The Making of the Heiltsuk Working Class: Methodism, Time Discipline, and Capitalist Subjectivities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia's Central Coast

A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia’s Central Coast REPORT · 2021 citation Atlas, W. I., K. Connors, L. Honka, J. Moody, C. N. Service, V. Brown, M .Reid, J. Slade, K. McGivney, R. Nelson, S. Hutchings, L. Greba, I. Douglas, R. Chapple, C. Whitney, H. Hammer, C. Willis, and S. Davies. (2021). A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia’s Central Coast. Vancouver, BC, Canada: Pacific Salmon Foundation. authors Will Atlas, Katrina Connors, Jason Slade Rich Chapple, Charlotte Whitney Leah Honka Wuikinuxv Fisheries Program Central Coast Indigenous Resource Alliance Salmon Watersheds Program, Wuikinuxv Village, BC Campbell River, BC Pacific Salmon Foundation Vancouver, BC Kate McGivney Haakon Hammer, Chris Willis North Coast Stock Assessment, Snootli Hatchery, Jason Moody Fisheries and Oceans Canada Fisheries and Oceans Canada Nuxalk Fisheries Program Bella Coola, BC Bella Coola, BC Bella Coola, BC Stan Hutchings, Ralph Nelson Shaun Davies Vernon Brown, Larry Greba, Salmon Charter Patrol Services, North Coast Stock Assessment, Christina Service Fisheries and Oceans Canada Fisheries and Oceans Canada Kitasoo / Xai’xais Stewardship Authority BC Prince Rupert, BC Klemtu, BC Ian Douglas Mike Reid Salmonid Enhancement Program, Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Fisheries and Oceans Canada Management Department Bella Coola, BC Bella Bella, BC published by Pacific Salmon Foundation 300 – 1682 West 7th Avenue Vancouver, BC, V6J 4S6, Canada www.salmonwatersheds.ca A Salmon Monitoring & Stewardship Framework for British Columbia’s Central Coast REPORT 2021 Acknowledgements We thank everyone who has been a part of this collaborative Front cover photograph effort to develop a salmon monitoring and stewardship and photograph on pages 4–5 framework for the Central Coast of British Columbia. -

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

We Are the Wuikinuxv Nation

WE ARE THE WUIKINUXV NATION WE ARE THE WUIKINUXV NATION A collaboration with the Wuikinuxv Nation. Written and produced by Pam Brown, MOA Curator, Pacific Northwest, 2011. 1 We Are The Wuikinuxv Nation UBC Museum of Anthropology Pacific Northwest sourcebook series Copyright © Wuikinuxv Nation UBC Museum of Anthropology, 2011 University of British Columbia 6393 N.W. Marine Drive Vancouver, B.C. V6T 1Z2 www.moa.ubc.ca All Rights Reserved A collaboration with the Wuikinuxv Nation, 2011. Written and produced by Pam Brown, Curator, Pacific Northwest, Designed by Vanessa Kroeker Front cover photographs, clockwise from top left: The House of Nuakawa, Big House opening, 2006. Photo: George Johnson. Percy Walkus, Wuikinuxv Elder, traditional fisheries scientist and innovator. Photo: Ted Walkus. Hereditary Chief Jack Johnson. Photo: Harry Hawthorn fonds, Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology. Wuikinuxv woman preparing salmon. Photo: C. MacKay, 1952, #2005.001.162, Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology. Stringing eulachons. (Young boy at right has been identified as Norman Johnson.) Photo: C. MacKay, 1952, #2005.001.165, Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology. Back cover photograph: Set of four Hàmac! a masks, collection of Peter Chamberlain and Lila Walkus. Photo: C. MacKay, 1952, #2005.001.166, Archives, UBC Museum of Anthropology. MOA programs are supported by visitors, volunteer associates, members, and donors; Canada Foundation for Innovation; Canada Council for the Arts; Department of Canadian Heritage Young Canada Works; BC Arts Council; Province of British Columbia; Aboriginal Career Community Employment Services Society; The Audain Foundation for the Visual Arts; Michael O’Brian Family Foundation; Vancouver Foundation; Consulat General de Vancouver; and the TD Bank Financial Group. -

Heiltsuk Nation Presentation

Heiltsuk Nation Presentation Marilyn Slett- HTC Chief Councillor Carrie Humchitt- GRS Kelly Brown- HIRMD Director June 8, 2015 Heiltsuk Land Use Our Vision u Since time immemorial, we the Heiltsuk people have managed all of our territory with respect and reverence for the life it sustains, using knowledge of marine and land resources passed down for generations. We have maintained a healthy and functioning environment while meeting our social and economic needs over hundreds of generations. Heiltsuk Land Use Our Vision u Our vision for the area remains unchanged. We will continue to balance our needs while sustaining the lands and resources that support us. We will continue to manage all Heiltsuk seas, lands and resources according to customary laws, traditional knowledge and nuyem (oral tradition) handed down by our ancestors, with consideration of the most current available scientific information” HLUP Executive Summary- Objectives u Introduction- Chief Marilyn Slett u Heiltsuk Herring/Heiltsuk Strong- Carrie Humchitt u Planning for Resilience- Kelly Brown What does Herring mean to Heiltsuk? u Our presentation will give a snapshot of what it means. It has many dimensions all deeply inter-connected to our relationship to the land and sea. u We are people of the sea - we live, gather and harvest from the sea, as my late uncle Cisco would say, "when the tide goes out....the table is set". u If we take care of the sea, the sea will take care of us. Heiltsuk Reflections u Herring has been the cornerstone of our Heiltsuk culture for thousands of years. u The annual herring harvest marks our traditional new year. -

Staying the Course, Staying Alive – Coastal First Nations Fundamental Truths: Biodiversity, Stewardship and Sustainability

Staying the Course, Staying Alive coastal first nations fundamental truths: biodiversity, stewardship and sustainability december 2009 Compiled by Frank Brown and Y. Kathy Brown Staying the Course, Staying Alive coastal first nations fundamental truths: biodiversity, stewardship and sustainability december 2009 Compiled by Frank Brown and Y. Kathy Brown Published by Biodiversity BC 2009 ISBN 978-0-9809745-5-3 This report is available both in printed form and online at www.biodiversitybc.org Suggested Citation: Brown, F. and Y.K. Brown (compilers). 2009. Staying the Course, Staying Alive – Coastal First Nations Fundamental Truths: Biodiversity, Stewardship and Sustainability. Biodiversity BC. Victoria, BC. 82 pp. Available at www.biodiversitybc.org cover photos: Ian McAllister (kelp beds); Frank Brown (Frank Brown); Ian McAllister (petroglyph); Ian McAllister (fishers); Candace Curr (canoe); Ian McAllister (kermode); Nancy Atleo (screened photo of canoers). title and copyright page photo: Shirl Hall section banner photos: Shirl Hall (pages iii, v, 1, 5, 11, 73); Nancy Atleo (page vii); Candace Curr (page xiii). design: Arifin Graham, Alaris Design printing: Bluefire Creative The stories and cultural practices among the Coastal First Nations are proprietary, as they belong to distinct families and tribes; therefore what is shared is done through direct family and tribal connections. T f able o Contents Foreword v Preface vii Acknowledgements xi Executive Summary xiii 1. Introduction: Why and How We Prepared This Book 1 2. The Origins of Coastal First Nations Truths 5 3. Fundamental Truths 11 Fundamental Truth 1: Creation 12 Fundamental Truth 2: Connection to Nature 22 Fundamental Truth 3: Respect 30 Fundamental Truth 4: Knowledge 36 Fundamental Truth 5: Stewardship 42 Fundamental Truth 6: Sharing 52 Fundamental Truth 7: Adapting to Change 66 4. -

Species at Risk Assessment—Pacific Rim National Park Reserve Of

Species at Risk Assessment—Pacific Rim National Park Reserve of Canada Prepared for Parks Canada Agency by Conan Webb 3rd May 2005 2 Contents 0.1 Acknowledgments . 10 1 Introduction 11 1.1 Background Information . 11 1.2 Objective . 16 1.3 Methods . 17 2 Species Reports 20 2.1 Sample Species Report . 21 2.2 Amhibia (Amphibians) . 23 2.2.1 Bufo boreas (Western toad) . 23 2.2.2 Rana aurora (Red-legged frog) . 29 2.3 Aves (Birds) . 37 2.3.1 Accipiter gentilis laingi (Queen Charlotte goshawk) . 37 2.3.2 Ardea herodias fannini (Pacific Great Blue heron) . 43 2.3.3 Asio flammeus (Short-eared owl) . 49 2.3.4 Brachyramphus marmoratus (Marbled murrelet) . 51 2.3.5 Columba fasciata (Band-tailed pigeon) . 59 2.3.6 Falco peregrinus (Peregrine falcon) . 61 2.3.7 Fratercula cirrhata (Tufted puffin) . 65 2.3.8 Glaucidium gnoma swarthi (Northern pygmy-owl, swarthi subspecies ) . 67 2.3.9 Megascops kennicottii kennicottii (Western screech-owl, kennicottii subspecies) . 69 2.3.10 Phalacrocorax penicillatus (Brandt’s cormorant) . 73 2.3.11 Ptychoramphus aleuticus (Cassin’s auklet) . 77 2.3.12 Synthliboramphus antiquus (Ancient murrelet) . 79 2.3.13 Uria aalge (Common murre) . 83 2.4 Bivalvia (Oysters; clams; scallops; mussels) . 87 2.4.1 Ostrea conchaphila (Olympia oyster) . 87 2.5 Gastropoda (Snails; slugs) . 91 2.5.1 Haliotis kamtschatkana (Northern abalone) . 91 2.5.2 Hemphillia dromedarius (Dromedary jumping-slug) . 95 2.6 Mammalia (Mammals) . 99 2.6.1 Cervus elaphus roosevelti (Roosevelt elk) . 99 2.6.2 Enhydra lutris (Sea otter) . -

5 Existing Environment

Pacific NorthWest LNG Environmental Impact Statement and Environmental Assessment Certificate Application Section 5: Existing Environment 5 EXISTING ENVIRONMENT The proposed Project will be primarily located on and around Lelu Island, which is on federal lands and waters under the jurisdiction of the Prince Rupert Port Authority (PRPA) and within the municipal boundaries of the District of Port Edward. Lelu Island is a small island (219 hectares) approximately 2.5 km southwest of the business centre of Port Edward and 12 km south of the business centre for the City of Prince Rupert (Figure 1-2). It has been identified as having long-term potential for a bulk terminal, shipyard and other marine activity in the Prince Rupert Port Authority’s (PRPA) 2020 Land Use Management Plan (PRPA 2010). The District of Port Edward’s 2013 official community plan reports that the island currently is only accessible by water and has the potential to connect to Port Edward by bridge crossing for road access off of Skeena Drive (DOPE 2013). 5.1 Atmospheric Environment and Climate 5.1.1 Climate The Prince Rupert area is within a thin coastal strip west of the windward slopes of the Coast Mountains. Weather conditions in the area are recorded at the Environment Canada weather station at the Prince Rupert Airport, 7 km west of Prince Rupert; and the Holland Rock weather station, 5 km northwest of Lelu Island. Generally, westerly winds carry moist, warm Pacific air streams up and over the Coast Mountains, depositing large amounts of precipitation (mainly as rain) over the Prince Rupert region. -

The Fur Trade Era, 1770S–1849

Great Bear Rainforest The Fur Trade Era, 1770s–1849 The Fur Trade Era, 1770s–1849 The lives of First Nations people were irrevocably changed from the time the first European visitors came to their shores. The arrival of Captain Cook heralded the era of the fur trade and the first wave of newcomers into the future British Columbia who came from two directions in search of lucrative pelts. First came the sailors by ship across the Pacific Ocean in pursuit of sea otter, then soon after came the fort builders who crossed the continent from the east by canoe. These traders initiated an intense period of interaction between First Nations and European newcomers, lasting from the 1780s to the formation of the colony of Vancouver Island in 1849, when the business of trade was the main concern of both parties. During this era, the newcomers depended on First Nations communities not only for furs, but also for services such as guiding, carrying mail, and most importantly, supplying much of the food they required for daily survival. First Nations communities incorporated the newcomers into the fabric of their lives, utilizing the new trade goods in ways which enhanced their societies, such as using iron to replace stone axes and guns to augment the bow and arrow. These enhancements, however, came at a terrible cost, for while the fur traders brought iron and guns, they also brought unknown diseases which resulted in massive depopulation of First Nations communities. European Expansion The northwest region of North America was one of the last areas of the globe to feel the advance of European colonialism. -

Mutiny on the Beaver 15 Mutiny on the Beaver: Law and Authority in the Fur Trade Navy, 1835-1840

Mutiny on the Beaver 15 Mutiny on the Beaver: Law and Authority in the Fur Trade Navy, 1835-1840 Hamar Foster* ... I decided on leaving them to be dealt with through the slow process of the law, as being in the end more severe than a summary infliction." L INTRODUCTION IT IS CONVENTIONAL TO SEEK THE HISTORICAL ROOTS of British Columbia labour in the colonial era, that is to say, beginning in 1849 or thereabouts. That was when Britain established Vancouver Island, its first colony on the North Pacific coast, and granted the Hudson's 1991 CanLIIDocs 164 Bay Company fee simple title on the condition that they bring out settlers.' It is a good place to begin, because the first batch of colonists were not primarily gentlemen farmers or officials but coal miners and agricultural labourers, and neither the Company nor Vancouver Island lived up to their expectations.' The miners were Scots, brought in to help the Hudson's Bay Company diversify and exploit new resources in the face of declining fur trade profits, but * Hamar Foster is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Victoria, teaching a variety of subjects, including legal history. He has published widely in the field of Canadian legal history, as well as in other areas of law. James Douglas, Reporting to the Governor and Committee on the "Mutiny of the Beaver Crew, 1838", Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Hudson's Bay Company Archives [hereinafter HBCA] B. 223/6/21. ' In what follows the Hudson's Bay Company ("IHC') will be referred to as "they," etc., rather than "it". -

Table 5-4. the North American Tribes Coded for Cannibalism by Volhard

Table 5-4. The North American tribes coded for cannibalism by Volhard and Sanday compared with all North American tribes, grouped by language and region See final page for sources and notes. Sherzer’s Language Groups (supplemented) Murdock’s World Cultures Volhard’s Cases of Cannibalism Region Language Language Language or Tribe or Region Code Sample Cluster or Tribe Case No. Family Group or Dialect Culture No. Language 1. Tribes with reports of cannibalism in Volhard, by region and language Language groups found mainly in the North and West Western Nadene Athapascan Northern Athapascan 798 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Chipewayan Northern ND7 Tschipewayan 799 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Slave Northern ND14 128 Subarctic Canada Western Nadene Athapascan Chipewayan Yellowknife Northern ND14 Subarctic Canada Northwest Salishan Coast Salish Bella Coola Bella Coola British NE6 132 Bilchula, Bilqula 795 Coast Columbia Northwest Penutian Tsimshian Tsimshian Tsimshian British NE15 Tsimschian 793 Coast Columbia Northwest Wakashan Wakashan Helltsuk Helltsuk British NE5 Heiltsuk 794 Coast Columbia Northwest Wakashan Wakashan Kwakiutl Kwakiutl British NE10 Kwakiutl* 792, 96, 97 Coast Columbia California Penutian Maidun Maidun Nisenan California NS15 Nishinam* 809, 810 California Yukian Yuklan Yuklan Wappo California NS24 Wappo 808 Language groups found mainly in the Plains Plains Sioux Dakota West Central Plains Sioux Dakota Assiniboin Assiniboin Prairie NF4 Dakota 805 Plains Sioux Dakota Gros Ventre Gros Ventre West Central NQ13 140 Plains Sioux Dakota Miniconju Miniconju West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Santee Santee West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Teton Teton West Central NQ11 Plains Sioux Dakota Yankton Yankton West Central NQ11 Sherzer’s Language Groups (supplemented) Murdock’s World Cultures Volhard’s Cases of Cannibalism Region Language Language Language or Tribe or Region Code Sample Cluster or Tribe Case No. -

1 the Phonology of Wakashan Languages Adam Werle University

1 The Phonology of Wakashan Languages Adam Werle University of Victoria, March 2010 Abstract This article offers an overview of the phonological typology and analysis of the Wakashan languages, namely Haisla, Heiltsukvla (Heiltsuk, Bella Bella), Oowekyala, Kwak’wala (Kwakiutl), Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka), Ditidaht (Nitinaht), and Makah. Like other languages of the Northwest Coast of North America, these have many consonants, including several laterals, front and back dorsals, few labials, contrastive glottalization and lip rounding, and a glottal stop with similar distribution to other consonants. Consonant-vowel sequences are characterized by large obstruent clusters, and no hiatus. Of theoretical interest at the segmental level are consonant mutations, positional neutralizations of laryngeal features, vowel-glide alternations, glottalized vowels and glottalized voiced plosives, and historical loss of nasal consonants. Also addressed here are aspects of these languages’ rich prosodic morphology, such as patterns of reduplication and templatic stem modifications, the distribution of Northern Wakashan schwa, alternations in Southern Wakashan vowel length and presence, and the syllabification of all-obstruent words. 1. Introduction The Wakashan language are spoken in what are now British Columbia, Canada, and Washington State, USA. The family comprises a northern branch—Haisla, Heiltsukvla, Oowekyala, and Kwa kwala—and̓ a southern branch—Nuu-chah-nulth, Ditidaht, and Makah— that diverge significantly from each other, but are internally very similar. They are endangered, being spoken natively by about 350 people, out of ethnic populations of about 23,000 whose main language is English. At the same time, most are undergoing active revitalization, with about 1,000 semi-speakers and learners ( First Peoples’ Language Map ). -

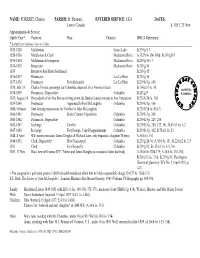

FORREST, Charles PARISH: St

NAME: FORREST, Charles PARISH: St. Edouard, ENTERED SERVICE: 1824 DATES: Lower Canada d. 1851, 23 Nov. Appointments & Service Outfit Year*: Position: Post: District: HBCA Reference: *An Outfit year ran from 1 June to 31 May 1825-1828 Middleman Island Lake B.239/g/5-7 1828-1830 Middleman & Clerk Mackenzie River A.32/29 fo.106-106d; B.239/g/8-9 1830-1834 Middleman & Interpreter Mackenzie River B.239/g/10-13 1834-1835 Interpreter Mackenzie River B.239/g/14 1835 Retired to Red River Settlement B.239/g/15 1836-1837 Postmaster Lac La Pluie B.239/g/16 1837-1838 Postmaster Fort Alexander Lac La Pluie B.239/k/3 p. 160 1838, July 24 Charles Forrest, passenger for Columbia, departed from Norway House B.154/a/31 fo. 9d ARCHIVES 1838-1839 Postmaster, Disposable+ Columbia B.223/g/5 WINNIPEG 1839, August 16 Proceeded to Fort Nez Perces to bring down the Snake Country returns to Fort Vancouver B.223/b/24 fo. 39d 1839-1840 Postmaster Appointed to Fort McLoughlin Columbia B.239/k/3 p. 186 1840, February Sent farming instructions for Cowlitz by John McLoughlin B.223/b/24 fo. 63d-71 1840-1841 Postmaster Snake Country Expedition Columbia B.239/k/3 p. 206 1841-1842 Postmaster, Disposable+ Columbia B.239/k/3 p. 229, 258 1842-1847 In charge Cowlitz Columbia B.239/k/3 p. 280, 332, 361; B.47/z/1 fo. 1-2 1847-1848 In charge Fort George, Cape Disappointment Columbia B.239/k/3 p.