Download Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical Dentistry Candidate Name Father's Name Seherish Khan Abbasi Muhammad Khurshid Hiba Naeem Muhammad Naeem Khan Azmaira

CLINICAL DENTISTRY CANDIDATE NAME FATHER’S NAME SEHERISH KHAN ABBASI MUHAMMAD KHURSHID HIBA NAEEM MUHAMMAD NAEEM KHAN AZMAIRA MUHAMMAD SHOAIB DR AAMIRA JAWED DR JAWED AKHTER ALEENA SYED SHAHERYAR SADIQ DR KOMAL SHAHZAD NADEEM SHAHZAD SABA ARSHAD MOHAMMAD OMER MUHAMMAD AHSAN SHAHZAD SOHAIL SHAHZAD NOOR UL AIN MEHAK MOHI UD DIN SIDDIQUI HAREEM SULTAN SYED ALI ARSALAN FARHINA MAZHAR MUHAMMAD MAZHAR SULTAN HIBA TABASSUM MUHAMMAD HANIF MAHAVOSH QAZI TARIQ QAZI RAO MUHAMMAD HAYAT ABDUL NASIR RAJPUT MUHAMMAD ZOHAIB YOUNUS MUHAMMAD YOUNUS ABDUL HAFEEZ NOOR MUHAMMAD SYED WAHIB ASIF ZAIDI SYED ASIF ZAFAR ZAIDI AHSAN ALI GHULAM MUSTAFA DR.FIZZA KHALID KHALID SALEEM FATIMA ISRAR CDR. ISRAR UL HAQ DR. AYESHA BUGTI SHABBIR AHMED MUHAMMAD WALEED VOHRA MUHAMMAD YOUSUF SHAHERYAR JAVED IQBAL JAVED IQBAL YOUSUF SHEENA NANDLAL DR. WASFA RASHEED RASHEED AHMAD KHAN SADAF SAEED SYED MUZAFFAR SAEED AYESHA DOSSANI MATEEN YAHYA DR. ARIF SOOMRO SHER MOHAMMAD NOMAN HUSSAIN HUSSAIN BADSHAH AISHA NAVEED MARIAM SHAFIQ SHAFIQ AHMED DR.MARIA MUHAMMAD SHABBIR SHAHID ISLAM MUHAMMAD ISLAM SAMAR SULTAN MUHAMMAD SULTAN DR. SADIA NAZIR DR.ARIF AEYMAN AHMED SHAKEEL AHMED AKHTAR ALI MEER HAWAS KHAN SHIZA MUJTABA GHULAM MUJTABA KHAN REKHA RAMLAL MAJID HUSSAIN NIZAMUDDIN FATIMA ALI CHANNA COL.(R) DR. ALI DINO CHANNA DR.MARIA NAZ PROF.DR.QAZI JALAL UDIN AHMED AZAM MUHAMMAD ALIUDDIN MUHAMMAD ALIUDDIN NAZMINA JASANI RIAZ JASANI RAM PERSHAD CHOONI LAL SHARMA POORAN DR SANIA RIAZ RIAZUDDIN KHAN FAKEHA NAEEM M. NAEEM QURESHI CLINICAL DENTISTRY CANDIDATE NAME FATHER’S NAME AIMAN HABIB -

Tariq Bajwa: State Bank of Pakistan's 70Th Anniversary

Governor : Mr. Tariq Bajwa Title : SBP’s 70th Anniversary: Welcome Note by Governor SBP Date : July 01, 2018 Event : State Bank of Pakistan’s 70-year Celebration Event Venue : SBP Head Office Karachi. State Bank of Pakistan’s 70th Anniversary Welcome Note by Governor SBP Governor Sindh Mr. Zubair, Honorable Finance Minister, Dr Shamshad Akhtar, Respectable Former Governors, State Bank of Pakistan, Dr. Ishrat Husain, Mr. Yasin Anwar, Mr. Ashraf Wathra Distinguished guests, Ladies and Gentlemen, Assalam-o-aliakum and a very good morning! It is my pleasant duty and distinct privilege to welcome you all to the 70th anniversary of the establishment of State Bank of Pakistan. On the auspicious occasion of the opening of the SBP on July 1st, 1948, the Quaid said: “The opening of State Bank of Pakistan symbolizes the sovereignty of our state in the financial sphere. I need to hardly dilate on the important role the State Bank will have to play in regulating the economic life of our country. The monetary policy of the bank will have a direct bearing on our trade and commerce, both inside Pakistan as well as with the outside world and it is only to be desired that our policy should encourage maximum production and free flow of trade.” Page 1 of 4 The SBP as an institution has tried to live up to the expectations of the Quaid. From a modest beginning in borrowed premises, ladies and gentlemen, SBP rose to have earned the reputation of being a professional, progressive and forward-looking institution. The journey has been challenging, arduous, but rewarding. -

Volume VIII, Issue-3, March 2018

Volume VIII, Issue-3, March 2018 March in History Nation celebrates Pakistan Day 2018 with military parade, gun salutes March 15, 1955: The biggest contingents of armoured and mech - post-independence irrigation anised infantry held a march-past. project, Kotri Barrage is Pakistan Army tanks, including the inaugurated. Al Khalid and Al Zarrar, presented March 23 , 1956: 1956 Constitution gun salutes to the president. Radar is promulgates on Pakistan Day. systems and other weapons Major General Iskander Mirza equipped with military tech - sworn in as first President of nology were also rolled out. Pakistan. The NASR missile, the Sha - heen missile, the Ghauri mis - March 23, 1956: Constituent sile system, and the Babur assembly adopts name of Islamic cruise missile were also fea - Republic of Pakistan and first constitution. The nation is celebrating Pakistan A large number of diplomats from tured in the parade. Day 2018 across the country with several countries attended the March 8, 1957: President Various aeroplanes traditional zeal and fervour. ceremony. The guest of honour at Iskandar Mirza lays the belonging to Army Avi - foundation-stone of the State Bank the ceremony was Sri Lankan Pres - Pakistan Day commemorates the ation and Pakistan Air of Pakistan building in Karachi. ident Maithripala Sirisena. passing of the Lahore Resolution Force demonstrated aer - obatic feats for the March 23, 1960: Foundation of on March 23, 1940, when the All- Contingents of Pakistan Minar-i-Pakistan is laid. India Muslim League demanded a Army, Pakistan Air Force, and audience. Combat separate nation for the Muslims of Pakistan Navy held a march-past and attack helicopters, March 14, 1972: New education the British Indian Empire. -

Details of Unclaimed Insurance Benefits As at September 30, 2019

DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED INSURANCE BENEFITS AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 S.NO NAME 1 Iqbal Hussain Shaikh 2 Faisal Aziz 3 Khalid Mahmood 4 Kamal Khan Laghri 5 Haleema Bibi 6 Jamila Ali 7 Manzoor Ahmed Khokar 8 Faisal Cheema 9 Iqbal Hussain Lakho 10 Mohammad Ali 11 Mazher Mohib 12 Zahid Mehmood 13 Gulzar Hussain 14 Naushad 15 Farah Zeba 16 Shah Sikander 17 Bhagyou 18 Seema Jabeen 19 Imran Ilyas Jutt 20 Iqbal Khanani 21 Iqbal Khanani 22 Malik Nasrullah Jan 23 Anwar Mohammad Ali 24 Mohammad Aamir Ahmed 25 Mohammad Khalid Alvi 26 Hafiz Khalid Hussain 27 Muhammad Jandad 28 Nighat Kanwal Pervez 29 Abdul Hameed 30 Ameer Hamza 31 Shoaib Ali 32 Nasir Khan 33 Muhammad Darvesh Lakhan 34 Zameer Ahmed 35 Shabir Hussain Shah 36 Muhammad Israr 37 Shahzada Saeed Ahmed 38 Nabeela Saddiq Satti 39 Mansoorali DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED INSURANCE BENEFITS AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 S.NO NAME 40 Naeem Abbas 41 Abdul Kareem 42 Noor Ahmed Korejo 43 Muhammad Sadiq 44 Manzoor Begum 45 Isma Parveen 46 Sheikh M Roman Pervaiz 47 Saleem Akhtar 48 Samreen Ahmed 49 Muhammad Arshad Bhatti 50 Mahwish Madad Ali 51 Mahwish Madad Ali 52 Mahwish Madad Ali 53 Khalid Ali 54 Ghulam Murtaza 55 Hero 56 Muhammad Ibrahim 57 Mohammad Sajjad Khan 58 Waseem Ishaq 59 Adeel Ahmed Siddiqui 60 Noor Jahan 61 Ali Raza 62 Sarfaraz Tunio 63 Majed Khan 64 Tanveer Kosar 65 Ilyas Ahmed 66 Mazhar Ali 67 Mahwish Kanwal 68 Abdul Hai 69 Muneer Ahmed Shaikh 70 Shehzad Gulzar 71 Adnan Ahmed 72 Muhammad Arshad 73 Muhammad Shoukat 74 Muhammad Arif 75 Bashir Ahmed Memon 76 Muhammad Bashir 77 Saeed Ahmed 78 Bakhtyar Ahmed DETAILS OF UNCLAIMED INSURANCE BENEFITS AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 S.NO NAME 79 Nasreen Khurshid 80 Rahim Baig 81 Muhammad Ijaz 82 Sarwar Hussain 83 Muhammad Zafar 84 Saeed Ullah Khan 85 S.Wajid Hussain 86 Ch. -

Pakistan's Institutions

Pakistan’s Institutions: Pakistan’s Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Work They But How Can Matter, They Know We Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman and Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain Pakistan’s Institutions: We Know They Matter, But How Can They Work Better? Essays by Madiha Afzal Ishrat Husain Waris Husain Adnan Q. Khan, Asim I. Khwaja, and Tiffany M. Simon Michael Kugelman Mehmood Mandviwalla Ahmed Bilal Mehboob Umar Saif Edited by Michael Kugelman Ishrat Husain ©2018 The Wilson Center www.wilsoncenter.org This publication marks a collaborative effort between the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars’ Asia Program and the Fellowship Fund for Pakistan. www.wilsoncenter.org/program/asia-program fffp.org.pk Asia Program Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20004-3027 Cover: Parliament House Islamic Republic of Pakistan, © danishkhan, iStock THE WILSON CENTER, chartered by Congress as the official memorial to President Woodrow Wilson, is the nation’s key nonpartisan policy forum for tackling global issues through independent research and open dialogue to inform actionable ideas for Congress, the Administration, and the broader policy community. Conclusions or opinions expressed in Center publications and programs are those of the authors and speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Center staff, fellows, trustees, advisory groups, or any individuals or organizations that provide financial support to the Center. -

PM Pledges to Protect, Promote Businesses

10th December, 2018 PM pledges to protect, promote businesses Prime Minister Imran Khan on Sunday took into confidence the business community vowing to unveil a proper economic reform agenda to steer the country out of the current economic crisis. Also, the PM assured that his government was making all-out efforts to promote and protect business and investment in the country. During his day-long official visit to Karachi, the PM met with delegations of various trade associations, industrialists, provincial government officials, Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) representatives, Karachi Chambers of Commerce and Industry (KCCI), Overseas Investors Chamber of Commerce and Industry (OICCI) officials political party leaders etc and assured them to protect and promote the overall business environment in the country. In an interactive session with the managing committee members of Overseas Investors Chamber of Commerce and Industry (OICCI) at the Governor''s House the PM promised full support to foreign investors in addressing their issues and also shared salient points of the government''s economic recovery strategy. "We are working on a clear path for recovery and that the benefit of the revised economic strategy will be visible during the next six to nine months" Imran said. The Prime Minister promised to unveil in the coming weeks a proper economic reform agenda showing a clear road map for taking the country out of the current economic crisis. In a meeting with a delegation of the office bearers and brokers of Pakistan Stock Market Exchange headed by PSX''s Chairman Suleman Mehdi, the Prime Minister said his purpose of visit was to seek suggestions from traders and industrialists for the betterment of the national economy. -

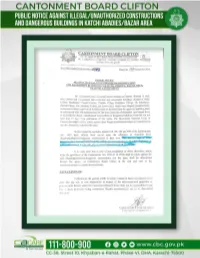

Public Notice Against Illegal / Unauthorized Constructions

CANTONMENT BOARD CLIFTON CC-38, Street 10, Kh-e-Rahat, Phase-VI, DHA, Karachi-75500 Ph. # 35847831-2, 35348774-5, 35850403, 35348784, Fax 5847835 Website: www.cbc.gov.pk _____________________________________ No. CBC/Lands/Publication/012/ Dated the 16 December 2020. PUBLIC NOTICE AGAINST ILLEGAL/UNAUTHORIZED CONSTRUCTION AND DANGEROUS BUILDINGS IN KATCHI ABADIES/BAZAR AREA CLIFTON CANTONMENT All concerned/owners/occupants/lessees/tenants are hereby directed in their own interest and convenience that residential and commercial buildings situated at Delhi Colony, Madniabad, Punjab Colony, Chandio Village, Bukhshan Village, Ch. Khaliq-uz-Zaman Colony, Pak Jamhoria Colony and Lower Gizri, which were illegally/unauthorizedly constructed without approval of building plans or deviated from the approved building plans or constructed with sub- standard material and may cause loss of properties and human lives, to demolish the illegal, unauthorized constructions or dangerous buildings forthwith but not later than 15 days from publication of this notice. The Honourable Supreme Court of Pakistan has taken serious notice against these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions and also directed to demolish the same. In this regard the requisites notices U/S 126, 185 and 256 of the Cantonments Act, 1924 have already been served upon the offenders to demolish these illegal/unauthorized/dangerous constructions at their own. The details of such properties are as under:- DEHLI COLONY NO.01 S. Property Name of present owner Violation/ status of Name of original Lessee No. No. as per record of CBC illegal construction 1 A-01/01 Mr. Noor Bat Khan Mrs. Abida Noor Ground + 7th Floor 2 A-01/02 Mr. -

Dr. Ishrat Hussain, Chairman IBA Centre of Excellence in Islamic Finance Education, Dr

Governor : Mr. Tariq Bajwa Title : Islamic Banking & Finance Awareness Drive - 2017 Date : August 03, 2017 Event : Opening Ceremony at Mega Event Islamic Banking & Finance Awareness Drive - 2017 Venue : Movenpick Hotel, Karachi Dr. Ishrat Hussain, Chairman IBA Centre of Excellence in Islamic Finance Education, Dr. Imran Usmani, Shariah Scholar, Mr. Irfan Siddiqui, Chairman Steering Committee on Islamic Finance Media Campaign, members of the Dunya Media Group, Presidents/CEOs of Banks and Financial Institutions, Distinguished Guests, Ladies & Gentlemen; Assalam-o-alaikum I am pleased to be here today at the opening ceremony of the mega event of Islamic Banking & Finance Awareness Drive-2017 by Dunya Media Group which was aimed at creating awareness and removing misconceptions about Islamic banking and finance in the country. Dunya Media Group deserves appreciation on successful completion of this awareness raising venture. I am hopeful that results of this campaign will be long lasting due to effective collaboration among various stakeholders and arranging multiple programs for public and targeted groups like students and business communities all across the country. Ladies & Gentlemen; Growth of Islamic banking industry particularly over the last decade is reflective of increasing acceptability of its merits; the total global size of the Islamic financial assets by end 2016 has reached to US $ 2.29 trillion and is expected to go beyond US $3 trillion by 20201. However, practitioners of Islamic finance cannot be complacent with this growth especially in the backdrop of changing global infrastructure for the financial sector. Today there is more than ever a compelling environment for Islamic finance industry to capitalise on its inherent strengths like asset backed nature of financial 1 Global Islamic Finance Report 2017 Page 1 of 4 transactions, being devoid of interest and prohibition against gambling, uncertainty and speculation to move away from the traditional business models and explore new opportunities. -

List of Category -I Members Registered in Membership Drive-Ii

LIST OF CATEGORY -I MEMBERS REGISTERED IN MEMBERSHIP DRIVE-II MEMBERSHIP CGN QUOTA CATEGORY NAME DOB BPS CNIC DESIGNATION PARENT OFFICE DATE MR. DAUD AHMAD OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT COMPANY 36772 AUTONOMOUS I 25-May-15 BUTT 01-Apr-56 20 3520279770503 MANAGER LIMITD MR. MUHAMMAD 38295 AUTONOMOUS I 26-Feb-16 SAGHIR 01-Apr-56 20 6110156993503 MANAGER SOP OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT CO LTD MR. MALIK 30647 AUTONOMOUS I 22-Jan-16 MUHAMMAD RAEES 01-Apr-57 20 3740518930267 DEPUTY CHIEF MANAGER DESTO DY CHEIF ENGINEER CO- PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 7543 AUTONOMOUS I 17-Apr-15 MR. SHAUKAT ALI 01-Apr-57 20 6110119081647 ORDINATOR COMMISSION 37349 AUTONOMOUS I 29-Jan-16 MR. ZAFAR IQBAL 01-Apr-58 20 3520222355873 ADD DIREC GENERAL WAPDA MR. MUHAMMA JAVED PAKISTAN BORDCASTING CORPORATION 88713 AUTONOMOUS I 14-Apr-17 KHAN JADOON 01-Apr-59 20 611011917875 CONTRALLER NCAC ISLAMABAD MR. SAIF UR REHMAN 3032 AUTONOMOUS I 07-Jul-15 KHAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110170172167 DIRECTOR GENRAL OVERS PAKISTAN FOUNDATION MR. MUHAMMAD 83637 AUTONOMOUS I 13-May-16 MASOOD UL HASAN 01-Apr-59 20 6110163877113 CHIEF SCIENTIST PROFESSOR PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISION 60681 AUTONOMOUS I 08-Jun-15 MR. LIAQAT ALI DOLLA 01-Apr-59 20 3520225951143 ADDITIONAL REGISTRAR SECURITY EXCHENGE COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD CHIEF ENGINEER / PAKISTAN ATOMIC ENERGY 41706 AUTONOMOUS I 01-Feb-16 LATIF 01-Apr-59 21 6110120193443 DERECTOR TRAINING COMMISSION MR. MUHAMMAD 43584 AUTONOMOUS I 16-Jun-15 JAVED 01-Apr-59 20 3820112585605 DEPUTY CHIEF ENGINEER PAEC WASO MR. SAGHIR UL 36453 AUTONOMOUS I 23-May-15 HASSAN KHAN 01-Apr-59 21 3520227479165 SENOR GENERAL MANAGER M/O PETROLEUM ISLAMABAD MR. -

China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

U A Z T m B PEACEWA RKS u E JI Bulunkouxiang Dushanbe[ K [ D K IS ar IS TA TURKMENISTAN ya T N A N Tashkurgan CHINA Khunjerab - - ( ) Ind Gilgit us Sazin R. Raikot aikot l Kabul 1 tro Mansehra 972 Line of Con Herat PeshawarPeshawar Haripur Havelian ( ) Burhan IslamabadIslamabad Rawalpindi AFGHANISTAN ( Gujrat ) Dera Ismail Khan Lahore Kandahar Faisalabad Zhob Qila Saifullah Quetta Multan Dera Ghazi INDIA Khan PAKISTAN . Bahawalpur New Delhi s R du Dera In Surab Allahyar Basima Shahadadkot Shikarpur Existing highway IRAN Nag Rango Khuzdar THESukkur CHINA-PAKISTANOngoing highway project Priority highway project Panjgur ECONOMIC CORRIDORShort-term project Medium and long-term project BARRIERS ANDOther highway IMPACT Hyderabad Gwadar Sonmiani International boundary Bay . R Karachi s Provincial boundary u d n Arif Rafiq I e nal status of Jammu and Kashmir has not been agreed upon Arabian by India and Pakistan. Boundaries Sea and names shown on this map do 0 150 Miles not imply ocial endorsement or 0 200 Kilometers acceptance on the part of the United States Institute of Peace. , ABOUT THE REPORT This report clarifies what the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor actually is, identifies potential barriers to its implementation, and assesses its likely economic, socio- political, and strategic implications. Based on interviews with federal and provincial government officials in Pakistan, subject-matter experts, a diverse spectrum of civil society activists, politicians, and business community leaders, the report is supported by the Asia Center at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). ABOUT THE AUTHOR Arif Rafiq is president of Vizier Consulting, LLC, a political risk analysis company specializing in the Middle East and South Asia. -

Sustainable Macro-Economic Growth Panelists’ Profile

Sustainable Macro-Economic Growth Panelists’ Profile Dr. Ishrat Husain was most recently Public Policy Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center, Washington D.C. He served as Dean & Director of Institute of Business Administration, Karachi from 2008 to 2016. Before that he was the Chairman, National Commission for Government Reforms from 2006 to 2008 with the status of Federal Minister reporting directly to the President and Prime Minister of Pakistan. He was appointed the Governor of Pakistan’s Central Bank in December 1999. During the next six years, he implemented a major program of restructuring of the Central Bank and steered the reforms of the banking sector. He spent two decades at the World Bank from 1979 to 1999 in various capacities including Director, Chief Economist, Division Chief and Resident Representative. He is a recipient of many prestigious international and national awards including Nishan e Dr. Ishrat Hussain Imtiaz, the highest civilian award conferred by the President of Panel Chair Pakistan in 2016 in recognition of his meritorious public service. Former Governor State Bank of Pakistan He has authored 18 books and monographs. two dozen refereed journal articles and 27 chapters in books. He is regularly invited as a speaker to international and national conferences and seminars. A business graduate, who majored in finance, Mr. Tarin started his career with Citibank Pakistan in 1975, and worked there for almost twenty-two years. In 1985, he was appointed Country Manager UAE and Oman and Regional Manager for Citibank’s Consumer Business in Gulf and Pakistan. In 1991, Mr. Tarin was appointed as the Country Manager, Citibank Pakistan. -

Bhutto a Political Biography.Pdf

Bhutto a Political Biography By: Salmaan Taseer Reproduced By: Sani Hussain Panhwar Member Sindh Council, PPP Bhutto a Political Biography; Copyright © www.bhutto.org 1 CONTENTS Preface .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 1 The Bhuttos of Larkana .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 2 Salad Days .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 18 3 Rake’s Progress .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 28 4 In the Field Marshal’s Service .. .. .. .. .. 35 5 New Directions .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 45 6 War and Peace 1965-6 .. .. .. .. .. .. 54 7 Parting of the Ways .. .. .. .. .. .. 69 8 Reaching for Power .. .. .. .. .. .. 77 9 To the Polls .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 102 10 The Great Tragedy .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 114 11 Reins of Power .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 125 12 Simla .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 134 13 Consolidation .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 147 14 Decline and Fall .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 163 15 The Trial .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 176 16 The Bhutto Conundrum .. .. .. .. .. 194 Select Bibliography .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 206 Bhutto a Political Biography; Copyright © www.bhutto.org 2 PREFACE Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was a political phenomenon. In a country where the majority of politicians have been indistinguishable, grey and quick to compromise, he stalked among them as a Titan. He has been called ‘blackmailer’, ‘opportunist’, ‘Bhutto Khan’ (an undisguised comparison with Pakistan’s military dictators Ayub Khan and Yahya Khan) and ‘His Imperial Majesty the Shahinshah of Pakistan’ by his enemies. Time magazine referred to him as a ‘whiz kid’ on his coming to power in 1971. His supporters called him Takhare Asia’ (The Pride of Asia) and Anthony Howard, writing of him in the New Statesman, London, said ‘arguably the most intelligent and plausibly the best read of the world’s rulers’. Peter Gill wrote of him in the Daily Telegraph, London: ‘At 47, he has become one of the third world’s most accomplished rulers.’ And then later, after a change of heart and Bhutto’s fall from power, he described him as ‘one of nature’s bounders’.