Sri Lanka Print 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Un/Selfish Leader Changing Notions in a Tamil Nadu Village

The un/selfish leader Changing notions in a Tamil Nadu village Björn Alm The un/selfish leader Changing notions in a Tamil Nadu village Doctoral dissertation Department of Social Anthropology Stockholm University S 106 91 Stockholm Sweden © Björn Alm, 2006 Department for Religion and Culture Linköping University S 581 83 Linköping Sweden This book, or parts thereof, may be reproduced in any form without the permission of the author. ISBN 91-7155-239-1 Printed by Edita Sverige AB, Stockholm, 2006 Contents Preface iv Note on transliteration and names v Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Structure of the study 4 Not a village study 9 South Indian studies 9 Strength and weakness 11 Doing fieldwork in Tamil Nadu 13 Chapter 2 The village of Ekkaraiyur 19 The Dindigul valley 19 Ekkaraiyur and its neighbours 21 A multi-linguistic scene 25 A religious landscape 28 Aspects of caste 33 Caste territories and panchayats 35 A village caste system? 36 To be a villager 43 Chapter 3 Remodelled local relationships 48 Tanisamy’s model of local change 49 Mirasdars and the great houses 50 The tenants’ revolt 54 Why Brahmans and Kallars? 60 New forms of tenancy 67 New forms of agricultural labour 72 Land and leadership 84 Chapter 4 New modes of leadership 91 The parliamentary system 93 The panchayat system 94 Party affiliation of local leaders 95 i CONTENTS Party politics in Ekkaraiyur 96 The paradox of party politics 101 Conceptualising the state 105 The development state 108 The development block 110 Panchayats and the development block 111 Janus-faced leaders? 119 -

Socio-Religious Desegregation in an Immediate Postwar Town Jaffna, Sri Lanka

Carnets de géographes 2 | 2011 Espaces virtuels Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon Madavan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 DOI: 10.4000/cdg.2711 ISSN: 2107-7266 Publisher UMR 245 - CESSMA Electronic reference Delon Madavan, « Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town », Carnets de géographes [Online], 2 | 2011, Online since 02 March 2011, connection on 07 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/cdg/2711 ; DOI : 10.4000/cdg.2711 La revue Carnets de géographes est mise à disposition selon les termes de la Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Socio-religious desegregation in an immediate postwar town Jaffna, Sri Lanka Delon MADAVAN PhD candidate and Junior Lecturer in Geography Université Paris-IV Sorbonne Laboratoire Espaces, Nature et Culture (UMR 8185) [email protected] Abstract The cease-fire agreement of 2002 between the Sri Lankan state and the separatist movement of Liberalisation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), was an opportunity to analyze the role of war and then of the cessation of fighting as a potential process of transformation of the segregation at Jaffna in the context of immediate post-war period. Indeed, the armed conflict (1987-2001), with the abolition of the caste system by the LTTE and repeated displacements of people, has been a breakdown for Jaffnese society. The weight of the hierarchical castes system and the one of religious communities, which partially determine the town's prewar population distribution, the choice of spouse, social networks of individuals, values and taboos of society, have been questioned as a result of the conflict. -

Migration and Morality Amongst Sri Lankan Catholics

UNLIKELY COSMPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Bernardo Enrique Brown August, 2013 © 2013 Bernardo Enrique Brown ii UNLIKELY COSMOPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS Bernardo Enrique Brown, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2013 Sri Lankan Catholic families that successfully migrated to Italy encountered multiple challenges upon their return. Although most of these families set off pursuing very specific material objectives through transnational migration, the difficulties generated by return migration forced them to devise new and creative arguments to justify their continued stay away from home. This ethnography traces the migratory trajectories of Catholic families from the area of Negombo and suggests that – due to particular religious, historic and geographic circumstances– the community was able to develop a cosmopolitan attitude towards the foreign that allowed many of its members to imagine themselves as ―better fit‖ for migration than other Sri Lankans. But this cosmopolitanism was not boundless, it was circumscribed by specific ethical values that were constitutive of the identity of this community. For all the cosmopolitan curiosity that inspired people to leave, there was a clear limit to what values and practices could be negotiated without incurring serious moral transgressions. My dissertation traces the way in which these iii transnational families took decisions, constantly navigating between the extremes of a flexible, rootless cosmopolitanism and a rigid definition of identity demarcated by local attachments. Through fieldwork conducted between January and December of 2010 in the predominantly Catholic region of Negombo, I examine the work that transnational migrants did to become moral beings in a time of globalization, individualism and intense consumerism. -

Musical Knowledge and the Vernacular Past in Post-War Sri Lanka

Musical Knowledge and the Vernacular Past in Post-War Sri Lanka Jim Sykes King’s College London “South Asian kings are clearly interested in vernacular culture zones has rendered certain vernacular Sinhala places, but it is the poet who creates them.” and Tamil culture producers in a subordinate fashion to Sinhala and Tamil ‘heartlands’ deemed to reside Sheldon Pollock (1998: 60) elsewhere, making it difficult to recognise histories of musical relations between Sinhala and Tamil vernac - This article registers two types of musical past in Sri ular traditions. Lanka that constitute vital problems for the ethnog - The Sinhala Buddhist heartland is said to be the raphy and historiography of the island today. The first city and region of Kandy (located in the central ‘up is the persistence of vernacular music histories, which country’); the Tamil Hindu heartland is said to be demarcate Sri Lankan identities according to regional Jaffna (in the far north). In this schemata, the south - cultural differences. 1 The second type of musical past ern ‘low country’ Sinhala musicians are treated as is a nostalgia for a time before the island’s civil war lesser versions of their up country Sinhala cousins, (1983-2009) when several domains of musical prac - while eastern Tamil musicians are viewed as lesser ver - tice were multiethnic. Such communal-musical inter - sions of their northern Tamil cousins. Meanwhile, the actions continue to this day, but in attenuated form southeast is considered a kind of buffer zone between (I have space here only to discuss the vernacular past, Tamil and Sinhala cultures, such that Sinhalas in the but as we will see, both domains overlap). -

Documents in Support of Their Respective Positions

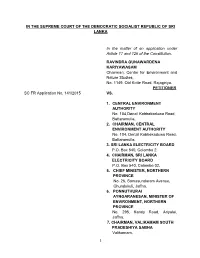

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application under Article 17 and 126 of the Constitution. RAVINDRA GUNAWARDENA KARIYAWASAM Chairman, Centre for Environment and Nature Studies, No. 1149, Old Kotte Road, Rajagiriya. PETITIONER SC FR Application No. 141/2015 VS. 1. CENTRAL ENVIRONMENT AUTHORITY No. 104,Denzil Kobbekaduwa Road, Battaramulla. 2. CHAIRMAN, CENTRAL ENVIRONMENT AUTHORITY No. 104, Denzil Kobbekaduwa Road, Battaramulla. 3. SRI LANKA ELECTRICITY BOARD P.O. Box 540, Colombo 2. 4. CHAIRMAN, SRI LANKA ELECTRICITY BOARD P.O. Box 540, Colombo 02. 5. CHIEF MINISTER, NORTHERN PROVINCE No. 26, Somasundaram Avenue, Chundukuli, Jaffna. 6. PONNUTHURAI AYNGARANESAN, MINISTER OF ENVIRONMENT, NORTHERN PROVINCE No. 295, Kandy Road, Ariyalai, Jaffna. 7. CHAIRMAN, VALIKAMAM SOUTH PRADESHIYA SABHA Valikamam. 1 8. NORTHERN POWER COMPANY (PVT) LTD. No. 29, Castle Street, Colombo 10. 9. HON. ATTORNEY GENERAL Attorney General‟s Department, Colombo 12. 10. BOARD OF INVESTMENT OF SRI LANKA Level 26, West Tower, World Trade Center, Colombo 1. 11. NATIONAL WATER SUPPLY AND DRAINAGE BOARD P.O. Box 14, Galle Road, Mt. Lavinia. RESPONDENTS 1. DR. RAJALINGAM SIVASANGAR Chunnakam East, Chunnakam. 2. SINNATHURAI SIVAMAINTHAN Chunnakam East, Chunnakam. 3. SIVASAKTHIVEL SIVARATHEES Chunnakam East, Chunnakam. ADDED RESPONDENTS BEFORE: Priyantha Jayawardena, PC, J. Prasanna Jayawardena, PC, J. L.T.B. Dehideniya, J. COUNSEL: Nuwan Bopage with Chathura Weththasinghe for the Petitioner. Dr. Avanti Perera, SSC for the 1st to 4th, 9th, 10th and 11th Respondents. Dr. K.Kanag-Isvaran,PC with L.Jeyakumar instructed by M/S Sinnadurai Sundaralingam and Balendra for the 5th Respondent. Dinal Phillips,PC with Nalin Dissanayake and Pulasthi Hewamanne instructed by Ms. -

Community List

ANNEXURE - III LIST OF COMMUNITIES I. SCHEDULED TRIB ES II. SCHEDULED CASTES Code Code No. No. 1 Adiyan 2 Adi Dravida 2 Aranadan 3 Adi Karnataka 3 Eravallan 4 Ajila 4 Irular 6 Ayyanavar (in Kanyakumari District and 5 Kadar Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 6 Kammara (excluding Kanyakumari District and 7 Baira Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 8 Bakuda 7 Kanikaran, Kanikkar (in Kanyakumari District 9 Bandi and Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Bellara 8 Kaniyan, Kanyan 11 Bharatar (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 9 Kattunayakan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 10 Kochu Velan 13 Chalavadi 11 Konda Kapus 14 Chamar, Muchi 12 Kondareddis 15 Chandala 13 Koraga 16 Cheruman 14 Kota (excluding Kanyakumari District and 17 Devendrakulathan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 18 Dom, Dombara, Paidi, Pano 15 Kudiya, Melakudi 19 Domban 16 Kurichchan 20 Godagali 17 Kurumbas (in the Nilgiris District) 21 Godda 18 Kurumans 22 Gosangi 19 Maha Malasar 23 Holeya 20 Malai Arayan 24 Jaggali 21 Malai Pandaram 25 Jambuvulu 22 Malai Vedan 26 Kadaiyan 23 Malakkuravan 27 Kakkalan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 24 Malasar Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 25 Malayali (in Dharmapuri, North Arcot, 28 Kalladi Pudukkottai, Salem, South Arcot and 29 Kanakkan, Padanna (in the Nilgiris District) Tiruchirapalli Districts) 30 Karimpalan 26 Malayakandi 31 Kavara (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 27 Mannan Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 28 Mudugar, Muduvan 32 Koliyan 29 Muthuvan 33 Koosa 30 Pallayan 34 Kootan, Koodan (in Kanyakumari District and 31 Palliyan Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 32 Palliyar 35 Kudumban 33 Paniyan 36 Kuravan, Sidhanar 34 Sholaga 39 Maila 35 Toda (excluding Kanyakumari District and 40 Mala Shenkottah Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 41 Mannan (in Kanyakumari District and Shenkottah 36 Uraly Taluk of Tirunelveli District) 42 Mavilan 43 Moger 44 Mundala 45 Nalakeyava Code III (A). -

Sri Lankan Deportees Allegedly Tortured on Return from the UK and Other Countries All Cases Have Supporting Medical Documentation

Sri Lankan deportees allegedly tortured on return from the UK and other countries All cases have supporting medical documentation I. Cases in which asylum was previously denied in the UK Case 1 PK, a 32-year-old Tamil man from Jaffna, was among 24 Tamils deported to Sri Lanka by the UK Border Agency on 16 June 2011. PK told Human Rights Watch he had been previously arrested by the Sri Lankan police and remanded in custody by the Colombo Magistrate court. While in detention he was seen by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) on three occasions. PK had fled Sri Lanka in 2004 following the split of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) with its Eastern Commander, Colonel Karuna, and sought asylum in the UK in April 2005. PK told Human Rights Watch that he and the other deportees were taken aside for questioning by officials who introduced themselves as CID (Criminal Investigation Department) soon after they arrived at Katunayake International Airport in Negombo, outside of Colombo. PK said the officials took all his details down and allowed him to leave the airport. PK said: My aunt warned me not to go to Jaffna through Vanni as I did not have my national ID card. I stayed in Negombo with her. While I was in Negambo, the authorities went to my address in Jaffna, looking for me. However after about six months, I decided to go to Jaffna. On 10 December 2011 on my way, I was stopped at the Omanthai checkpoint [along the north-south A9 highway] by the authorities. -

21St October 1966 Uprising Merging the North and East Water and Big Business

December 2006 21st October 1966 Uprising SK Senthivel Merging the North and East E Thambiah Water and Big Business Krishna Iyer; India Resource Centre Poetry: Mahakavi, So Pa, Sivasegaram ¨ From the Editor’s Desk ¨ NDP Diary ¨ Readers’ Views ¨ Sri Lankan Events ¨ International Events ¨ Book Reviews The Moon and the Chariot by Mahaakavi "The village has gathered to draw the chariot, let us go and hold the rope" -one came forward. A son, borne by mother earth in her womb to live a full hundred years. Might in his arms and shoulders light in his eyes, and in his heart desire for upliftment amid sorrow. He came. He was young. Yes, a man. The brother of the one who only the day before with agility of mind as wings on his shoulder climbed the sky, to touch the moon and return -a hard worker. He came to draw the rope with a wish in his heart: "Today we shall all be of one mind". "Halt" said one. "Stop" said another. "A weed" said one. "Of low birth" said another. "Say" said one. "Set alight" said another. The fall of a stone, the slitting of a throat, the flight of a lip and teeth that scattered, the splattering of blood, and an earth that turned red. A fight there was, and people were killed. A chariot for the village to draw stood still like it struck root. On it, the mother goddess, the creator of all worlds, sat still, dumbfounded by the zealotry of her children. Out there, the kin of the man who only the day before had touched the moon is rolling in dirt. -

Nationalism, Caste-Blindness, and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-War Jaffna Society

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 51–70 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.145 Nationalism, Caste-Blindness, and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-War Jaffna Society Kalinga Tudor Silva1 Abstract More than a decade after the end of the 26-year old LTTE—led civil war in Sri Lanka, a particular section of the Jaffna society continues to stay as Internally Displaced People (IDP). This paper tries to unravel why some low caste groups have failed to end their displacement and move out of the camps while everybody else has moved on to become a settled population regardless of the limitations they experience in the post-war era. Using both quantitative and qualitative data from the affected communities the paper argues that ethnic-biases and ‘caste-blindness’ of state policies, as well as Sinhala and Tamil politicians largely informed by rival nationalist perspectives are among the underlying causes of the prolonged IDP problem in the Jaffna Peninsula. In search of an appropriate solution to the intractable IDP problem, the author calls for an increased participation of these subaltern caste groups in political decision making and policy dialogues, release of land in high security zones for the affected IDPs wherever possible, and provision of adequate incentives for remaining people to move to alternative locations arranged by the state in consultation with IDPs themselves and members of neighbouring communities where they cannot be relocated at their original sites. Keywords Caste, caste-blindness, ethnicity, nationalism, social class, IDPs, Panchamars, Sri Lanka 1Department of Sociology, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka E-mail: [email protected] © 2020 Kalinga Tudor Silva. -

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka Report

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka A multi-agency approach coordinated by Central Environment Authority and Disaster Management Centre, Supported by United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Environment Programme Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka November 2014 A Multi-agency approach coordinated by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) of the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy and Disaster Management Centre (DMC) of the Ministry of Disaster Management, supported by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Integrated Strategic Environment Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka ISBN number: 978-955-9012-55-9 First edition: November 2014 © Editors: Dr. Ananda Mallawatantri Prof. Buddhi Marambe Dr. Connor Skehan Published by: Central Environment Authority 104, Parisara Piyasa, Battaramulla Sri Lanka Disaster Management Centre No 2, Vidya Mawatha, Colombo 7 Sri Lanka Related publication: Map Atlas: ISEA-North ii Message from the Hon. Minister of Environment and Renewable Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is a systematic decision support process, aiming to ensure that due consideration is given to environmental and other sustainability aspects during the development of plans, policies and programmes. SEA is widely used in many countries as an aid to strategic decision making. In May 2006, the Cabinet of Ministers approved a Cabinet of Memorandum -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

Prospects and Problems in Sri Lankan Studies

1 Prospects and Problems in Sri Lankan Studies John D. Rogers - November 1999, revised June 2005. This essay is intended to provide an introduction to recent Sri Lankan studies in the United States. The first section outlines the broad parameters of the field, and the second places American-based scholarship in the context of global scholarship on Sri Lanka, especially that being carried out in Sri Lanka itself. The third section discusses the prospects for American research on Sri Lanka. The essay is not intended to serve as a comprehensive review of current scholarship in the United States, but enough references are provided to give some guidance to scholars or graduate students considering entering the field. It covers only recent scholarship, although some older works remain important (e.g., Ryan 1953, Wriggins 1960, Kearney 1971, G. Obeyesekere 1981). American Scholarship on Sri Lanka The number of American-based scholars and advanced graduate students who focus on Sri Lanka is quite small. At any one time close to 100 individuals fall into this category, including those scholars for whom the Sri Lanka aspect of their research is very much secondary to disciplinary or thematic interests. But enough people are active in the field to constitute a lively intellectual community. Most American-based scholars with doctorates received their degrees from American institutions, but a few have overseas graduate degrees, principally from British universities. They are found in all types of American higher education institutions, from large research universities to small colleges that focus on teaching undergraduates. Independent scholars also contribute to the field.