uncovered views of Manhattan that had been hiding in plain sight. By Caroline Biggs Impressions: 43,264,806 While New York City’s skyline is ever changing, some recent construction and additions to historic buildings across the city have revealed some formerly hidden, but spectacular, views to the world. These views range from close-up looks at architectural details that previously might have been visible only to a select few, to bird’s-eye views of towers and cupolas that until The New York Times: Real Estate May 7, 2021 recently could only be viewed from the street. They provide a novel way to see parts of Manhattan and shine a spotlight on design elements that have largely been hiding in plain sight. The structures include office buildings that have created new residential spaces, like the Woolworth Building in Lower Manhattan; historic buildings that have had towers added or converted to create luxury housing, like Steinway Hall on West 57th Street and the Waldorf Astoria New York; and brand-new condo towers that allow interesting new vantages of nearby landmarks. “Through the first decades of the 20th century, architects generally had the belief that the entire building should be designed, from sidewalk to summit,” said Carol Willis, an architectural historian and founder and director of the Skyscraper Museum. “Elaborate ornament was an integral part of both architectural design and the practice of building industry.” In the examples that we share with you below, some of this lofty ornamentation is now available for view thanks to new residential developments that have recently come to market. -

Page Numbers in Italics Refer to Illustrations. Abenad

INDEX Page numbers in italics refer to illustrations. Abenad Corporation, 42 Ballard, William F. R., 247, 252, 270 Abrams, Charles, 191 Barnes, Edward Larabee, 139, 144 Acker, Ed, 359 Barnett, Jonathan, 277 Action Group for Better Architecture in New Bauen + Wohnen, 266 York (AGBANY), 326–327 Beaux-Arts architecture, xiv, 35, 76, 255, 256, Airline industry, xiv, 22, 26, 32, 128, 311, 314, 289, 331, 333, 339, 344, 371. See also 346, 357–360, 361–362, 386 Grand Central Terminal Albers, Josef, 142–143, 153, 228, 296, 354, Belle, John (Beyer Blinder Belle Architects), 407n156 354 American Institute of Architects (AIA), 3, 35, Belluschi, Pietro, 70–77, 71, 80, 223, 237, 328 75, 262, 282, 337 AIA Gold Medal, 277, 281 Conference on Ugliness, 178–179 and the Architectural Record, 188, 190, 233, New York Chapter, 2, 157 235, 277 American Institute of Planners, 157 and art work, Pan Am Building, 141–144 Andrews, Wayne, 175–176, 248, 370 as co-designer of the Pan Am Building, xiii, 2, “Anti-Uglies,” 177, 327 50, 59, 77, 84, 87, 117, 156–157, 159, 160– “Apollo in the democracy” (concept), 67–69, 163, 165, 173, 212, 248, 269, 275, 304, 353, 159. See also Gropius, Walter 376 (see also Gropius/Belluschi/Roth collab- Apollo in the Democracy (book), 294–295. See oration) also Gropius, Walter on collaboration of art and architecture, 142– Collins review of, 294–295 143 Architectural criticism, xiv, xvi, 53, 56, 58, 227, collaboration with Gropius, 72, 75, 104, 282, 232, 257, 384–385, 396n85. See also 397n119 Huxtable, Ada Louise contract with Wolfson, 60–61, -

Handout 3 Morgan and Vanderbilt - Documents

Handout 3 Morgan and Vanderbilt - Documents J.P. Morgan One of the most powerful bankers of his era, J. P. (John Pierpont) Morgan (1837-1913) financed railroads and helped organize U. S. Steel, General Electric, and other major corporations. The Connecticut native followed his wealthy father into the banking business in the late 1850s, and in 1871 formed a partnership with Philadelphia banker Anthony Drexel. In 1895, their firm was reorganized as J.P. Morgan & Company, a predecessor of the modern-day financial giant JPMorgan Chase [& Co.]. Morgan used his influence to help stabilize American financial markets during several economic crises, including the panic of 1907. However, he faced criticism that he had too much power and was accused of manipulating the nation’s financial system for his own gain. The Gilded Age titan spent a significant portion of his wealth amassing a vast art collection. J.P. Morgan: Early Years and Family John Pierpont Morgan was born into a distinguished New England family on April 17, 1837, in Hartford, Connecticut. One of his maternal relatives, James Pierpont (1659-1714), was a founder of Yale University; his paternal grandfather was a founder of the Aetna Insurance Company; and his father, Junius Spencer Morgan (1813-90), ran a successful Hartford dry-goods company before becoming a partner in a London-based merchant banking firm. After graduating from high school in Boston in 1854, Pierpont, as he was known, studied in Europe, where he learned French and German, then returned to New York in 1857 to begin his finance career In 1861, Morgan married Amelia Sturges, the daughter of a wealthy New York businessman. -

2021 NYYC Foundation Newsletter Issue #2

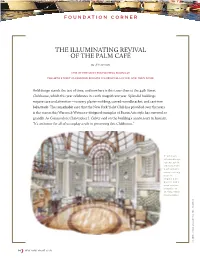

FOUNDATION CORNER THE ILLUMINATING REVIVAL OF THE PALM CAFÉ by Jill Connors ONE OF THE MOST ENCHANTING ROOMS AT THE 44TH STREET CLUBHOUSE REGAINS ITS ORIGINAL LUSTER, AND THEN SOME. Bold design stands the test of time, and nowhere is this truer than at the 44th Street Clubhouse, which this year celebrates its 120th magnificent year. Splendid buildings require care and attention—to every plaster molding, carved-wood bracket, and cast-iron balustrade. The remarkable care that the New York Yacht Club has provided over the years is the reason this Warren & Wetmore-designed exemplar of Beaux Arts style has survived so grandly. As Commodore Christopher J. Culver said on the building’s anniversary in January, “It’s an honor for all of us to play a role in preserving this Clubhouse.” C2 Limited’s interior-design scheme for the renewed Palm Café includes casual seating near the original ban- quettes and a color scheme evocative of an early 1900s conservatory. LIMITED DESIGN ASSOCIATES & BRYN BACHMAN & BRYN LIMITED DESIGN ASSOCIATES 2 C 14 NEW YORK YACHT CLUB FOUNDATION CORNER The New York Yacht Club was wearing thin and the Foundation is particularly lighting gave no hint of the important in this regard, original natural light that as it was created in 2007 would have made the room for the sole purpose of so pleasurable. A further maintaining both of the issue was the lack of heating club’s historic properties: the or cooling in the space. All 44th Street Clubhouse and these issues fell neatly under Newport’s Harbour Court. -

The Men Who Built America

“THE AMERICAN ECONOMY WAS LINKED BY RAILROADS, FUELED BY OIL AND BUILT BY STEEL.” Cornelius Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Episode 1: A New WAR BEGINS J.P. Morgan, Henry Ford – their names are synonymous with As the nation attempts to rebuild following the destruction of the innovation, big business and the American Dream. These leaders Civil War, Cornelius Vanderbilt is the first to see the need for unity sparked incredible advances in technology while struggling to to regain America’s stature in the world. Vanderbilt makes his mark consolidate their industries and rise to the top in shipping and then the railroad industry. Railroads stitch together of the business world. The Men Who Built America™ chronicles the the nation, stimulating the economy by making it easier to move connections between these iconic businessmen and explores the goods across the country. But Vanderbilt faces intense competition way they shaped the country, transforming the early on, showing that captains of industry will always be chal- U.S. into a global superpower in just 50 years. lenged by new innovators and mavericks. Tracing their roles in the oil, steel, railroad, auto and financial Key TERMS to DEFINE industries, this series uses stunning CGI and little-known stories to ARCHETYPE, ENTREPRENEUR, INFRASTRUCTURE, INGENUITY, examine the lives of these iconic tycoons. How did these leaders INNOVATION advance progress, and what were the costs and consequences of American industrial growth? What role did everyday Americans Discussion Questions play in this growth, and how were their voices heard? This series is an excellent companion for course units on business, American 1. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUGUST 1975 VOL. XIX NO. 4 PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. 19103 • Spiro K. Kostof, President • Editor: Thomas M. Slade, 3901 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20008 • Assistant Editor: Elisabeth W. Potter, 22927 Edmonds Way, Edmonds, Washington, 98020 SAH NOTICES the Subcommittee on Science, Research, and Technology of the U.S. House Committee on Science and Technology ... 1976 Annual Meeting, Philadelphia (May 19-24). Marian C. HYMAN MYERS AND GEORGE THOMAS organized an ex Donnelly, general chairman; Charles E. Peterson, FAIA, honor hibition of photographs, original drawings, hardware, and ary local chairman; and R. Damon Childs, local chairman. The plans of restoration work now in progress at the Pennsylvania call for papers appeared in the April Newsletter. Academy of Fine Arts designed by Furness and Hewitt. Shown at the AlA Gallery in Philadelphia last month, the exhibition 1977 Annual Meeting, Los Angeles (with College Art Associa material was drawn from private collections as well as those of tion) - February 2-7. Adolf K. Placzek, Columbia University, the Academy and the Philadelphia Museum of Art ... EVA D. is general chairman of the meeting. David S. Gebhard, Univer NOLL addressed the annual meeting of the Chester County sity of California, Santa Barbara, will act as local chairman. Historical Society last May on the subject of "Communica The call for papers appeared in the June Newsletter. tions Between the Colonies." Mrs. Noll, who is historian for Project 1776 sponsored by the Bicentennial Commission of 1975 Annual Tour- Annapolis and Southern Maryland (Octo Pennsylvania, spoke the preceding month in Pittsburgh at the ber 1-5). -

Landmarks Preservation Commission April 18, 2006, Designation List 372 LP-2185

Landmarks Preservation Commission April 18, 2006, Designation List 372 LP-2185 STEWART & COMPANY BUILDING, 402-404 Fifth Avenue (aka 2 West 37th Street), Manhattan. Built 1914; [Whitney] Warren & [Charles D.] Wetmore, architects; George A. Fuller Co., builders; New York Architectural Terra Cotta Company, terra cotta manufacturer. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 838, Lot. 48 On October 18, 2005, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of Stewart & Company building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provision of law. Three people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the property’s owners. In addition, the Commission received two letters in support of designation. Summary The Stewart & Company Building, designed by Warren and Wetmore, is one of the firm’s most unusual designs. The 1914 building reflects the unusual combination of diverse influences such as the 18th century British neo-Classical movement and the late 19th century Chicago School of Architecture style. The blue and white ornament of the terra cotta cladding is reminiscent of the 18th century neo-Classical movement in England, and specifically two of the most important proponents of the movement, Josiah Wedgwood and Robert Adam. Characteristic of the Chicago style are steel frame construction, masonry cladding that was usually terra cotta, large areas of glazing, usually featuring tripartite windows known as Chicago windows, and a tripartite vertical design. As the commercial center of Manhattan moved uptown so did the location of department stores. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMEN ,. JF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Grand Central Terminal AND/OR COMMON Grand Central Terminal LOCATION STREETS,NUMBER 71-105 East 42nd Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT New York _ VICINITY OF 18th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE New York New York 36 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT —PUBLIC X2DCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM 2^BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE _ UNOCCUPIED X.COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _S!TE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _ OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X_YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL ^-TRANSPORTATION _NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Pennsylvania Central Transportation Company STREET & NUMBER 466 Lexington Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE New York VICINITY OF New York LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, New York County Hall of Records REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. STREET& NUMBER 31 Chambers Street CITY, TOWN STATE New York New York REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE New York City Landmarks Commission DATE 1967 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY x_LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE New York New Yn-rlf DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^-ORIGINAL SITE X_GOOD —RUINS X_ALTERED _MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE A complete contemporary description would be lengthy—in the brief: "The terminal has two levels. The upper one of these, 20 ft. -

D'annunzio at Fiume, Quaderni, Vol

Pamela Ballinger JOHN HOPKINS UNIVERSITY REWRITING THE TEXT OF THE NATION: D'ANNUNZIO A T FIUME P. BALL!NGER, D'Annunzio at Fiume, Quaderni, vol. Xl, 1997, p. 117- 155 119 Introduction: In the house of the nation Perched in the hills above the resort town ofGardone Riviera on the northern Jtalian Lago di Garda stands the ornate and idiosyncratic villa known as the Vittoria/e. Visitors invariably express astonishment upon first viewing the villa, which almost overflowswith statues, objets d'art, Persian carpets, religious icons, and war relics. Countless mottos and inscriptions decorate its walls and niches; garish reds and blues dazzle the eyes in this otherwise dusky building into which little sunlight penetrates. The villa stands as a self-created monument to the · lifework of its former owner, the poet and war hero Gabriele D'Annunzio, and to his vision of a revitalized Italian nation. Crossing the Vittoria/e 's threshold, the visitor enters the symbolic universe of this poet who, having fa i led to realize as political reality his vision of a new Italian identity fo unded upon a proto-fascist military ethos, subsequently dedicated himself to memorializing his efforts by transforming his residence into a literal museum and tempie. Pausing at the gateway portico fo rmed by two triumphal arches, the visitor's gaze first meets a fo untain whose inscription reveals D' Annunzio's aim: "Dentro da questa cerchia triplice di mura, ove tradotto e già in pietre vive quel libro religioso ch'io mi pensai preposto ai riti della Patria e dai vincitori latini chiamato Vittoria/e "(Mazza 1987: 22). -

M Grand Central Post Office Annex Southwest Corner 45Th Street and -. Lexington Avenue New York City New York HABS No. NY-6302 I

Grand Central Post Office Annex HABS No. NY-6302 m Southwest corner 45th Street and -. Lexington Avenue New York City New York C ip ; PHOTOGRAPHS • WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY MID-ATLANTIC REGION, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PHILADELPHIA, PENNSYLVANIA 19106 *" HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY GRAND CENTRAL POST OFFICE ANNEX HABS No. NY-6302 Location: The block bounded by 45th Street, Lexington Avenue, Depew Place, and the Graybar Building (the southwest corner of 45th Street and Lexington Avenue), New York City, New York. USGS Central Park Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates: 18 .586450 .441166 Present Owner: United States Government Present Occupant: United States Post Office Significance The Grand Central Post Office Annex was envisioned as a key element of the Grand Central Station complex, one of the most important examples of monumental urban planning in the United States. Designed by the nationally significant architectural firm of Warren and Wetmore, in collaboration with the firm of Reed and Stem, the complex was built between 1903 and 1914 for a railroad cartel headed by the mighty New York Central Railroad. It included the massive Terminal itself, surrounded by raised traffic viaduct, the Post Office Annex, railroad offices on 45th Street, and a vast underground network of tracks and platforms. The breadth of the project and the richness of its execution documents not only the tremen- dous wealth of the railroads during the period, but also their influence in shaping the image of American cities. The Annex was constructed as part of the complex to provide railroad-related office space on the upper floors while the lower stories were leased as a postal facility. -

The Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune

Ml' P WHi|i^\v^\\ k Jll^^K., VI p MsW-'^ K__, J*-::T-'7^ j LIBRARY )rigliam i oiMig U mversat FROM. Call Ace. 2764 No &2i?.-^ No ill -^aa^ceee*- Britfham Voung il/ Academy, i "^ Acc. No. ^7^V ' Section -^^ i^y I '^ ^f/ Shelf . j> \J>\ No. ^^>^ Digitized by tine Internet Arcinive in 2010 witii funding from Brigiiam Young University littp://www.arcliive.org/details/vanderbiltsstoryOOcrof -^^ V !<%> COMMODORE VANDERBILT. ? hr^ t-^ ^- -v^' f ^N\ ^ 9^S, 3 '^'^'JhE VANDERBILTS THE STORY OF THEIR FORTUNE BT W. A. CKOFFUT A0THOR OF "a helping HAND," "A MIDSUMMER LARK," "THE BOUKBON BALLADS," " HISTOBr OF CONNECTICUT," ETC. CHICAGO AND NEW YORK BELFOBD, CLARKE & COMPANY Publishers 1/ COPYKIGHT, 1886, BY BELFORD, CLAEKE & COMPANY. TROWS PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY, NEW YORK. PREFACE This is a history of the Yanderbilt family, with a record of their vicissitudes, and a chronicle of the method by which their wealth has been acquired. It is confidently put forth as a work which should fall into the hands of boys and young men—of all who aspire to become Cap- tains of Industry or leaders of their fellows in the sharp and wholesome competitions of life. In preparing these pages, the author has had an am- bition, not merely to give a biographical picture of sire, son, and grandsons and descendants, but to consider their relation to society, to measure the significance and the influence of their fortune, to ascertain where their money came from, to inquire whether others are poorer because they are rich, whether they are hindering or promoting civilization, whether they and such as they are impediments to the welfare of the human i-ace.