New Light on the Unresolved Problem of Megalithic Habitation Sites in Kerala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 State Forest Management and Biodiversity: a Case of Kerala, India

9 State Forest Management and Biodiversity: A Case of Kerala, India Ellyn K. DAMAYANTI & MASUDA Misa 1. Introduction Republic of India is the seventh largest country in the world, covering an area of 3,287,263 km2.has large and diverse forest resources in 633,397 km2 of forest covers or 19.27% of land areas (ICFRE, 2003; FAO, 2003). Forest types in India vary from topical rainforest in northeastern India, to desert and thorn forests in Gujarat and Rajasthan; mangrove forests in West Bengal, Orissa and other coastal areas; and dry alpine forests in the western Himalaya. The most common forest types are tropical moist deciduous forest, tropical dry deciduous forests, and wet tropical evergreen forests. India has a large network of protected areas, including 89 national parks and around 497 wildlife sanctuaries (MoEF, 2005). India has long history in forest management. The first formal government approach to forest management can be traced to the enactment of the National Forest Policy of 1894, revised in 1952 and once again revised in 1988, which envisaged community involvement in the protection and regeneration of forest (MoEF, 2003). Even having large and diverse forest resources, India’s national goal is to have a minimum of one-third of the total land area of the country under forest or tree cover (MoEF, 1988). In management of state forests, the National Forest Policy, 1988 emphasizes schemes and projects, which interfere with forests that clothe slopes; catchments of rivers, lakes, and reservoirs, geologically unstable terrain and such other ecologically sensitive areas, should be severely restricted. -

A Chinese Solution to Kerala's Tourism Sector Woes

A Chinese Solution to Kerala’s Tourism Sector Woes Muraleedharan Nair Senior Fellow, CPPR Working Paper No. 001/2019 February 2019 Published in 2019 by the Centre for Public Policy Research, Kochi Centre for Public Policy Research (CPPR) First Floor, “Anitha”, Sahodaran Ayappan Road Elamkulam, Kochi, Kerala , India-682020 www.cppr.in | E-mail: [email protected] Distributed by the Centre for Public Policy Research, Kochi All rights reserved. This publication, or any part thereof shall not be reproduced in any form whatsoever without permission in writing from the author. Author Muraleedharan Nair Disclaimer: The author, who has served in various diplomatic missions in China, is a Senior Fellow with the Centre for Public Policy Research, Kochi. The opinions expressed in the report are his personal views. He has made presentations to academic audiences and written articles on similar subjects in the past, and therefore, it is natural that a few parts of the article are identical to what he has said/written earlier. A CHINESE SOLUTION TO KERALA’S TOURISM SECTOR WOES A Chinese Solution to Kerala’s Tourism Sector Woes European cities or Asian tourist destinations, lands.Therefore, they are keen to apply for North America or Australia or even Africa, new passports. wherever one goes these days, one gets to see This report will stick to the 2016 figures swarms of Chinese tourists milling around. It for the following analysis, as some of the is their sheer number – a mammoth figure – 2017 figures related to India are confusing. If rather than anything else that makes them so more than 12.2 crore Chinese visited foreign inescapably conspicuous. -

2010-11 - Term Loan

KERALA STATE BACKWARD CLASSES DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION LTD. A Govt. of Kerala Undertaking KSBCDC 2010-11 - Term Loan Name of Family Comm Gen R/ Project NMDFC Inst . Sl No. LoanNo Address Activity Sector Date Beneficiary Annual unity der U Cost Share No Income 1 010110442 Stephen S Sheela Bhavan,Vittiyodu,Parassala 25000 C M R Centering Works Business Sector 105263 89474 21/04/2010 1 2 010110443 John E Mannam Konam Milamoodu Veedu,Uzhamalakkal,Kullapada 12000 C M R Rubber Scrap Business Business Sector 105263 89474 21/04/2010 1 3 010110444 Prasanth Prashanth,Melekidarakuzhi Puthenveedu,Parasuvaikal 18250 C M R Centering Works Business Sector 105263 89474 21/04/2010 1 4 010110445 Rakhi R Aruviyode Tadatharikathu Veedu,Marangad,Marangad 30000 F R Stationery Business Sector 105263 89474 21/04/2010 1 5 010110446 Rajendran Rr Bhavan,Thekkeputhuval,Parasuvaikal 38750 C M R Stationery Business Sector 105263 89474 21/04/2010 1 6 010110447 Ratheesh S Muthiyamkonam Vadakkum Kara 20000 C M R Rental Store Business Sector 105263 89474 21/04/2010 1 Veedu,Uzhamalakkal,Panacode 7 010110448 Surendran Nadar C Kunnuvilakathu Veedu,Mondiyode,Kullapada 18000 M R Construction Work Business Sector 105263 89474 22/04/2010 1 8 010110449 Satheesh Kumar B Tadatharikathu Puthen Veedu,Muthiyam Konam,Panacode 16000 M R General Engineering Works Business Sector 105263 89474 22/04/2010 1 9 010110453 Lawrance Ls Bhavan,Kallumel Konam,Parasuvaikal 36250 C M R Stationery Business Sector 105263 89474 22/04/2010 1 10 010110457 Sanu Kumar S Valiya Vila Tadatharikathu Veedu,Kulappada,Kullapada -

RE-VISITING IRON AGE in SOUTH INDIA on 20Th August 2019 (10:00 Am) at AC Conference Hall, Vyloppilly Samskrithi Bhavan Nalanda, Thiruvananthapuram

Public Lectures RE-VISITING IRON AGE IN SOUTH INDIA On 20th August 2019 (10:00 am) At AC Conference Hall, Vyloppilly Samskrithi Bhavan Nalanda, Thiruvananthapuram Kerala Council for Historical Research Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala www.kchr.ac.in Iron Age Social Formation in South India Dr. V. Selvakumar Iron Age has been a formative phase in the early history of South India. Megalithic burials attributable to the Iron Age and Early Historic period are found all across Peninsular India and also in Sri Lanka. They are the most widely distributed archaeological remains in South India, with major similarity in material culture. Although numerous megalithic burials of the Iron Abstract Age have been identified, documented, excavated and researched in different parts of South India, the question of social formation has not been addressed sufficiently, except for a few attempts (Udaiyaravi Moorthy 1994; Gurukkal 2012). Megalithic burial practices were in vogue in the Early Historic period as well. One of the issues here pertains to the vast time span of the megalithic burials, mostly extending from the first millennium BCE to the first millennium CE, although a few of the burials could fall out of this time span. Comprehending the megalithic burials belonging to such a vast time-span has been a complex issue. The megalithic traditions witnessed diverse historical dynamics throughout their existence. In the early historic context, we get evidence for the introduction of script, coinage, political formations, Mauryan political domination and Indian Ocean exchange. The vast variations in the megalithic burial typology do suggest differences in belief systems and the nature of burial practices across South India. -

2018040471-1.Pdf

ABSTRACT OF THE AGENDA FOR THE SITTING OF REGIONAL TRANSPORT AUTHORITY ERNAKULAM PROPOSED TO BE HELD ON 16/11/2016 AT 11.00 AM AT PLANNING OFFICE CONFERENCE HALL ,GROUND FLOOR, CIVIL STATION, KAKKANAD Item No:01 G/7967/2016/E Agenda:-To consider the application for the grant of fresh regular permit in respect of a suitable stage carriage not less than 5 years with seating capacity not less than 28 in all to operate on the route Perumbavoor-Trippunithura- Kakkanad via Pattimattam- Pazhamthottam-Puthencruz- Vandippetta- Eruveli- Chottanikkara and Puthiyakavu as Ordinary Moffusil Service. Applicant:Mr.Bobas.P.K, Plamoottil House, Pazhamthottam.P.O Proposed timings Perumbavr Pattimattam Kizhak Pazhm Puthe Chotta Tripnthra Kakkanad mblm thtam ncruz nikra A D A D P P A D A D 6.56 7.11 7.31 7.51 7.55 8.25 9.35 8.55 9.05 8.45 8.25 9.51 10.21 10.31 10.46 11.06 11.26 11.40 12.1 0 1.35 1.05 1.55 2.25 4.00 3.30 4.25 5.05 6.35 6.05 5.45A 5.20 5.55D 6.50 7.20 7.30 7.45H Last Trip-Pallikkara Pass at 7.35pm Item No:02 C1/95291/2016/E Agenda: To consider the application for variation of regular permit in respect of stage carriage KL 06 D 366 operating on the route ADIVARAM-ALUVA (Via) Kadapara, Malayattoor, Neeleswaram, Kottamam, Kalady, Mattur College Jn, Nayathode, Air port road, Thuruthissery, Lakshamveedu colony, Devi Kshethram, Nedumbassery M A H S Jn ,Athani, Kunnumpuram, Desam,and Paravurkavala as ordinary Moffusil service on the strength of regular permit No.7/ 761/2008 valid upto 02/03/2018. -

India, Ceylon and Burma 1927

CATHOLIC DIRECTORY OF INDIA, CEYLON AND BURMA 1927. PUBLISHED BY THE CATHOLIC SUPPLY SOCIETY, MADRAS. PRINTED AT THE “ GOOD PASTOR ” PRESS, BROADWAY, MADRAS. Yale Divinity tibn fj New Haven. Conn M T ^ h t € ¿ 2 ( 6 vA 7 7 Nihil obstat. C. RUYGROCK, Censor Deputatus. Imprimatur: * J. AELEN, Aichbishop of Madras. Madras, Slst January 1927. PREFACE. In introducing the Catholic Directory, it is our pleasing duty to reiterate our grateful thanks for the valuable assistance and in formation received from the Prelates and the Superiors of the Missions mentioned in this book. The compilation of the Catholic Direct ory involves no small amount of labour, which, however, we believe is not spent in vain, for the Directory seems to be of great use to many working in the same field. But We would like to see the Directory develop into a still more useful publication and rendered acceptable to a wider circle. This can only come about with the practical "sympathy and active co-operation of all ^ friends and well-wishers. We again give the Catholic Directory to ¿the public, knowing that it is still incom plete, but trusting that all and everyone will ¿help us to ensure its final success. ^ MADRAS, THE COMPILER* Feast of St. Agnes, 1 9 2 7 . CONTENTS. PAGE Agra ... ... ... ... 86 iljiner ... ... ... • •• ... 92 Allahabad ... ••• ••• ••• ••• 97 Apostolic Delegation (The) ... .. ... 26 Archbishops, Bishops and Apostolic Prefects ... 449 Assam ... ... ... ... ... 177 Bombay ... ... ... ... ... 104 Éurma (Eastern) ... ... ... ... 387 Burma (Northern) ... ... ... ... 392 Burma" (Southern) ... ... ... ... 396 Calcutta ... ... ... ... ... 158 Calicut' ... ... ... ... ... 114 Catholic Indian Association of S. India ... ... 426 CHanganacberry ... ... ... ... 201 Ódchin ... ... ... ... ... 51 Coimbatore ... ... ... ... 286 Colombo .. -

Kerala History Timeline

Kerala History Timeline AD 1805 Death of Pazhassi Raja 52 St. Thomas Mission to Kerala 1809 Kundara Proclamation of Velu Thampi 68 Jews migrated to Kerala. 1809 Velu Thampi commits suicide. 630 Huang Tsang in Kerala. 1812 Kurichiya revolt against the British. 788 Birth of Sankaracharya. 1831 First census taken in Travancore 820 Death of Sankaracharya. 1834 English education started by 825 Beginning of Malayalam Era. Swatithirunal in Travancore. 851 Sulaiman in Kerala. 1847 Rajyasamacharam the first newspaper 1292 Italiyan Traveller Marcopolo reached in Malayalam, published. Kerala. 1855 Birth of Sree Narayana Guru. 1295 Kozhikode city was established 1865 Pandarappatta Proclamation 1342-1347 African traveller Ibanbatuta reached 1891 The first Legislative Assembly in Kerala. Travancore formed. Malayali Memorial 1440 Nicholo Conti in Kerala. 1895-96 Ezhava Memorial 1498 Vascoda Gama reaches Calicut. 1904 Sreemulam Praja Sabha was established. 1504 War of Cranganore (Kodungallor) be- 1920 Gandhiji's first visit to Kerala. tween Cochin and Kozhikode. 1920-21 Malabar Rebellion. 1505 First Portuguese Viceroy De Almeda 1921 First All Kerala Congress Political reached Kochi. Meeting was held at Ottapalam, under 1510 War between the Portuguese and the the leadership of T. Prakasam. Zamorin at Kozhikode. 1924 Vaikom Satyagraha 1573 Printing Press started functioning in 1928 Death of Sree Narayana Guru. Kochi and Vypinkotta. 1930 Salt Satyagraha 1599 Udayamperoor Sunahadhos. 1931 Guruvayur Satyagraha 1616 Captain Keeling reached Kerala. 1932 Nivarthana Agitation 1663 Capture of Kochi by the Dutch. 1934 Split in the congress. Rise of the Leftists 1694 Thalassery Factory established. and Rightists. 1695 Anjengo (Anchu Thengu) Factory 1935 Sri P. Krishna Pillai and Sri. -

Sl. No. Exporters Name Contact Person Designation Address 1

Sl. Company Products Exporters Name Contact Person Designation Address 1 Address 2 STATE PIN Telephone E-mail 1 Exporter Reg. No No. 1 A M K COIR A.M KAMARUDEEN PROPRIETOR 47/19, CHURCH COMPLEX, TAMIL NADU TAMIL NADU 642 001 + 91 7598471251 [email protected] Individual Firm Coir Products Merchant P-867 EXPORTS POLLACHI, 642001 om (Curled Coir Exporter Rope & Curled Coir Fibre 2 A N A MOHAMMED ISMAIL MANAGING 42/1399 CCSB ROAD, KERALA 688 001 0477 2239888 PARTNERSHIP COIR MERCHANT P-889 INTERNATIONAL HASHIM PARTNER CIVIL STATON WARD, FIRM PRODUCTS EXPORTER ALLEPPEY, KERALA - 688001 3 A.J EXPORTS S.RAMESH PROPRIETOR 44-B, DD MAIN ROAD, TAMIL NADU, TAMIL NADU INDIVIDUAL COIR FIBRE MERCHANT F-664 ARAPALAYAM, MADURAI-INDIA FIRM EXPORTER 16 4 A.J. COIR A.JAFARULLAH PARTNER S.F.NO.149/2 C, LAKSHMI POLLACHI - 642 TAMIL NADU Tel: +91- [email protected] PARTNERSHIP COIR FIBRE MANUFACTU F-554 SUPPLIERS NAGAR, 006, TAMIL 9655222786/ FIRM RER RANGASAMUTHIRAM, NADU 9344502525 EXPORTER 5 A.K BIOSYS A.SUGAVANAM PARTNER V.S.K VALAITHOTTAM, KOTTAR, TAMIL NADU 629 002 +91 9442382924 [email protected] PRIVATE COIR PITH MERCHANT P-748 COCOPEAT (INDIA) 42/2/239, ARHAMOZHI NAGERCOIL - m COMPANY COIR EXPORTER PVT LTD. ROAD, 629 002 PRODUCTS) 6 AASHIK TRADERS M.A MOHAMMED PROPRIETOR AASHIK TRADERS, 22/42, SALEM, TAMIL TAMIL NADU 636 005 +91 9443355313 [email protected] Individual Firm coir fibre Merchant F-642 ZIYAUDEEN DHARMA NAGAR 4th NADU-636005 m exporter STREET, SURAMANGALAM, 7 ABI EXPORTS N SUNDARARAJAN PROPRIETOR IInd FLOOR, RAJAM VADIPATTI TAMIL NADU 625 218 M: +91 [email protected] PROPRIETOR COIR MERCHANT P-927 ILLAM, M.P. -

IEEE Kerala News Letter 2018 Issue 1

Volume : 27 #1 Jan-Mar 2018 Volume Volume : 27 #1 A House Journal of IEEE Kerala Section http://www.ewh.ieee.org/r10/kerala Stephen William Hawking (8 January 1942 – 14 March IEEE KERALA SECTION 2018) an English theoretical physicist, cosmologist who brought the universe, black holes, space-time, and the future of our planet among other topics into the public consciousness. In 1963, when Hawking was 21, doctors diagnosed him with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a disease of the central nervous system that is currently incurable. NEWSLETTER Hawking was born on the 300th anniversary of Gali- leo’s death and died on the 139th anniversary of Ein- stein’s birth. His funeral took place at 2.00 pm on the afternoon of 31 March 2018, at Great St Mary’s Church, Cambridge. Following his cremation, his ashes will be interred in Westminster Abbey on 15 June 2018 during a Thanks- giving service. This loca- tion is next to the grave of Sir Isaac Newton and near that of Charles Darwin. Jan-Mar 2018 Jan-Mar He directed at least fifteen years before his death that the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy equation be his epitaph. Printed & Published by Prof. K. Gopalan Nair, ‘Kaivalyam’, TC 10/1368(2), Vattiyoorkavu, Tvm-695 013 on behalf of IEEE Kerala Section. Printing: Akshara Offset, Tvpm, Ph : 2471174 Editor Prof. K. Gopalan Nair, Email : [email protected], Ph : 2363232, 9446323230 Important Activities/Events 2018 Jan 3 Technical talk on Complex Networks. A Networking Perspective by Abhishek Chakraborty, IISST, Tvpm. “As a man himself sows, so he himself reaps; no man inherits Jan 6 Ockhi. -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 10.11.2019To16.11.2019

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 10.11.2019to16.11.2019 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Thazhathethil veedu, 1685/19 U/S Sankaran Vedaraplavu Muri, 10.11.2019 NOORANAD STATION 1 Biju 41/M Charummodu 279 IPC, 185 V Biju Kutty Thamarakkulam 14.00 hrs U BAIL OF MV ACT Village 1686/19 U/S Radhakrishna Sivakripa, Ulavukadu, 10.11.2019 NOORANAD STATION 2 Sree Kumar 40/M Charummodu 279 IPC, 185 V Biju n Palamel Village 19.00 hrs U BAIL OF MV ACT Kochayyathu veedu, 1687/19 U/s 11.11.2019 NOORANAD STATION 3 Arun Gopi 26/M Naduvile Muri, Charummodu 118(a) of KP V Biju U BAIL Chunakkara Village Act Kochukutty 1689/19 U/S Padinjattathil, 11.11.2019 279 IPC, 185 , NOORANAD REJUB KHAN STATION 4 Praveen Babu 25/M Charummodu Pazhanjiyoor Konam, 14.50 hrs 3(i) r/w 181 OF U SI BAIL Nooranad Village MV ACT Poikayil, Kurathikadu 1690/19 U/S Vipin V 11.11.2019 NOORANAD REJUB KHAN STATION 5 Thankachan 32/M Muri, Thekkekara Charummodu 279 IPC, 185 Thankachan 13.10 hrs U SI BAIL Village OF MV ACT Charuvayyathu Veedu, 1691/19 U/S 11.11.2019 NOORANAD REJUB KHAN STATION 6 Deepu Gopi 36/M Karimulakkal, Charummodu 279 IPC, 185 17.15 hrs U SI BAIL Chunakkara OF MV ACT Thannikkal Veedu, 1692/19 U/S Rajendran 11.11.2019 NOORANAD REJUB KHAN STATION 7 Sreeraj 27/M Kudassanadu Muri, Charummodu 279 IPC, 185 -

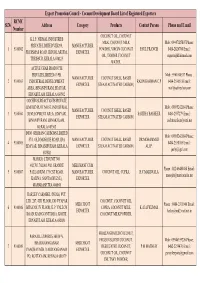

Exporters List

Export Promotion Council - Coconut Development Board List of Registered Exporters RCMC Sl.No Address Category Products Contact Person Phone and E mail Number COCONUT OIL, COCONUT K.L.F. NIRMAL INDUSTRIES MILK, COCONUT MILK Mob : 09447025807 Phone : PRIVATE LIMITED VIII/295, MANUFACTURER 1 9100002 POWDER, VIRGIN COCONUT PAUL FRANCIS 0480-2826704 Email : FR.DISMAS ROAD, IRINJALAKUDA, EXPORTER OIL, TENDER COCONUT [email protected] THRISSUR, KERALA 680125 WATER, ACTIVE CHAR PRODUCTS PRIVATE LIMITED 63/9B, Mob : 9961000337 Phone : MANUFACTURER COCONUT SHELL BASED 2 9100003 INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT RAZIN RAHMAN C.P 0484-2556518 Email : EXPORTER STEAM ACTIVATED CARBON, AREA, BINANIPURAM, EDAYAR, [email protected] ERNAKULAM, KERALA 683502 COCHIN SURFACTANTS PRIVATE LIMITED PLOT NO.63, INDUSTRIAL Mob : 09895242184 Phone : MANUFACTURER COCONUT SHELL BASED 3 9100004 DEVELOPMENT AREA, EDAYAR, SAJITHA BASHEER 0484-2557279 Email : EXPORTER STEAM ACTIVATED CARBON, BINANIPURAM, ERNAKULAM, [email protected] KERALA 683502 INDO GERMAN CARBONS LIMITED Mob : 09895242184 Phone : 57/3, OLD MOSQUE ROAD, IDA MANUFACTURER COCONUT SHELL BASED DR.MOHAMMED 4 9100005 0484-2558105 Email : EDAYAR, BINANIPURAM, KERALA EXPORTER STEAM ACTIVATED CARBON, ALI.P. [email protected] 683502 MARICO LTD UNIT NO. 402,701,702,801,902, GRANDE MERCHANT CUM Phone : 022-66480480 Email : 5 9100007 PALLADIUM, 175 CST ROAD, MANUFACTURER COCONUT OIL, COPRA, H.C MARIWALA [email protected] KALINA, SANTACRUZ (E), EXPORTER MAHARASHTRA 400098 HARLEY CARMBEL (INDIA) PVT. LTD. 287, -

Figure 1 Kochi-Muziris Biennale Poster on a Wall in Fort Kochi. the Proclamation Is an Important Marketing Message, Which Had To

Figure 1 Kochi-Muziris Biennale poster on a wall in Fort Kochi. The proclamation is an important marketing message, which had to work against much adverse publicity, reinforcing the positive message both locally and nationally that the organizers have managed to stage the first biennale in India. I noted many Kochi-Muziris Biennale posters had been torn down as part of local protests against the festival, with some being papered over, tellingly, by posters in the local Malayalam language that denounced the corruption of the biennale and its organizers. These black-and-red posters, with their pragmatic Soviet-era styling, stand out from the carefully branded biennale materials, while subverting the festival logo by adding a skull motif to it. Photograph courtesy of the author 2012 Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/cultural-politics/article-pdf/9/3/296/405126/297.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 The INDIAN BIENNALE EFFECT The Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2012 Robert E. D’Souza Abstract The Kochi-Muziris Biennale, the most recent global art biennale, was launched in Kochi in the state of Kerala, India, in 2012. This essay considers the “biennale effect,” locating it within India’s recent history of radical political modernization and in the context of the state’s attempts to establish itself in terms of internationalism and contemporaneity via the arts. Pivotal to this discussion of the biennale effect is the recognition of a growing critical discourse about the biennale format by scholars, critics, and curators. The impact of the Indian biennale on the formerly Communist city of Kochi is also explored, including photographic documentation by the author, in the context of the contradictions and paradoxes raised by India’s hosting of this global art event.