Century Operas on Vocal Pedagogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Caffarelli

Caffarelli pt3 VOIX-DES-ARTS.COM, 21_09_2013 http://www.voix-des-arts.com/2013/09/cd-review-arias-for-caffarelli-franco.html 21 September 2013 CD REVIEW: ARIAS FOR CAFFARELLI (Franco Fagioli, countertenor; Naïve V 5333) PASQUALE CAFARO (circa 1716 – 1787) JOHANN ADOLF HASSE (1699 – 1783), LEONARDO LEO (1694 – 1744), GENNARO MANNA (1715 – 1779), GIOVANNI BATTISTA PERGOLESI (1710 – 1736), NICOLA ANTONIO PORPORA (1686 – 1768), DOMENICO SARRO (1679 – 1744), and LEONARDO VINCI (1690 – 1730): Arias for Caffarelli—Franco Fagioli, countertenor; Il Pomo d’Oro; Riccardo Minasi [Recorded at the Villa San Fermo, Convento dei Pavoniani, Lonigo, Vicenza, Italy, 25 August – 3 September 2012; Naïve V 5333; 1CD, 78:31; Available from Amazon, fnac, JPC, and all major music retailers] If contemporary accounts of his demeanor can be trusted, Gaetano Majorano—born in 1710 in Bitonto in the Puglia region of Italy and better known to history as Caffarelli—could have given the most arrogant among the opera singers of the 21st Century pointers on enhancing their self-appreciation. Unlike many of his 18th-Century rivals, Caffarelli enjoyed a certain level of privilege, his boyhood musical studies financed by the profits of two vineyards devoted to his tuition by his grandmother. Perhaps most remarkable, especially in comparison with other celebrated castrati who invented elaborate tales of childhood illnesses and unfortunate encounters with unfriendly animals to account for their ‘altered’ states, is the fact that, having been sufficiently impressed by the quality of his puerile voice or convinced thereof by the praise of his tutors, Caffarelli volunteered himself for castration. It is suggested that his most influential teacher, Porpora, with whom Farinelli also studied, was put off by Caffarelli’s arrogance but regarded him as the most talented of his pupils, reputedly having pronounced the castrato the greatest singer in Europe—a sentiment legitimately expressive of Porpora’s esteem for Caffarelli, perhaps, and surely a fine advertisement for his own services as composer and teacher. -

A Passion for Opera the DUCHESS and the GEORGIAN STAGE

A Passion for Opera THE DUCHESS AND THE GEORGIAN STAGE A Passion for Opera THE DUCHESS AND THE GEORGIAN STAGE PAUL BOUCHER JEANICE BROOKS KATRINA FAULDS CATHERINE GARRY WIEBKE THORMÄHLEN Published to accompany the exhibition A Passion for Opera: The Duchess and the Georgian Stage Boughton House, 6 July – 30 September 2019 http://www.boughtonhouse.co.uk https://sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/projects/passion-for-opera First published 2019 by The Buccleuch Living Heritage Trust The right of Paul Boucher, Jeanice Brooks, Katrina Faulds, Catherine Garry, and Wiebke Thormählen to be identified as the authors of the editorial material and as the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors. ISBN: 978-1-5272-4170-1 Designed by pmgd Printed by Martinshouse Design & Marketing Ltd Cover: Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Lady Elizabeth Montagu, Duchess of Buccleuch, 1767. Portrait commemorating the marriage of Elizabeth Montagu, daughter of George, Duke of Montagu, to Henry, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch. (Cat.10). © Buccleuch Collection. Backdrop: Augustus Pugin (1769-1832) and Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827), ‘Opera House (1800)’, in Rudolph Ackermann, Microcosm of London (London: Ackermann, [1808-1810]). © The British Library Board, C.194.b.305-307. Inside cover: William Capon (1757-1827), The first Opera House (King’s Theatre) in the Haymarket, 1789. -

Aaron Sherber Conductor

Aaron Sherber Conductor 2306 West Rogers Avenue Baltimore, Maryland 21209 [email protected] • 443.386.2033 Experience Third Millennium Ensemble Conductor 2007, 2019 Martha Graham Dance Company Music Director 1998–2017 The Juilliard School Guest Conductor 2015 Baltimore School for the Arts Guest Conductor 2013 Baltimore Concert Opera Conductor 2012, 2009 Boston Conservatory Guest Conductor 2005 University of California, Davis Artist in Residence 2004 Birmingham (UK) Royal Ballet Guest Conductor 2004 Opera Vivente Music Director 1998–2003 Baltimore, Maryland Howard County (MD) Ballet Guest Conductor 2001 Baltimore Opera Company Assistant Conductor 2000 Johns Hopkins Symphony Orchestra Guest Conductor 1999 Baltimore, Maryland Maryland Lyric Opera Conductor 1999 Young Victorian Theatre Company Assistant Conductor 1998–99 Baltimore, Maryland Orlando Opera Company Apprentice Conductor 1996 Washington (DC) Symphony Orchestra Assistant Conductor 1995 Summer Opera Theatre Company Assistant Conductor 1995 Washington, DC Peabody Conservatory Opera Department Staff Conductor 1992–94 Baltimore, Maryland Peabody Opera Workshop Conductor 1991–94 Branford Chamber Orchestra Music Director 1988–89 New Haven, Connecticut Education Peabody Conservatory of Music MM in conducting 1992 Study with Frederik Prausnitz Yale College BA in philosophy 1989 Study with Alasdair Neale Aaron Sherber Conductor 2306 West Rogers Avenue Baltimore, Maryland 21209 [email protected] • 443.386.2033 Biography Aaron Sherber was the music director and conductor of the Martha Graham Dance Company from 1998 to 2017 and led them in acclaimed performances at venues on three continents, including City Center and the Joyce Theater in New York, the Kennedy Center and the Library of Congress in Washington DC, Sadler’s Wells in London, and the National Center for the Performing Arts in Beijing. -

Metropolitan Opera 19-20 Season Press Release

Updated: November 12, 2019 New Productions of Porgy and Bess, Der Fliegende Holländer, and Wozzeck, and Met Premieres of Agrippina and Akhnaten Headline the Metropolitan Opera’s 2019–20 Season Yannick Nézet-Séguin, in his second season as Music Director, conducts the new William Kentridge production of Wozzeck, as well as two revivals, Met Orchestra concerts at Carnegie Hall, and a New Year’s Eve Puccini Gala starring Anna Netrebko Sunday matinee performances are offered for the first time From Roberto Alagna to Sonya Yoncheva, favorite Met singers return Debuting conductors are Karen Kamensek, Antonello Manacorda, and Vasily Petrenko; returning maestros include Valery Gergiev and Sir Simon Rattle New York, NY (February 20, 2019)—The Metropolitan Opera today announced its 2019–20 season, which opens on September 23 with a new production of the Gershwins’ classic American opera Porgy and Bess, last performed at the Met in 1990, starring Eric Owens and Angel Blue, directed by James Robinson and conducted by David Robertson. Philip Glass’s Akhnaten receives its Met premiere with Anthony Roth Costanzo as the title pharaoh and J’Nai Bridges as Nefertiti, in a celebrated staging by Phelim McDermott and conducted by Karen Kamensek in her Met debut. Acclaimed visual artist and stage director William Kentridge directs a new production of Berg’s Wozzeck, starring Peter Mattei and Elza van den Heever, and led by the Met’s Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin. In another Met premiere, Sir David McVicar stages the black comedy of Handel’s Agrippina, starring Joyce DiDonato as the conniving empress with Harry Bicket on the podium. -

The Inventory of the Deborah Voigt Collection #1700

The Inventory of the Deborah Voigt Collection #1700 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center Voigt, Deborah #1700 6/29/05 Preliminary Listing I. Subject Files. Box 1 A Chronological files; includes printed material, photographs, memorabilia, professional material, other items. 1. 1987-1988. [F. 1] a. Mar. 1987; newsletters of The Riverside Opera Association, Verdi=s AUn Ballo in Maschera@ (role of Amelia). b. Apr. 1987; program from Honolulu Symphony (DV on p. 23). c. Nov. 1987; program of recital at Thorne Hall. d. Jan. 1988; program of Schwabacher Debut Recitals and review clippings from the San Francisco Examiner and an unknown newspaper. e. Mar. 1988; programs re: DeMunt=s ALa Monnaie@ and R. Strauss=s AElektra@ (role of Fünfte Magd). f. Apr. 1988; magazine of The Minnesota Orchestra Showcase, program for R. Wagner=s ADas Rheingold@ (role of Wellgunde; DV on pp. 19, 21), and review clippings from the Star Tribune and the St. Paul Pioneer Press Dispatch. g. Sep. - Oct. 1988; programs re: Opera Company of Philadelphia and the International Voice Competition (finalist competition 3; DV on p. 18), and newspaper clippings. 2. 1989. [F. 2] a. DV=s itineraries. (i) For Jan. 4 - Feb. 9, TS. (ii) For the Johann Strauss Orchestra on Vienna, Jan. 5 - Jan. 30, TS, 7 p. b. Items re: California State, Fullerton recital. (i) Copy of Daily Star Progress clipping, 2/10/89. (ii) Compendium of California State, Fullerton, 2/13/89. (iii) Newspaper clipping, preview, n.d. (iv) Orange County Register preview, 2/25/89. (v) Recital flyer, 2/25/89. (vi) Recital program, program notes, 2/25/89. -

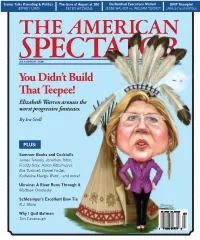

You Didn't Build That Teepee!

Trump Talks Parenting & Politics The Guns of August at 100 Do Botched Executions Matter? UKIP Triumphs! JEFFREY LORD PETER HITCHENS JESSE WALKER vs. WILLIAM TUCKER JAMES DELINGPOLE JULY/AUGUST 2014 A MONTHLY REVIEW EDITED BY R. EMMETT TYRRELL, JR. You Didn’t Build That Teepee! Elizabeth Warren arouses the worst progressive fantasies. By Ira Stoll PLUS: Summer Books and Cocktails James Taranto, Jonathan Tobin, Freddy Gray, Helen Rittelmeyer, Eve Tushnet, Daniel Foster, Katherine Mangu-Ward…and more! Ukraine: A River Runs Through It Matthew Omolesky Schlesinger’s Excellent Bow Tie R.J. Stove Why I Quit Batman Tim Cavanaugh 1 5 1 5 1 5 1 5 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 100 100 100 100 “ The best detector is not merely the one that can pick up radar from the farthest distance, although the Valentine One continues to score best.” — Autoweek Now V1 comes to a touchscreen near you. Introducing the Threat Picture You can see the arrows at work on your compatible iPhone® or AndroidTM device. Check it out… The app is free! Yo u can download V1connection, the app Where’s the radar? It’s in the Box. for free. Go to the app store on your device. When installed, the app automatically runs in Demo Mode. No need to link to V1. Analyze preloaded threat situations on three different screens: on the V1 screen, Arrow in the Box means a threat in the radar zone. on Picture, and on List. Then when you’re ready to put the Threat Picture on duty in your car, order the Bluetooth® communication module directly from us. -

Handel Arias

ALICE COOTE THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET HANDEL ARIAS HERCULES·ARIODANTE·ALCINA RADAMISTO·GIULIO CESARE IN EGITTO GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL A portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685–1749) 2 CONTENTS TRACK LISTING page 4 ENGLISH page 5 Sung texts and translation page 10 FRANÇAIS page 16 DEUTSCH Seite 20 3 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759) Radamisto HWV12a (1720) 1 Quando mai, spietata sorte Act 2 Scene 1 .................. [3'08] Alcina HWV34 (1735) 2 Mi lusinga il dolce affetto Act 2 Scene 3 .................... [7'45] 3 Verdi prati Act 2 Scene 12 ................................. [4'50] 4 Stà nell’Ircana Act 3 Scene 3 .............................. [6'00] Hercules HWV60 (1745) 5 There in myrtle shades reclined Act 1 Scene 2 ............. [3'55] 6 Cease, ruler of the day, to rise Act 2 Scene 6 ............... [5'35] 7 Where shall I fly? Act 3 Scene 3 ............................ [6'45] Giulio Cesare in Egitto HWV17 (1724) 8 Cara speme, questo core Act 1 Scene 8 .................... [5'55] Ariodante HWV33 (1735) 9 Con l’ali di costanza Act 1 Scene 8 ......................... [5'42] bl Scherza infida! Act 2 Scene 3 ............................. [11'41] bm Dopo notte Act 3 Scene 9 .................................. [7'15] ALICE COOTE mezzo-soprano THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET conductor 4 Radamisto Handel diplomatically dedicated to King George) is an ‘Since the introduction of Italian operas here our men are adaptation, probably by the Royal Academy’s cellist/house grown insensibly more and more effeminate, and whereas poet Nicola Francesco Haym, of Domenico Lalli’s L’amor they used to go from a good comedy warmed by the fire of tirannico, o Zenobia, based in turn on the play L’amour love and a good tragedy fired with the spirit of glory, they sit tyrannique by Georges de Scudéry. -

Oct Complete.Indd

courtesy of the Baltimore Opera Company New Repertoire Discoveries for Singers: An Interview with Michael Kaye by Maria Nockin Many young singers may id you ever wonder why that last which I established my edition of the Tales of Tales of Hoffmann you sang had all Hoffmann, I had to seek my own funding, but not yet be ready to do Dthose photocopied sheets added in? it’s very diffi cult to ask for a grant for yourself. Or why the version of “Butterfl y” you learned Fortunately, Gordon Getty, Frederick R. Giacomo Puccini’s operatic a few years ago isn’t the version you’re doing Koch, Paula Heil Fisher and the late Francis this year? Blame Michael Kaye and other Goelett (a great lover of contemporary music roles—but they can sing musicologists, who are diligently uncovering and French opera, who donated the funding authentic music faster than publishers can for many new productions of French works the great composer’s print it! Here’s some news teachers and at the Metropolitan Opera) were among recitalists can use. the generous private sponsors of my work. songs, and learn a great First recordings of previously unpublished MN: So you are one of the guilty parties music by important composers, and fi nancial deal about his style. responsible for making it impossible for advances from publishers, sometimes can singers to learn “the defi nitive Hoffmann!” Do help subsidize the preparation of the music you apply for grants so that you can work on for performance. fi nding lost music? There are also grants, endowments and MK: Normally that work is done under an fellowships that provide funding for this type umbrella of academia, but I had to fi nd other of research. -

Central Opera Service Bulletin • Vol

CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE COMMITTEE Founder MRS. AUGUST BELMONT Honorary National Chairman ROBERT L. B. TOBIN National Chairman ELIHU M. HYNDMAN National Co-Chairmen MRS. NORRIS DARRELL GEORGE HOWERTON Profntional Committee KURT HERBERT ADLER BORIS GOLDOVSKY San Francisco Opera Goldovsky Opera Theatre WILFRED C. BAIN DAVID LLOYD Indiana University Lake George Opera Festival GRANT BEGLARIAN LOTFI MANSOURI University of So. California Canadian Opera Company MORITZ BOMHARD GLADYS MATHEW Kentucky Opera Association Community Opera SARAH CALDWELL RUSSELL D. PATTERSON Opera Company of Boston Lyric Opera of Kansas City TITO CAPOBIANCO MRS. JOHN DEWITT PELTZ San Diego Opera Metropolitan Opera KENNETH CASWELL EDWARD PURRINGTON Memphis Opera Theatre Tulsa Opera ROBERT J. COLLINGE GLYNN ROSS Baltimore Opera Company Seattle Opera Association JOHN CROSBY JULIUS RUDEL Santa Fe Opera New York City Opera WALTER DUCLOUX MARK SCHUBART University of Texas Lincoln Center ROBERT GAY ROGER L. STEVENS Northwestern University John F. Kennedy Center DAVID GOCKLEY GIDEON WALDROP Houston Grand Opera The Juilliard School Central Opera Service Bulletin • Vol. 21, No. 4 • 1979/80 Editor, MARIA F. RICH Assistant Editor, JEANNE HANIFEE KEMP The COS Bulletin is published quarterly for its members by Central Opera Service. For membership information see back cover. Permission to quote is not necessary but kindly note source. Please send any news items suitable for mention in the COS Bulletin as well as performance information to The Editor, Central Opera Service Bulletin, Metropolitan Opera, Lincoln Center, New York, NY 10023. Copies this issue: $2.00 |$SN 0008-9508 NEW OPERAS AND PREMIERES Last season proved to be the most promising yet for new American NEW operas, their composers and librettists. -

Susan Rutherford: »Bel Canto« and Cultural Exchange

Susan Rutherford: »Bel canto« and cultural exchange. Italian vocal techniques in London 1790–1825 Schriftenreihe Analecta musicologica. Veröffentlichungen der Musikgeschichtlichen Abteilung des Deutschen Historischen Instituts in Rom Band 50 (2013) Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Rom Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat der Creative- Commons-Lizenz Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) unterliegt. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Den Text der Lizenz erreichen Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode »Bel canto« and cultural exchange Italian vocal techniques in London 1790–1825 Susan Rutherford But let us grant for a moment, that the polite arts are as much upon the decline in Italy as they are getting forward in England; still you cannot deny, gentlemen, that you have not yet a school which you can yet properly call your own. You must still admit, that you are obliged to go to Italy to be taught, as it has been the case with your present best artists. You must still submit yourselves to the direction of Italian masters, whether excellent or middling. Giuseppe -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXI, Number 3 Winter 2006 AMERICAN HANDEL SOCIETY- PRELIMINARY SCHEDULE (Paper titles and other details of program to be announced) Thursday, April 19, 2006 Check-in at Nassau Inn, Ten Palmer Square, Princeton, NJ (Check in time 3:00 PM) 6:00 PM Welcome Dinner Reception, Woolworth Center for Musical Studies Covent Garden before 1808, watercolor by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd. 8:00 PM Concert: “Rule Britannia”: Richardson Auditorium in Alexander Hall SOME OVERLOOKED REFERENCES TO HANDEL Friday, April 20, 2006 In his book North Country Life in the Eighteenth Morning: Century: The North-East 1700-1750 (London: Oxford University Press, 1952), the historian Edward Hughes 8:45-9:15 AM: Breakfast, Lobby, Taplin Auditorium, quoted from the correspondence of the Ellison family of Hebburn Hall and the Cotesworth family of Gateshead Fine Hall Park1. These two families were based in Newcastle and related through the marriage of Henry Ellison (1699-1775) 9:15-12:00 AM:Paper Session 1, Taplin Auditorium, to Hannah Cotesworth in 1729. The Ellisons were also Fine Hall related to the Liddell family of Ravenscroft Castle near Durham through the marriage of Henry’s father Robert 12:00-1:30 AM: Lunch Break (restaurant list will be Ellison (1665-1726) to Elizabeth Liddell (d. 1750). Music provided) played an important role in all of these families, and since a number of the sons were trained at the Middle Temple and 12:15-1:15: Board Meeting, American Handel Society, other members of the families – including Elizabeth Liddell Prospect House Ellison in her widowhood – lived in London for various lengths of time, there are occasional references to musical Afternoon and Evening: activities in the capital. -

Season Premiere of Tosca Glitters

2019–20 Season Repertory and Casting Casting as of November 12, 2019 *Met debut The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess By George Gershwin, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, and Ira Gershwin New Production Sep 23, 27, 30, Oct 5mat, 10, 13mat, 16, Jan 8, 11, 15, 18, 24, 28, Feb 1mat Conductor: David Robertson Bess: Angel Blue/Elizabeth Llewellyn* Clara: Golda Schultz/Janai Brugger Serena: Latonia Moore Maria: Denyce Graves Sportin’ Life: Frederick Ballentine* Porgy: Eric Owens/Kevin Short Crown: Alfred Walker Jake: Ryan Speedo Green/Donovan Singletary Production: James Robinson* Set Designer: Michael Yeargan Costume Designer: Catherine Zuber Lighting Designer: Donald Holder Projection Designer: Luke Halls The worldwide copyrights in the works of George Gershwin and Ira Gershwin for this presentation are licensed by the Gershwin family. GERSHWIN is a registered trademark of Gershwin Enterprises. Porgy and Bess is a registered trademark of Porgy and Bess Enterprises. A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Dutch National Opera, Amsterdam; and English National Opera Production a gift of The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund Additional funding from Douglas Dockery Thomas Manon Jules Massenet Sep 24, 28mat, Oct 2, 5, 19, 22, 26mat ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PRESS DEPARTMENT The Metropolitan Opera Press: 212.870.7457 [email protected] 30 Lincoln Center Plaza General: 212.799.3100 metopera.org New York, NY 10023 Fax: 212.870.7606 Conductor: Maurizio Benini Manon: Lisette Oropesa Chevalier des Grieux: Michael Fabiano Guillot de Morfontaine: Carlo Bosi Lescaut: Artur Ruciński de Brétigny: Brett Polegato* Comte des Grieux: Kwangchul Youn Production: Laurent Pelly Set Designer: Chantal Thomas Costume Designer: Laurent Pelly Lighting Designer: Joël Adam Choreographer: Lionel Hoche Associate Director: Christian Räth A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Teatro alla Scala, Milan; and Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse Production a gift of The Sybil B.