The Fiddle in a Tune: John Doherty and the Donegal Fiddle Tradition Driving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol 3

Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol 3 David H. Lyth July 2016 2 This is the third volume of a series of transcriptions of Irish traditional fiddle playing. The others are `Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol I' and `Bowing Styles in Irish Fiddle Playing Vol 2'. Volume 1 contains reels and hornpipes recorded by Michael Coleman, James Morrison and Paddy Killoran in the 1920's and 30's. Volume 2 contains several types of tune, recorded by players from Clare, Limerick and Kerry in the 1950's and 60's. Volumes I and II were both published by Comhaltas Ceoltoiri Eirann. This third volume returns to the players in Volume 1, with more tune types. In all three volumes, the transcriptions give the bowing used by the per- former. I have determined the bowing by slowing down the recording to the point where the gaps caused by the changes in bow direction can be clearly heard. On the few occasions when a gap separates two passages with the bow in the same direction, I have usually been able to find that out by demanding consistency; if a passage is repeated with the same gaps between notes, I assume that the directions of the bow are also repeated. That approach gives a reliable result for the tunes in these volumes. (For some other tunes it doesn't, and I have not included them.) The ornaments are also given, using the standard notation which is explained in Volumes 1 and 2. The tunes come with metronome settings, corresponding to the speed of the performance that I have. -

Traditional Irish Music Presentation

Traditional Irish Music Topics Covered: 1. Traditional Irish Music Instruments 2 Traditional Irish tunes 3. Music notation & Theory Related to Traditional Irish Music Trad Irish Instruments ● Fiddle ● Bodhrán ● Irish Flute ● Button Accordian ● Tin/Penny Whistle ● Guitar ● Uilleann Pipes ● Mandolin ● Harp ● Bouzouki Fiddle ● A fiddle is the same as a violin. For Irish music, it is tuned the same, low to high string: G, D, A, E. ● The medieval fiddle originated in Europe in ● The term “fiddle” is used the 10th century, which when referring to was relatively square traditional or folk music. shaped and held in the ● The fiddle is one of the arms. primarily used instruments for traditional Irish music and has been used for over 200 years in Ireland. Fiddle (cont.) ● The violin in its current form was first created in the early 16th century (early 1500s) in Northern Italy. ● When fiddlers play traditional Irish music, they ornament the music with slides, cuts (upper grace note), taps (lower grace note), rolls, drones (also known as a double stop), accents, staccato and sometimes trills. ● Irish fiddlers tend to make little use of vibrato, except for slow airs and waltzes, which is also used sparingly. Irish Flute ● Flutes have been played in Ireland for over a thousand years. ● There are two types of flutes: Irish flute and classical flute. ● Irish flute is typically used ● This flute originated when playing Irish music. in England by flautist ● Irish flutes are made of wood Charles Nicholson and have a conical bore, for concert players, giving it an airy tone that is but was adapted by softer than classical flute and Irish flautists as tin whistle. -

Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 3-1995 Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music Matthew S. Emmick Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Emmick, Matthew S., "Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music" (1995). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 21. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/21 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Matthew S. Emmick Applicant (Name as It Is to appear on dtplomo) Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle M'-Isic Thesis title _ May, 1995 lnter'lded date of commencemenf _ Read and approved by: ' -4~, <~ /~.~~ Thesis adviser(s)/ /,J _ 3-,;13- [.> Date / / - ( /'--/----- --",,-..- Commltte~ ;'h~"'h=j.R C~.16b Honors t-,\- t'- ~/ Flrst~ ~ Date Second Reader Date Accepied and certified: JU).adr/tJ, _ 2111c<vt) Director DiJe For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Magna Cum Laude Departmental Honors in Music and High Honors in Spanish Scottish and Irish Elements of Appalachian Fiddle Music A Thesis Presented to the Departmt!nt of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Matthew S. Emmick March, 24, 1995 -l _ -- -"-".,---. -

Extension Activity

Extension Activity - How the Banjo Became White Rhiannon Giddens is a multi-instrumentalist, singer, and found- ing member of the old-time music group Carolina Chocolate Drops. In 2017 she was awarded the Macarthur “Genius” Grant. Below are excerpts from a keynote address she gave at the 2017 International Bluegrass Music Association Conference, where she discusses the erasure of African Americans in the history of bluegrass, a genre that predominantly features the banjo. So more and more of late, the question has been asked: how do we get more diversity in bluegrass? Which of course, behind the hand, is really, why is bluegrass so white??? But the answer doesn’t lie in right now. Before we can look to the future, we need to understand the past. To understand how the banjo, which was once the ultimate symbol of African American musical expression, has done a 180 in popular understanding and become the emblem of the mythical white mountaineer—even now, in the age of Mumford and Sons, and Béla Fleck in Africa, and Taj Mahal’s “Colored Aristocracy,” the average person on the street sees a banjo and still thinks Deliverance, or The Beverly Hillbillies. In order to understand the history of the banjo and the history of bluegrass music, we need to move beyond the narratives we’ve inherited, beyond generalizations that bluegrass is mostly derived from a Scots-Irish tradition, with “influences” from Africa. It is actually a complex creole music that comes from multiple cultures, African and European and Native; the full truth that is so much more interesting, and American. -

Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin's Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowsk

Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin’s Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowski BMUS, University of Victoria, 2009 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the School of Music Monika Zaborowski, 2013 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Gestural Patterns in Kujaw Folk Performing Traditions: Implications for the Performer of Chopin’s Mazurkas by Monika Zaborowski BMUS, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Susan Lewis-Hammond, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Bruce Vogt, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Michelle Fillion, (School of Music) Departmental Member iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Susan Lewis-Hammond, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Bruce Vogt, (School of Music) Co-Supervisor Michelle Fillion, (School of Music) Departmental Member One of the major problems faced by performers of Chopin’s mazurkas is recapturing the elements that Chopin drew from Polish folk music. Although scholars from around 1900 exaggerated Chopin’s quotation of Polish folk tunes in their mixed agendas that related ‘Polishness’ to Chopin, many of the rudimentary and more complex elements of Polish folk music are present in his compositions. These elements affect such issues as rhythm and meter, tempo and tempo fluctuation, repetitive motives, undulating melodies, function of I and V harmonies. During his vacations in Szafarnia in the Kujawy region of Central Poland in his late teens, Chopin absorbed aspects of Kujaw performing traditions which served as impulses for his compositions. -

Suggested Repertoire

THE LEINSTER SCHOOL OF RATE YOUR ABILITY REPERTOIRE LIST MUSIC & DRAMA Level 1 Repertoire List Bog Down in the Valley Garryowen Polka Level 2 Repertoire List Maggie in the Woods Planxty Fanny Power Level 3 Repertoire List Jigs Learn to Play Irish Trad Fiddle The Kesh Jig (Tom Morley) The Hag’s Purse Blarney Pilgrim The Merry Blacksmith The Swallowtail Jig Tobin’s Favourite Double Jigs: (two, and three part jigs) The Hag at the Churn I Buried My Wife and Danced on her Grave The Carraroe Jig The Bride’s Favourite Saddle the Pony Rambling Pitchfork The Geese in the Bog (Key of C or D) The Lilting Banshee The Mist Covered Meadow (Junior Crehan Tune) Strike the Gay Harp Trip it Upstairs Slip Jigs: (two, and three part jigs) The Butterfly Éilish Kelly’s Delight Drops of Brandy The Foxhunter’s Deirdre’s Fancy Fig for a Kiss The Snowy Path (Altan) Drops of Spring Water Hornpipes Learn to Play Irish Trad Fiddle Napoleon Crossing the Alps (Tom Morley) The Harvest Home Murphys Hornpipes: (two part tunes) The Boys of Bluehill The Homeruler The Pride of Petravore Cornin’s The Galway Hornpipe Off to Chicago The Harvest Home Slides Slides (Two and three Parts) The Brosna Slides 1&2 Dan O’Keefes The Kerry Slide Merrily Kiss the Quaker Reels Learn to Play Irish Trad Fiddle The Raven’s Wing (Tom Morley) The Maid Behind the Bar Miss Monaghan The Silver Spear The Abbey Reel Castle Kelly Reels: (two part reels) The Crooked Rd to Dublin The Earl’s Chair The Silver Spear The Merry Blacksmith The Morning Star Martin Wynne’s No 1 Paddy Fahy’s No 1 Fr. -

Slate Mountain Ramblers

The Slate Mountain Ramblers The Slate Mountain Ramblers is a family old-time band from Mt. Airy, NC. They formerly lived in Ararat, VA, a small community at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains. For many years, Richard Bowman, his wife, Barbara, and their daughter Marsha, have spent weekends playing music. Richard plays fiddle, Barbara the bass and Marsha plays claw-hammer banjo. The band has a winning tradition by winning and placing at fiddler’s conventions they have attended throughout the years. Richard, on fiddle, and Marsha, on claw-hammer banjo, have received many individual awards. The Slate Mountain Ramblers play for shows, dances, family and community gatherings, benefits and compete at fiddler’s conventions throughout the year. They have played internationally at the Austrian Alps Performing Arts Festival and in Gainsborough, England for the Friends of American Old Time Music and Dance Festival. They also lead fiddle, banjo, bass and dance workshops. Richard Bowman is a champion fiddler, winning old-time fiddle competitions at many fiddlers conventions including Galax, Mt. Airy and Fiddler’s Grove. He has been playing the fiddle for about 45 years, the last 35 plus as leader of the Slate Mountain Ramblers. Learning from local old-time fiddlers, Richard’s long-bow style is easily recognizable. At fiddler’s conventions, he can be found with fellow musicians in a jam session. Other weekends finds Richard and the band playing for square dances where everyone enjoys flat footing or two-stepping to a pile of fiddle tunes. Marsha Bowman Todd is a hard driving clawhammer banjo player. -

Microtiming Analysis in Traditional Shetland Fiddle Music

MICROTIMING ANALYSIS IN TRADITIONAL SHETLAND FIDDLE MUSIC Estefanía Cano Scott Beveridge Fraunhofer IDMT Songquito [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT This work aims to characterize microtiming variations in traditional Shetland fiddle music. These microtiming vari- ations dictate the rhythmic flow of a performed melody, Unst and contribute, among other things, to the suitability of Scotland this music as an accompaniment to dancing. In the con- text of Shetland fiddle music, these microtiming variations are often referred to as lilt. Using a corpus of 27 tradi- Yell Fetlar tional fiddle tunes from the Shetland Isles, we examine inter-beat timing deviations, as well as inter-onset timing deviations of eighth note sequences. Results show a num- ber of distinct inter-beat and inter-onset rhythmic patterns Whalsay that may characterize lilt, as well as idiosyncratic patterns Mainland for each performer. This paper presents a first step towards the use of Music Information Retrieval (MIR) techniques for modelling lilt in traditional Scottish fiddle music, and highlights its implications in the field of ethnomusicology. 1. INTRODUCTION The Shetland Isles is an archipelago situated 100 miles north of the Scottish mainland (Figure 1). The distinctive music-culture of the Isles reflects a wide range of influ- Figure 1: The Shetland Isles ences from around the North-Atlantic, including mainland Scottish, Scandinavian, and North-American, in particular. The earliest evidence of a performance tradition on violin, notated consecutive eighth notes are not played with equal or fiddle, in the Shetland Isles dates from the eighteenth duration, often approximating a tied triplet notation with a century, but there is also evidence of a pre-violin string- 2:1 ratio [4]. -

2Ltuabus °E . .J2rl~E Com'qec1cions·

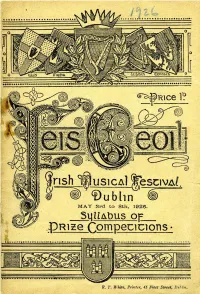

[ Q MAY .3rd to 8th, 1928. 2ltUAbus °E_. _ .J2Rl~e COm'QeC1CIOnS· 8.. 7', White, Printer, 4S Fleet Street, Dul·/:"u. " ( Notice to Competitors. OMPETITORS are requested to be careful that in the Feil Ceoil C Competitions, both Instrumental and Vocal, the specified edition is procured. Arrangements have been made by Mesers. Pigott &. Co., Ltd., THI~TIETH "3 Grafton Street, Dublin, to supply Candidates with the Test Piec~s in the correct editions at the lowe.t possible rates. F EIS C EO I L IRISH MUSICAL FESTIVAL. DUBLIN. MAY 3rd to 8th. 1926. SYLLABUS OF PRIZE COMPETITION S AND REPQRT OF MUSIC EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE. AND ALL THINOS MUSICAL. PIANOS ORGANS PLAYER - PIANOS GRAMOPHONES RECORDS VIOLINS Oreatest Facilities for Selection In Ireland. Service. of Expert Tuner. covera entire Country. Repair. by highly Skilled Craftsmen in the Firm'. Up-to-date Factory. DUBLIN : PUBLISHED BY THE FEIS CEOIL AS SOCIATION. 37 MOLESWORTH ST. 1926. GRAFTON ST. a SUFFOLK ST., DUBLIN. L ADd at CORK .. LIMUIC•• R. T. J-f/'lIite, Printer, 45 Fleet Street, Dtlblin, CONTENTS. ................................................ PAGE. 13 Adjudicators, List of. (1926) 6 It is earne.stiy ~equested that Competitions, Con~ltlons of . NOTICE. Constitution of Fels Ceoll 5 all Competitors should use Committees ... ... ... .. 4 Donors to Prize Fund (1925) ... .., 11 the correct and specified editions as stated Members of Association, List of (1925-26) 41 43 in Syllabus. •• •• :: .• Prize Winners, Calendar of .. Railway Travelling Facilities ... .. 11 Above are obtainable at Messrs. Report of Committee and Balance Sheets for 1925 34-40 McCullough's, 56 Dawson Street, Dublin. TEST PIECES AND PRIZES. -

Paradigmatic of Folk Music Tradition?

‘Fiddlers’ Tunebooks’ - Vernacular Instrumental Manuscript Sources 1860-c1880: Paradigmatic of Folk Music Tradition? By: Rebecca Emma Dellow A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music June 2018 2 Abstract Fiddlers’ Tunebooks are handwritten manuscript books preserving remnants of a largely amateur, monophonic, instrumental practice. These sources are vastly under- explored academically, reflecting a wider omission in scholarship of instrumental music participated in by ‘ordinary’ people in nineteenth-century England. The tunebooks generate interest amongst current folk music enthusiasts, and as such can be subject to a “burden of expectation”,1 in the belief that they represent folk music tradition. Yet both the concepts of tradition and folk music are problematic. By considering folk music from both an inherited perspective and a modern scholarly interpretation, this thesis examines the place of the tunebooks in notions of English folk music tradition. A historical musicological methodology is applied to three post-1850 case-study manuscripts drawing specifically on source studies, archival research and quantitative analysis. The study explores compilers’ demographic traits and examines content, establishing the existence of a heterogeneous repertoire copied from contemporary textual sources directly into the tunebooks. This raises important questions regarding the role played by publishers and the concept of continuous survival in notions of tradition. A significant finding reveals the interaction between aural and literate practices, having important implications in the inward and outward transmission and in wider historical application. The function of both the manuscripts and the musical practice is explored and the compilers’ acquisition of skill and sources is examined. -

Bellows & Bows: Historic Recordings of Traditional Fiddle & Accordion

Bellows & Bows: Historic Recordings of Traditional Fiddle & Accordion Music from across Canada Disc 1: Newfoundland and Labrador 1. I'se the B'y – Lillian Collins 2. Mrs. Belle's Cotillion – Mrs. Belle Fennelly 3. Young Man You Kissed Me Daughter – Gerald Quinton 4. O My Pretty Dear, Won’t You Come and Rub Me? – Dorman Ralph 5. French Reel – Ivan White 6. Golden Slippers – Tom Uvloriak 7. Inosiga – Tom and Sybilla Uvloriak Nova Scotia 8. La John Muise – Muriel Saulnier (née Muise) 9. La Bastringue – Stella Burridge 10. Marion Waltz / Caledonian Jig / Trip to Windsor – Johnny Mooring 11. Cape Blomindon Reel – Jack Greenough 12. Welcome to Your Feet Again / The Bonny Lass of Fisherrow/ The Bird’s Nest – Winston “Scotty” Fitzgerald 13. Calum Crùbach (Crippled Malcom) / Alex Currie’s Reel / Am Muileann Dubh (The Black Snuffmill) / Sandy Duff’s – Alex Currie 14. The Athole Highlanders Farewell to Loch Katrine / A Trip to Mabou Ridge – Theresa MacLellan Prince Edward Island 15. Princess Reel – Stephen Toole 16. Lad O’Beirne / Dublin Porter – Kenny Chaisson 17. Money Musk – Delphine Arsenault 18. La Marmotteuse – Eddy Arsenault New Brunswick 19. La tune à grand-père – Éloi Leblanc 20. La parenté – Yvon Babin 21. Loggieville Two-step – Matilda Murdoch 22. Zip Coon – Curtis Hicks 23. Sussex Avenue Fiddlers Two-step – The Sussex Avenue Fiddlers Quebec 24. La Ronfleuse – Arthur-Joseph Boulay 25. Reel de Sherbrooke – Les Montagnards Laurentiens 26. Le Brandy des Vaillaincourt – Louis “Pitou” Boudreault 27. Le Quadrille des Lanciers, 1e partie: “La Rencontre des Dames” – Jules Verret 28. La belle époque – Marcel Messervier 29. -

The Ngoni, the Banjo and the Atlantic Slave Trade

Mapping the Beat: A Geography through Music Curriculum ArtsBridge America Center for Learning through the Arts and Technology, UC Irvine Funded by National Geographic Education Foundation This curriculum unit for Mapping the Beat: A Geography through Music Curriculum was developed by Stephanie Feder (2007) at the University of California, Irvine with support from a grant from the National Geographic Education Foundation. The extended unit below was created by Dr. Timothy Keirn and the ArtsBridge America program at the California State University, Long Beach (2009). Other on-line resources, videos and lesson plans complied by the UC Irvine Center for Learning through the Arts and Technology are available at: http://www.clat.uci.edu/. LESSON: COUNTRY: AMERICA’S MUSIC (EARLY INFLUENCES AND INSTRUMENTS) Included in this document are: Part I: Lesson Part II: On-line resources for use with lesson Part III: Supporting Materials Part IV: Classroom Handouts, Worksheets and Visuals PART I: LESSON Mapping the Beat Fifth Grade Lesson: Country: America’s Music (Early Influences and Instruments) CONCEPT Early influences on modern American country music. How the migration of instruments of the Scots- Irish immigrants to Appalachia combined with those of the Atlantic slave trade influenced regional music. OBJECTIVE To visually recognize and describe instruments commonly associated with country music (namely the fiddle, guitar, and banjo), to recognize audio samples of music played by each instrument, and describe from where each instrument originated. STANDARDS ADDRESSED National Geography Standards Standard 4: The physical and human characteristics of places. How: Students identify and compare music and instruments of Scotland, Ireland, and Africa with that of American Appalachia during the 18th and 19th centuries.