Pakistan's Third Democratic Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan's Institutions

Pakistan’s Institutions: Pakistan’s Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Work They But How Can Matter, They Know We Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman and Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Essays by Madiha Afzal Ishrat Husain Waris Husain Adnan Q. Khan, Asim I. Khwaja, and Tiffany M. Simon Michael Kugelman Mehmood Mandviwalla Ahmed Bilal Mehboob Umar Saif Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain ©2018 The Wilson Center www.wilsoncenter.org This publication marks a collaborative effort between the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars’ Asia Program and the Fellowship Fund for Pakistan. www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program fffp.org.pk Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 Cover: Parliament House Islamic Republic of Pakistan, © danishkhan, iStock THE WILSON CENTER, chartered by Congress as the official memorial to President Woodrow Wilson, is the nation’s key nonpartisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue to inform actionable ideas for Congress, the Administration, and the broader policy community. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. -

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

U A Z T m B PEACEWA RKS u E JI Bulunkouxiang Dushanbe[ K [ D K IS ar IS TA TURKMENISTAN ya T N A N Tashkurgan CHINA Khunjerab - - ( ) Ind Gilgit us Sazin R. Raikot aikot l Kabul 1 tro Mansehra 972 Line of Con Herat PeshawarPeshawar Haripur Havelian ( ) Burhan IslamabadIslamabad Rawalpindi AFGHANISTAN ( Gujrat ) Dera Ismail Khan Lahore Kandahar Faisalabad Zhob Qila Saifullah Quetta Multan Dera Ghazi INDIA Khan PAKISTAN . Bahawalpur New Delhi s R du Dera In Surab Allahyar Basima Shahadadkot Shikarpur Existing highway IRAN Nag Rango Khuzdar THESukkur CHINA-PAKISTANOngoing highway project Priority highway project Panjgur ECONOMIC CORRIDORShort-term project Medium and long-term project BARRIERS ANDOther highway IMPACT Hyderabad Gwadar Sonmiani International boundary Bay . R Karachi s Provincial boundary u d n Arif Rafiq I e nal status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed upon Arabian by India and Pakistan. Boundaries Sea and names shown on this map do 0 150 Miles not imply ocial endorsement or 0 200 Kilometers acceptance on the part of the United States Institute of Peace. , ABOUT THE REPORT This report clarifies what the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor actually is, identifies potential barriers to its implementation, and assesses its likely economic, socio- political, and strategic implications. Based on interviews with federal and provincial government officials in Pakistan, subject-matter experts, a diverse spectrum of civil society activists, politicians, and business community leaders, the report is supported by the Asia Center at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). ABOUT THE AUTHOR Arif Rafiq is president of Vizier Consulting, LLC, a political risk analysis company specializing in the Middle East and South Asia. -

6455.Pdf, PDF, 1.27MB

Overall List Along With Domicile and Post Name Father Name District Post Shahab Khan Siraj Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sana Ullah Muhammad Younas Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Mahboob Ali Fazal Rahim Swat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tahir Saeed Saeed Ur Rehman Kohat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Owais Qarni Raham Dil Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Ashfaq Ahmad Zarif Khan Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Saud Khan Haji Minak Khan Khyber 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Qamar Jan Syed Marjan Kurram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Kamil Khan Wakeel Khan PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Waheed Gul Muhammad Qasim Lakki Marwat 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Tanveer Ahmad Mukhtiar Ahmad Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Faheem Muhammad Aslam PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muslima Bibi Jan Gul Dera Ismail Khan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Muhammad Zahid Muhammad Saraf Batagram 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Riaz Khan Muhammad Anwar Lower Dir 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Bakht Taj Abdul Khaliq Shangla 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Hidayat Ullah Fazal Ullah Swabi 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Wajid Ali Malang Jan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Sahar Rashed Abdur Rasheed Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Afsar Khan Afridi Ghulam Nabi PESHAWAR 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Khan Manazir Khan Mardan 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Liaqat Ali Malik Aman Charsadda 01. Station House Incharge (BPS-16) Adnan Iqbal Parvaiz Khan Mardan 01. -

Download Report

Pakistan: AnAn EvaluationEvaluation ofof thethe WorldWorld Bank’sBank’s AssistanceAssistance The World Bank Group WORKING FOR A WORLD FREE OF POVERTY The World Bank Group consists of five institutions—the International Bank for Reconstruc- tion and Development (IBRD), the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the International Development Association (IDA), the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), and the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID). Its mission is to fight poverty for lasting results and to help people help themselves and their environment by providing resources, sharing knowledge, building capacity, and forging partnerships in the public and private sectors. The Independent Evaluation Group ENHANCING DEVELOPMENT EFFECTIVENESS THROUGH EXCELLENCE AND INDEPENDENCE IN EVALUATION The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) is an independent, three-part unit within the World Bank Group. IEG-World Bank is charged with evaluating the activities of the IBRD (The World Bank) and IDA, IEG-IFC focuses on assessment of IFC’s work toward private sector development, and IEG-MIGA evaluates the contributions of MIGA guarantee projects and services. IEG reports directly to the Bank’s Board of Directors through the Director-General, Evaluation. The goals of evaluation are to learn from experience, to provide an objective basis for assess- ing the results of the Bank Group’s work, and to provide accountability in the achievement of its objectives. It also improves Bank Group work by identifying and disseminating the lessons learned from experience and by framing recommendations drawn from evaluation findings. Pakistan: An Evaluation of the World Bank’s Assistance 2006 The World Bank http://www.worldbank.org/ieg Washington, D.C. -

Copy of PEC Website Data AR 17.Xlsx

List of Candidates Selected for PTS Test - (Assistant Registrar PEC-17) SR# Candidate Name Father Name CNIC Domicile PEC Registration No Test Centre 1 Nasir Ali Sahib Gul 1610117293283 KPK Elect/29852 Peshawar 2 Inamullah Noor Ullah 5130194700391 Balochistan Civil/46740 Lahore 3 Ali Raza Ali Gul Abbasi 4550103452541 sindh Chem/14074 Lahore 4 Mussadiq Khan Jam Mitha Khan 4520396621829 Sindh Civil/49345 Karachi 5 Waseem Haider Ghulam Haider Khokhar 4320493016341 Sindh Elect/51822 Karachi 6 Muhammad Fida Masood Masood Ur Rehman 6110118422435 KPK Mech/36822 Islamabad 7 Waseem Sarwar Soomro Ghulam Sarwar Soomro 4140925493889 Sindh Petgas/01673 Karachi 8 Muhammad Sajid Ali Muhammad Bakhsh 3310685514621 Punjab Elect/52922 Lahore 9 Rahim Dad Gul Dad Khan 1110105410761 KPK Mining/01742 Peshawar 10 Muhammad Zubair Habib Ullah Khan 1420147509873 KPK Elect/64187 Peshawar 11 Sayed Yahya Shah Ali Asghar Shah 4530278512303 Sindh Electro/19721 Karachi 12 Raja Ahsan Waqas Muhammad Tariq 1730194169921 KPK Elect/38075 Peshawar 13 Muhammad Bilal Habib Ullah Khan 1420101553861 KPK Elect/44842 Peshawar 14 Raza Ullah Lodhi Zafar Ullah Khan Lodhi 813022864501 AJK Elect/49162 Islamabad 15 Arshad Karim Muhammad Karim 1430173275221 KPK Mechatro/1096 Peshawar 16 Muhammad Naqi Syed Mazhar-Ul-Hassan 3320216590959 Punjab Elect/42183 Islamabad 17 Muhammad Imran Uddin Khan Muhammad Asrar Uddin Khan 4210154896239 Sindh Metal/04701 Karachi 18 Khurram Akram Sheikh Muhammad Akram Shaikh 4240110279493 Sindh Elect/22791 Karachi 19 Rana Talha Naeem Rana Naeem Ahmad 3650281778249 -

Dr. Salman Shah Dr. Salman Shah Was the Former Caretaker Finance Minister of Pakistan. He Has Also Served As an Advisor to the F

Dr. Salman Shah Dr. Salman Shah was the former caretaker Finance Minister of Pakistan. He has also served as an advisor to the Finance Minister Shaukat Aziz on finance, economic affairs, statistics and revenues. He is the son-in-law of former Chief of Army Staff General Asif Nawaz Janjua. He has two sons and three daughters. Dr. Shah, a Lahore based Economist, holds a PhD in Finance and Economics from Indiana University, Bloomington's Kelley School of Business. He has 16 years of teaching experience at institutions such as University of Michigan, Indiana University, University of Toronto, and Lahore University of Management Sciences. He is one of the most highly educated and competent members of Shaukat Aziz's team. During his time as in charge of Pakistan's finance ministry (2004-2008), Pakistan's economy registered an average of 7% GDP growth per annum, one of the highest in the world. Prior to his appointment as Finance Minister, he has served on following positions:- Economic consultant, to different Pakistani governments including that of Nawaz Sharif. Chairman of Privatization Commission during the tenure of caretaker government of Prime Minister Malik Merai Khalid. Member, Board of Governors -.Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS). Member, Board of Directors - Pakistan International Airlines. Member, Central Board of Directors - State Bank of Pakistan (2002-2003) Member, of various government's task forces. Dr. Shah was also appointed as a member of the task force on investment by Abdul Hafeez Sheikh which gave recommendations to the Board of Investment to increase investments in the country. Shah headed the regional task forces of Karachi and Lahore regions for the BoI under Hafeez Dr. -

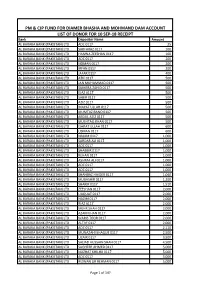

Pm & Cjp Fund for Diamer Bhasha and Mohmand Dam

PM & CJP FUND FOR DIAMER BHASHA AND MOHMAND DAM ACCOUNT LIST OF DONOR FOR 10 SEP-18 RECEIPT Bank Depositor Name Amount AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ADC 0117 25 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SARFARAZ 0117 100 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD HAMNA ZEESHAN 0117 100 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ADC 0117 200 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD NOMAN 0117 200 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD IRFAN 0117 200 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD JAFAR 0117 400 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ATIF 0117 500 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD JAN MUHAMMAD 0117 500 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SUMERA ZAHID 0117 500 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD EJAZ 0117 500 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SABIR 0117 500 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD AZIZ 0117 500 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD INAYAT ULLAH 0117 500 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD MUMTAZ BANO 0117 500 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ABDUL AZIZ 0117 500 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD MUSHTAQ KHAN 0117 500 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ISHRAT ULLAH 0117 600 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD USMAN 0117 600 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD NAJAM 0117 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SARDAR ALI 0117 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ADC 0117 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SHABBIR 0117 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD REHAN 0117 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ASHRAF ALI 0117 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ADC 0117 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD ADC 0117 1,000 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SHAHBAZ HAIDER 0117 1,040 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD MUBASHIR 0117 1,200 AL BARAKA BANK (PAKISTAN) LTD SHAKIR 0117 1,510 AL -

Speech of Mr. Shaukat Aziz

Speech on the occasion of dinner hosted in honour of Mr. Shaukat Aziz on December 14, 2007 When I look back on over 76 years of my life, I can clearly identify milestones as coincidences, which influenced my life. My mother’s demise even before I reached the age of two years and my father’s remarrying in her life time leading to my maternal grandfather’s decision to bring me up. It used to be said in those days that the Indian Civil Service was neither Indian nor civil nor a service. However, my upbringing in a civil servant’s household holding the position of a Deputy Commissioner in many districts of what in those days was United Provinces or UP was devoid of arrogance instead was imbued with qualities and values of honesty, integrity and compassion. My grandfather became my role model and I have throughout my life, tried to emulate him. My dream was to join the civil service and be like my grandfather and when hurdles came in my way to achieving my objective after qualifying in the Central Superior Services of Pakistan competitive examination, Dr. Khan Sahib brother of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan testified to my being genuinely domiciled in NWFP through marital ties, although my father-in-law Dr. Abdur Rahim, a lawyer by profession, was known opponent of his policies as he was of Khan Abdul Qayyum Khan against whom with likeminded friends he filed a PRODA in 1953 for corruption and got him removed from the post of NWFP Chief Minister. My father-in-law remained opposed to all governments in power irrespective of the parties they belonged to. -

FUELING the FUTURE: Meeting Pakistan’S Energy Needs in the 21St Century

FUELING THE FUTURE: Meeting Pakistan’s Energy Needs in the 21st Century Edited by: Robert M. Hathaway Bhumika Muchhala Michael Kugelman FUELING THE FUTURE: Meeting Pakistan’s Energy Needs in the 21st Century FUELING THE FUTURE: Meeting Pakistan’s Energy Needs in the 21st Century Essays by: Mukhtar Ahmed Saleem H. Ali Shahid Javed Burki John R. Hammond Dorothy Lele Robert Looney Sanjeev Minocha Bikash Pandey Sabira Qureshi Asad Umar Vladislav Vucetic and Achilles G. Adamantiades Aram Zamgochian Edited by: Robert M. Hathaway Bhumika Muchhala Michael Kugelman March 2007 Available from : Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 www.wilsoncenter.org ISBN 1-933549-17-3 Cover photos: Water Rushes Through the Warsak Dam, Pakistan, © Paul Almasy/CORBIS; Woodcutter in Hunza Valley, © Robert Holmes/CORBIS The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, established by Congress in 1968 and headquartered in Washington, D.C., is a living national memorial to President Wilson. The Center’s mission is to commemorate the ideals and concerns of Woodrow Wilson by pro- viding a link between the worlds of ideas and policy, while fostering research, study, discussion, and collaboration among a broad spectrum of individuals concerned with policy and scholarship in national and international affairs. Supported by public and private funds, the Center is a nonpartisan institution engaged in the study of national and world affairs. It establishes and maintains a neutral forum for free, open, and informed dialogue. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publi- cations and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advi- sory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center.