Gendered Pleasures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Videogames in the Museum: Participation, Possibility and Play in Curating Meaningful Visitor Experiences

Videogames in the museum: participation, possibility and play in curating meaningful visitor experiences Gregor White Lynn Parker This paper was presented at AAH 2016 - 42nd Annual Conference & Book fair, University of Edinburgh, 7-9 April 2016 White, G. & Love, L. (2016) ‘Videogames in the museum: participation, possibility and play in curating meaningful visitor experiences’, Paper presented at Association of Art Historians 2016 Annual Conference and Bookfair, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, 7-9 April 2016. Videogames in the Museum: Participation, possibility and play in curating meaningful visitor experiences. Professor Gregor White Head of School of Arts, Media and Computer Games, Abertay University, Dundee, UK Email: [email protected] Lynn Parker Programme Leader, Computer Arts, Abertay University, Dundee, UK Email: [email protected] Keywords Videogames, games design, curators, museums, exhibition, agency, participation, rules, play, possibility space, co-creation, meaning-making Abstract In 2014 Videogames in the Museum [1] engaged with creative practitioners, games designers, curators and museums professionals to debate and explore the challenges of collecting and exhibiting videogames and games design. Discussions around authorship in games and games development, the transformative effect of the gallery on the cultural reception and significance of videogames led to the exploration of participatory modes and playful experiences that might more effectively expose the designer’s intent and enhance the nature of our experience as visitors and players. In proposing a participatory mode for the exhibition of videogames this article suggests an approach to exhibition and event design that attempts to resolve tensions between traditions of passive consumption of curated collections and active participation in meaning making using theoretical models from games analysis and criticism and the conceit of game and museum spaces as analogous rules based environments. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

The Videogame Style Guide and Reference Manual

The International Game Journalists Association and Games Press Present THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL DAVID THOMAS KYLE ORLAND SCOTT STEINBERG EDITED BY SCOTT JONES AND SHANA HERTZ THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL All Rights Reserved © 2007 by Power Play Publishing—ISBN 978-1-4303-1305-2 No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. Disclaimer The authors of this book have made every reasonable effort to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information contained in the guide. Due to the nature of this work, editorial decisions about proper usage may not reflect specific business or legal uses. Neither the authors nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible to any person or entity with respects to any loss or damages arising from use of this manuscript. FOR WORK-RELATED DISCUSSION, OR TO CONTRIBUTE TO FUTURE STYLE GUIDE UPDATES: WWW.IGJA.ORG TO INSTANTLY REACH 22,000+ GAME JOURNALISTS, OR CUSTOM ONLINE PRESSROOMS: WWW.GAMESPRESS.COM TO ORDER ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL PLEASE VISIT: WWW.GAMESTYLEGUIDE.COM ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our thanks go out to the following people, without whom this book would not be possible: Matteo Bittanti, Brian Crecente, Mia Consalvo, John Davison, Libe Goad, Marc Saltzman, and Dean Takahashi for editorial review and input. Dan Hsu for the foreword. James Brightman for his support. Meghan Gallery for the front cover design. -

Casual Resistance: a Longitudinal Case Study of Video Gaming's Gendered

Running Head: CASUAL RESISTANCE Casual resistance: A longitudinal case study of video gaming’s gendered construction and related audience perceptions Amanda C. Cote This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Oxford Academic in Journal of Communication on August 4, 2020, available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa028 . Abstract: Many media are associated with masculinity or femininity and male or female audiences, which links them to broader power structures around gender. Media scholars thus must understand how gendered constructions develop and change, and what they mean for audiences. This article addresses these questions through longitudinal, in-depth interviews with female video gamers (2012-2018), conducted as the rise of casual video games potentially started redefining gaming’s historical masculinization. Analysis shows that participants have negotiated relationships with casualness. While many celebrate casual games’ potential for welcoming new audiences, others resist casual’s influence to safeguard their self-identification as gamers. These results highlight how a medium’s gendered construction may not be salient to consumers, who carefully navigate divides between their own and industrially-designed identities, but can simultaneously reaffirm existing power structures. Further, how participants’ views change over time emphasizes communication’s ongoing need for longitudinal audience studies that address questions of media, identity, and inclusion. Keywords: Video games, gender, game studies, feminist media studies, hegemony, casual games, in-depth interviews, longitudinal audience studies CASUAL RESISTANCE 2 Casual resistance: A longitudinal case study of video gaming’s gendered construction and related audience perceptions From comic books to soap operas, many media are gendered, associated with masculinity or femininity and with male or female audiences. -

Effects of Art Styles on Video Game Narratives

Effects of Art Styles on Video Game Narratives UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Department of Future Technologies Master's Thesis July 2018 Leena Hölttä UNIVERSITY OF TURKU Department of Future Technologies HÖLTTÄ, LEENA Effects of Art Styles on Video Game Narratives Master's thesis, 76 pages, 29 appendix pages Computer Science August 2018 The effect of an art style on a video game's narrative is not widely studied and not much is known about how the general player base views the topic. This thesis attempts to answer this question through the use of two different surveys, a general theory related one, and one based upon images and categorization and a visual novel based interview that aims at gaining a further understanding of the subject. The general results point to the art style creating and emphasizing a narrative's mood and greatly enhancing the player experience. Based on these results a simple framework ASGDF was created to help beginning art directors and designers to create the most fitting style for their narrative. Key words: video games, art style, art, narrative, games TURUN YLIOPISTO Tulevaisuuden teknologioiden laitos HÖLTTÄ, LEENA Taidetyylien vaikutus videopelien narratiiviin Pro gradu -tutkielma, 76 s., 29 liites. Tietojenkäsittelytiede Elokuu 2018 Taidetyylien vaikutus videopelien narratiiviin ei ole laajasti tutkittu aihe, eikä ole laajasti tiedossa miten yleinen pelaajakunta näkee aiheen. Tämä tutkielma pyrkii vastaamaan tähän kysymykseen kahden eri kyselyn avulla, joista toinen on teoriaan perustuva kysely, ja toinen kuvien kategorisointiin perustuva kysely. Myös visuaalinovelliin perustuvaa haastattelua käytettiin tutkimuskysymyksen tutkimiseen. Yleiset tulokset viittaavat siihen, että taidetyyli vaikuttaa narratiivin tunnelmaan ja korostaa pelaajan kokemusta. -

A Casual Game Benjamin Peake Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester Polytechnic Institute Digital WPI Major Qualifying Projects (All Years) Major Qualifying Projects April 2016 Storybook - A Casual Game Benjamin Peake Worcester Polytechnic Institute Connor Geoffrey Porell Worcester Polytechnic Institute Nathaniel Michael Bryant Worcester Polytechnic Institute William Emory Blackstone Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/mqp-all Repository Citation Peake, B., Porell, C. G., Bryant, N. M., & Blackstone, W. E. (2016). Storybook - A Casual Game. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/mqp-all/2848 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Major Qualifying Projects at Digital WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Major Qualifying Projects (All Years) by an authorized administrator of Digital WPI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Storybook - A Casual Game Emory Blackstone, Nathan Bryant, Benny Peake, Connor Porell April 27, 2016 A Major Qualifying Project Report: submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by Emory Blackstone Nathan Bryant Benny Peake Connor Porell Date: April 2016 Approved: Professor David Finkel, Advisor Professor Britton Snyder, Co-Advisor This report represents the work of one or more WPI undergraduate students. Submitted to the faculty as evidence of completion of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial -

What Is Casual Gaming?

CHAPTER ONE What Is Casual Gaming? Over the past several years, the term “ casual game ” has been bandied about quite a bit. It gets used to describe so many different types of games that the definition has become rather blurred. But if we look at all of the ways that “ casual ” gets used, we can begin to tease out common elements that inform the design of these games: ● Rules and goals must be clear. ● Players need to be able to quickly reach proficiency. ● Casual game play adapts to a player’s life and schedule. ● Game concepts borrow familiar content and themes from life. While all game design should take these issues into account, these elements are of particular importance if you want to reach a broad audience beyond traditional gamers. This book will look at elements that a wide array of casual games share and draw out common lessons for approaching game design. Hopefully it will be of use not just to casual game designers, but to all game designers and even general experience designers as well. Everywhere you look these days, you see impact of casual games. More than 200 million people play casual games on the Internet, according to the Casual Games Association. This audience generated revenues in excess of $2.25 billion in 2007. 1 This may seem meager compared to the $41 billion posted by the entire game indus- try worldwide,2 but casual games currently rank as one of the fastest growing sec- tors of the game industry. As growth in the rest of the industry stagnated, the casual downloadable market barreled ahead. -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Video Game Trader Magazine & Price Guide

Winter 2009/2010 Issue #14 4 Trading Thoughts 20 Hidden Gems Blue‘s Journey (Neo Geo) Video Game Flashback Dragon‘s Lair (NES) Hidden Gems 8 NES Archives p. 20 19 Page Turners Wrecking Crew Vintage Games 9 Retro Reviews 40 Made in Japan Coin-Op.TV Volume 2 (DVD) Twinkle Star Sprites Alf (Sega Master System) VectrexMad! AutoFire Dongle (Vectrex) 41 Video Game Programming ROM Hacking Part 2 11Homebrew Reviews Ultimate Frogger Championship (NES) 42 Six Feet Under Phantasm (Atari 2600) Accessories Mad Bodies (Atari Jaguar) 44 Just 4 Qix Qix 46 Press Start Comic Michael Thomasson’s Just 4 Qix 5 Bubsy: What Could Possibly Go Wrong? p. 44 6 Spike: Alive and Well in the land of Vectors 14 Special Book Preview: Classic Home Video Games (1985-1988) 43 Token Appreciation Altered Beast 22 Prices for popular consoles from the Atari 2600 Six Feet Under to Sony PlayStation. Now includes 3DO & Complete p. 42 Game Lists! Advertise with Video Game Trader! Multiple run discounts of up to 25% apply THIS ISSUES CONTRIBUTORS: when you run your ad for consecutive Dustin Gulley Brett Weiss Ad Deadlines are 12 Noon Eastern months. Email for full details or visit our ad- Jim Combs Pat “Coldguy” December 1, 2009 (for Issue #15 Spring vertising page on videogametrader.com. Kevin H Gerard Buchko 2010) Agents J & K Dick Ward February 1, 2009(for Issue #16 Summer Video Game Trader can help create your ad- Michael Thomasson John Hancock 2010) vertisement. Email us with your requirements for a price quote. P. Ian Nicholson Peter G NEW!! Low, Full Color, Advertising Rates! -

The Dreamcast, Console of the Avant-Garde

Loading… The Journal of the Canadian Game Studies Association Vol 6(9): 82-99 http://loading.gamestudies.ca The Dreamcast, Console of the Avant-Garde Nick Montfort Mia Consalvo Massachusetts Institute of Technology Concordia University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract We argue that the Dreamcast hosted a remarkable amount of videogame development that went beyond the odd and unusual and is interesting when considered as avant-garde. After characterizing the avant-garde, we investigate reasons that Sega's position within the industry and their policies may have facilitated development that expressed itself in this way and was received by gamers using terms that are associated with avant-garde work. We describe five Dreamcast games (Jet Grind Radio, Space Channel 5, Rez, Seaman, and SGGG) and explain how the advances made by these industrially productions are related to the 20th century avant- garde's lesser advances in the arts. We conclude by considering the contributions to gaming that were made on the Dreamcast and the areas of inquiry that remain to be explored by console videogame developers today. Author Keywords Aesthetics; art; avant-garde; commerce; console games; Dreamcast; game studios; platforms; politics; Sega; Tetsuya Mizuguchi Introduction A platform can facilitate new types of videogame development and can expand the concept of videogaming. The Dreamcast, however brief its commercial life, was a platform that allowed for such work to happen and that accomplished this. It is not just that there were a large number of weird or unusual games developed during the short commercial life of this platform. We argue, rather, that avant-garde videogame development happened on the Dreamcast, even though this development occurred in industrial rather than "indie" or art contexts. -

Super Smash Bros. Tournament Rules

SUPER SMASH BROS. TOURNAMENT RULES General The Intramurals Participant Handbook will govern all aspects of play not considered playing rules of the sport. Participants are expected to follow the Handbook rules of conduct as well as the sport-specific rules outlined below. The Handbook is available at und.edu/intramurals. Key Handbook items include: • Registration & Payment – Handbook pg. 7 • Captain Responsibilities – Handbook pg. 9 • Team Name Requirements – Handbook pg. 10 • Playoff Requirements – Handbook pg. 12 • Default/Forfeit Instructions and Consequences – Handbook pg. 14 • Participant Eligibility/ID Requirements – Handbook pg. 15 • Adding Players to Roster/Participation Limits – Handbook pg. 18 • Team/Participant Conduct – Handbook pg. 21 • Nexus Policies – UND.edu/esports Schedules Schedules for league play are posted online through wellnessregistration.und.edu. Facility All games will be played at the Wellness Center Esports Nexus, or at remote locations. Questions Please feel free to contact UND Esports Nexus staff with any questions or concerns. Mike Wozniak Coordinator of Campus 701-777-3256 [email protected] Recreation Seb Reese Esports Program Manager 701-777-0212 [email protected] Wellness Center 701-777-9355 Revised 8/21/2020 UND Super Smash Bros. Rules Page 1 Equipment • We will be using Wellness & Health Promotion Nintendo Switch consoles, with the possibility of a loaned console if needed to facilitate competition. • We will have Joy-Cons and Switch Pro controllers to use if needed, however participants will be allowed to bring their own controllers. • Allowed controllers are: • GameCube • Switch Pro • Joy-Con • SmashBox • If you have another controller you wish to use, it will need to be approved by the Esports staff. -

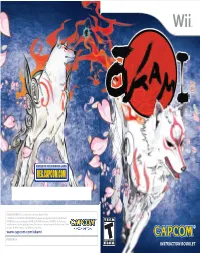

Instruction Booklet

CAPCOM ENTERTAINMENT, INC., 800 Concar Drive, Suite 300, San Mateo, CA 94402 © CAPCOM CO., LTD. 2006, 2008 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Wii development by Ready At Dawn Studios LLC. CAPCOM and the CAPCOM LOGO are registered trademarks of CAPCOM CO., LTD. ŌKAMI is a trademark of CAPCOM CO., LTD. The typefaces included herein are solely developed by DynaComware. The rating icon is a registered trademark of the Entertainment Software Association. All other trademarks are owned by their respective owners. www.capcom.com/okami PRINTED IN USA INSTRUCTION BOOKLET ESRB on Front: 14 x 21 mm OKAMI: Wii Manual Cover - Round 5 Prepared by Eclipse Advertising on: February 28, 2008 PLEASE CAREFULLY READ THE Wii™ OPERATIONS MANUAL COMPLETELY BEFORE USING YOUR Wii HARDWARE SYSTEM, GAME DISC OR ACCESSORY. THIS MANUAL CONTAINS IMPORTANT The Official Seal is your assurance that this product is licensed or manufactured by HEALTH AND SAFETY INFORMATION. Nintendo. Always look for this seal when buying video game systems, accessories, games and related products. IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION: READ THE FOLLOWING WARNINGS BEFORE YOU OR YOUR CHILD PLAY VIDEO GAMES. Dolby, Pro Logic, and the double-D symbol are trademarks of Dolby Laboratories. Manufactured under license from Dolby Laboratories. WARNING – Seizures This game is presented in Dolby Pro Logic II. To play games that carry the Dolby Pro Logic II logo in surround sound, you will need a Dolby Pro Logic II, Dolby Pro Logic or Dolby Pro Logic IIx receiver. These • Some people (about 1 in 4000) may have seizures or blackouts triggered by light flashes or receivers are sold separately.