Erik Van Den Berg BW.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE TRANSFORMATION of ELEANOR ROOSEVELT Nell."

JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY AND HISTORY OF EDUCATION THE TRANSFORMATION OF ELEANOR ROOSEVELT Donna Lee Younker University of Central Oklahoma, Emeritus Ifwe women ever feel that something serious is threatening our homes and our children's lives, then we may awaken to the political and economic power that is ours. Not to work to elect a woman, but to work for a cause. Eleanor Roosevelt, 1935 Saturday Evening Post (August 11, 1935).* Foreword tears and loss.2 Joseph P. Lash, who over a friendship Anna Eleanor Roosevelt was born before women lasting twenty-two years had almost a filial devotion to were allowed to vote. For Eleanor Roosevelt feminism her, writes that her intense and crucial girlhood was and world peace were inexorably intertwined. This lived not only in the Victorian age, but another world.3 paper is a psychobiography, tracing her transformation Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., describes the social milieu from a private to a public person. It carefully chronicles in which she grew up as "the old New York of Edith her development from a giggling debutante to a Wharton where rigid etiquette concealed private hells powerful political leader. The focus of this paper has and neuroses lurked under the crinoline.4 been placed on her first emergence in the years after Anna Eleanor Roosevelt was born on October 11, World War I as a leader for the Nineteenth Amendment 1884. Her mother, Anna Hall Roosevelt, died when she to the Constitution and of the movement for the League was eight years old. Her father, Elliott Roosevelt, the of Nations. -

Mason Williams

City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Mason Williams All Rights Reserved Abstract City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams This dissertation offers a new account of New York City’s politics and government in the 1930s and 1940s. Focusing on the development of the functions and capacities of the municipal state, it examines three sets of interrelated political changes: the triumph of “municipal reform” over the institutions and practices of the Tammany Hall political machine and its outer-borough counterparts; the incorporation of hundreds of thousands of new voters into the electorate and into urban political life more broadly; and the development of an ambitious and capacious public sector—what Joshua Freeman has recently described as a “social democratic polity.” It places these developments within the context of the national New Deal, showing how national officials, responding to the limitations of the American central state, utilized the planning and operational capacities of local governments to meet their own imperatives; and how national initiatives fed back into subnational politics, redrawing the bounds of what was possible in local government as well as altering the strength and orientation of local political organizations. The dissertation thus seeks not only to provide a more robust account of this crucial passage in the political history of America’s largest city, but also to shed new light on the history of the national New Deal—in particular, its relation to the urban social reform movements of the Progressive Era, the long-term effects of short-lived programs such as work relief and price control, and the roles of federalism and localism in New Deal statecraft. -

Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE. NEW YORK "This is the house in which my husband was born and brought up.... He alwl!Ys felt that this was his home, and he loved the house and the view, the woods, special trees .... " -Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt Franklin D. Roosevelt. 32d President of the United States was born in this home on January 30. 1882. He was the only child of James and Sara Roosevelt. Franklin Roosevelt spent much of his life here. Here Franklin-the toddler. the little boy. the young man-was shaped and grew to maturity. Here he brought his bride. Eleanor. in 1905. and here they raised their five children. From here he began his political career that stretched from the New York State Senate to the White House. Roose- velt was a State senator. 1911-13. Assistant Sec- retary of the Navy under Woodrow Wilson. 1913- 20. and unsuccessful vice-presidential candidate in 1920. Then. in 1921. he contracted infantile paralysis. During his struggle to conquer the disease he spent much time here. He refused to become an invalid and reentered politics. He was elected Governor of New York in 1928 and 1930 and President of the United States in 1932. As Governor and President. he came here as often as he could for respite from the turmoil of public life. On April 15. 1945. 3 days after his death in Warm Springs. Ga.. President Roosevelt was buried in the family rose garden. Seventeen years later. on November 10. 1962. Mrs. Roosevelt was buried beside the President. -

Ftssrjf *•* ^ All Sales Final

Notes From the Social Calendar of Washington and Its Environs Mrs. Roosevelt Attends Morning Musicale By the Way— Beth Blaine= With Guests ^RRIVING in Washington this afternoon in time to attend the tea at the Polish Embassy are Mrs. Harold E. Talbott of New York and Long Island and Miss Beatrice Patterson of Wife of the President to Give Philadelphia. The tea today at the Embassy is given more or less in compliment Party for Grandchildren to the former Jane Sanford and her husoand, Mario Panza; who are here en route to Palm Beach. They are stopping with Prince This Afternoon. del Drago of the Italian Embassy, who was best man at their last ROOSEVELT attended Mrs. Lawrence Townsend’s wedding year. Tonight Mrs. Talbott and Miss Patterson will be seen at the morning musicale today, having as guests Mme. Saito, National Theater and later at Mr. and Mrs. Mathews Dicks’ supper, wife of the MRS. Japanese Ambassador; Countess van der which promises to be one of the better late evening parties. They Straten-Ponthoz, wife of the Ambassador of Belgium, and her are checking in at the Mayflower around 4 o’clock and will stay daughters-in-law, Mrs. James Roosevelt and Mrs. Franklin over until after lunch tomorrow. * * * * Roosevelt, jr. The program was given by Bino Rabinof, violinist, and Beveridge Webster, pianist. This# afternoon Mrs. Roosevelt 'J'O LOOK at Mrs. Albert Cushing Read it seems impossible that will give a party for her grandchildren, Chandler Roosevelt and she could be celebrating her twentieth wedding anniversary, very youthful Elliott Roosevelt, jr. -

The American Liberty League and the Rise of Constitutional Nationalism Jared Goldstein Roger Williams University School of Law

Roger Williams University DOCS@RWU Law Faculty Scholarship Law Faculty Scholarship Winter 2014 The American Liberty League and the Rise of Constitutional Nationalism Jared Goldstein Roger Williams University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.rwu.edu/law_fac_fs Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Politics Commons Recommended Citation Jared A. Goldstein, The American Liberty League and the Rise of Constitutional Nationalism, 86 Temp. L. Rev. 287, 330 (2014) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Scholarship at DOCS@RWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DOCS@RWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: Jared A. Goldstein, The American Liberty League and the Rise of Constitutional Nationalism, 86 Temp. L. Rev. 287, 330 (2014) Provided by: Roger Williams University School of Law Library Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Thu Nov 16 15:40:33 2017 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device THE AMERICAN LIBERTY LEAGUE AND THE RISE OF CONSTITUTIONAL NATIONALISM JaredA. Goldstein* This Article launches a project to identify constitutional nationalism-the conviction that the nation'sfundamentalvalues are embodied in the Constitution-as a recurring phenomenon in American public life that has profoundly affected both popular and elite understandingof the Constitution. -

Freedom from Fear? the Oxford American

Staddon, J. (1996) Freedom from fear? The Oxford American. Spring, pp. 103-106. Freedom from Fear? How belief in a pain-free utopia has discredited punishment and de-civilized society. by John Staddon Successful political slogans are usually phony. They succeed because they promise gain without pain, the reconcil- ing of the irreconcilable and win-win in a zero-sum world. Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “four freedoms” are still remembered after two generations. Freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear all sound very fine, but this slogan bears scrutiny no better than others. Freedom of speech and religion are reasonable enough, perhaps. But freedom from want is problematic: Who shall define ‘want’? When does ‘want’ or ‘need’ turn into ‘wish’ and ‘desire’? And whose freedom to spend his own money shall be abridged to satisfy the presumed needs of others? But most pernicious of all is “freedom from fear,” because it seems self-evident. Punishment and the Creed of Mental Health Yet the idea that mankind could ever be free of fear is as odd as it is recent. The ancients knew the world as full of evil spirits. Sin and retribution are at the root of Judaeo-Christianity. Modern biology sees evolution as fre- quently, if not invariably, “red in tooth and claw.” But ever since Freud, a new creed, the creed of psychotherapy, has offered the prospect of mental perfection, of life not just free of evil but innocent even of the concept. The vari- eties of professional psychology and psychiatry from psychoanalysis to behaviorism, while they have argued about everything else, agree that fear can and should be banished. -

Plain, Ordinary Mrs. Roosevelt

First 1 Reading Instructions 1. As you read, mark a ? wherever you are confused or curious about something. 2. After reading, look at the places you marked. Write your questions in the margins. 3. Circle two questions to bring to the sharing questions activity: • A question about a part that confuses you the most. • A question about a part that interests you the most. Plain, Ordinary Mrs. Roosevelt Jodi Libretti The highlighted words n 1932 Americans elected Franklin Delano Roosevelt, will be important to know I as you work on this unit. also known as FDR, as their president. People were looking for someone who could lead the country out of the Great QUESTIONS Depression. Since 1929 the United States had been in terrible trouble. Banks went out of business, and millions of people lost all of their savings. One out of every five people lost their jobs. To make matters worse, terrible droughts were drying up America’s farmland. Land across the Great Plains turned to dust and was literally blowing away. People were scared and desperate. In his first speech as president, FDR brought hope to people when he said, “the only thing we have to fear is fear Great Depression: the period between 1929–1939 when the United States and many other countries faced major financial problems literally: actually 104 Nonfiction Inquiry 5 itself.” He also brought them his wife Eleanor. Americans didn’t know it yet, but she would be a First Lady like no other. Eleanor the Activist Eleanor Roosevelt stood nearly six feet tall and had buck teeth and a high voice. -

Martin Van Buren National Historic Site

M ARTIN VAN BUREN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY, 1974-2006 SUZANNE JULIN NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NORTHEAST REGION HISTORY PROGRAM JULY 2011 i Cover Illustration: Exterior Restoration of Lindenwald, c. 1980. Source: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgements ix Introduction 1 Chapter One: Recognizing Lindenwald: The Establishment Of Martin Van Buren National Historic Site 5 Chapter Two: Toward 1982: The Race To The Van Buren Bicentennial 27 Chapter Three: Saving Lindenwald: Restoration, Preservation, Collections, and Planning, 1982-1987 55 Chapter Four: Finding Space: Facilities And Boundaries, 1982-1991 73 Chapter Five: Interpreting Martin Van Buren And Lindenwald, 1980-2000 93 Chapter Six: Finding Compromises: New Facilities And The Protection of Lindenwald, 1992-2006 111 Chapter Seven: New Possibilities: Planning, Interpretation and Boundary Expansion 2000-2006 127 Conclusion: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Administrative History 143 Appendixes: Appendix A: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Visitation, 1977-2005 145 Appendix B: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Staffi ng 147 Appendix C: Martin Van Buren National Historic Site Studies, Reports, And Planning Documents 1936-2006 151 Bibliography 153 Index 159 v LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1.1. Location of MAVA on Route 9H in Kinderhook, NY Figure 1.2. Portrait of the young Martin Van Buren by Henry Inman, circa 1840 Library of Congress Figure 1.3. Photograph of the elderly Martin Van Buren, between 1840 and 1862 Library of Congress Figure 1.4. James Leath and John Watson of the Columbia County Historical Society Photograph MAVA Collection Figure 2.1. -

![1935-12-01 [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1404/1935-12-01-p-601404.webp)

1935-12-01 [P ]

Soda. "I I Features for I Capita., S°g.ETY JECTI°^. ^ H;gh Li^ts 1 ^UttdatJ PtSlf W°men Prrt 3—14 Page* "j"_WASHINGTON, D. C., SUNDAY MORNING, DECEMBER 1, 1935._ Attractive Families Lend Interest to Society in the Nation’s Capital Mrs. Francis L. Spalding, daughter of the Minister of Austria, Mr. Edgar Mrs. Emmet C. Gudger, wife of Capt. Gudger, U. S. N., with their daughters. Ellen (right) and Gloria. Mrs. Harry D. Hummer, jr., with Yvonne Ruth, wife and daughter of Lieut, Prochnik, with her children, Loranda and Francis L. in Lieut, and Mrs. Stephanie Spalding, jr. is on at the navy Mrs. is the daughter of the late Senator Thomas J. Hummer, who is note on duty at the navy yard this city. Mr. and Mrs. and their children are the in Capt. Gudger duty yard* Gudger Spalding visiting former's parents — —B»cbr»cb rboto. Hams-**m* mmo. Boston. —Hessler-Henderson Photo Walsh of Montana, and uas her father’s official hostess for some time. Hummer make their home at 3600 Connecticut avenue. —----" --* <r Capital’s Little Season Miss Mary Cooke Bride Gay, With Debutantes Of George L. Jones, Jr., Holding Center of Stage In Cathedral Wedding President and Mrs. Roosevelt to Inaugurate Miss Mary Dunn Is Married to Mr. James Official Social Festivities With Cabinet Dennis Gable—Many Other Charming: Dinner December 11. Ceremonies Are Held. Thanksgiving now being a holiday nac, N. Y„ having lived In Washing- Residential circles In Washington i velvet, a coronet of tunc and carried of the past, society turns its attention ton for many years after their mar- are interested in the wedding of Miss a bouquet of white chrysanthemums. -

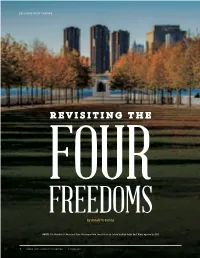

REVISITING the FOUR FREEDOMS by Donald M

EXCLUSIVE MCUF FEATURE REVISITING THE FOUR FREEDOMS By Donald M. Bishop PHOTO: The Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, located on an island in New York's East River, opened in 2012 3 • MARINE CORPS UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION • SUMMER 2019 EXCLUSIVE MCUF FEATURE Modern political warfare now includes both cyber and information operations. At MCU, Bren Chair of Strategic Communications Donald Bishop focuses his teaching and presentations on the “information” or “influence” dimension of conflict – disinformation, propaganda, persuasion, hybrid warfare – now enabled by the internet and social media. And he emphasizes that Americans, as they confront violent extremism and other threats, must know and be confident of the American values they defend. "Thanks, Grandpa, for coming to my game." Why look back at The Four Freedoms? First, in my classes at Marine Corps University, I’ve discovered that the current "I enjoyed it too, Jack. We men in our eighties don't get generation of Marines have never heard of them. Of Norman out as often as we wish. Seeing you score a run was Rockwell’s four famous paintings, they have seen only one – something. But you know, I noticed something else today. the family at Thanksgiving – and they don’t know they were "When you were at the plate, it carried me back to part of a series. Second – when Americans must articulate watching my older brother in the batter's box. You held the “what we’re for” (rather than “what we’re against”) – whether bat like he did. You have the same stance and the same in the war on terrorism or in a future of great power competi- swing. -

October 2011 2011 Fall Forums Explored “FDR’S Inner Circle”

Onnews and notes from Our the franklin d. roosevelt presidential Way library and museum with support from the Roosevelt Institute Online “Day by Day” Chronology Launched FDR PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY n October 15, 2011 the Pare Lorentz A searchable database based primarily on these OCenter at the FDR Library launched a calendar sources is available so that you can new online database of President Roosevelt’s search the chronology by keyword and date. daily schedule: “Franklin D. Roosevelt Day by Day,” www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/daybyday. As a fulfillment of Pare Lorentz’s original vision, Day by Day also includes an interactive timeline The Franklin D. Roosevelt Day by Day Project of additional materials from the Archives of the is an interactive chronology documenting FDR Library to place each day’s calendar into Franklin Roosevelt’s daily schedule as President, larger historical context. These materials include from March 1933 to April 1945. The project scanned photographs, letters and speeches as was inspired by the work of Pare Lorentz, a well as descriptions of events in United States Depression era documentary filmmaker, who and world history. Special thanks to former dedicated much of his life to documenting Roosevelt Library Director Verne Newton FDR’s daily activities as president, and is whose vision and determination started the Day supported by a grant from the New York by Day Project and helped secure the original Community Trust to the Pare Lorentz Center. funding for the Pare Lorentz Center. Day by Day features digitized original calendars ONLINE RESOURCES “Day by Day” website and schedules maintained by the White House These calendars trace FDR’s appointments, Pare Lorentz Center website Usher and the official White House stenographer. -

October 5, 2019

THE FOUR FREEDOMS AWARDS THE ROOSEVELT INSTITUTE The Four Freedoms Awards are presented to individuals and organizations whose Presents achievements have demonstrated a commitment to the principles which President Roosevelt proclaimed in his historic speech to Congress on January 6, 1941, as essential to democracy: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, freedom from fear. The Roosevelt Institute has awarded the Four Freedoms Medals to some of the most distinguished Americans and world citizens of our time, including Presidents Truman, Carter, and Clinton; Nelson Mandela; Coretta Scott King; Arthur Miller; Desmond Tutu; and the Honorable Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The Four Freedoms Awards are presented in alternating years by the Roosevelt Institute in the U.S. and Roosevelt Stichting in the Netherlands. We are honored to host a delegation of guests from the Netherlands in Hyde Park for the 2019 awards. THE ROOSEVELT INSTITUTE Until economic and social rules work for all Americans, they’re not working. Inspired by the legacy of Franklin and Eleanor, the Roosevelt Institute reimagines the rules to create a nation where everyone enjoys a fair share of our collective prosperity. OCTOBER 5, 2019 We are a 21st century think tank, bringing together multiple generations of thinkers and leaders to help drive key economic and social debates and have local and national impact. The Roosevelt Institute is also the nonprofit partner to the FDR Presidential Library and Museum. THE FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum is America’s first presidential library—and the only one used by a sitting president.