Last Month When I Was Watching the Chris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage

The Constitutional Requirements for the Royal Morganatic Marriage Benoît Pelletier* This article examines the constitutional Cet article analyse les implications implications, for Canada and the other members of the constitutionnelles, pour le Canada et les autres pays Commonwealth, of a morganatic marriage in the membres du Commonwealth, d’un mariage British royal family. The Germanic concept of morganatique au sein de la famille royale britannique. “morganatic marriage” refers to a legal union between Le concept de «mariage morganatique», d’origine a man of royal birth and a woman of lower status, with germanique, renvoie à une union légale entre un the condition that the wife does not assume a royal title homme de descendance royale et une femme de statut and any children are excluded from their father’s rank inférieur, à condition que cette dernière n’acquière pas or hereditary property. un titre royal, ou encore qu’aucun enfant issu de cette For such a union to be celebrated in the royal union n’accède au rang du père ni n’hérite de ses biens. family, the parliament of the United Kingdom would Afin qu’un tel mariage puisse être célébré dans la have to enact legislation. If such a law had the effect of famille royale, une loi doit être adoptée par le denying any children access to the throne, the laws of parlement du Royaume-Uni. Or si une telle loi devait succession would be altered, and according to the effectivement interdire l’accès au trône aux enfants du second paragraph of the preamble to the Statute of couple, les règles de succession seraient modifiées et il Westminster, the assent of the Canadian parliament and serait nécessaire, en vertu du deuxième paragraphe du the parliaments of the Commonwealth that recognize préambule du Statut de Westminster, d’obtenir le Queen Elizabeth II as their head of state would be consentement du Canada et des autres pays qui required. -

English, French, and Spanish Colonies: a Comparison

COLONIZATION AND SETTLEMENT (1585–1763) English, French, and Spanish Colonies: A Comparison THE HISTORY OF COLONIAL NORTH AMERICA centers other hand, enjoyed far more freedom and were able primarily around the struggle of England, France, and to govern themselves as long as they followed English Spain to gain control of the continent. Settlers law and were loyal to the king. In addition, unlike crossed the Atlantic for different reasons, and their France and Spain, England encouraged immigration governments took different approaches to their colo- from other nations, thus boosting its colonial popula- nizing efforts. These differences created both advan- tion. By 1763 the English had established dominance tages and disadvantages that profoundly affected the in North America, having defeated France and Spain New World’s fate. France and Spain, for instance, in the French and Indian War. However, those were governed by autocratic sovereigns whose rule regions that had been colonized by the French or was absolute; their colonists went to America as ser- Spanish would retain national characteristics that vants of the Crown. The English colonists, on the linger to this day. English Colonies French Colonies Spanish Colonies Settlements/Geography Most colonies established by royal char- First colonies were trading posts in Crown-sponsored conquests gained rich- ter. Earliest settlements were in Virginia Newfoundland; others followed in wake es for Spain and expanded its empire. and Massachusetts but soon spread all of exploration of the St. Lawrence valley, Most of the southern and southwestern along the Atlantic coast, from Maine to parts of Canada, and the Mississippi regions claimed, as well as sections of Georgia, and into the continent’s interior River. -

The Governor Genera. and the Head of State Functions

The Governor Genera. and the Head of State Functions THOMAS FRANCK* Lincoln, Nebraska In most, though by no means all democratic states,' the "Head o£ State" is a convenient legal and political fiction the purpose of which is to personify the complex political functions of govern- ment. What distinguishes the operations of this fiction in Canada is the fact that the functions of head of state are not discharged by any one person. Some, by legislative enactment, are vested in the Governor General. Others are delegated to the Governor General by the Crown. Still others are exercised by the Queen in person. A survey of these functions will reveal, however, that many more of the duties of the Canadian head of state are to-day dis- charged by the Governor General than are performed by the Queen. Indeed, it will reveal that some of the functions cannot be dis- charged by anyone else. It is essential that we become aware of this development in Canadian constitutional practice and take legal cognizance of the consequently increasing stature and importance of the Queen's representative in Canada. Formal Vesting of Head of State Functions in Constitutional Governments ofthe Commonnealth Reahns In most of the realms of the Commonwealth, the basic constitut- ional documents formally vest executive power in the Queen. Section 9 of the British North America Act, 1867,2 states: "The Executive Government and authority of and over Canada is hereby declared to continue and be vested in the Queen", while section 17 establishes that "There shall be one Parliament for Canada, consist- ing of the Queen, an Upper House, styled the Senate, and the *Thomas Franck, B.A., LL.B. -

“An Audience with the Queen”: Indigenous Australians and the Crown, 1854-2017

2018 V “An audience with the Queen”: Indigenous Australians and the Crown, 1854-2017 Mark McKenna Article: “An audience with the Queen”: Indigenous Australians and the Crown, 1954-2017 “An audience with the Queen”: Indigenous Australians and the Crown, 1954- 2017 Mark McKenna Abstract: This article is the first substantial examination of the more recent historical relationship between Indigenous Australians and the Crown. While the earlier tradition of perceiving the Queen as benefactress has survived in Indigenous communities, it now co- exists with more critical and antagonistic views. After the High Court’s Mabo decision (1992), the passage of the Native Title Act (1993), and the federal government’s Apology to the Stolen Generations (2008), it is clear that the only avenues for seriously redressing Indigenous grievances lie within the courts and parliaments of Australia. The Australian monarch—either as a supportive voice, or as a vehicle for highlighting the failure of Australian governments— no longer holds any substantial political utility for Indigenous Australians. Monarchy has become largely irrelevant to the fate of future Indigenous claims for political and social justice. Keywords: monarchy, republic, Indigenous Australia n October 1999, a delegation of Indigenous leaders from Australia visited Queen Elizabeth II at Buckingham Palace. The ‘audience,’ which lasted for little more than an hour and was widely reported in the British and Australian press, was claimed to Ibe the first granted to Indigenous Australians by a reigning British monarch since 24 May 1793, when Bennelong, who had been captured by Governor Arthur Phillip in Sydney and later sailed with him to England, was presented to King George III.1 The 206-year hiatus was telling for more than one reason. -

The Current Status and Issues Surrounding Native Title in Regional Australia

284 Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, Vol. 24, No 3, 2018 NEW DIMENSIONS IN LAND TENURE – THE CURRENT STATUS AND ISSUES SURROUNDING NATIVE TITLE IN REGIONAL AUSTRALIA Jude Mannix PhD Candidate, Science and Engineering Faculty, School of Civil Engineering and Built Environment, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, 4000, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Michael Hefferan Emeritus Professor, c/- Science and Engineering Faculty, School of Civil Engineering and Built Environment, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, 4000, Australia. Email: [email protected]. ABSTRACT: The acquisition and use of real property is fundamental to practically all types of resource and infrastructure projects. The success of those activities is based, in no small way, on the reliability of the underlying tenure and land management systems operating across all Australian states and territories. Against that background, however, the historic Mabo (1992) decision gave recognition to Indigenous land rights and the subsequent enactment of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth.) (NTA) ushered in an emerging and complex new aspect of property law. While receiving wide political and community support, these changes have had a significant effect on those long-established tenure systems. Further, it has only been over time, as diverse property dealings have been encountered, that the full implications of the new legislation and its operations have become clear. Regional areas are more likely to encounter native title issues than are urban environments due, in part, to the presence of large scale agricultural and pastoral tenures and of significant areas of un-alienated crown land, where native title may not have been extinguished. -

The Sovereign and Parliament

Library Note The Sovereign and Parliament The Sovereign fulfils a number of ceremonial and formal roles with respect to Parliament, established by conventions, throughout the parliamentary calendar. The State Opening of Parliament marks the beginning of each new session of Parliament. It is the only routine occasion when the three constituent parts of Parliament—that is the Sovereign, the House of Lords and the House of Commons—meet. The Queen’s Speech during State Opening is the central element around which the ceremony pivots, without which no business of either the House of Lords or the House of Commons can proceed. Each ‘Parliament’ lasts a maximum of five years, within which there are a number of sessions. Each session is ‘prorogued’ to mark its end. An announcement is made in the House of Lords, to Members of both Houses following the Queen’s command that Parliament should be prorogued by a commissioner of a Royal Commission. At the end of the final session of each Parliament—which is immediately prior to the next general election—Parliament is also dissolved. Following the Prime Minister’s advice, the Sovereign issues a proclamation summoning the new Parliament, appointing the day for the first meeting of Parliament. All bills must be agreed by both Houses of Parliament and the Sovereign before they can become Acts of Parliament. Once a bill has passed both Houses, it is formally agreed by the Sovereign by a process known as royal assent. Additionally, Queen’s consent is sometimes required before a bill completes its passage through Parliament, if the bill affects the Sovereign. -

Scriptedpifc-01 Banijay Aprmay20.Indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights Presents… Bäckström the Hunt for a Killer We Got This Thin Ice

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | April/May 2020 Television e Interview Virtual thinking The Crown's Andy Online rights Business Harries on what's companies eye next for drama digital disruption TBI International Page 10 Page 12 pOFC TBI AprMay20.indd 1 20/03/2020 20:25 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. sadistic murder case that had remained unsolved for 16 years. most infamous unsolved murder case? climate change, geo-politics and Arctic exploitation. Bang The Gulf GR5: Into The Wilderness Rebecka Martinsson When a young woman vanishes without a trace In a brand new second season, a serial killer targets Set on New Zealand’s Waiheke Island, Detective Jess Savage hiking the famous GR5 trail, her friends set out to Return of the riveting crime thriller based on a group of men connected to a historic sexual assault. investigates cases while battling her own inner demons. solve the mystery of her disappearance. the best-selling novels by Asa Larsson. banijayrights.com ScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay AprMay20.indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. -

House of Lords Reform 1997–2010: a Chronology

House of Lords Reform 1997–2010: A Chronology This House of Lords Library Note sets out in summary form the principal developments in House of Lords reform under the Labour Government of 1997–2010. Chris Clarke and Matthew Purvis 28th June 2010 LLN 2010/015 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 1997 .................................................................................................................................. 2 1998 .................................................................................................................................. 2 1999 .................................................................................................................................. 3 2000 .................................................................................................................................. 4 2001 .................................................................................................................................. 5 2002 ................................................................................................................................. -

Table of Contents Chronology of Events

Table of Contents Chronology of Events .............................................................................................................................................................. 4 History- 1788 to 1900 .............................................................................................................................................. 5 Plenary ‘sovereign’ Parliaments ........................................................................................................................................ 5 History- Towards Federation- 1880 to 1990 ................................................................................................... 6 Federation (1901)...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (Imp) ...................................................................................... 7 Post Federation- 1901 to 1986 (Parliamentary Sovereignty) ................................................................... 8 ‘Balfour Declaration 1926’ [1.3.9E] .................................................................................................................................. 8 Statute of Westminster 1931 (UK) [1.3.11E] ................................................................................................................ 8 The Australia Acts .................................................................................................................................................................. -

ROYAL—All but the Crown!

The emily Dickinson inTernaTional socieTy Volume 21, Number 2 November/December 2009 “The Only News I know / Is Bulletins all Day / From Immortality.” emily dickinson in20ternation0al so9ciety general meeting EMILY DICKINSON: ROYA L — all but the Crown! Queen Without a Crown July –August , , Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada eDis 2009 annual meeTing Eleanor Heginbotham with Beefeater Guards Emily with Beefeater Guards Suzanne Juhasz, Jonnie Guerra, and Cris Miller with Beefeater Guards Cindy MacKenzie and Emily Special Tea Cake Paul Crumbley, EDIS president and Cindy MacKenzie, organizer of the 2009 Annual Meeting Georgie Strickland, former editor of the Bulletin Bill and Nancy Pridgen, EDIS members George Gleason, EDIS member and Jane Wald, executive director of the Emily Dickinson Museum Jane Eberwein, Gudrun Grabher, Vivian Pollak, Martha Ackmann and Ann Romberger at banquet Group in front of the Provincial Government House and Eleanor Heginbotham at banquet Cover Photo Courtesy of Emily Seelbinder Photos Courtesy of Eleanor Heginbotham and Georgie Strickland I n Th I s Is s u e Page 3 Page 12 Page 33 F e a T u r e s r e v I e w s 3 Queen Without a Crown: EDIS 2009 19 New Publications Annual Meeting By Barbara Kelly, Book Review Editor By Douglas Evans 24 Review of Jed Deppman, Trying to Think with Emily Dickinson 6 Playing Emily or “the welfare of my shoes” Reviewed by Marianne Noble By Barbara Dana 25 Review of Elizabeth Oakes, 9 Teaching and Learning at the The Luminescence of All Things Emily Emily Dickinson Museum Reviewed by Janet -

Queen's Or Prince's Consent

QUEEN’S OR PRINCE’S CONSENT This pamphlet is intended for members of the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel. Unless otherwise stated: • references to Erskine May are to the 24th edition (2011), • references to the Companion to the Standing Orders are to the Companion to the Standing Orders and Guide to Proceedings of the House of Lords (25th edition, 2017), • references to the Cabinet Office Guide to Making Legislation are to the version of July 2017. Office of the Parliamentary Counsel September 2018 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 2 QUEEN’S CONSENT Introduction. 2 The prerogative. 2 Hereditary revenues, the Duchies and personal property and interests . 4 Exceptions and examples . 6 CHAPTER 3 PRINCE’S CONSENT Introduction. 7 The Duchy of Cornwall . 7 The Prince and Steward of Scotland . 8 Prince’s consent in other circumstances . 8 Exceptions and examples . 8 CHAPTER 4 GENERAL EXCEPTIONS The remoteness/de minimis tests . 10 Original consent sufficient for later provisions . 10 No adverse effect on the Crown. 11 CHAPTER 5 THE SIGNIFICATION OF CONSENT Signification following amendments to a bill. 13 Re-signification for identical bill . 14 The manner of signification . 14 The form of signification . 15 CHAPTER 6 PRACTICAL STEPS Obtaining consent. 17 Informing the Whips . 17 Writing to the House authorities . 17 Private Members’ Bills. 17 Informing the Palace of further developments . 18 Other. 18 CHAPTER 7 MISCELLANEOUS Draft bills . 19 Consent not obtained . 19 Inadvertent failure to signify consent . 19 Consent in the absence of the Queen. 20 Consent before introduction of a bill . 20 Queen’s speech . 20 Royal Assent . -

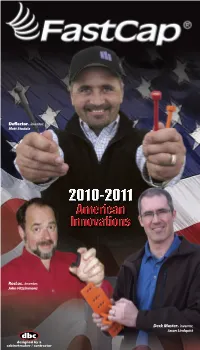

Fastcap 21-30

DeflectorTM inventor, Matt Stodola RocLocTM inventor, John Fitzsimmons Deck MasterTM inventor, Jason Lindquist dbc designed by a cabinetmaker / contractor PRO Tools VLRQDO RIHV JUDG SU H Artisan Accents TM JUHDWSULFH & Mortise Tool Turn of the century craftsmanship with the tap of a hammer. Available in three sizes: 5/16”, 3/8” and 2”, create a beautiful ebony pinned look with the Mortise ToolTM and Artisan AccentsTM. Combining the two allows you to create the look of Greene & Greene furniture in a fraction of the time. Everyone will think you spent hours using ebony pins, flush cut saws and meticulously sanding. “Stop The StruggleTM” 1. Identify where the pin needs to go and tap with the Mortise ToolTM to make the Get the “Greene & Greene” look Accent divots. 2. Install a trim screw, if using one (it is not necessary; the Accents can simply be decorative). 3. Align the Artisan AccentTM in the divots, tap with a hammer until the edge of the Artisan AccentTM is flush with the edge of the wood and you are done! Note: Apply a dab of 2P-10TM Jël under the Artisan AccentTM for a permanent hold. Fast & simple! The 2” Artisan Chisel on an air hammer leaves a perfect outline for the Accents. The Artisan Accent tools are intended for use in real wood Great for... applications. Not recommended • Furniture • Beams for use on man-made material. • Cabinets • Rafters • Trim • Decks • and more! A Pocket Chisel creates square corners for the accent 2” 5 ⁄16” A small dab of 2P-10 Jël in the corners locks the Accent in place 3 ⁄8” Patent Pending Description Part Number USD Artisan Accents (50 pc) 5/16” ARTISAN ACCENT 5/16 $5.00 Mortise Tool (5/16”) MORTISE TOOL 5/16 $20.00 Artisan Accents (50 pc) 3/8” ARTISAN ACCENT 3/8 $5.00 Mortise Tool (3/8”) MORTISE TOOL 3/8 $20.00 Inventor, Artisan Accents (10 pc) 2” ARTISAN ACCENT 2 $9.99 Jeff Marholin Artisan Chisel 2” ARTISAN CHISEL 2 $59.99 A fi nished professional look dbc designed by a cabinetmaker www.fastcap.com 21 PRO Tools TM *Four corners shown Screw the Ass.