The Discourses of Philoxenos of Mabbug Translated by Robert A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Education and Class Formation in Early Judaism

COLONIAL EDUCATION AND CLASS FORMATION IN EARLY JUDAISM: A POSTCOLONIAL READING by Royce Manojkumar Victor Bachelor of Science, 1988 Calicut University, Kerala, India Bachelor of Divinity, 1994 United Theological College Bangalore, India Master of Theology, 1999 Senate of Serampore College Serampore, India Dissertation Presented to the Faulty of the Brite Divinity School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biblical Interpretation Fort Worth, Texas U.S.A. May 2007 ii iii © 2007 by Royce Manojkumar Victor Acknowledgments It is a delight to have the opportunity to thank the people who have helped me with the writing of this dissertation. Right from beginning to the completion of this study, Prof. Leo Perdue, my dissertation advisor and my guru persevered with me, giving apt guidance and judicious criticism at every stage. He encouraged me to formulate my own questions, map out my own quest, and seek the answers that would help me understand and contextualize my beliefs, practices, and identity. My profuse thanks to him. I also wish to thank Prof. David Balch and Prof. Carolyn Osiek, my readers, for their invaluable comments and scholarly suggestions to make this study a success. I am fortunate to receive the wholehearted support and encouragement of Bishop George Isaac in this endeavor, and I am filled with gratitude to him. With deep sense of gratitude, I want to acknowledge the inestimable help and generous support of my friends from the Grace Presbytery of PC(USA), who helped me to complete my studies in the United States. In particular, I wish to thank Rev. -

Roman-Barbarian Marriages in the Late Empire R.C

ROMAN-BARBARIAN MARRIAGES IN THE LATE EMPIRE R.C. Blockley In 1964 Rosario Soraci published a study of conubia between Romans and Germans from the fourth to the sixth century A.D.1 Although the title of the work might suggest that its concern was to be with such marriages through- out the period, in fact its aim was much more restricted. Beginning with a law issued by Valentinian I in 370 or 373 to the magister equitum Theodosius (C.Th. 3.14.1), which banned on pain of death all marriages between Roman pro- vincials and barbarae or gentiles, Soraci, after assessing the context and intent of the law, proceeded to discuss its influence upon the practices of the Germanic kingdoms which succeeded the Roman Empire in the West. The text of the law reads: Nulli provineialium, cuiuscumque ordinis aut loci fuerit, cum bar- bara sit uxore coniugium, nec ulli gentilium provinciales femina copuletur. Quod si quae inter provinciales atque gentiles adfinitates ex huiusmodi nuptiis extiterit, quod in his suspectum vel noxium detegitur, capitaliter expietur. This was regarded by Soraci not as a general banning law but rather as a lim- ited attempt, in the context of current hostilities with the Alamanni, to keep those barbarians serving the Empire (gentiles)isolated from the general Roman 2 populace. The German lawmakers, however, exemplified by Alaric in his 63 64 interpretatio,3 took it as a general banning law and applied it in this spir- it, so that it became the basis for the prohibition under the Germanic king- doms of intermarriage between Romans and Germans. -

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; Proquest Pg

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; ProQuest pg. 159 Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion R. D. Milns SOME TIME between the battle of Gaugamela and the battle of A the Hydaspes the number of battalions in the Macedonian phalanx was raised from six to seven.1 This much is clear; what is not certain is when the new formation came into being. Berve2 believes that the introduction took place at Susa in 331 B.C. He bases his belief on two facts: (a) the arrival of 6,000 Macedonian infantry and 500 Macedonian cavalry under Amyntas, son of Andromenes, when the King was either near or at Susa;3 (b) the appearance of Philotas (not the son of Parmenion) as a battalion leader shortly afterwards at the Persian Gates.4 Tarn, in his discussion of the phalanx,5 believes that the seventh battalion was not created until 328/7, when Alexander was at Bactra, the new battalion being that of Cleitus "the White".6 Berve is re jected on the grounds: (a) that Arrian (3.16.11) says that Amyntas' reinforcements were "inserted into the existing (six) battalions KC1:TCt. e8vr(; (b) that Philotas has in fact taken over the command of Perdiccas' battalion, Perdiccas having been "promoted to the Staff ... doubtless after the battle" (i.e. Gaugamela).7 The seventh battalion was formed, he believes, from reinforcements from Macedonia who reached Alexander at Nautaca.8 Now all of Tarn's arguments are open to objection; and I shall treat them in the order they are presented above. -

Matthew 16:18 in the Philoxenian Version

1 Matthew 16:18 in the Philoxenian Version Peter A.L. Hill Flinders University, Adelaide, South Australia1 1. Little now remains of the Syriac Philoxenian version (PHIL) of the New Testament. Commissioned by Philoxenus of Mabbug and completed in 508/509 by Polycarp, his chorepiscopus, PHIL was based upon the Peshitta (P) and in turn became the Grundtext for the Harklean New Testament (H) completed in 615/616.2 Apart from an edition of the Minor Catholic Epistles thought to be PHIL,3 remnants of the version remain in the scripture quotations found in the later writings of Philoxenus. In this article I will explore one of these quotations, namely Mt 16:18. Historically, considerable controversy has surrounded the interpretation of this verse; thus any additional data are of interest. First, however, a little background regarding the identification of PHIL quotations in Philoxenus’ works. Identifying PHIL Quotations in the Works of Philoxenus 2. It was Günther Zuntz (1945) who first examined the works of Philoxenus with a view to discovering PHIL readings. However, notwithstanding some excellent observations, Zuntz’s methodology was flawed, in part by his failure to distinguish between the array of Graecized citations scattered across a number of Philoxenus’ writings and the genuine PHIL quotations which occur only in the later writings.4 Subsequently, Arthur Vööbus (1954) continued the investigation, with the appreciation that in order to identify PHIL readings it is necessary “to hold to a strict chronological sequence of Philoxenus’ works.”5 Vööbus happily lighted upon a textual source that had “not undergone the possible changes and modifications which could be 1 The substance of this article was presented to a seminar convened by Dr Hidemi Takahashi at the University of Tokyo, 28 September 2006. -

Dr Sebastian P

Dr Sebastian P. Brock Position: Retired (formerly Reader in Syriac Studies; Professorial Fellow of Wolfson College) Faculty / College Address: Oriental Institute / Wolfson College Email: [email protected] Research Interests: Having started out with a primary research interest in the textual history of the Septuagint, the encounter with important unpublished texts in Syriac led me to turn for the most part to various areas of Syriac literature, in particular, translations from Greek and the history of translation technique, dialogue and narrative poems, hagiography, certain liturgical texts, and monastic literature. Current Projects: Editing various unpublished Syriac texts Greek words in Syriac Diachronic aspects of Syriac word formation Syriac dialogue poems Courses Taught: Lessons Recent publications: From Ephrem to Romanos: Interactions between Syriac and Greek in Late Antiquity (Aldershot: Variorum CSS 664, 1999). (with D.G.K.Taylor, E.Balicka-Witakowski, W.Witakowski), The Hidden Pearl. The Syrian Orthodox Church and its Ancient Aramaic Heritage. I, (with DGKT) The Ancient Aramaic Heritage; II, (with DGKT, EB-W, WW), The Heirs of the Ancient Aramaic Heritage; III (with WW), At the Turn of the Third Millennium: the Syrian Orthodox Witness (Rome: Trans World Film Italia, 2001). Fire from Heaven: Studies in Syriac Theology and Liturgy (Aldershot: Variorum SCSS 863, 2006). The Wisdom of Isaac of Nineveh [Syriac-English] (Piscataway NJ, 2006). (with G. Kiraz), Ephrem the Syrian. Select Poems [Syriac-English] (Eastern Christian Texts 2; Provo, 2006). (ed), reprint (with new vol. 6) of P. Bedjan, Homilies of Mar Jacob of Sarug, I- VI (Piscataway NJ, 2006). An Introduction to Syriac Studies (Piscataway NJ, 2006). -

Introduction and Index

Th e Practical Christology of Philoxenos of Mabbug DAVID A. MICHELSON Preview - Copyrighted Material 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © David A. Michelson 2014 Th e moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2014 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2014940446 ISBN 978–0–19–872296–0 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work. -

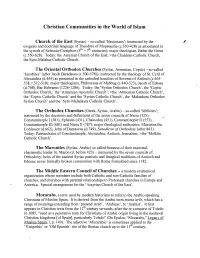

Christian Communities in the World of Islam

Christian Communities in the World of Islam Church of the East (Syriac) - so-called 'Nestorians'; instructed by the exegesis and doctrinal language of Theodore ofMopsuestia (c.350-428) as articulated in the synods of Seleucia-Ctesiphon (5 th > 7th centuries); major theologian, Babai the Great (c.550-628). Today: the Assyrian Church of the East; >the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church. The Oriental Orthodox Churches (Syriac, Armenian, Coptic) - so-called 'Jacobites' (after Jacob Baradaeus (c.500-578)); instructed by the theology of St. Cyril of Alexandria (d.444) as presented in the cathedral homilies of Severus of Antioch (c.465 538, r.512-518); major theologians, Philoxenus ofMabbug (c.440-523), Jacob ofEdessa (d.708), Bar Hebraeus (1226-1286). Today: the 'Syrian Orthodox Church', the ':Coptic Orthodox Church,' the 'Armenian Apostolic Church'; >the 'Armenian Catholic Church', the 'Coptic Catholic Church' and-the 'Syrian Catholic Church', the 'Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church' and the 'Syro-Malankara Catholic Church'. The Orthodox Churches (Greek, Syriac, Arabic) - so-called 'Melkites'; instructed by the decisions and definitions of the seven councils ofNicea (325), Constantinople I (381), Ephesus (431), Chalcedon (451), Constantinople II (553), Constantinople III (681) and Nicea II (787); major theological authorities, Maximus the Confessor (d.662), John of Damascus (d.749), Synodicon ofOrthodoxy (after 843). Today: Patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem; >the 'Melkite Catholic Church'. The Maronites (Syriac, Arabic) so called because of their ancestral, charismatic leader St. Maron (d. before 423) - instructed by the seven councils of Orthodoxy; heirs of the ancient Syriac patristic and liturgical traditions of Antioch and Edessa; never fomlally broken communion with Rome formalized since 1182. -

The Early Spread of Christianity in Central Asia and the Far East: a New Document

BR 1065 .M53 1925 Mingana, Alphonse, 1881- 1937. The early spread of Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from The Arcadia Fund https://archive.org/details/earlyspreadofchrOOming THE EARLY SPREAD OF CHRISTIANITY I IN CENTRAL ASIA AND THE FAR EAST: I A NEW DOCUMENT ALPHONSE 'MING AN A, D.D. ASSISTANT-KEEPER OF MANUSCRIPTS IN THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY, AND SPECIAL LECTURER IN ARABIC IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER Reprinted\ with Additions, from " The Bulletin of the John Rylands Library,” Vol. 9, No. 2, July, 1925 MANCHESTER: THE, UNIVERSITY PRESS, 23 LIME GROVE, OXFORD ROAD. LONGMANS, GREEN & CO., 39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON, E.C., NEW YORK, TORONTO, BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAS. MCMXXV. THE EARLY SPREAD OF CHRISTIANITY IN CENTRAL ASIA AND THE FAR EAST: A NEW DOCUMENT. By A. MINGANA, D.D. ASSISTANT KEEPER OF MANUSCRIPTS IN THE JOHN RYLANDS LIBRARY, AND SPECIAL LECTURER IN ARABIC IN THE UNI¬ VERSITY OF MANCHESTER. Foreword. I. BEFORE venturing into the subject of the evangelisation of the peoples of Mongolian race, it would be useful to examine the ethnological state of the powerful agglomeration of clans inhabiting the adjacent lands lying on the eastern and western banks of the river Oxus. There we meet with constant struggles for supremacy between two apparently different races, distinguished by the generic appellations of Iran and Turan. They were somewhat loosely separated by the historic river, the shallow waters of which in a summer month, or in a rainless season, proved always powerless to prevent the perpetual clash of arms between the warring tribes of the two rivals whose historic habitat lay on its eastern and western borders. -

Paths of Western Law After Justinian M

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 1-1-2006 Paths of Western Law After Justinian M. Stuart Madden Pace Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Recommended Citation Madden, M. Stuart, "Paths of Western Law After Justinian" (2006). Pace Law Faculty Publications. Paper 130. http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/130 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M. Stuart add en^ Preparation of the Code of Justinian, one part of a three-part presentation of Roman law published over the three-year period from 533 -535 A.D, had not been stymied by the occupation of Rome by the Rugians and the Ostrogoths. In most ways these occupations worked no material hardship on the empire, either militarily or civilly. The occupying Goths and their Roman counterparts developed symbiotic legal and social relationships, and in several instances, the new Germanic rulers sought and received approval of their rule both from the Western Empire, seated in Constantinople, and the Pope. Rugian Odoacer and Ostrogoth Theodoric each, in fact, claimed respect for Roman law, and the latter ruler held the Roman title patricius et magister rnilitum. In sum, the Rugians and the Ostrogoths were content to absorb much of Roman law, and to work only such modifications as were propitious in the light of centuries of Gothic customary law. -

Paths of Western Law After Justinian

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law January 2006 Paths of Western Law After Justinian M. Stuart Madden Pace Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Recommended Citation Madden, M. Stuart, "Paths of Western Law After Justinian" (2006). Pace Law Faculty Publications. 130. https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/130 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M. Stuart add en^ Preparation of the Code of Justinian, one part of a three-part presentation of Roman law published over the three-year period from 533 -535 A.D, had not been stymied by the occupation of Rome by the Rugians and the Ostrogoths. In most ways these occupations worked no material hardship on the empire, either militarily or civilly. The occupying Goths and their Roman counterparts developed symbiotic legal and social relationships, and in several instances, the new Germanic rulers sought and received approval of their rule both from the Western Empire, seated in Constantinople, and the Pope. Rugian Odoacer and Ostrogoth Theodoric each, in fact, claimed respect for Roman law, and the latter ruler held the Roman title patricius et magister rnilitum. In sum, the Rugians and the Ostrogoths were content to absorb much of Roman law, and to work only such modifications as were propitious in the light of centuries of Gothic customary law. -

Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Catholic Church St. Maron Feast

February 9, 2020 Bulletin #6 Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Catholic Church 2216 Eoff Street, Wheeling, WV 26003 Rectory: 304-233-1688 • Fax: 304-233-4714 E-Mail: [email protected] • Web Site: www.ololwv.com Msgr. Bakhos Chidiac, Pastor Mary Lee Porter, Organist St. Maron Feast Day Commemoration of the Righteous & Just *Weekend Masses: Saturday evening at 4:00 p.m. [Rosary & Litany start 20 minutes before Mass] Sunday morning at 10:30 a.m. [Rosary & Litany start 20 minutes before Mass] *Weekday Masses: Tuesday and Thursday at 12:05 p.m. [Rosary & Litany start 20 minutes before Mass] Monday, Wednesday, and Friday No Mass *Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament: First Saturday of the month at 3:30 p.m. First Sunday of the month after 10:30 a.m. Mass *Confession: Saturday: 3:00 p.m. to 3:45 p.m. or any other time by appointment *Baptism: Please call the Pastor as soon as baby is born; at least one Godparent must be Catholic *Weddings: Please make arrangements at least six months in advance before any other plans are made *Sick Calls & Anointing of the Sick: Please notify the Pastor at 304-233-1688 *Parish Council: Lou Khourey, Mike Linton, Rita Strawn, P.J. Lenz, Mary Stees *Choir Members: Earl Duffy, George Thomas, Lou Khourey, Robert Harris, Shelly Hancher, Ted Olinski, Natalie Horner *Bulletin Coordinator: Thomasina Geimer *Sacristan: Mike Linton *Altar Boys: Dalton Haas, Shaun Hancher, Christopher AlKhouri & Luke Lenz *Cedar Club: Linda Duffy, President *Women’s Society: Carol Dougherty, President *Bulletin Announcements: Submit all Bulletin Information to Msgr. -

Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation

Empire of Hope and Tragedy: Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Swain Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Timothy Gregory, Co-advisor Anthony Kaldellis Kristina Sessa, Co-advisor Copyright by Brian Swain 2014 Abstract This dissertation explores the intersection of political and ethnic conflict during the emperor Justinian’s wars of reconquest through the figure and texts of Jordanes, the earliest barbarian voice to survive antiquity. Jordanes was ethnically Gothic - and yet he also claimed a Roman identity. Writing from Constantinople in 551, he penned two Latin histories on the Gothic and Roman pasts respectively. Crucially, Jordanes wrote while Goths and Romans clashed in the imperial war to reclaim the Italian homeland that had been under Gothic rule since 493. That a Roman Goth wrote about Goths while Rome was at war with Goths is significant and has no analogue in the ancient record. I argue that it was precisely this conflict which prompted Jordanes’ historical inquiry. Jordanes, though, has long been considered a mere copyist, and seldom treated as an historian with ideas of his own. And the few scholars who have treated Jordanes as an original author have dampened the significance of his Gothicness by arguing that barbarian ethnicities were evanescent and subsumed by the gravity of a Roman political identity. They hold that Jordanes was simply a Roman who can tell us only about Roman things, and supported the Roman emperor in his war against the Goths.