From the Wilkinson's Rules to the Pathalgadi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHINESE ROCKET LONG MARCH 5 (Science) the Shijian 20 Satellite

CHINESE ROCKET LONG MARCH 5 (Science) China's biggest rocket, the Long March 5, returned to flight for the first time since a 2017 failure Friday (Dec. 27) in a dazzling nighttime launch for the Chinese space program. The Long March 5 Y3 rocket lifted off at 8:45 p.m. Beijing Time carrying the experimental Shijian 20 communications satellite into a geosynchronous orbit. The satellite, which weighs a reported 8 metric tons, is China's heaviest and most advanced satellite to date, according to state media reports. The successful launch is the first Long March 5 since a first-stage booster failure in 2017 destroyed the Shijian 18 satellite. The failure prompted redesigns in the rocket's first-stage engines, which led to a two-year gap between missions. The first Long March 5 rocket lifted off in 2016. The Long March 5 is an essential booster for China's space ambitions. The heavy-lift booster will be the one to launch China's space station modules into orbit, as well as a Mars lander in 2020 and the Chang'e 5 moon sample-return mission. China is also expected to use a version of the Long March 5, called the Long March 5B, to launch a new crewed spacecraft — the successor to its current Shenzhou crew capsule. The rocket stands 184 feet (56 meters) tall and weighs nearly 2 million lbs. (867,000 kilograms) at liftoff. It is capable of carrying payloads of up to 55,000 lbs. (25,000 kilograms) into low Earth orbit. It can haul up 31,000 lbs. -

4YZ R Gzcfd Devad Fa Reert\ Eczxxvcd TYR`D

4! *+ # %(,"-$ ","-$- !" .-,6,.6 7.'5$% *10630+$ #% 4" ) 9 + 7 ++6 48 9 7))! ##)) # 8) 56 7 # 757) )#+ + 8 # + 6) + 57+ # ++ #5 8 5 9 7 :;9 . /0 12 . ) $$% #$%&& #"$'('() *!+ CM Canteen scheme in rural areas, free technical education tate Finance Minister for girl students, modernisation SRameshwar Oraon present- of district schools etc. ed the first Budget of Grand After the Budget presenta- Alliance (Congress, JMM and tion in the Assembly, Chief RJD) Government in the State Minister Hemant Soren termed in the tune of 86,370 core for the budget as a revolutionary he Grand Alliance Financial Year 2020-21 focus- one because it focuses n poor, TGovernment headed by ing mainly on rural develop- farmers and the unemployed Chief Minister Hemant Soren ment, agriculture and allied youth of the State. “We have on Tuesday presented its sectors, education, health, wel- turned the chariot of gover- 86,370 Budget. Chief Minister fare, drinking water and sani- nance towards the huts of the in his Budget had tried to tation among others. poor. The Government has pri- address all section of societies The Budget makes provision oritised that no poor remains such as farm loan waiver of up of 25,047.43 crore for general hungry, no child of a poor man to 50,000 and 100-unit free sector, 32,167.58 crore for social rear gaots, no child is devoid of power besides stating that all sector and 29,154 crore for education, every person of the residents will be covered under financial sector. In the fiscal State has a house of his own and medical treatment for all up to year 2020-21, the State will get clothes on his body,” he said. -

Detailed Result

DETAILED RESULT AC NO. & Name - 1 Rajmahal SL NO. Names of the Contesting Candidates Sex Age Category Party Votes from EVM Postal Votes Total Votes 1 ARUN MANDAL M 55 GEN BJP 51277 0 51277 2 MD. TAJUDDIN M 36 GEN JMM 40874 0 40874 3 THOMAS HANSDA M 58 ST INC 14782 0 14782 4 NAZRUL ISLAM M 48 GEN AITC 7017 0 7017 5 MD. MOINUDDIN SHEKH M 43 GEN CPM 6065 0 6065 6 DHRUV BHAGAT M 58 GEN LJP 3811 0 3811 7 BINOD KUMAR YADAV M 31 GEN IND 3224 0 3224 8 MUKHTAR HUSSAIN M 48 GEN RSP 2568 0 2568 9 VIBHASH KUMAR SHAH M 29 GEN AJSU 2030 0 2030 10 IDRISH M 40 GEN BSP 1800 0 1800 11 ABHIMANYU MANDAL M 38 GEN SHS 1434 0 1434 12 DHARMENDRA KUMAR SINGH M 28 GEN IND 1236 0 1236 Grand Total : 136118 0 136118 Office of the Chief Electoral Officer, Jharkhand 1 General Election to Jharkhand Legislative Assembly 2009 DETAILED RESULT AC NO. & Name - 2 Borio-(ST) SL NO. Names of the Contesting Candidates Sex Age Category Party Votes from EVM Postal Votes Total Votes 1 LOBIN HEMBRAM M 54 ST JMM 37586 0 37586 2 TALA MARANDI M 46 ST BJP 28546 0 28546 3 SURYA NRAYAN HANSDA M 30 ST JVM 25835 0 25835 4 RAMA PAHARIA M 34 ST IND 3723 0 3723 5 SUNITA HANSDA F 28 ST IND 3114 0 3114 6 PRABHAWATI BASKEY F 36 ST CPM 3111 0 3111 7 RAMKRISHNA SOREN M 38 ST IND 2109 0 2109 8 PAULUS MURMU M 32 ST AJSU 1944 0 1944 9 RODRICK HEMBROM M 43 ST IND 1337 0 1337 10 MAHESH MALTO M 41 ST RSP 1276 0 1276 11 KHALIFA KISKU M 59 ST IND 1212 0 1212 12 RAPAZ CHANDA KISKU M 65 ST IND 1140 0 1140 13 RAYMOND MURMU M 31 ST BSP 1069 0 1069 14 MANDAKINI MURMU F 44 ST LJP 995 0 995 15 MANOJ KUMAR GOND M 32 ST IND 976 0 976 Grand Total : 113973 0 113973 Office of the Chief Electoral Officer, Jharkhand 2 General Election to Jharkhand Legislative Assembly 2009 DETAILED RESULT AC NO. -

Mr. Pranab Mukherjee Mohammad Hamid Ansari Manmohan Singh Ms

Name Mr. Pranab Mukherjee Mohammad Hamid Ansari Manmohan Singh Ms. Meira Kumar Mr. P. J. Kurien Mr. Karia Munda Ms. Sushma Swaraj Mr. Arun Jaitley Dr. Montek Singh Ahluwalia Mr. V. S. Sampath Mr. Hari Shankar Brahma Justice K.G. Balakrishnan Mr. Shashi Kant Sharma Mr. Justice M.N. Rao Prof. D.P. Agarwal Dr. M.S. Swaminathan Mr. Satyanand Mishra Mr. N. K. Raghupathy Dr. Vishwa Mohan Katoch Mr. C. Chandramouli Mr. Justice D. K. Jain Mr. Duvvuri Subbarao Mr. Baldev Raj Mr. Shailesh Gupta Dr. (Ms.) Poonam Kishore Saxena Mr. U. K. Sinha Ms. Mamata Sharma Dr. Vijay Kelkar Mr. Sam Pitroda Shri Jawhar Sircar Mr. Ratan Tata Mr. Krishnakumar Natarajan Mr. Rajkumar Dhoot Mr. Shiv Shankar Menon Mr. Shumsher K. Sheriff Mr. T. K. Vishwanathan Syed Asif Ibrahim Mr. Ranjit Sinha Mr. Alok Joshi Mr. Arvind Ranjan Mr. Pranay Sahay Mr. Rajiv Mr. P. K. Mehta Shri Ajay Chadha Prof. Ved Prakash Dr. V. K. Saraswat Dr. R. Chidambaram Dr. K. Radhakrishnan Dr. R. K. Sinha Mr. Wajahat Habibullah Dr. Pronob Sen Shri Arun Chaudhary Mr. Rameshwar Oraon Mr. P. L. Punia Mr. S. C. Sinha Vice Admiral Anurag G Thapliyal Mr. N. Srinivasan Dr. Syed Nasim Ahmad Zaidi Justice Altamas Kabir Mr. Mohan Parasaran Mr. K. K. Chakravarty Mr. S. Gopalkrishnan General Vikram Singh Admiral Devendra Kumar Joshi Air Chief Marshal Norman Anil Kumar Browne Mr. Goolam E. Vahanvati Mrs. Kushal Singh Dr. Y. V. Reddy Mr. Subhash Joshi Smt. Mrinal Pande Designation President of India Vice President Prime Minister of India (Chairman of Planing Commission) Speaker, Lok Sabha Deputy Chairman, Rajya -

Report Good Governance for Tribal Development and Administration May 2012

NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR SCHEDULED TRIBES SPECIAL REPORT GOOD GOVERNANCE FOR TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT AND ADMINISTRATION MAY 2012 CONTENTS Page. No. LETTER TO PRESIDENT I-II CHAPTERS 1 GOOD GOVERNANCE IN SCHEDULED AND TRIBAL AREAS 1-32 INTRODUCTION 1 GOVERNANCE OF SCHEDULED AREAS: HISTORICAL 1 BACKGROUND A. THE SCHEDULED DISTRICTS ACT 1874 1 B. GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT, 1919 2 C. GOVERNMENT OF INDIA ACT, 1935 2 D. DRAFT CONSTITUTION DISCUSSED IN THE 3 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY E. SPECIAL SAFEGUARDS FOR SCHEDULED TRIBES AND 4 SCHEDULED AREAS PRESENT DEFINITION OF SCHEDULED AREAS 5 SCHEDULED AREA1 AND PROCEDURE FOR SCHEDULING, 6 RESCHEDULING AND ALTERATION OF SCHEDULED AREAS TRIBAL AREAS UNDER SIXTH SCHEDULE 8 CURRENT PERSPECTIVE 8 ILO CONVENTIONS CONCERNING TRIBAL PEOPLE 8 (a) COMMENTS OF MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS 9 (b) COMMENTS OF MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS 10 (c) COMMENTS OF MINISTRY OF TRIBAL AFFAIRS 11 VIEWS EXPRESSED BY THE PRESIDENT REGARDING ROLE OF 13 THE GOVERNORS IN THE CONFERENCE OF GOVERNORS OF THE STATES HELD IN SEPTEMBER, 2008 PRESENTATION BY GOVERNORS OF THE STATES IN THE 15 CONFERENCE VIEWS OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF INDIA ON THE ROLE 19 AND POWERS OF GOVERNOR GENERAL OBSERVATIONS 20 EXECUTIVE AND DISCRETIONARY POWERS OF THE 20 GOVERNOR CONCLUDING OPINION OF ATTORNEY GENERAL OF 20 INDIA 3RD REPORT TITLED "STANDARDS OF ADMINISTRATION AND 21 GOVERNANCE IN THE SCHEDULED AREAS" BY THE STANDING COMMITTEE ON INTER-SECTORAL ISSUES RELATING TO TRIBAL DEVELOPMENT. COMMENTS OF THE NATIONAL COMMISSION FOR SCHEDULED 21 TRIBES ON THE OBSERVATION -

ANSWERED ON:19.08.2004 PENDING RAILWAY PROJECTS in JHARKHAND Dubey Shri Chandra Shekhar;Mahto Shri Tek Lal;Murmu Shri Hemlal;Oraon Dr

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA RAILWAYS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:3286 ANSWERED ON:19.08.2004 PENDING RAILWAY PROJECTS IN JHARKHAND Dubey Shri Chandra Shekhar;Mahto Shri Tek Lal;Murmu Shri Hemlal;Oraon Dr. Rameshwar Will the Minister of RAILWAYS be pleased to state: (a) whether the projects relating to the railways in Jharkhand State are lying pending; (b) if so, the present status of pending/ongoing rail projects and surveys in the above State, project-wise; (c) target set for completion of each of these projects and surveys; (d) the amount spent and likely to be spent on these projects; and (e) the steps initiated by the Government to complete the aforesaid projects within the stipulated time? Answer MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS ( SHRI R.VELU ) (a) to (e): A statement is attached. STATEMENT REFERRED TO IN REPLY TO PARTS (a) to (e) O F UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 3286 BY SHRI TEK LAL MAHATO, DR.RAMESHWAR ORAON, SHRI HEMLAL MURMU AND SHRI CHANDRA SEKHAR DUBEY TO BE ANSWERED IN LOK SABHA ON 19.08.2004 REGARDING PENDING RAILWAY PROJECTS IN JHARKHAND. (a) to (e): The pending projects are considered as those projects, which had been included in the Budget with the proviso that the work would be taken up after obtaining necessary clearances. No such project is pending in the State of Jharkhand. The status of various ongoing projects falling fully or partly in Jharkhand, their anticipated cost and outlay for 2004-05, expenditure incurred upto 31.3.2004 and the target date of completion, wherever fixed are given as under:- S.No. -

Alphabetical List of Recommendations Received for Padma Awards - 2014

Alphabetical List of recommendations received for Padma Awards - 2014 Sl. No. Name Recommending Authority 1. Shri Manoj Tibrewal Aakash Shri Sriprakash Jaiswal, Minister of Coal, Govt. of India. 2. Dr. (Smt.) Durga Pathak Aarti 1.Dr. Raman Singh, Chief Minister, Govt. of Chhattisgarh. 2.Shri Madhusudan Yadav, MP, Lok Sabha. 3.Shri Motilal Vora, MP, Rajya Sabha. 4.Shri Nand Kumar Saay, MP, Rajya Sabha. 5.Shri Nirmal Kumar Richhariya, Raipur, Chhattisgarh. 6.Shri N.K. Richarya, Chhattisgarh. 3. Dr. Naheed Abidi Dr. Karan Singh, MP, Rajya Sabha & Padma Vibhushan awardee. 4. Dr. Thomas Abraham Shri Inder Singh, Chairman, Global Organization of People Indian Origin, USA. 5. Dr. Yash Pal Abrol Prof. M.S. Swaminathan, Padma Vibhushan awardee. 6. Shri S.K. Acharigi Self 7. Dr. Subrat Kumar Acharya Padma Award Committee. 8. Shri Achintya Kumar Acharya Self 9. Dr. Hariram Acharya Government of Rajasthan. 10. Guru Shashadhar Acharya Ministry of Culture, Govt. of India. 11. Shri Somnath Adhikary Self 12. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao Shri Ganta Srinivasa Rao, Minister for Infrastructure & Investments, Ports, Airporst & Natural Gas, Govt. of Andhra Pradesh. 13. Prof. S.H. Advani Dr. S.K. Rana, Consultant Cardiologist & Physician, Kolkata. 14. Shri Vikas Agarwal Self 15. Prof. Amar Agarwal Shri M. Anandan, MP, Lok Sabha. 16. Shri Apoorv Agarwal 1.Shri Praveen Singh Aron, MP, Lok Sabha. 2.Dr. Arun Kumar Saxena, MLA, Uttar Pradesh. 17. Shri Uttam Prakash Agarwal Dr. Deepak K. Tempe, Dean, Maulana Azad Medical College. 18. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 1.Dr. Ashok Kumar Walia, Minister of Health & Family Welfare, Higher Education & TTE, Skill Mission/Labour, Irrigation & Floods Control, Govt. -

PARFORE Founding Members

http://www.parfore.in/ PARFORE Founding Members S.No Coordinates Photo Constituency Shri Suresh Prabhakar Prabhu Minister BJP (Haryana) 1 Ministry of Railways Rail Bhawan B-21, Sadhana, 16th New Delhi-110001 Road, Khar, Mumbai - 400 052 Phone: +91-11- 23387333 , (Maharashtra) Faxe:011 - 23010478 Tel. (022) 26496040 http://sureshprabhu.in/ [email protected] Fax : (022) 26485338 12, Akbar Road, New Delhi-110011 Phone: Res. 23010476 2 Shri Dinesh Trivedi Member of Parliament AITC (West Bengal) Lok Sabha 4, Lodhi Estate 8-A, Vivek Vihar, 13/3 New Delhi-110 003 (Ballygunge Circular Tel : (011) 24641124, Fax : 24647323 Road), Kolkata 700019 Cell: Mobile 09830050499 Tel. - {033} 24758503, Email: [email protected] Mobile 09830050499 www.dineshtrivedi.in 3 Shri Yashwant Sinha Former member of Parliament BJP Rajya Sabha Jharkhand HOUSA NO 228 SECTOR 15A, Noida, Uttar Pradesh Vill. Hupad, PO Morangi, Cell: 9868181937, 09013180414 Distt. Hazaribagh, Jharkhand Email: [email protected] www.yashwantsinha.in Tel. - {06546} 222998 4 Shri Madusudan Devram Mistry MP,Rajya Sabha & INC, Gujrat General Secretary Al l India Congress Committee (AICC) Plot No. 814, Sector – 8, AB-89, Shahjahan Road, Opp. Church, New Delhi -110001 Gandhinagar, Gujarat Tel. (O) : 23019080, 23010366 382008 Tel. (R) : 23013403, Tel. (079) 25625088 Cell:9868180068, 9013181033,9013181032 www.madhusudanmistry 5 Shri N.N. Krishnadas Former MP Lok Sabha & President, SWARALAYA "The Nest", College Road, The Nest,College Road, Palakkad - Kerala. Palghat - 678 001 Tel : 0491 2501011, Mob : 09744444808, (Kerala) Email: [email protected] Tel. (0491) 2500001 http://www.swaralayapalakkad.com/contact- us.html PARFORE Current Members (Rajya Sabha) http://rajyasabha.nic.in S.No Coordinates Photo Constituency Shri Naresh Gujral, MP, Rajya Sabha, SAD 1 5, Amrita Shergil Marg, Punjab Lodhi Road, New Delhi 110003 Phones: 24622772,24693999, 9868181823,9868181999, 9810017206 09478402210 Email: [email protected] Shri V.P.Singh Badnore MP, Rajya Sabha BJP ( Rajasthan) 2 Bungalow no. -

11.04 Hrs LIST of MEMBERS ELECTED to LOK SABHA Sl. No

Title: A list of Members elected to 14th Lok Sabha was laid on the Table of the House. 11.04 hrs LIST OF MEMBERS ELECTED TO LOK SABHA MR. SPEAKER: Now I would request the Secretary-General to lay on the Table a list (Hindi and English versions), containing the names of the Members elected to the Fourteenth Lok Sabha at the General Elections of 2004, submitted to the Speaker by the Election Commission of India. SECRETARY-GENERAL: Sir, I beg to lay on the Table a List* (Hindi and English versions), containing the names of Members elected to the Fourteenth Lok Sabha at the General Elections of 2004, submitted to the Speaker by the Election Commission of India. List of Members Elected to the 14th Lok Sabha. * Also placed in the Library. See No. L.T. /2004 SCHEDULE Sl. No. and Name of Name of the Party Affiliation Parliamentary Constituency Elected Member (if any) 1. ANDHRA PRADESH 1. SRIKAKULAM YERRANNAIDU KINJARAPUR TELUGU DESAM 2. PARVATHIPURAM(ST) KISHORE CHANDRA INDIAN NATIONAL SURYANARAYANA DEO CONGRESS VYRICHERLA 3. BOBBILI KONDAPALLIPYDITHALLI TELEGU DESAM NAIDU 4. VISAKHAPATNAM JANARDHANA REDDY INDIAN NATIONAL NEDURUMALLI CONGRESS 5. BHADRACHALAM(ST) MIDIYAM BABU RAO COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST) 6. ANAKAPALLI CHALAPATHIRAO PAPPALA TELUGU DESAM 7. KAKINADA MALLIPUDI MANGAPATI INDIAN NATIONAL PALLAM RAJU CONGRESS 8. RAJAHMUNDRY ARUNA KUMAR VUNDAVALLI INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 9. AMALAPURAM (SC) G.V. HARSHA KUMAR INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 10. NARASAPUR CHEGONDI VENKATA INDIAN NATIONAL HARIRAMA JOGAIAH CONGRESS 11. ELURU KAVURU SAMBA SIVA RAO INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 12. MACHILIPATNAM BADIGA RAMAKRISHNA INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 13. VIJYAWADA RAJAGOPAL GAGADAPATI INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 14. -

![Cfcr] Uvgv]`A^V E Vuftrez` Xve ]Z` ¶D Dyrcv](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5432/cfcr-uvgv-a-v-e-vuftrez-xve-z-%C2%B6d-dyrcv-5435432.webp)

Cfcr] Uvgv]`A^V E Vuftrez` Xve ]Z` ¶D Dyrcv

1 !"#$ %&'"!"#$ 234+42+5 0267 -32/% -%# /" ,,2 9, , 1 , 6 01 1 , 1/ ,2 02 78 2 1 21 / ,2 3 453 ( & & )* +) ( ,-' & $$ ! " # !$%$& $' R ! ""# $ tate Finance Minister SRameshwar Oraon present- ed the second Budget of Grand Alliance (Congress, JMM and RJD) Government in the State in the tune of 91,277 crore for Financial Year 2021-22, focusing primarily on educa- tion, rural development, agri- culture and allied sectors, health, welfare and social wel- fare, among others. The Budget makes provision of 75,755.01 crore for revenue expenditure and 15,521.99 crore for capital expenditure. For Financial Year 2021-22 37,943.34 crore have been allo- cated for establishment expen- diture, 37,008.09 crore for State schemes (including State’s part), 2,081.34 for Central Sector schemes and 12,244.23 crore for ! Centrally Sponsored Schemes (Centre’s part). ! " # $ # actions and it will also ensure Scheme, distribution of Dhoti, Sector wise the Budget # "# "#%& ' (! # whether the provisions of the Saree, Lungi among masses etc. allocates 26,734.05 crore for ) ! Budget are actually benefitting The Budget also talks about General Sector, 33,625.72 the masses. setting up community food crore for Social Sector and from non-tax revenue, in the growth rate. In compari- which will improve the credit The State Government also centres named after former 30,917.23 crore for Economic 17,891.48 crore from Central son to the decline in national rating of the State. In FY 2021- brought in several schemes and CM and JMM chief Shibu In the field of education sev- plans will be far reaching. -

List of Successful Candidates - Share in Electorate and Voter Turnout

Election Commission Of India - General Elections, 2004 (14th LOK SABHA) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES - SHARE IN ELECTORATE AND VOTER TURNOUT WINNER SHARE IN CONSTITUENCY WINNER NAME SEX & PARTY VOTES TOTAL VOTER POLL Electors Voter AGE POLLED ELECTORS TURNOUT %age Turnout ANDHRA PRADESH 1. SRIKAKULAM YERRANNAIDU KINJARAPUM - 47 TDP - Telugu Desam361906 958626 723948 75.52 37.75% 49.99% 2. PARVATHIPURAM (ST) KISHORE CHANDRA SURYANARAYANA DEO M - 57 INC - Indian National Congress321788 896336 660932 73.74 35.90% 48.69% VYRICHERLA 3. BOBBILI KONDAPALLI PYDITHALLI NAIDU M - 73 TDP - Telugu Desam373922 976012 747072 76.54 38.31% 50.05% 4. VISAKHAPATNAM JANARDHANA REDDY NEDURUMALLIM - 69 INC - Indian National Congress524122 1515574 966128 63.75 34.58% 54.25% 5. BHADRACHALAM (ST) MIDIYAM BABU RAOM - 52 CPM - Communist Party of Indi373148 1193297 823532 69.01 31.27% 45.31% 6. ANAKAPALLI CHALAPATHIRAO PAPPALA M - 58 TDP - Telugu Desam385406 1023113 782106 76.44 37.67% 49.28% 7. KAKINADA MALLIPUDI MANGAPATI PALLAM RAJUM - 41 INC - Indian National Congress410982 1164984 832347 71.45 35.28% 49.38% 8. RAJAHMUNDRY ARUNA KUMAR VUNDAVALLIM - 49 INC - Indian National Congress413927 1074223 816276 75.99 38.53% 50.71% 9. AMALAPURAM (SC) G.V. HARSHA KUMARM - 43 INC - Indian National Congress350346 904207 704415 77.9 38.75% 49.74% 10. NARASAPUR CHEGONDI VENKATA HARIRAMA JOGAIAHM - 67 INC - Indian National Congress402761 996175 768918 77.19 40.43% 52.38% 11. ELURU KAVURU SAMBA SIVA RAOM - 60 INC - Indian National Congress499191 1151672 896961 77.88 43.34% 55.65% 12. MACHILIPATNAM BADIGA RAMAKRISHNAM - 61 INC - Indian National Congress387127 993370 755759 76.08 38.97% 51.22% 13. -

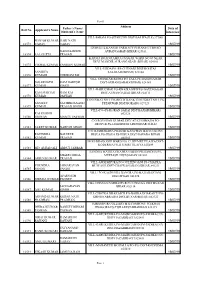

Roll No. Applicant's Name Address 16573 VILL

Sheet1 Address Father’s Name/ Date of Roll No. Applicant’s Name Husband’s Name Interview VILL-PARSIA PO-SITAKUND DIST-BALIYA(U.P) 277001 SHIVAM KUMAR HARI NATH 16573 YADAV YADAV 19/07/19 GURUKUL KANGRI FARMACY PURANI G.T.ROAD NAND KISHOR AURANGABAD BIHAR 824101 16574 LAL GUPTA PRASAD 19/07/19 KARMA ROAD RAMRAJ NAGAR WARD NO 07 NEAR DEVI MANDIR AURANGABAD (BIHAR) 824101 16575 VISHAL KUMAR SANJEEV KUMAR 19/07/19 VILL-URDA PO+PS-CHENARI DIST-ROHTAS SANGITA SASARAM(BIHAR) 821104 16576 KUMARI SHRIRAM PAL 19/07/19 VILL-SHANKAR BIGHA PO-SASA PS-DAUDNAGAR JAGARNATH RAM NARESH DIST-AURANGABAD(BIHAR) 824143 16577 KUMAR SINGH 19/07/19 VILL-HABUCHAK PO-KHAIRADWIP PS-DAUDNAGAR RAM SUBHAG RAM RAJ DIST-AURANGABAD BIHAR 824113 16578 KUMAR PASWAN 19/07/19 TENUGHAT NO 1 PO-RIGHT BANK TENUGHAT NO 1 PS- SANJEEV SACHHIDANAND PETARWAR DIST-BOKARO 829123 16579 KUMAR PRASAD SINGH 19/07/19 VILL+PO+PS-KORAN SARAI DIST-BAXAR(BIHAR) RAJ KISHOR 802126 16580 PASWAN MANTU PASWAN 19/07/19 C/O ROUSHAN KUMAR DEV AT KUSHMAHA PO- DEOPUR PS-JASIDIH DIST-DEOGHAR 814142 16581 SAKET KUMAR NARESH SINGH 19/07/19 C/O RAMRAKSHA PRASAD KANCHAN BAG COLONY RAVINDRA BALVEER HISUA PO-HISUA PS-HISUA DIST-NAVADA BIHAR 16582 KUMAR PRASAD 805103 19/07/19 MOH-BHADODIH WARD NO 17 JHUMRI TILAIYA DIST- KODERMA PO-JHUMRI TILAIYA 825409 16583 MD. AMJAD ALI ABDUL JABBAR 19/07/19 SANDHA MATHIA CHAPRA SARAN PO-SANDHA PS- SHATRUGHNA MUFFASIL DIST-SARAN 841301 16584 ARJUN KUMAR PRASAD 19/07/19 VILL-AWADHPURA PO-GULTENGANJ PS-CHAPRA VIJENDRA JAINARAYAN MUFFASIL DIST-CHAPRA(SARAN) BIHAR 841211 16585