Derivation and Application of a Meat Utility Index for Phocid Seals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unforgiving LAND

the Unforgiving LAND a novel Paul Sullivan Royal Fireworks Press Unionville, New York For Nita, a special person 6 This book is a novel. It is a work of fiction. Names, characters, locations, and events either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or places or events is entirely coincidental. Copyright © 2020, 1996 Royal Fireworks Online Learning, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Royal Fireworks Press P.O. Box 399 41 First Avenue Unionville, NY 10988-0399 (845) 726-4444 fax: (845) 726-3824 email: [email protected] website: rfwp.com ISBN: 978-0-88092-256-2 Publisher: Dr. T.M. Kemnitz Editor: Jennifer Ault Book and Cover Designer: Kerri Ann Ruhl Cover Art: Christopher Tice Printed and bound in Unionville, New York, on acid-free paper using vegetable-based inks at the Royal Fireworks facility. 20my20 local 363 CHAPTER ONE The Promise Inatukk had a vision. It came to him when he was a boy, and if it had not been for this, the people would not have settled to hunt the land and sea ice of the place later known as Hewitt Sound. It was with this vision that it started, and it was because of the vision that it ended as it did. The people came out of the mist of time. They traveled over the harsh, frozen land with their dogs and sleds, carrying all they owned with them. They were hunters, and Inatukk’s father was the greatest and most respected of these. They had not set out for the place deliberately. -

Traditional Foods Poster

LET’S EAT MORE of ALASKA’S TRADITIONAL You can donate hunted and FOODS! gathered foods to food service programs, senior meals, food DONATE THESE: banks, schools, hospitals, etc. • Most wild game meat • Fish Help keep Alaskans • Seafood (excluding molluscan shellfish) healthy by sharing • Marine mammal meat and fat (maktak and seal meat). our local foods • Plants, including fiddlehead and sourdock HOW TO DONATE: • Berries • Mushrooms • Meats: whole, quartered, or roasts • Eggs (whole, intact, and raw) • Fish: gutted and gilled, with or without heads • Plants: whole, fresh or frozen NOT THESE: • Fox, polar bear, bear, and walrus meat • Seal oil or whale oil, with or without meat • Fermented game meat (beaver tail, whale flipper, seal flipper, maktak, and walrus) • Homemade canned or vacuum sealed foods • Smoked or dried seafood products, unless those products are prepared in a seafood processing facility permitted under 18 AAC 34 • Fermented seafood products (salmon eggs, fish heads, and other) • Molluscan shellfish MATION C NAL INFOR AN BE FO DITIO UND AD gov/eh/fss/food/tradition AT: c.alaska. al_food p://de alaska.edu/elde s.htm htt /www.uaa. rs/traditio l / http:/ nalfoo http:/ ds This project was supported, in part by grant number, 90OI0004/03 from the U.S. ACL/Administration on Aging, Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C. 20201. LET’S EAT MORE of ALASKA’S TRADITIONAL ACCEPTING DONATIONS • Meats: whole, quartered, or roasts FOODS! • Fish: gutted and gilled, with or without heads • Plants: whole, fresh or frozen -

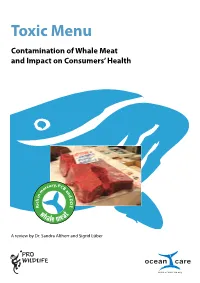

Toxic Menu – Contamination of Whale Meat

Toxic Menu Contamination of Whale Meat and Impact on Consumers’ Health ry, P rcu CB e a m n d n i D h D c i T . R wh at ale me A review by Dr. Sandra Altherr and Sigrid Lüber Baird‘s beaked whale, hunted and consumed in Japan, despite high burdens of PCB and mercury © Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) © 2009, 2012 (2nd edition) Title: Jana Rudnick (Pro Wildlife), Photo from EIA Text: Dr. Sandra Altherr (Pro Wildlife) and Sigrid Lüber (OceanCare) Pro Wildlife OceanCare Kidlerstr. 2, D-81371 Munich, Germany Oberdorfstr. 16, CH-8820 Wädenswil, Switzerland Phone: +49(089)81299-507 Phone: +41 (044) 78066-88 [email protected] [email protected] www.prowildlife.de www.oceancare.org Acknowledgements: The authors want to thank • Claire Bass (World Society for the Protection of Animals, UK) • Sakae Hemmi (Elsa Nature Conservancy, Japan) • Betina Johne (Pro Wildlife, Germany) • Clare Perry (Environmental Investigation Agency, UK) • Annelise Sorg (Canadian Marine Environment Protection Society, Canada) and other persons, who want to remain unnamed, for their helpful contribution of information, comments and photos. - 2 - Toxic Menu — Contamination of Whale Meat and Impact on Consumers’ Health Content 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 2. Contaminants and pathogens in whales ....................................................................................................... -

Putrid Meat and Fish in the Eurasian Middle and Upper Paleolithic: Are We Missing a Key Part of Neanderthal and Modern Human Diet?

Putrid Meat and Fish in the Eurasian Middle and Upper Paleolithic: Are We Missing a Key Part of Neanderthal and Modern Human Diet? JOHN D. SPETH Department of Anthropology, 101 West Hall, 1085 South University Avenue, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1107, USA; [email protected] submitted: 21 February 2017; revised 2 April 2017; accepted 4 April 2017 ABSTRACT This paper begins by exploring the role of fermented and deliberately rotted (putrefied) meat, fish, and fat in the diet of modern hunters and gatherers throughout the arctic and subarctic. These practices partially ‘pre-digest’ the high protein and fat content typical of northern forager diets without the need for cooking, and hence without the need for fire or scarce fuel. Because of the peculiar properties of many bacteria, including various lactic acid bacteria (LAB) which rapidly colonize decomposing meat and fish, these foods can be preserved free of pathogens for weeks or even months and remain safe to eat. In addition, aerobic bacteria in the early stages of putrefaction deplete the supply of oxygen in the tissues, creating an anaerobic environment that retards the production of po- tentially toxic byproducts of lipid autoxidation (rancidity). Moreover, LAB produce B-vitamins, and the anaerobic environment favors the preservation of vitamin C, a critical but scarce micronutrient in heavily meat-based north- ern diets. If such foods are cooked, vitamin C may be depleted or lost entirely, increasing the threat of scurvy. Psy- chological studies indicate that the widespread revulsion shown by many Euroamericans to the sight and smell of putrefied meat is not a universal hard-wired response, but a culturally learned reaction that does not emerge in young children until the age of about five or later, too late to protect the infant from pathogens during the highly vulnerable immediate-post-weaning period. -

Meat Consumption from Stranded Whales and Marine Mammals in New Zealand: Public Health and Other Issues

Meat consumption from stranded whales and marine mammals in New Zealand: Public health and other issues M W Cawthorn Cawthorn & Associates Marine Mammals/Fisheries Consultants 53 Motuhara Road Plimmerton Wellington Published by Department of Conservation Head Office, PO Box 10-420 Wellington, New Zealand This report was commissioned by Hawke's Bay, Wellington and Otago Conservancies ISSN 1171-9834 1997 Department of Conservation, P.O. Box 10-420, Wellington, New Zealand Reference to material in this report should be cited thus: Cawthorn, M.W., 1997 Meat consumption from stranded whales and marine mammals in New Zealand: Public health and other issues. Conservation Advisory Science Notes No. 164, Department of Conservation, Wellington. Keywords: Whales, seals, food preparation (marine mammal), meat quality assessment (marine mammal), flensing, pathogens, contaminants Abstract Interest in the use of stranded whales as a source of food and the use of seals for cultural purposes has been expressed to the Department of Conservation by Ngati Hawea and Ngai Tahu Maori respectively. The known and anecdotal history of consumption of whale and seal meat in New Zealand and elsewhere is briefly discussed. Comments on the palatibility of marine mammal meat and the use of whales and seals as food are presented. Post-stranding damage and carcass contamination result in unsuitability of meat for human consump- tion. Criteria for the assessment of meat quality from stranded animals are presented. The transmission of parasites, particularly Anisakis sp., and the cumulative effects of persistent pesticides and heavy metals from consump- tion of meat from species such as pilot whales is discussed. Meat collection and storage should be conducted under the same conditions and constraints applied to terrestrial mammals. -

Recent Dietary Studies in the Arctic.Pdf

75 Chapter 7 Recent Dietary Studies in the Arctic ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Bente Deutch Summary muskox (Ovibos moschatus), brown bear (U. arctos), black bear (U. americanus), Dall sheep (Ovis canadensis Dietary surveys serve several purposes, namely to de- dalli), and a number of smaller animals are also caught. scribe and analyze the food choice and nutritional ade- Berries, mushrooms, roots, and green plants are also quacy of the diet and to assess the role of food compo- gathered. In addition to their importance as a source of nents as sources/carriers of anthropogenic pollutants, in- nutrition, traditional foods serve as a focus for cultural cluding heavy metals, organochlorine (OC) compounds and social activities and help to maintain the social and radionuclides. Dietary surveys have been performed bonds within societies through the traditional sharing of among Arctic populations as part of the AMAP Human the hunt/harvest and feasting together. Health Programme and as part of independent studies. The indigenous peoples are well aware of the many A very large body of dietary information has been accu- benefits of traditional food systems, and as such these mulated in Canada over the last twenty years, especially form integral parts of their holistic concept of health. by the Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and En- Certain benefits are repeatedly emphasized in surveys re- vironment (CINE). garding attitudes toward traditional foods: well-being, This chapter focuses mainly on recent AMAP-related health, leisure, closeness to nature, spirituality, sharing, dietary studies, in particular where it has been possible community spirit, pride and self-respect, economy, and to make comparisons between different geographic and the education of children (Van Oostdam et al., 1999; ethnic groups. -

Healthy Traditional Alaskan Foods in Food Service Programs

Resources Alaska Food Code: https://dec.alaska.gov/commish/regulations/pdfs/18%20AAC%2031.pdf Department of Fish and Game Transfer of Possession Form: http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/static/regulations/wildliferegulations/pdfs/transfer.pdf Department of Conservation Request for Variance: https://dec.alaska.gov/eh/fss/forms/food/VarianceRequest.pdf Fiddlehead Fern Food Safety: https://dec.alaska.gov/eh/fss/Food/Docs/Fact_Fiddlehead_Food_Safety.pdf Additional information can be found at: http://dec.alaska.gov/eh/fss/food/traditional_foods.html http://www.uaa.alaska.edu/elders/traditionalfoods This project was supported in part by grant number, 90OI0004/03 from the U.S. ACL/Administration on Aging, Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, D.C. 20201. Donating Alaskan Foods to Food Service Programs Community Building Food is a way to bring communities The short answer to the question “Can we serve traditional foods in food together. Donating food to food service programs?” is “Yes!” However, there are still guidelines that must be service providers can create followed in order to comply with regulations. bonds between community members, generations, and There has been much confusion about the ability to serve traditional Alaskan families. Hunting and foraging foods in food service programs. For the purpose of this guide, a food service for local foods is a way to engage program is defined as an institution or nonprofit program that provides meals. youth and Elders and pass on Examples include licensed residential child care facilities, food banks and valuable knowledge about the world pantries, school lunch programs, and senior meal programs. Meals served at around us. -

Veganism As a Virtue: How Compassion and Fairness Show Us What Is Virtuous About Veganism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2017 Veganism as a Virtue: How Compassion and Fairness Show Us What Is Virtuous about Veganism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/202 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Research Paper Future of Food: Journal on Food, Agriculture and Society 5 (2) Autumn 2017 Veganism as a Virtue: How compassion and fairness show us what is virtuous about veganism CARLO ALVARO*1, 1 New York City College of Technology of the City University of New York & St. Francis College, Brooklyn, United States of America * Corresponding author: [email protected] | +1 917-658-1901 Data of the article First received : 20 June 2017 | Last revision received : 07 September 2017 Accepted : 8 September 2017 | Published online : 16 October 2017 URN: nbn:de:hebis: 34-2017072653143 Key words Abstract Veganism, With millions of animals brought into existence and raised for food every year, their negative Virtue Ethics, Compassion, impact upon the environment and the staggering growth in the number of chronic diseases Fairness caused by meat and dairy diets make a global move toward ethical veganism imperative. Typi- cally, utilitarians and deontologists have led this discussion. The purpose of this paper is to pro- pose a virtuous approach to ethical veganism. -

Alaska's Wild Wonders Issue 10, Wild Foods

Alaska's Wild Wonders Wild foods: learn, harvest, share In this Issue: Alaska has an amazing abundance of wild foods. For many people in this state, living is centered around the traditions and practice of wild food harvest. Explore wild foods by ecoregion - or an area defined by the plants and animals that live there. Learn how wild foods are good for our health, and about some ways that Alaskans harvest and share wild foods within families and communities. For Educators: Content Find the ADF&G wildlife-inspired curricula and lots of Why wild foods? . 2 other learning resources online: alaska.gov/go/n4ug Coastal Wetlands . .3 Boreal Forest . 4 Also, visit adfg.alaska.gov and search for Coastal Rainforest . .5 "Wild Wonders" to find vocabulary, activities, Alpine Tundra . 6 and other supporting materials for this issue. NW Coastal Plain . 7 Activity . 8 Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, 2020 What is a wild food, anyway? Wild foods are animals, plants and fungi that are not farmed by people and survive in the wild on their own. Why choose wild foods? 1) They are good for your health! Wild foods do not have chemicals or any other ingredients added by people. Many wild foods have important nutrients like proteins, carbohydrates, healthy fats, vitamins and minerals. 2) Foraging is an outdoor activity. Finding wild food means time spent outside with friends and family, building connections with nature, learning new skills, and time away from screens. 3) Get moving! Whether hiking to hunt small game, fly fishing in a river or traversing the tundra picking berries, foraging often means physical activity and the yummiest rewards for hard work! 4) Become a naturalist: finding and harvesting wild foods requires serious skills like identifying plants, animals, and fungi, and an understanding of the places we live in, rely on, and are a part of. -

Train Oil and Snotters Eating Antarctic Wild Foods

investigations | jeff rubin Train Oil and Snotters Eating Antarctic Wild Foods To a man who is really hungry it is a very subordinate matter ably.” William Elder, principal owner of a New Zealand what he shall eat; the main thing is to have something to whaling company that sent sealing gangs to Macquarie satisfy his hunger. Island in the late nineteenth century, reported that his men “came back heavier than when they went away.”1 —Kristian Prestrud, Norwegian Antarctic Expedition, 1910–12 Shipwrecked seamen survived only by foraging. “When we first landed, our craving for fresh food was such that our Intrepid gourmets are no longer able to sample the narrow strip of shingle beach became unsafe for any living wild foods of Antarctica, as the Antarctic Treaty’s 1991 thing,” wrote F.D. Ommaney after being stranded on the Protocol on Environmental Protection prohibits even “disturbing” any wildlife, except in case of life-threatening emergency. Until relatively recently, however, visitors to Manna from heaven could not Antarctica and the peri-Antarctic islands regularly ate the animals and plants they found there. Penguins and seals, have seemed more delicious naturally, were the most frequently consumed species, than lumps of seal or penguin though a variety of eggs, seabirds, shellfish, and several unusual endemic plants were also eaten. Indeed, there is a meat made into a hash with long history of living off the land in Antarctica and on the remote islands of the Southern Ocean surrounding the a handful of oatmeal. continent, a history we can glean from the diaries, letters, and published accounts of those who spent time there. -

Gifts from Our Relations Indigenous Original Foods Guide National Indigenous Diabetes Association

GIFTS FROM OUR RELATIONS INDIGENOUS ORIGINAL FOODS GUIDE NATIONAL INDIGENOUS DIABETES ASSOCIATION OUR VISION: The National Indigenous Diabetes Association envisions diabetes-free healthy communities. OUR MISSION: The National Indigenous Diabetes Association’s mission is to lead the promotion of healthy environments to prevent and manage diabetes by working together with people, communities and organizations. CONTACT US: 103 - 90 GARRY STREET WINNIPEG, MANITOBA R3C 4H1 PH: 1-877-232-6232 Funding for this guide was provided in part by Indigenous Services Canada. Indigenous Services Le financement de ce guide a été fourni en partie par Services aux Autochtones Canada. Services Canada and the Government of Canada are not responsible for the content and do not necessarily aux Autochtones Canada et le gouvernement du Canada ne sont pas responsables du contenu et ne endorse the views expressed in this document. souscrivent pas nécessairement aux opinions exprimées dans ce document. Published by National Indigenous Diabetes Association. ©2020 CONTENTS 2 Introduction 3 Wild Foods are Healthy Because... 4 Bison 6 Moose 8 Elk 10 White Tailed Deer ABOUT THE NATIONAL 12 Caribou INDIGENOUS DIABETES ASSOCIATION 14 Seal The National Indigenous Diabetes Association envisions diabetes-free healthy communities. As such, our mission is to lead the promotion of 16 Rabbit healthy environments to prevent and manage diabetes by working together with people, communities and organizations. 18 Muskrat This resource takes inspiration from the Traditional Food Fact Sheets 20 Prairie Chicken created by BC First Nations Health Authority (http://www.fnha.ca/ 22 Goose And Duck Documents/Traditional_Food_Fact_Sheets.pdf) that are currently available. 24 Fish 26 Seafood 28 Seaweed 30 Wild Rice 32 Corn 34 Nuts 36 Saskatoon Berries 38 Maple Syrup 38 References 1 INTRODUCTION The National Indigenous Diabetes Association (NIDA) presents this resource spiritually grounded. -

North / Winter

North / Winter Polar Bear Polar bears are very special to Inuit. Polar bear fur is used to make warm clothing, and the meat is an important source of food. There are many stories and legends about “Nanuk”. Ulu Knife The Ulu knife is an important Inuit tool. It is a shell-shaped knife made of flat stone or metal. This sharp knife is used to cut meat, animal hides and for many other purposes. Seal The seal is a very special animal to Inuit. Seal meat is very nutritious and its skin is waterproof. Seal skin can be used to make summer houses and clothing. In the past, seal oil was burned in lamps for light and heat. Snowshoes Snowshoes of many shapes and sizes have been used by Inuit and First Nations for a very long time! These special shoes make it easier to walk on snow and hunt during the long winter months. Igloo Igloos are houses made from blocks of tightly packed snow. There are no trees in the Arctic, so Inuit found their own way to build houses to keep warm and protected from the winter wind. http://www.ainc-inac.gc.ca/arc/lr/ks/index-eng.asp East / Spring Tepee Plains First Nations, such as the Blackfoot and Sioux, built triangular homes called tepees. These shelters could be taken down and moved as bands followed migrating bison herds – their main source of food. Fiddle The fiddle is a very important part of Métis culture. Traditional fiddlers made their instruments from maple wood and birch bark and played them at dances called “jigs”.