Lexical and Phonological Differences in Javanese in Probolinggo, Surabaya, and Ngawi, Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

144 PENDAHULUAN Kebumen Merupakan Salah Satu Kabupaten

PERUBAHAN MASYARAKAT PETANI MENJADI NELAYAN (STUDI KASUS DI KECAMATAN AYAH KEBUMEN) Romadi Jurusan Sejarah FIS Unnes Abstract Kebumen regency geographically can be distinguished into three areas. They are the mountain area in north, the beach area in south, and the middle area. Ayah sub district has two different areas geographically. The south and west areas are lowland (beaches), while the north and middle areas are upland. Ayah sub district consists of 18 villages, which are 5 of them be contiguous with sea, so they are called beaches areas. Among the beaches in Ayah Sub district, Logending beach, Pedalen beach, and Pasir beach are the FHQWHURI¿VKHUPHQDFWLYLWLHV/RJHQGLQJEHDFKOD\VLQZHVWDUHDERUGHURQ-HWLVEHDFKLQ&LODFDSUHJHQF\ Pasir beach lays in east area, near Karangbolong, and Pedalen beach lays between Logending beach and 3DVLUEHDFK7KHJURZWKRI¿VKHUPHQFRPPXQLW\LQ.HEXPHQVRXWKEHDFKLVXQFRPPRQEHFDXVHRILWV JHRJUDSKLFIDFWRU7KLVLVVXHPDNHVDQLQWHUHVWLQJVWXG\LQWKLVDUWLFOH7KHGDWDWRVWXG\WKH¿VKHUPHQ OLIHDUHJDLQHGWKURXJKGRFXPHQWDWLRQOLEUDU\LQWHUYLHZDQG¿HOGREVHUYDWLRQVWXGLHV7KHQDOORIWKRVH information are processed and presented descriptively, so they can be understood easily. Key words: )DUPHU¿VKHUPHQ$\DKVXEGLVWULFW PENDAHULUAN Rowokele, Sempor, Sadang, Karanggayam, Karangsambung, Padureso, Aliyan dan Kebumen merupakan salah satu Pejagoan. Sedangkan Kec. Gombong, Kabupaten di Jawa Tengah yang terletak Karanganyar, Adimulyo, Kuwarasan, di pantai Selatan. Bagian Barat berbatasan Sruweng, Kebumen, Kutowingangun, dengan Kabupaten Banyumas dan Cilacap, -

D 328 the Bioregional Principal at Banyuwangi Region Development

Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, November 26-28, 2019 The Bioregional Principal at Banyuwangi Region Development in the Context of Behavior Maintenance Ratna Darmiwati Catholic University of Darma Cendika, Surabaya, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract The tourism, natural resources, local culture and Industries with the environment are the backbone of the government's foreign development in the region exchange. The sustainable development without the environment damaging that all activities are recommended, so that between the nature and humans can be worked simultaneously. The purpose of study is maintaining the natural conditions as they are and not to be undermined by irresponsible actions. All of them are facilitated by the government, while maintaining the Osing culture community and expanding the region and make it more widely known. The maintenance of the natural existing resources should be as good as possible, so that it can be passed on future generations in well condition. All of the resources, can be redeveloped in future. The research method used qualitative-descriptive-explorative method which are sorting the datas object. The activities should have involved and relevant with the stakeholders such as the local government, the community leaders or non-governmental organizations and the broader community. The reciprocal relationships between human beings as residents and the environment are occurred as their daily life. Their life will become peaceful when the nature is domesticated. The nature will not be tampered, but arranged in form of human beings that can be moved safely and comfortably. Keywords: The Culture, Industry, Natural Resources, Tourism. -

Konsep Multimoda New Yogyakarta International Airport (Nyia)

TESIS KONSEP MULTIMODA NEW YOGYAKARTA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (NYIA) IBNU FAUZI No. Mhs.: 165.10.2569 PROGRAM STUDI MAGISTER TEKNIK SIPIL PROGRAM PASCASARJANA UNIVERITAS ATMA JAYA YOGYAKARTA 2017 i roGY`へ 1」 NIVERSITAS ATMA JAVA■ KARTA PROGRAⅣ IPASCASARJANA PR()GRANI STUDI NIACISTER TEKNIK SIPI[_ PERSITUJUAN TESIS Narna lBNU FAUZI Nomor Mahasiswa 165.10.2569ノ PSハ√TS Konsentrasi Transpottlsi ・ JudulTesis Konscp Multirlloda∬ υw i、4繊′鮨九√ε夕■α′」θ「IαJ ノ4Jψθ″σYIA) Nama Pembimbing Tattggal 'l'anda Tangiln 21//0/ あ Dr. Ir.Imarn Basuki, M.T 17 ?s/ Dr. Ir. Dlvijako Ansusanto, M.T ! lo / 2Dt7, UNIVERSITAS ATMA JAYA Y00YAKARTA PROGRAM PASCASARJANA PROGRAⅣiSTUDIL色へGISttR TEKNIK SIPIL PENGESAHAN TESIS Nama :IBNU FAUZI NomorMahasiswa :165.10.2569/PSノ ヽだTS Konsentrasi :Transpoltasi Judul Tesis :Konsep Mllltimoda Aをw】0齢ノαArarFaわ た7ηα′たンπガ メ′事η″ 鑢 `Vi■ -['*ngan Tan〔 な三 'l'zrrrrlir Nama Penguji 蟹』:ヨ Dr. Ir. Dwijoko Aususanto, M.T 44.=.策 .↑緊p・ ′夕//D"′′' Dr. Ir. Imam Basuki, M.T ふこし)´ Y. Hendra Suryadharma, Ir., M.T Plogranr Stu,-ti PROCRAM KATA PENGANTAR Puji dan Syukur penulis sampaikan ke hadirat Tuhan Yang Maha Esa atas rahmat dan kasih-Nya, sehingga penulis dapat menyelesaikan Tesis ini. Adapun tujuan penulisan Tesis dengan judul “KONSEP MULTIMODA NEW YOGYAKARTA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (NYIA)” adalah untuk melengkapi syarat untuk menyelesaikan jenjang pendidikan tinggi Program Master (S-2) di Program Pascasarjana Program Studi Magister Teknik Sipil Universitas Atma Jaya Yogyakarta. Penulis menyadari bahwa tugas akhir ini tidak mungkin dapat diselesaikan tanpa bantuan dari berbagai pihak. Oleh karena itu, dalam kesempatan ini penulis mengucapkan terima kasih kepada pihak-pihak yang telah membantu penulis dalam menyelesaikan penulisan Tesis, antara lain: 1. -

Mapping of Regional Inequality in East Java Province

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 8, ISSUE 03, MARCH 2019 ISSN 2277-8616 Mapping Of Regional Inequality In East Java Province Duwi Yunitasari, Jejeet Zakaria Firmansayah Abstract: The research objective was to map the inequality between regions in 5 (five) Regional Coordination Areas (Bakorwil) of East Java Province. The research data uses secondary data obtained from the Central Bureau of Statistics and related institutions in each region of the Regional Office in East Java Province. The analysis used in this study is the Klassen Typology using time series data for 2010-2016. The results of the analysis show that: a. based on Typology Klassen Bakorwil I from ten districts / cities there are eight districts / cities that are in relatively disadvantaged areas; b. based on the typology of Klassen Bakorwil II from eight districts / cities there are four districts / cities that are in relatively disadvantaged areas; c. based on the typology of Klassen Bakorwil III from nine districts / cities there are three districts / cities that are in relatively lagging regions; d. based on the Typology of Klassen Bakorwil IV from 4 districts / cities there are three districts / cities that are in relatively lagging regions; and e. based on the Typology of Klassen Bakorwil V from seven districts / cities there are five districts / cities that are in relatively disadvantaged areas. Keywords: economic growth, income inequality, Klassen typology, regional coordination, East Java. INTRODUCTION Development inequality between regencies / cities in East East Java is an area of accelerated economic growth in Java Province can be seen from the average GRDP Indonesia. According to economic performance data distribution of Regency / City GRDP at 2010 Constant (2015), East Java is the second largest contributing Prices in Table 1.2. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION This Chapter Presents Five Subtopics

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION This chapter presents five subtopics, namely; research background, research questions, research objective, research limitation and research significance. 1.1 Research Background Language is essentially a speech of the mind and feeling of human beings on a regular basis, which uses sound as a tool (Ministry of National Education, 2005: 3). Language is a structure and meaning that is free from its users, as a sign that concludes a goal (HarunRasyid, Mansyur&Suratno 2009: 126). Language is a particular kind of system that is used to transfer the information and it is an encoding and decoding activity in order to get information (Seken, 1992). The number of languages in the world varies between (6,000-7,000) languages. However, the right estimates depend on arbitrary changes between various languages and dialects. Natural language is sign language but each language can be encoded into a second medium using audio, visual, or touch stimuli, for example, in the form of graphics, braille, or whistles. This is because human language is an independent modality. All languages depend on a symbiotic process to connect signals with certain meanings. In Indonesia there are many very beautiful cities and many tribes that have different languages and are very interesting to learn. One of the cities to be studied is Banyuwangi Regency. Banyuwangi Regency is a district of East Java province in Indonesia. This district is located in the easternmost part of Java Island. Banyuwangi is separated by the Bali Strait from Bali. Banyuwangi City is the administrative capital. The name Banyuwangi is the Javanese language for "fragrant water", which is connected with Javanese folklore on the Tanjung. -

School Counseling Services Information System Optimization in Multi-Level School at Surabaya

School Counseling Services Information System Optimization in Multi-Level School at Surabaya Susana Limanto*, Andre*, Dhiani Tresna Absari, Sholeh Hadi Setyawan Informatics Engineering Department, University of Surabaya, Surabaya 60293, East Java, Indonesia Raya Kalirungkut 60293, Surabaya, East Java, Indonesia. Phone : 62-031-2981395 *Corresponding author Email:[email protected], [email protected] Received: 30 August 2016 Accepted: 30 May 2017 The success criteria of formal education of a student are not only determined by academic ability, but also by attitude, interest, and value that is possessed by the student. Therefore, the School Counseling Services (SCS) becomes more important part of the school, to help students to accept and understand themselves and their environments. The SCS can also drive the students to self-direct and self-adapt to the demands of their environments. By providing a good service, SCS can help students to study and reach better achievement in education, social, and their career related to their interest and their talent. The goal of this research is to develop a software to optimize process of SCS used in multi-level school at Surabaya. Software is developed based on analysis and grand design from previous research. Evaluation of Information System SCS conducted by distributing survey to all three types of users, which are: Classroom Teacher, Counseling Services Teacher, and parents. The evaluation results proves that at least 75% of users agreed that the SCS able to improve teacher performances, improve capability of collaboration, each user understand its each individual roles, and maintain communication between different users. Furthermore, SCS IS could be expanded for more better and optimum service solution. -

Situation Update Response to COVID-19 in Indonesia As of 18 January 2021

Situation Update Response to COVID-19 in Indonesia As of 18 January 2021 As of 18 January, the Indonesian Government has announced 917,015 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in all 34 provinces in Indonesia, with 144,798 active cases, 26,282 deaths, and 745,935 people that have recovered from the illness. The government has also reported 77,579 suspected cases. The number of confirmed daily positive cases of COVID-19 in Indonesia reached a new high during four consecutive days on 13-16 January since the first positive coronavirus case was announced by the Government in early March 2020. Total daily numbers were 11,278 confirmed cases on 13 January, 11,557 cases on 14 January, 12,818 cases on 15 January, and 14,224 cases on 16 January. The Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) has declared the COVID-19 Vaccine by Sinovac as halal. The declaration was stipulated in a fatwa that was issued on 8 January. On 11 January, the Food and Drug Administration (BPOM) issued the emergency use authorization for the vaccine. Following these two decisions, the COVID-19 vaccination program in Indonesia began on 13 January, with the President of the Republic of Indonesia being first to be vaccinated. To control the increase in the number of cases of COVID-19, the Government has imposed restrictions on community activities from January 11 to 25. The restrictions are carried out for areas in Java and Bali that meet predetermined parameters, namely rates of deaths, recovered cases, active cases and hospitals occupancy. The regions are determined by the governors in seven provinces: 1. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae PERSONAL DETAILS Name : Khuliyah Candraning Diyanah, S.KM., M.KL. Office : Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Airlangga, Address Surabaya, Indonesia Email : [email protected] EDUCATION Universitas Airlangga PROFILE 2004 – 2008 Public Health – Bachelor Lecturer Universitas Airlangga 2009 – 2011 Environmental Health Management – Master https://www.linkedin.com/in/khuliyah- candraning-diyanah-222227145/ RESEARCH INTERESTS https://scholar.google.co.id/citations?u Environmental Health and Management, Climate change and Health, ser=91o2dD8AAAAJ&hl=id Environmental Pollution, Environmental sanitation https://www.researchgate.net/profile/ Khuliyah_Diyanah RESEARCH EXPERIENCES https://independent.academia.edu/Kh uliyahCandraningDiyanah • The Effects of LPS Endotoxins in Rice Dust on Lung Physiology Operators, 2012, funded by RKAT • Analysis of Determination of Indicators of causes and preparation of DO TB Model / Minimization System Sidoarjo Districts, 2012, funded by Bappeda Sidoarjo Districts • Measurement of Community Reading Interest in East Java Province, 2013, funded by Bapersip East Java Province • Preparation of the Mojokerto City General Hospital Master Plan, 2013, funded by the Mojokerto City Hospital • Calculation of Unit Cost of Ngawi Regency General Hospital, 2013, funded by General Hospital Ngawi Districts • Occurrence Rate of IgM and IgG Positive Toxoplasm and Its Relationship with Individual Hygiene of Semampir RPH Employees, Surabaya, 2013, funded by RKAT • Unit Cost Calculation of Syaiful Anwar Malang -

The Influence of Resettlement of the Capital of Probolinggo Regency Toward Service Quality of Police Record (SKCK) (Study in Probolinggo Resort Police)

1411-0199 Wacana Vol. 16, No. 3 (2013) ISSN : E-ISSN : 2338-1884 The Influence of Resettlement of the Capital of Probolinggo Regency toward Service Quality of Police Record (SKCK) (Study in Probolinggo Resort Police) Erlinda Puspitasari1*, Mardiyono2, Hermawan2 1Fastrack Master Program, Faculty of Administrative Sciences, University of Brawijaya, Malang 2Faculty of Administrative Sciences, University of Brawijaya, Malang Abstract This study examined the influence of resettlement of the capital of Probolinggo Regency toward service quality of Police Record (SKCK) in Probolinggo Resort Police. Probolinggo Resort Police (POLRES) is one government agencies that experiencing resettlement of the location from Probolinggo City to Kraksaan district. It is expected that by this resettlement, public service processes would bec}u Z v ]v Z]PZ µo]Ç[X The study used quantitative research method with explanatory approach to test the hypothesis that has been set. Dependent variable in this study are resettlement of the capital of regency (X) with the variables: affordability, recoverability and replicability. While the dependent variable in this study are the service quality of Police Record (SKCK) (Y) with the indicators: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy. The study used multiple linear regression method of analysis. The study revealed that the resettlement of the capital of regency variable (X) which consist of three variables such as affordability (X1), recoverability (X2) and replicability variable (X3) influence significantly toward service quality of the Police Record (SKCK) in Probolinggo Resort Police (POLRES). Keywords: Police Record (SKCK), Probolinggo Resort Police, Service Quality, The Resettlement, The Capital of Regency. INTRODUCTION * government wheel. This is in accordance with City is a human agglomeration in a relative Rawat [2] stated that "Capital cities play a vital restricted space. -

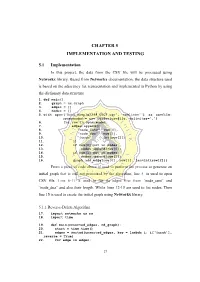

Chapter 5 Implementation and Testing

CHAPTER 5 IMPLEMENTATION AND TESTING 5.1 Implementation In this project, the data from the CSV file will be processed using Networkx library. Based from Networkx documentation, the data structure used is based on the adjacency list representation and implemented in Python by using the dictionary data structure. 1. def main(): 2. graph = nx.Graph 3. edges = [] 4. nodes = [] 5. with open('Data_Sample2/49_USCT.csv', newline='') as csvfile: spamreader = csv.reader(csvfile, delimiter=',') 6. for row in spamreader: 7. edges.append({ 8. “node_satu”: row[0], 9. “node_dua” : row[1], 10. “jarak” : int(row[2]) 11. }) 12. if row[0] not in nodes: 13. nodes.append(row[0]) 14. if row[1] not in nodes: 15. nodes.append(row[1]) 16. graph.add_edge(row[0], row[1], len=int(row[2])) From a piece of code above is used to perform the process to generate an initial graph that is still not processed by the algorithm, line 5 is used to open CSV file. Line 6-11 is used to list its edges first from “node_satu” and “node_dua” and also their length. While lines 12-15 are used to list nodes. Then line 15 is used to create the initial graph using Networkx library. 5.1.1 Reverse-Delete Algorithm 17. import networkx as nx 18. import time 19. def main(unsorted_edges, rd_graph): 20. start = time.time() 21. edges = sorted(unsorted_edges, key = lambda i: i[‘jarak’], reverse = True) 22. for edge in edges: 27 23. rd_graph.remove_edge(edge[‘node_satu’], edge[‘node_dua’]) 24. is_connected = nx.is_connected(rd_graph) 25. if not is_connected: 26. -

Strengthening the Disaster Resilience of Indonesian Cities – a Policy Note

SEPTEMBER 2019 STRENGTHENING THE Public Disclosure Authorized DISASTER RESILIENCE OF INDONESIAN CITIES – A POLICY NOTE Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Background Urbanization Time to ACT: Realizing Paper Flagship Report Indonesia’s Urban Potential Public Disclosure Authorized STRENGTHENING THE DISASTER RESILIENCE OF INDONESIAN CITIES – A POLICY NOTE Urban floods have significant impacts on the livelihoods and mobility of Indonesians, affecting access to employment opportunities and disrupting local economies. (photos: Dani Daniar, Jakarta) Acknowledgement This note was prepared by World Bank staff and consultants as input into the Bank’s Indonesia Urbanization Flagship report, Time to ACT: Realizing Indonesia’s Urban Potential, which can be accessed here: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31304. The World Bank team was led by Jolanta Kryspin-Watson, Lead Disaster Risk Management Specialist, Jian Vun, Infrastructure Specialist, Zuzana Stanton-Geddes, Disaster Risk Management Specialist, and Gian Sandosh Semadeni, Disaster Risk Management Consultant. The paper was peer reviewed by World Bank staff including Alanna Simpson, Senior Disaster Risk Management Specialist, Abigail Baca, Senior Financial Officer, and Brenden Jongman, Young Professional. The background work, including technical analysis of flood risk, for this report received financial support from the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) through the World Bank Indonesia Sustainable Urbanization (IDSUN) Multi-Donor Trust Fund. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. ii STRENGTHENING THE DISASTER RESILIENCE OF INDONESIAN CITIES – A POLICY NOTE THE WORLD BANK Table of Contents 1. -

Local Tourism? Why Not! Integrating Tourism Geographic Spatial in Ngawi Regency, Indonesia

Modern Applied Science; Vol. 14, No. 9; 2020 ISSN 1913-1844 E-ISSN 1913-1852 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Local Tourism? Why Not! Integrating Tourism Geographic Spatial in Ngawi Regency, Indonesia Dyah E Setyowati1, Yani Antariksa1, Endri Haryati1, Haryono2 & Indra P P Salmon3 1Department of Science Management, Sekolah Tinggi Ilmu Ekonomi Bisnis Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia 2Department of Economic Development, Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Bhayangkara, Surabaya, Indonesia 3Department of Public Administration, Faculty of Social and Political Science, University of Bhayangkara, Surabaya, Indonesia Correspondence: Indra P P Salmon, Department of Public Administration, Faculty of Social and Political Science, University of Bhayangkara, Indonesia. Received: February 28, 2020 Accepted: August 24, 2020 Online Published: August 27, 2020 doi:10.5539/mas.v14n9p1 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v14n9p1 Abstract Ngawi Regency has a diversity of tourist destinations supported by the accessibility of strategic areas, but there are problems in the form of tourist visits opportunity that are still not optimal. The strategy that must be carried out is to design a tourist destination design in a strategic access corridor between the Special Region of Yogyakarta (DIY), Solo, Ngawi, and Surabaya (Yogya-Solo-Ngawi-Surabaya) and open access to local tourism information. This strategy is also applied on the basis of the strategic accessibility of Ngawi Regency which is located between the northern coast lines that connect various tourist attractions. The purpose of this study is to map each area of tourist destinations and connectivity within an integrated area, and; designing a spatial structuring model for integrated tourist destination areas in Ngawi Regency.